The Improbables

“Write what you know” is dangerous advice. The writer who takes it risks solipsism, dullness, a lack of perspective, or all three. It is refreshing, then, to see Molly Antopol steer away from the autobiographical shoals in The UnAmericans, a collection of short stories for which she received the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 award. This young American author tells the stories of lovers past their prime, Czech dissidents, postwar American Communists, teenage partisans, and Israeli soldiers.

Witty descriptions and engaging characters are among Antopol’s strengths. In “A Difficult Phase,” a young Israeli journalist makes some sullenly funny observations:

“I have a job,” Talia said, and when both her parents said, “Journalism?” they laughed, as if she was five years old and had just announced that when she grew up she wanted to be a robot, or a dragon.

In the same story, Antopol perfectly depicts a 20-something worldview: “That was how people grew to be unhappy, she thought—by not making choices, by just letting what was warm and wonderful in one moment dictate the next, until one day they were living a life completely unsuited to their dreams.” Talia does not yet know how simplistic she is being, but Antopol does, and she shows us this with writerly wisdom, forgoing exaggeration or mockery.

Her book is careful with its language, and frequently its emotions, but only intermittently with its history. Suffice it to say that the large, ancient, sophisticated city of Kiev would not have boasted a village beauty and that torches were not necessary for navigating its streets in the 19th or 20th centuries. And yet, that is how the narrator of the collection’s first story, “The Old World,” describes Kiev in his grandfather’s day. The Jews of Kiev spoke Russian and sometimes Yiddish, but hardly ever, as Antopol seems to think, Ukrainian (a language banned by both czarist and Soviet regimes). And yet, the Israeli protagonist of “A Difficult Phase” learned Ukrainian from her Kievan grandparents, but Russian only at university.

Interrogations in Soviet-era Czechoslovakia were more likely to include beatings than beef dinners (rare enough for ordinary civilians), but that is what the dissident in “The Quietest Man” continues to be served, even as he refuses to talk. Contrary to the breezy generalizations in the final story, “Retrospective,” Soviet dissident artists did not typically paint with mud, trash, and “anything they could scavenge off the streets,” but with paint, and burying subversive messages within official-seeming artwork was not an act of rare bravery, as Antopol suggests, but common practice. In “My Grandmother Tells Me This Story,” Jewish partisans board a train, kill soldiers, and then loudly, repeatedly, purposefully announce their Jewishness to the passengers. This would have certainly led to terrible reprisals against other Jews; is it really likely that exuberance and pride would have overcome this awareness?

Although it is possible to look past or explain away some of these improbabilities, certain patterns begin to emerge. Eastern European countries and their residents appear more backward, oppression is less oppressive, and heroes are less heroic than history suggests. Several stories seem to have been built upon the same framework: We meet people generally considered to have been paragons and watch them topple from their pedestals. As they pile up, such narrative reversals lose the power to surprise.

Does any of this matter? As Virginia Woolf said, “Art is not a copy of the real world; one of the damn things is enough.” But there is a difference between fabricating deliberately, in service of a greater truth, and fabricating unconsciously, out of complacency.

The improbabilities, while dissonant with the times and places Antopol mentions, are not unfamiliar. The misplaced images of Kiev seem to emerge from some reservoir of shtetl lore, possibly from the writing of any number of other American Jewish authors about “the old world.”

It is difficult to lose oneself in a world that seems flimsy and second-hand. The reader transforms into an unwilling fact-checker, questioning everything; trust erodes. I know less about Israel and California than I do about the former Soviet Union, but still found myself pulled up short again and again—yanked out of the narrative and into Wikipedia. (Wouldn’t the use of the idiom “ahead of the curve” in the mid-century world of “The Unknown Soldier” be, well, ahead of the curve, as the earliest instances of that idiom seem to have occurred in the 1970s?) Perhaps more importantly, the relatively small untruths in this book interfere with its ability to tell larger truths about characters. The Kievan girlfriend in “The Old World” is melancholic, mysterious, calls the narrator her “big bear,” cries often; these resemblances to stereotypes about Eastern European women strip her of some of her individuality.

In “The Quietest Man,” Tómas—the object of the unusually gentle interrogation—conforms to type in a different, but equally problematic way. Who is Tómas? A man who does not betray his friends and is lionized for his loyalty. But also—and, to the story, more importantly—a lousy father, similar to the self-involved, unsupportive dads we find in Richard Ford and Jennifer Weiner. Very little about this man’s character finds root in his prior experiences, which, while unrealistically mild, still include the arrests of his friends, the loss of his language, the severance of his former life. Tómas’ ease in the world, his entitlement, his general lack of trouble with his past, suggest a youth spent in suburban New Jersey, not a police state.

As an American father, such a character would have been believable, if not strikingly original; as Antopol describes him, he is confusing, but not interesting. It feels as though someone grafted a somewhat exotic Eastern European biography onto a familiar prototype. Perhaps this odd choice marks an attempt to humanize a “heroic” character. But is this the right decision? When writing about someone seemingly larger than life, an author can either stretch her imagination to understand, or shrink a character into more comfortable, but less true, dimensions. Counterfactuals present their own issues, but a reader can’t help wondering how a story that took on more likely—and difficult—circumstances might have turned out. Had Tómas survived a typical interrogation, he may well have been an inadequate father, but of an utterly different (and more compelling) kind.

Vagueness about history and its horrors suffuses and ultimately undermines too many of these stories. Child partisans operate in “Europe”—not any particular country—and kill “soldiers.” Whether the soldiers were German nationals or collaborators would have determined the size of the reprisals, and thus would have been important to the partisans. The grandfather who emigrated from Kiev does not seem to have ever mentioned, in any of the endless stories he apparently told the narrator of “The Old World,” the period during which he emigrated. This “detail” would have figured in his story of escape and, indeed, would have been crucial to it. The fates of the dissident artists whose work a benefactress smuggled abroad in “Retrospective” are never mentioned—were any of them caught and punished for this “collaboration with the West”? In “The Quietest Man,” Tómas is similarly unconcerned with the fates of the dissidents he left behind.

How did the grandparents in the otherwise very good story “A Difficult Phase” manage to leave Kiev? Antopol refers to their “work[ing] so hard to leave”—but that would have been the least of it, if the emigration took place during the early or mid-Soviet era, as it seems to have (but again, the story leaves this essential detail vague). Those who are or were bound by history are unlikely to share Antopol’s somewhat casual attitude toward it. The information she omits or elides is not the irrelevant background she seems to think it is; it’s an essential portion of her characters’ lives, or at any rate, of the kind of real people her characters are meant to depict.

When writing what we don’t know, we can use anything that seems useful. Certainly, family stories (which the author cites as an influence) can spark imagination and help us empathize with characters unlike ourselves. However, empathy is not the same thing as understanding. At some point, it becomes important to ask whether a particular idea represents an intuition or a stereotype, to look critically at those wonderful but often less than reliable family stories, to examine a wide range of resources, and ultimately to carve out a solid understanding, while recognizing that it is necessarily incomplete. This is hard, but not impossible. Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty, for instance, is the best English-language novel about Khrushchev-era economic policy you’ll ever read. But then, Spufford was deeply interested in that time and place.

Nonetheless, there are parts of the collection I greatly enjoyed. Antopol offers sharp observations about relationships—especially when those relationships occur at some remove from dramatic historical events—and truthful insights into young adulthood. In “Retrospective,” after dispatching with her odd notions about dissident art, she gives a sensitive portrait of loneliness:

And the thing about being alone is knowing that if you want to enter the world again, you have to be a guest in it—people are doing you a favor by inviting you into their homes for family gatherings and national holidays, and the only way to act is cheerful and easy, even when you’re so depressed you can barely muster the energy to brush your teeth, and to arrive with wine and flowers and always offer to help with the dishes.

I am not sure why the artists, whom Antopol understands much less well than she does this unhappy young man, had to come into the story at all. In a recent essay in the London Review of Books, Elif Batuman blames MFA programs for contemporary authors’ tendency to unnecessarily pad the personal with the historical, and that seems to be what, all too often, has happened here. Antopol is undeniably talented, but I was left wondering whether that talent would have been better served had she written more of what she knew and cared about.

Suggested Reading

At Home in America

Just beneath the surface of this Holocaust memoir is, in fact, an altogether different tale: a paean to the good life in America.

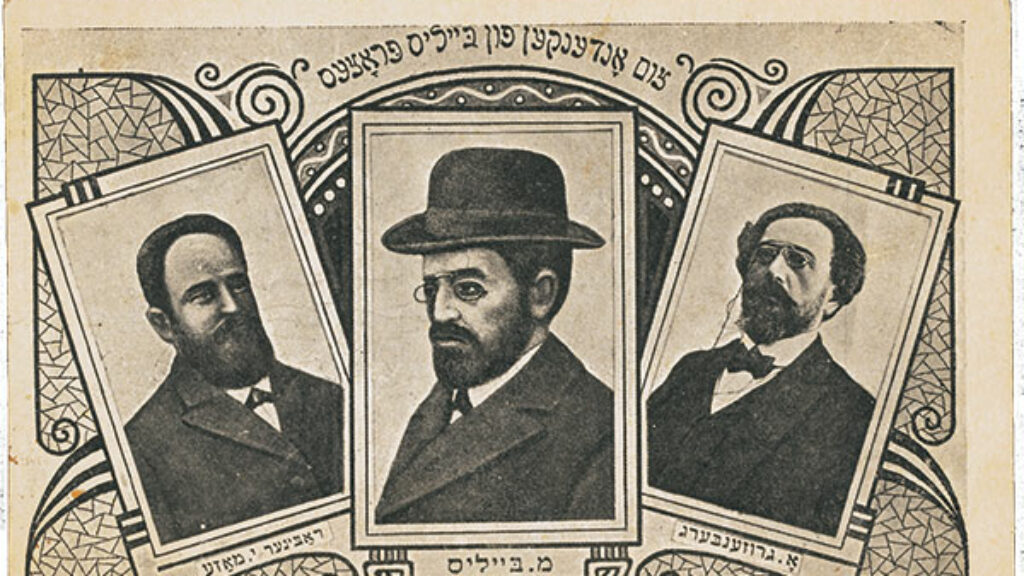

The Mortara Affair, Redux

Bologna, 1857: A six-year old is taken from his Jewish family to be raised a Catholic. Why are we still talking about this case? An archbishop responds.

With Interest

Have the Jews been capitalism's best friends or worst enemies, or both?

Blood Delusion

While the blood libel was rooted in Christianity, it also accused Jews of practicing precisely the opposite of what Judaism itself teaches, namely, not to consume blood.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In