The Many Dybbuks of Romain Gary

Some time ago, a French friend invited me to an event at the Institut Français de Jérusalem, a cultural center tucked into a corridor leading from city hall to the Old City. I noticed the place was named for Romain Gary. “Who’s that?” I asked. “A heroic bullshit artist,” my host replied, promptly turning to grab a glass of Beaujolais nouveau.

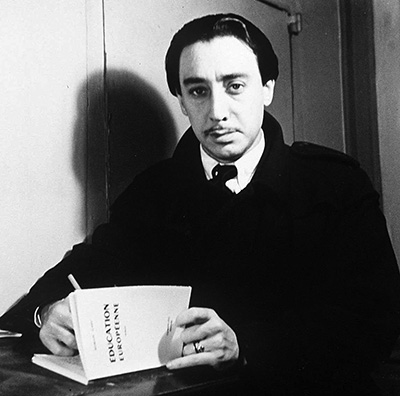

Not long after, I picked up a copy of Gary’s hybrid memoir-novel, Promise at Dawn (1960), republished by New Directions this fall to accompany the first English translation of Gary’s last novel, The Kites. The introspective tone of Promise at Dawn is one of disarming sincerity. It is a stirring picaresque tale, eventually made into a Broadway play, a film in 1970, and again in 2017, starring Pierre Niney as Romain and Charlotte Gainsbourg as his mother.

Yet Promise at Dawn also displays a splendid indifference to facts and a rare talent for self-aggrandizing embellishment. Gary—a Lithuanian Jew who regarded himself a Frenchman par excellence—emerges in the memoir as a master of self-invention and (just as immoderate) verbal invention, a chameleon of pseudonyms, a man of irreconcilable contradictions, divided against himself, though none of this precludes sincerity. The philosopher Harry Frankfurt has said that our own natures are “notoriously less stable and less inherent than the natures of other things. And insofar as this is the case, sincerity itself is bullshit.”

The unembellished facts are exceptional enough. Roman Kacew (pronounced “Katzev”) was born in Vilna in 1914, a few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War, to Mina and Arieh-Leib Kacew. The father (whom Gary would later pretend was of Mongol or Cossack descent) abandoned his wife and child when Roman was 10. Mina, Gary said, besides expecting greatness for her only son, was “affected by an illness quite common in Europe at the time . . . galloping Francophilia, a Joan-of-Arcism typical of Eastern European Jews in particular.” After an impoverished childhood in Vilna and Warsaw, Gary immigrated to France with his mother at age 14. Naturalized as a French citizen in 1935, at age 21, Roman took the name Romain Gary. “Gari in Russian means ‘burn!’” he said in a book-length interview in 1974. “I want to test myself, a trial by fire, so that my I is burned off.”

When France fell to German forces in June 1940, Gary fled to Britain via Algiers, Casablanca, and Gibraltar. He swore allegiance to Charles de Gaulle and spent the war as an airman in the Free French Air Force. Stationed in Central Africa, Egypt, Syria, and England, he flew 26 combat missions, many of them low-level bombing or “hedge-hopping” runs over occupied France. Of the original two hundred aviators of the Lorraine Squadron, as his group was called, only Gary and a handful of others survived the war. For his bravery he was recognized as a Compagnon de la Libération (a title bestowed on resistance fighters for exemplary conduct) and was decorated with the Croix de Guerre.

Gary became entranced by the figure of de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, whom he met several times. “He was a fantastically clever and gifted impersonator of ten centuries of French history,” Gary said. According to Gary’s biographer David Bellos:

De Gaulle became Gary’s best excuse for his own approach to the relationship between dream and reality, imagination and achievement, truth and showmanship. . . . The towering figure of Charles de Gaulle dominated Gary’s view of what it meant to be a great man, that is to say: a myth.

If de Gaulle’s myth was singular, Gary’s would be multiple. In the decade and a half after the war, the heroic aviator married an English novelist and popular historian named Lesley Blanch and turned himself into a diplomat, posted to Sofia, New York (as spokesman for the French delegation at the United Nations), and Los Angeles (as the French consul general).

In December 1959, Gary met the American actress Jean Seberg, the star of Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. He divorced Blanch, married Seberg, and inhabited, with brio, his next role: Hollywood celebrity spouse and film-maker.

Gary co-wrote the screenplay for The Longest Day (1962), a big-budget motion picture about D-Day, starring seemingly everyone from Paul Anka to John Wayne. He wrote and directed two films—Birds in Peru (1968, rated X) and Kill! (1971)—both starring Seberg. Peter Ustinov made a film version of Gary’s novel Lady L., starring Sophia Loren and Paul Newman (1965). Israeli director Moshe Mizrahi made Gary’s best-seller The Life Before Us into an Oscar-winning movie called Madame Rosa (1977). And still Gary’s frenetic ambition was not sated.

He would write 27 books (six of them in English, his sixth language after Yiddish, Russian, Polish, French, and German). Burdened by an excess of memory, by the strain of writing humanely after the wartime inhumanities, Gary tried on and cast off a series of pseudonyms and personas—in retrospect they look like a series of suicides and rebirths. He published as Shatan Bogat (Russian for “rich devil”); John Markham Beach (the fictional translator into English of Promise at Dawn); Fosco Sinibaldi; François Mermont; and most famously Émile Ajar. By means of an elaborate hoax, he became the only writer to win the prestigious Prix Goncourt twice—first in 1956 for his novel set in Africa, The Roots of Heaven, and 19 years later, as Émile Ajar, for The Life Before Us—though the rules of the prize permit an author to receive it only once.

The postwar French literary establishment resented Gary’s fame and commercial success, and more often than not dismissed him as a middlebrow. One did not read Gary’s novels, a critic said. “One would not have been seen dead reading them. Nobody read them. Except, of course, the public.” “The avant-garde are people who don’t exactly know where they want to go,” Gary answered in one of his bon mots, “but are the first to get there.”

Until the mid-1970s, Left Bank intellectuals’ political engagements (including on behalf of Stalin and Mao) camouflaged a lack of engagement with history, a turning away from the painful—and shameful—memories of the recent French past. (Even Gary’s friend Albert Camus, who went farther than most in this respect, depicted the pestilence in The Plague as biological, not ethical in origin.) Gary, by contrast, put that past at the heart of his work. He set store in the old-fashioned humanist view that literature could contribute “to human enlightenment and progress” (as he wrote in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar). As such, Gary refused to play the part of the “engaged” writer in the style of Sartre:

I have been so overexposed to history since my early teens that the very idea of signing a manifesto, of making another purely verbal protest, denouncing another intolerable social situation just to relieve my conscience and to feel better, to feel a fine human being, fills me with shame. I cannot resist human suffering: I fill my books with it.

In his book Hope and Memory: Lessons from the Twentieth Century (2000), the Bulgarian French writer Tzvetan Todorov commends a group of humanists who resisted the dehumanizations of the 20th century. They included Vassily Grossman, Primo Levi, and Romain Gary. In his chapter on Gary, Todorov praises the way Gary’s novels, unclouded by ideological intention and unflinching in the face of suffering, radiate colors at once “tragic” and “vibrant with joy and life.”

Nowhere is Todorov’s praise truer than in Gary’s last novel, now appearing for the first time in English in the superb translation of Miranda Richmond Mouillot. The Kites (originally published in 1980 as Les Cerfs-Volants) is a nuanced coming-of-age story set in a Europe on the road to ruin. Gary dedicated it “To Memory.” Though the book is set in the dark days of German-occupied France, it is cast in language, as Mouillot says, “as soaring and amusing and beautifully whimsical as the kites for which it was named.”

The narrator, Ludo, orphaned by his Catholic parents, is 14 years old when the novel opens in the 1930s. He lives with his uncle, the eccentric pacifist and kite maker Ambrose Fleury, in the town of Cléry in the French countryside in Normandy, near the Channel coast. The boy admires his uncle’s whimsical creations, bobbing and fluttering above the woodlands. Some are animals: a fish “that wiggled its silvery scales and pink fins in the air,” dragonflies with iridescent wings, creatures with flapping paunches and wings shaped like ears. Other kites are figures out of French history: a Victor Hugo, a Montaigne, a Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a Joan of Arc with doves bearing her heavenward.

Like his uncle, Ludo suffers from “an excess of memory.” Both lack the ability to forget. This puts Ludo in good stead when the outbreak of the Second World War severs him from the object of his desire, the fanciful, self-absorbed Lila—a daughter of Polish nobility who suffers from a different kind of excess: “an excess of herself.” (Ludo’s name, one notes, comes from the Latin word for spontaneous play; Lila means the same in Sanskrit.)

For the duration of the war Ludo must live entirely in his memories of Lila, who becomes for him “so present that mentioning her would only have pushed her away.” At last, Ludo burns down the manor where he had met Lila. “Why did you set fire to the place?” Ambrose asks. “To keep it intact,” Ludo replies.

The young man gives the same reply to the defeat and humiliation of France: Occupied France must be sabotaged if the true, remembered France is to remain intact enough to someday recover. Ludo had been wholly unprepared for French defeat. “Mandatory public education had simply taught me too well that liberty, dignity, and human rights were unassailable so long as our nation remained faithful to itself.” Yet in the effort to salvage grace from disgrace, he learns “that other Frenchmen were beginning to live as I did from memory.”

To hasten Lila’s return (and the return of France itself), Ludo joins the underground Resistance. He hides messages in his uncle’s kites, passes on locations of German coastal batteries, coordinates safe houses and escape routes for downed Allied pilots, hides weapons caches under manure pits, and couriers improvised explosive devices disguised as goat cheeses. Above all, he ignores the voices whispering that “France was done for” and that the country had “lost its soul.”

By the same token, Ludo refuses “the routine of reducing Germany to its crimes and France to its heroes.” No cliché, he insists, was more convenient in obscuring a fundamental fact of wartime: “The Nazis were human. And what was human about them was their inhumanity.”

In the summer of 1942, Ambrose is appalled by the inhumanity of the infamous Vel’ d’Hiv round-up of French Jews, including more than four thousand children. Driven to desperation, he dramatically launches yellow kites in the form of Jewish stars:

My uncle Ambrose stood in the meadow in front of the house, surrounded by a few kids from Clos. His eyes were raised to the sky, at those seven stars of shame floating there. Jaws tightened, brow furrowed, his hardened face clenched between his gray crew cut and his mustache, the old man looked like a figurehead that had lost its ship.

On the heels of this defiant act, Ambrose flees to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a town in south-eastern France. He has heard that André Trocmé, the town’s Protestant pastor, together with his wife, Magda, are sheltering hundreds of Jewish children, saving them from deportation. Ambrose aids in this effort until he is himself deported to Buchenwald:

It so happened that one of the camp guards had spent a year stationed with the Occupation forces in the Cléry area and remembered Ambrose Fleury’s kites. . . . The camp commander, with the idea of using inmate labor, had supplied him the necessary materials. My uncle was ordered to go to work. At first, the SS officers brought the kites home as presents for their children or their friends’ children, and then came up with the idea of turning it into a business. My uncle ended up with an entire team of assistants. And thus, floating above the shameful camp, it was possible to see bouquets of kites whose gay colors seemed to proclaim the inextinguishable hope and faith of Ambrose Fleury.

Ambrose’s luck however was not inextinguishable. Ilse Koch, the commandant’s infamous wife, asks him to make for her a kite of human skin. His refusal earns him a trip to Auschwitz.

Ambrose’s final words to his nephew before leaving Cléry had been: “She’ll be back. There will be a lot to forgive her.” “I couldn’t tell whether he was talking about Lila or France,” Ludo says.

As D-Day approaches, Lila at last returns. Having had to sleep with German occupiers to survive, she’s stigmatized as a “fallen woman.” The town barber shaves her head before a jeering crowd. Six weeks later, on the morning of their wedding, Ludo and Lila return to the barber. “I would like you to cut my hair in the latest style again,” Lila announces with a smile. “Like last time.” The barber goes pale. “It wasn’t my idea, I swear to you! They came to get me and . . .” Ludo insists: “We’re not here to talk about whether it was ‘them,’ ‘me,’ ‘I,’ ‘their guys,’ or ‘our guys,’ old pal. It’s always us. Come on. Go ahead.”

Shortly afterward, Gary brings the novel to an abrupt end with an act of memory, an intrusion of fact into fiction. The last lines of Gary’s last novel read: “I end this story by writing . . . the names of Pastor André Trocmé and Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Because there isn’t anything better to say than that.” (Yad Vashem recognized the Trocmés as “Righteous Among the Nations.”)

In December 1980, shortly after he had published The Kites and just more than a year after his ex-wife Jean Seberg had been found dead, probably by suicide, Gary thrust his Smith & Wesson revolver into his mouth and took his own life. He was 66 years old. In his suicide note, Gary quoted the last line of The Kites and signed off: “I have at last said all that I have to say.” The trial by fire had consumed his last I.

According to Gary’s lover (and later biographer) Myriam Anissimov, “he told me that when he wrote about Jewish subjects, his books were always failures.” Certainly he was ambivalent about his Jewish patrimony. Yet in the decades after his death, some critics (notably Jeffrey Mehlman and David Bellos) have read Gary’s fiction as an attempt to come to terms with the memory of French complicity in the deportation and extermination of the country’s Jews.

Gary’s “Holocaust comedy” The Dance of Genghis Cohn (1967) can support both arguments. Among other things, it is an attempt to incorporate the Shoah into the tradition of Jewish legends. A half-Mongol and half-Jewish cabaret comedian is deported to Auschwitz. Made to stand naked on the edge of a mass grave, Genghis Cohn thrusts his bare bottom at the SS firing squad and shouts, in Yiddish, “Kush mir in tokhes!” (Cohn’s ghost confesses: “There have undoubtedly been more worthy and noble last words in history than ‘Kiss my ass,’ but I have never made any claim to greatness and, besides, I’m quite pleased with my effort.”)

The moment the bullets pierce Cohn, his dybbuk permanently embeds itself in his murderer’s soul. To the bewilderment of his colleagues, even two decades later the possessed ex-Nazi finds himself singing Yiddishe Mame and reciting Kaddish on his knees. Unlike The Kites and Promise at Dawn, it would be hard to make a purely literary case for The Dance of Genghis Cohn, though Gary did write to the New York Times to accuse Thomas Pynchon of stealing Gary’s joke name for his own character Genghis Cohen in The Crying of Lot 49. (Pynchon’s response: “I took the name Genghis Cohen from the name of Genghis Khan (1162–1227), the well-known Mongol warrior and statesman. If Mr. Gary really believes himself to be the only writer at present able to arrive at a play on words this trivial, that is another problem entirely, perhaps more psychiatric than literary, and I certainly hope he works it out.”)

Romain Gary’s work, like his life, was by no means all of a piece. Perhaps in the end the writer and the writing alike are best seen not so much under the aspect of bullshit as under the category of protean multiplicity. Perhaps Gary was possessed by a multitude of self-invented, defiantly hopeful dybbuks. Through a distinguished diplomatic career, two marriages, more than two dozen books, and a handful of films, he served as a ventriloquist to them all.

Not long before his death, in a radio interview devoted to The Kites, Gary said: “I don’t always manage to apply to my life the precepts of my books, but this whole book is the story of people who don’t know how to despair.” In that novel, Gary writes of Ambrose the kite maker: “even the final pieces he made in his old age bear that stamp of innocence and that freshness of soul.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hashtag Holocaust

Memorials remain, unmoved and unchanged, by the inevitable erosion of memory.

Something Was Missing

When it was time for new MK Ruth Calderon to speak to Knesset for the first time, she told a Talmudic story and created a YouTube sensation. Her book has now been translated.

Biblical Start-Ups

A prominent Israeli novelist on novelties in the Bible.

Time Ticks Away in Portugal

Tens of thousands of Jews made their way into Portugal in waves between the fall of France in 1940 and the end of World War II. The ordeals Marion Kaplan depicts were not terribly long, but to the people who endured them, they often seemed endless.

gershonhepner

GENGHIS COHEN

Genghis Cohen was a character created by Romain Gary,

and later, in The Crying of Lot 49, by Thomas Pynchon.

With a Smith & Wesson Gary killed himself, this hara-kari

unrelated to what Thomas Pynchon would deny was pinchin'.

Plagiarism is more difficult to prove than making wordplays,

or kites which Gary wrote a book about and---wordplay!-- birdplays.

[email protected]

gershon hepner

AVANT-GARDE

The avant-garde are people who don't know

precisely where they think they want to go,

not finding being first the least bit scary,

a feeling they they share with Romain Gary.

The goal for which they principally thirst,

their chief priority, is to be first,

looking down on what is not, the past

of ll of their priorities the last.

Romain said this, or something similar,

but of him I'm not merely mimilar,

a word I coin to prove that, though it's hard

to be a member of the avant-garde,

it's possible if you can find a word

that no one till you ever read or heard,

as I have done, although I'm sure that Gary

would disagree , contrary just like Mary.

[email protected]

Samuel Heilman

I'm not sure what the point of this piece is: to summarize a book, a life, or to explain what the writer meant by a "heroic bullshit artist." If it's the first, I'd rather read the book. If it's the second, I'd rather read the biography or the memoir. If it's the last, I still don't get it.