“Whoever Is Hungry, Come and Eat”? From the Babylonian Poor to the Ashkenazi Elijah

Why do we begin the seder by inviting “whoever is hungry” to come and eat? Aren’t the guests already at the table? And why do we do it in Aramaic? It has something to do with Babylonian magic bowls . . .

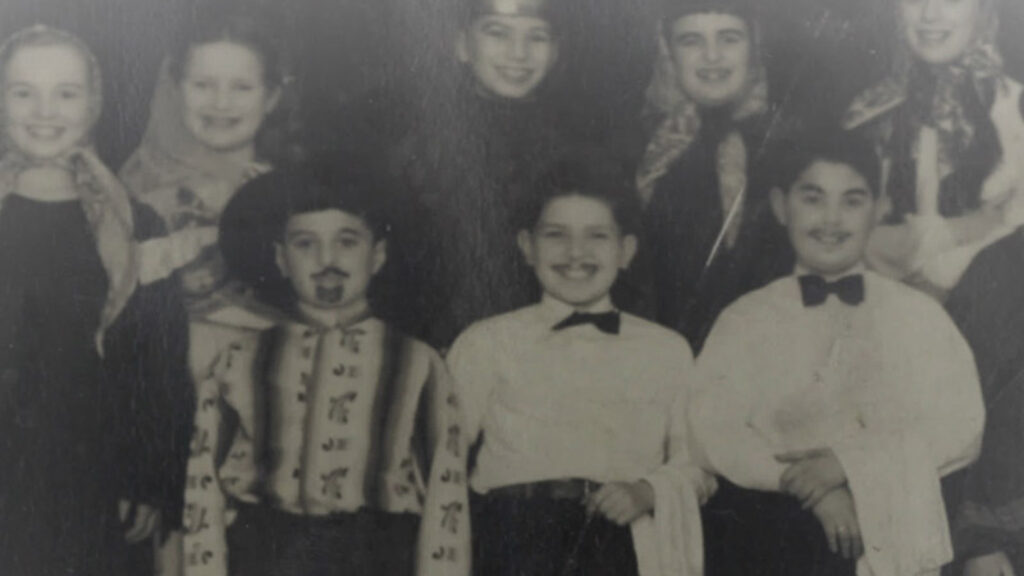

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

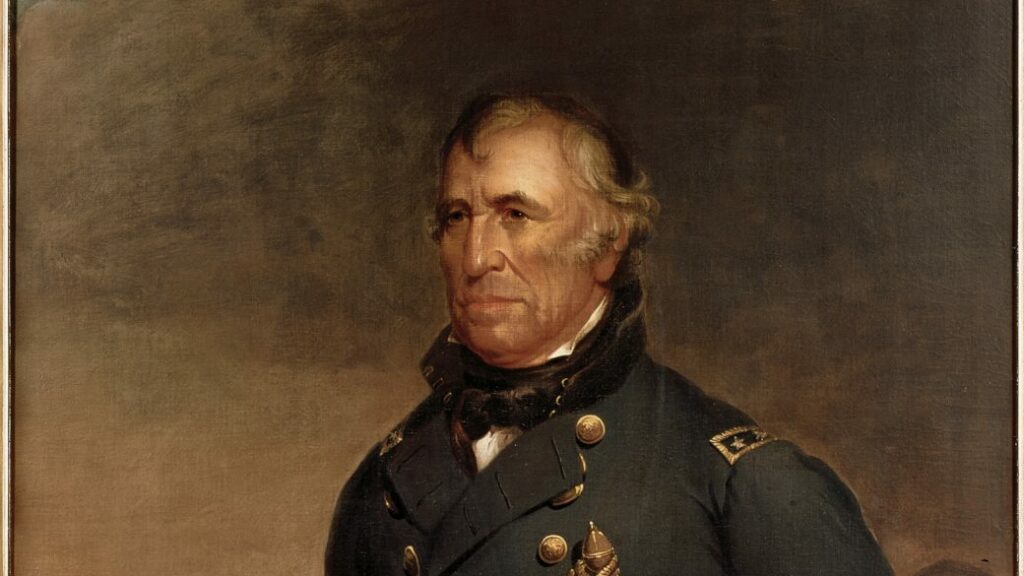

Of Presidents, Rabbis, and Pews

Isaac Mayer Wise was the first Rabbi to meet with an American President. The conversation made Wise a celebrity, it also led to him getting punched in his synagogue, losing his job, and changing the way Reform Jews prayed.

Lechaim!

Back in the 1960s, the Rheingold Corporation ran a bunch of TV commercials—mostly during baseball games, if I remember correctly—vaunting the popularity of its beer among all sorts of minority…

Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and what does their success have to do with the future of Modern Orthodoxy?

He Shall Not Press His Fellow

Once every seven years, the Torah says, the economic playing field should be leveled, and those trapped in debt should be freed. Even the rabbinic workaround reminds us of the ideal–as I was reminded after my startup foundered in the 2008 financial crisis.

Hasidism, Jung, and the Jewish Spiritual Crisis

Carl Jung said that the great “the Hasidic Rabbi whom they called the Great Maggid” anticipated his entire psychology. He learned that from his Jewish student Erich Neumann, whose Roots of Jewish Consciousness was never published until now.

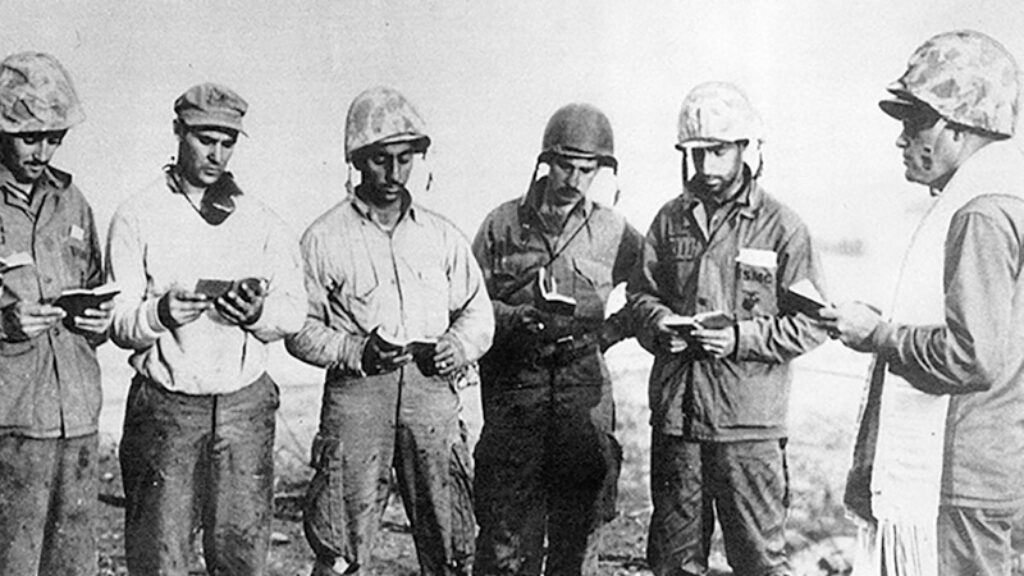

This Shall Not Be in Vain

Rabbi Roland B. Gitelsohn was a pacifist when World War II started. Four years later he was chaplain at the Battle of Iwo Jima. His long-lost memoir has just been published.

Mansions, Museums, and Magen Davids

In building (or rebuilding) grand houses in France and England Jewish immigrants created, brick by brick, edifices within their countries’ histories. Not all would survive World War II.

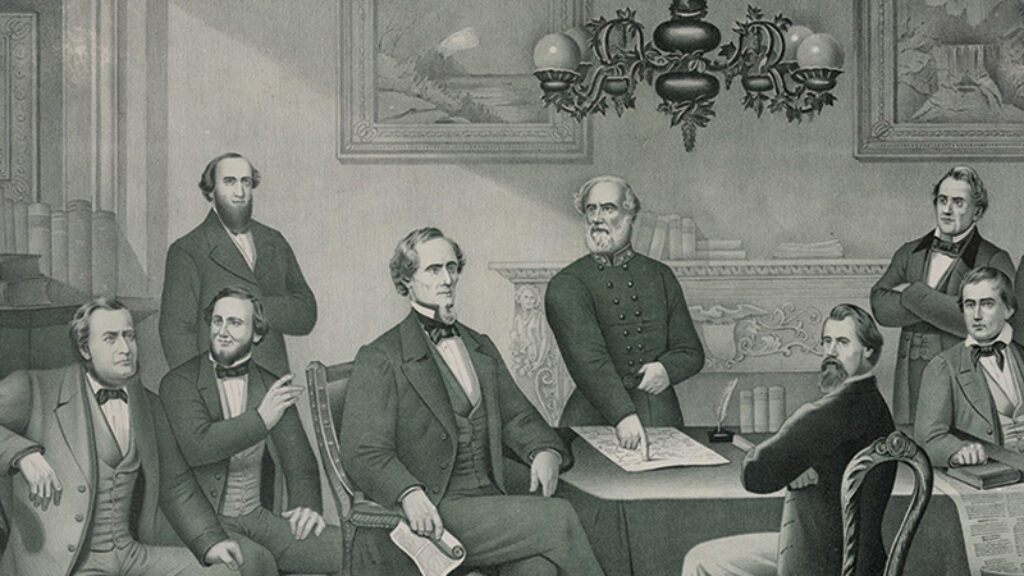

An Israelite with Egyptian Principles

Judah Benjamin was a brilliant New Orleans lawyer who became the most important cabinet member in Jefferson Davis’s Confederate government. He was, Senator Benjamin Wade correctly declared, one of the “Israelites with Egyptian principles.”