Himmelfarb, George Eliot, and the Jews

Her subject was England—the most advanced experiment in constitutional democracy, and hence the best testing ground for whether such an experiment could succeed over time. The country had once been subject to the capricious rule of imperfect monarchs and churchmen, but by the 19th century its challenges seemed to be coming mostly from the increased rights and liberties that had been granted citizens in the name of progress. She identified those challenges and spun stories of some men and women who confronted them—and then, at the peak of her powers, she took the Jews as the measure of how well England was doing. Why the Jews?

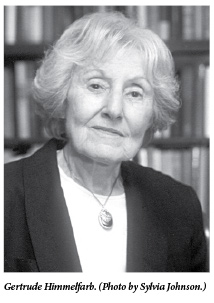

The foregoing is of course about George Eliot, whose last novel Daniel Deronda was at once a study of British liberality and of the so-called “Jewish question.” Yet it applies equally (with due distinction between the dead and the living) to the historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, renowned for her writings on 19th-century British political thinkers and actors—such as Edmund Burke, John Stuart Mill, Charles Darwin, and Lord Acton—whose latest books are The Jewish Odyssey of George Eliot, which came out in 2009, and a study of philo-Semitism in England, The People of the Book, published last year. As though following Eliot’s lead, Himmelfarb has capped her career as an intellectual historian with investigations of the same apparently minor aspect of British politics and culture. The parallel odyssey of these distinguished thinkers, separated by over a century, begs the question of how much was really at stake in England’s treatment of the Jews. Was Himmelfarb taken in by George Eliot’s exaggerated view of the matter, or has she burnished Eliot’s brilliant insight? Again, why the Jews?

The logical place to begin our inquiry is the justly famous opening of Daniel Deronda that makes it clear its author knew exactly what she was doing when she brought together her two main protagonists, introducing the heroine through the eyes of her beholder:

Was she beautiful or not beautiful? And what was the secret of form or expression which gave the dynamic quality to her glance? Was the good or the evil genius dominant in those beams? Probably the evil; else why was the effect that of unrest rather than of undisturbed charm? Why was the wish to look again felt as coercion and not as a longing in which the whole being consents?

A man observing a woman across a crowded room some enchanted evening has triggered many a fictional romance, and had this been one of them, it might have satisfied more of its readers. But Daniel Deronda is not that romantic hero. His erotic attraction to the lovely woman, soon identified as Gwendolen Harleth, is subject to moral constraint. At this point in the novel, neither Deronda nor the reader knows that he is a Jew, but Daniel already thinks as Jews are supposed to. Romantic fiction subordinates competing values to romantic love; the anti-romance is answerable to other considerations, or, rather, people with other considerations would produce an anti-romance.

“From the beginning, the ‘Jewish element’ in Daniel Deronda was seen as a problem,” Himmelfarb tells us, citing contemporary critics and several closer to our time. In fairness to them, the first part of the novel concentrates so marvelously on its heroine that one may be loath to turn away from her to the solemn young man who has misgivings about her. Gwendolen is as mercurial as Deronda is solid, as headstrong as he is cautious. Her “disturbing charm” intrigues many others besides Deronda, and she is free to use that charm to rise above the station of her birth in a society that is finally relaxing its hierarchical rigidity. We first see her at the gambling table where she indulges her appetite for risk. Lacking the talents of someone like her creator who earned her living by the pen, she cannot advance through professional accomplishment, but only through acquiring wealth, preferably through advantageous marriage. Yet Gwendolen is not without her own moral scruple, “a root of conscience in her” that curbs her pleasure and eventually curtails her ambition. All this makes us genuinely invested in her fate and curious to know how she turns out.

Critics found her male counterpart less intriguing. The influential British don F.R. Leavis once actually tried to “liberate” Gwendolen Harleth. Himmelfarb writes:

As for the bad part of Daniel Deronda, Leavis said, there was “nothing to do but cut it away.” Gwendolen Harleth had to be extricated from it and published on its own . . .The resulting novel would have some rough edges, but it would be self-sufficient and substantial.

Leavis’ publisher thought better of the plan and Gwendolen Harleth was never published. Henry James agreed that the Jewish part of Daniel Deronda was artistically deficient, but whereas James found it “at bottom cold,” presumably because Eliot’s Jewish knowledge was second-hand, Leavis felt quite the opposite, that Eliot’s emotional investment in the Jewish subject had resulted in a character who was more willed into being than fully realized in fiction. She had been “so strenuously and congenially engaged in the development of the Zionist theme” that, as a character, Deronda fell flat. For Leavis and James, Gwendolen belonged in fiction and Deronda did not.

One of Himmelfarb’s valuable contributions to this debate is her demonstration of Daniel Deronda’s unity, reinforcing the author’s insistence that everything in the book is related to everything else. Male and female protagonists are alike on the margins of their society; Gwendolen’s family suffered a sudden reduction of income and status, while Daniel has been raised in wealth but of uncertain parentage. Attracted to one another they may be, but each is looking for security that the other cannot provide. Gwendolen compromises her conscience when she marries the wealthy heir to a peerage, though she knows him to be cruel and corrupt. Daniel rescues a young Jewish immigrant and slowly uncovers the Jewish identity that is his by birth. In a brilliant footnote, Himmelfarb identifies the parallel between two scenes of drowning—the Jewish refugee Mirah Lapidoth saved from drowning by Deronda, and Gwendolen “saved, in another sense, by her husband’s drowning”—as one of several ways in which the two parts are bound together. But their interlocking lives reveal why this man and this woman are not finally joined in matrimony and why their separateness is preferable to their union.

Even to have considered pulling the book apart, as Leavis did, was akin to splitting the black and white parts of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel of which Eliot was supremely aware as she corresponded with its author, Harriet Beecher Stowe. The two novels were alike in exposing the treatment of resident minorities, but with their challenges reversed: Black Americans awaited emancipation whereas already emancipated British Jews ran the opposite risk of assimilation.

A second Jewish male in Eliot’s novel, a talented musician felicitously named Herr Klesmer, marries an English heiress, and is almost effortlessly accepted by her family and social set. So, too, the kindly Meyrick family takes Mirah into its home and wants to make her theirs. Offering herself as an example, Mrs. Meyrick says that though her father was a Scottish Calvinist and her mother a French Calvinist, she honors their memory no less by being neither. So, too, Jews and Jewesses ought to make no difference between themselves and Christians. But Mirah balks at this intended generosity:

“Oh, please not to say that,” said Mirah, the tears gathering. “It is the first unkind thing you ever said. I will not begin that. I will never separate myself from my mother’s people . . . I will always be a Jewess. I will love Christians when they are good, like you. But I will always cling to my people. I will always worship with them.”

Mirah’s Judaism teaches that the practice of goodness evolves outward from family to society rather than through a transcendent universalism that obscures distinctions. She is like Daniel in exemplifying an alternative idea of love.

Mrs. Meyrick apologizes for having offended Mirah, but the scene encapsulates the main question of the novel. Can the tolerant English tolerate those who refuse their enveloping embrace? If Jews look like us, dress like us, and want to live among us, why should they insist on remaining distinctive? Is that not illiberal? George Eliot was remarkable in noting how easily such toleration slips into its opposite when it encounters the modern Jew, who insists on remaining Jewish. It is in just this way that acceptance of Jewish particularity becomes the test case of liberal democracy. The happy ending is achievable only when the Meyricks and a soulful Gwendolen accept, however grudgingly, the need for “separation with communication” in place of miscegenation that the traditional romance would have required.

Gertrude Himmelfarb posits as one of the curiosities of literary history that the most remarkable English novel about Jews should have been written by this non-Jew who is widely regarded as the greatest English novelist of her time. Many a Jewish reader, unaccustomed to favorable representation of their co-religionists in European literature, shared her appreciation for the informed sympathy of Eliot’s portrayal. By introducing Daniel before there is any hint of his Jewishness, the author dulls any bias toward Jews (pro or con) with which we approach the book, so that we may learn about this people incrementally, with expanding sympathy, just as she herself did. Daniel’s gradual spiritual development comes through books; through visits to pawnshop, synagogue, and Sabbath table; from a parent who tried to save him from being a Jew and from a passionate Jew who reclaims him for the Jewish people. There is no climactic recognition scene of the kind that resolves other novels on the theme of identity because becoming a Jew means something more profound to Eliot than merely discovering one’s Jewish parentage.

Thus, many Jewish readers valued what others have considered the artistically deficient parts of the book, such as the extended talmudic-style debate over nationalism in a “philosophers’ club.” The author’s sympathies in this debate were the most welcome part of her description: two decades before the Zionist movement coalesced under that name, Eliot conveyed how natural, if not inevitable, she found Jewish nationalism to be. By the end of the novel Daniel resolves to restore to the Jews a political existence, “making them a nation again, giving them a national centre, such as the English have.” Who better than the English, an island people, can understand the Jews’ comparable need for political sovereignty?

Eliot’s accomplishment seems a little less “curious” than Himmelfarb suggests, if we realize that her concern was less for the Jews than for England. During her lifetime the country had removed all formal obstacles to the citizenship of Jews, received more of them into the drawing rooms, and avoided the worst of the anti-Semitism that was gathering force on the European continent. However, it still colonized parts of Asia and Africa, and as Eliot knew from personal biography, Christian liberals were almost uniformly condescending in their view of others. “Everything specifically Jewish is of a low grade,” she herself had peremptorily concluded in 1848, before she became interested in Judaism as one of the “great religions of the world.” Her growing respect for another religion and for the aspirations of another people is the enlarging experience she gives to Deronda and to Gwendolen, who finally tries to accept why Deronda does better to marry a fellow Jew. Not Zionism but England’s acceptance of the Jews as a distinct people with their own national aspirations was at stake in this novel.

Among Zionist leaders Nahum Sokolow was not alone in thinking that Daniel Deronda had “paved the way for the Balfour Declaration.” It is less certain that the English became what Eliot wished them to be. If England’s cultural-political well-being hinges on its respectful appreciation of Jewish civilization, then the anti-Israel and anti-Jewish sentiment of today’s elites must raise ever-increasing concern. The world’s foremost authority on anti-Semitism, Robert Wistrich, believes “anti-Zionist discourse in the UK probably exceeds that of most other Western societies,” and Anthony Julius, a barrister and public intellectual, has been moved by similar worries to write an 800-page history of anti-Jewishness in England.

Himmelfarb herself considers the resurgence of anti-Semitism more ominous in England than elsewhere “because it is so discordant, so out of keeping with the spirit of the country,” and she hopes that her account of the more generous currents of British thought may help to recall England to its “past glory.” Indeed, the main concern of her book on philo-Semitism, like George Eliot’s, is less with Jerusalem than with Blake’s vision of its reincarnation in England’s green and pleasant land.

In truth, Himmelfarb’s very valuable account of the philosophical and legislative arguments over the “Jewish question” shows that it had no obvious solution. The bond of religion and nationhood remains strong in England—whose monarch is also Supreme Governor of the Church of England—and durable in Judaism’s blend of nationhood with religion. The debates over how the Jewish people should be treated were duly complex, and Himmelfarb honors the process as well as the outcome by doing justice to all sides of the evolving argument. She reminds us that the terms “anti-Semitism” and “philo-Semitism” were products of one and the same noxious European political climate of the last quarter of the 19th century, anti-Semites being those who blamed the Jews and philo-Semites those who were mocked as “Jew-lovers.” The true alternative to what Wistrich calls “the longest hatred” was not Jew-love or even toleration (when it condescends) but local civic rights complemented by respect for the Jews’ equal claim to their homeland.

Himmelfarb ends The People of the Book with the finest of Englishmen, who appreciated in the Jews the same qualities that he had brought to the fore in Britain. Like Deronda and his author, Winston Churchill was an early promoter of Zionism out of conviction that the creation of a Jewish state would “from every point of view, be beneficial, and would be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.” On the eve of the Suez crisis of 1956, already retired from office, he tried to get American support for the fledgling Jewish state:

I am, of course, a Zionist, and have been ever since the Balfour Declaration. I think it is a wonderful thing that this tiny colony of Jews should have become a refuge to their compatriots in all the lands where they were persecuted so cruelly, and at the same time established themselves as the most effective fighting force in the area.

George Eliot and Churchill would have recognized in today’s hostility to Israel England’s declining moral self-confidence and collapsing strength.

As I tracked the similar “Jewish odysseys” of George Eliot and Gertrude Himmelfarb, I couldn’t help noticing that both were similarly propelled by a close friend or relative. Himmelfarb marks as “decisive” in Eliot’s development the author’s encounter with a young German Jewish scholar, Emanuel Deutsch, who at the time of their meeting in 1866 was employed in the library of the British Museum. Deutsch had just published a much-admired article on the Talmud that had caught Eliot’s attention. Through their ensuing friendship she discovered a captivating new area of study—the Jews, their history, and culture—and a living model of a Jew who could serve as an anchor for her fiction. The character Mordecai (also known as Ezra) became the inspirational source of Deronda’s evolution in the novel much in the way that Deutsch not only instructed Eliot in the ways of the Jews, but also awakened her concern for the Jews’ national predicament. Deutsch’s passion for the land of Israel and his untimely death before he could make his home there were transmuted into Mordecai’s passion and fate in the book. It is hard to imagine that Eliot would have taken such an informed interest in the Jews without Deutsch to guide her.

Gertrude Himmelfarb, known to some as Bea Kristol, widow of Irving and mother of William, knew a great deal about the Jews all along, but she appears to have taken them up as a subject following the death in 2006 of her older brother, Milton Himmelfarb. The elder Himmelfarb occupied a unique place in American Jewish letters as director of information and research services at the American Jewish Committee, editor of its yearbook, and incisive analyst of Jewish affairs. A contemporary of the so-called New York Intellectuals, many of them Jewish, who made their way into Anglo-American letters, Milton alone among them concentrated on the Jews and Judaism, and his regular appearances in Commentary over fifty years provided, in my judgment, some of the most perceptive studies ever written of Jews in their relation to America and of Judaism’s importance in the modern world. He was in fact concerned for American liberalism much in the same way as Eliot was for England’s. Eliot believed that its potency depended on the majority’s treatment of minorities, and he saw the same in reverse: the Jewish minority could prove the resiliency of liberalism only by standing up for itself.

Milton Himmelfarb published only one book of essays during his lifetime, Jews of Modernity, so it was left for Gertrude to edit a second collection, Jews and Gentiles, after he died. She concludes her introduction to this volume with the same quotation as she does her book on philo-Semitism in England:

“Hatikvah,” the Zionist and Israeli anthem, proclaims, “Our hope is not lost.” That is in answer to the contemporaries of Ezekiel (37:11), who, more than 2,500 years ago, had despaired, crying, ” . . . our hope is lost . . .” Hope is a Jewish virtue.

All of these writers—Eliot, and both Himmelfarbs—felt that this Jewish virtue, if properly understood, was also the best hope for modern times. It will have a better chance of being realized if more Jews read and absorb their fortifying books.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Brotherhood

How did the world's most antisemitic play become a symbol of positive Christian-Jewish relations? Karma Ben Johanan's new book explores an evolving dynamic.

Walkers in the City

Herman Melville was unimpressed with Jerusalem in 1857, but what would he say if he were a saunterer on Mamilla or King George today?

Standing at Sinai in Medieval Germany

An unusual illustration of revelation from the fourteenth century Tripartite Mahzor.

Irving Kristol, Edmund Burke, and the Rabbis

Irving Kristol started off as a neo-Trotskyite and famously became the “godfather of neoconservatism.” But his idiosyncratic “neo-Orthodoxy” lasted a lifetime.

slgoldenberg

A fine and insightful review

jmfredman

Wonderful article. Your series of lectures on Daniel Deronda has inspired me to purchase Himmelfarb's book on George Eliot. Thank you for making them available.