Suspecting Esther

Jerusalem and Israel are not mentioned in the opening chapter of Megillat Esther, but there are some parallels between the language used to describe Achashverosh’s feast and the colors and fabrics used in the building of the Tabernacle in the wilderness and the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. A midrash even suggests that Achashverosh uses some plundered Temple vessels in the debauched celebration described at the beginning of Megillat Esther.

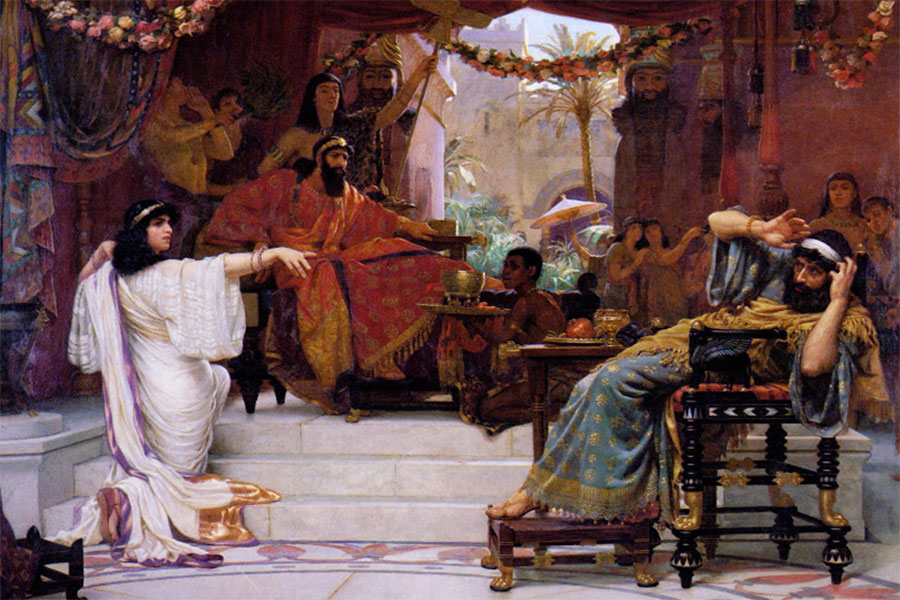

There’s a well-known debate about the dating of Megillat Esther, which centers on whether Achashverosh should be identified with the Persian king Xerxes I (486–465 B.C.E.) or Artaxerxes II (404–358 B.C.E.). If, as most contemporary scholars assume, Achashverosh is supposed to be the first Xerxes, then the events recounted in the Megillah take place only 30 years after the dedication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. That is, Mordechai and Esther must have been among those who had been invited by Cyrus’s proclamation to return to Israel after years of exile and nevertheless remained in Shushan. For Seymour Epstein, this is an invitation to read every single event in the Megillah under a cloud of suspicion, turning the original Purim celebrated at the end of the Megillah into a “tainted victory celebration.”

It’s an interesting, audacious exercise in interpretation against the grain. In Epstein’s reading, every moment of triumph in the Megillah becomes a further indictment of the diaspora. Epstein laments that Mordechai allows Esther to be ravaged by a non-Jewish king instead of protecting his niece and her Jewish identity. Esther, too, is criticized her failure to independently discern the seriousness of the verdict against the Jews while sequestered in the King’s harem, and consequently for failing to stand up for her people herself in the face of adversity. Indeed, Epstein reads the entire book as a denunciation of the inevitable moral and spiritual compromises required by life in the diaspora. Thus, he does not read the text as exulting over the defensive war fought by the Jews against their remaining enemies at the end of the Megillah or even the public hanging of Haman’s sons. For Epstein, the Megillah depicts the cycle of passivity and overreaction that is endemic to the diaspora.

Toward the end of the Megillah, there is an intriguing moment when Haman’s wife and advisors intuit the end: “If Mordecai, before whom you have begun to fall, is of Jewish stock, you will not overcome him; you will fall before him to your ruin” (Esther 6:13). It is not foreign to the Bible for an enemy of the Jews to ultimately recognize their special, chosen status. “How goodly are your tents, O Jacob,” the sorcerer Balaam finds himself saying as he tries to curse Israel. Despite such biblical precedents, however, Epstein cannot but read Zeresh and Haman’s advisers’ prediction cynically: “The author introduces yet another strange aspect of anti-Semitism found in various Diasporas. Genius or magic is ascribed to the Jewish race as a whole as yet another characteristic to fear.” This interpretation, although novel, will strike most sensitive readers of the Bible as simply wrong.

Indeed, as a sweeping theory that purports to radically reread a canonical Jewish text that has been pored over, savored, and brilliantly interpreted over centuries, Epstein’s theory is bound to fall somewhat short. Yet his overarching argument that Esther is underappreciated as a work that criticizes, rather than simply depicts, Jewish life in the diaspora is worth taking seriously.

Zionist interpretations of the Book of Esther open up readings of the book that are easily overlooked in the fun and whimsy of our carnivalesque celebrations of Purim. Such readings invite us not only to celebrate the triumphs of Mordechai and Esther but to question the limits of Jewish life in the diaspora.

For example, in 2:10, we learn that Esther, upon entering Achashveirosh’s palace, does not reveal her Jewish identity because Mordechai warns her to conceal it. Soon afterward, in the third chapter, Mordechai refuses to bow to Haman, explaining to the king’s baffled courtiers that he refuses because he is a Jew. In his book The Dawn, Yoram Hazony points to this moment as a moral turning point where Mordechai goes from a Joseph-like leader who seeks to accommodate himself to a gentile crown to an Abrahamic figure who bravely stands up to his surrounding culture. Epstein is unimpressed. The fact that Mordechai tells Esther to be quiet while he himself reveals his Jewish identity is a matter neither of cunning political strategy nor moral transformation and development but rather “of the confused values Jews beget in the Diaspora.” Epstein suggests that even refusing to bow to Haman is an act of assimilation on Mordechai’s part as “there is no real prohibition of this sort in biblical religion and, if anything, Mordekhai here represents a strong Greek aversion to bowing down in the Persian fashion, one of the many objections the Greek held against Persian culture.” Here and elsewhere, Epstein suggests that the Rabbis “did not get the joke,” mistaking ironic description for the depiction of genuine bravery. Yet one wonders if Epstein, in turning Mordechai into a Greek wannabe who would have been better off bowing to Haman if he really cared about the Jewish people, is missing something crucial as well.

At the close of his commentary, Epstein says that his book is a “product of a post-modern perspective” that is meant to exist among many others. He can’t help but read the book of Esther with the triumphs of 1948 in mind. Once we are cognizant of the immense political and cultural opportunities afforded by the existence of the modern Jewish state, it is certainly tempting to denigrate the scheming of Mordechai and Esther to save their people in circumstances where they lacked sovereign power.

Yet a famous midrash in Yalkut Shimoni writes that in the Messianic era, all Jewish holidays will be nullified except for Purim, and then it adds Yom Kippur to the shortlist as well. Another tradition subordinates Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, to even hold a secondary status to Purim as it is merely Yom “Ki” Purim, or a day that is “like” Purim. This is a rabbinic pun, but it’s also, at some level, serious. Perhaps the rabbis understood that, in a Messianic era characterized by an overwhelming sense of security and spiritual well-being, we will lack the sort of heroic potential that is only possible in an environment where redemption is distant. The diaspora of the Megillah, in which God seems to have been replaced by a capricious tyrant, is the ultimate description of that reality.

Who are we kidding, writes Epstein; diaspora life is a joke when we consider the depth and integrity of Jewish life under independent political sovereignty. It is hard to disagree entirely. But perhaps one needs to experience the darkness of Shushan to grasp the infinite reach of divine providence. In their subtle appreciation of the Megillah and the enduring significance of Purim, perhaps the Rabbis have the last laugh.

Suggested Reading

18 Questions with Jeremy Dauber: The Purim Edition

Who ruled the Borscht Belt: Allan Sherman or Lenny Bruce? Jewish comedy expert Jeremy Dauber casts his vote in a humorous interview—just in time for Purim.

Black Fire on White Fire

The scroll, which was originally a secular technology, became closely associated with Judaism at a time when Christians were adopting the codex for their holy books.

The Bible Scholar Who Didn’t Know Hebrew

The surprising story of Elias Bickerman and his scholarship.

Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In