Homage to Mahj

“Any Miami Jewess worth her salt has a poolside mah jongg game once a week,” the designer Isaac Mizrahi declares in his contribution to Project Mah Jongg, which debuted at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. The show is now travelling the Jewish museum circuit introducing the rummy-like tile game to those who have never seen the craks, bams, and dots—the Chinese characters, bamboo sticks, and circles that decorate the game pieces.

After an appearance at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland, the show is now at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, with a planned engagement at the Jewish Museum of Florida running into 2013. The exhibit, which is underwritten by the National Mah Jongg League, lays out the game’s Jewish yichus in a visually appealing display designed to attract a new generation of players in the current era of resurgent poker and retro-chic.

But mah jongg is not poker, and the Jewish enclaves that nurtured it—mid-century Jewish suburbs, Jewish country clubs, Catskill resorts—have either disappeared or changed. Most importantly, of course, Jewish women, like other American women, have entered the workforce, which leaves little time for long afternoons at the mahj table.

Still, mah jongg maintains its appeal. The tiles are beautiful, feel pleasing in the hand, and swish and click satisfyingly as the game moves along. Project Mah Jongg successfully echoes the game’s aesthetic power, with tall freestanding display cases that imitate the shape and colors of mah jongg’s iconic tiles intersected by glass boxes that evoke a game table. The exhibit walks visitors through a quick history of the game: It originated in China—by legend Confucius was its creator—and grew from being a pastime of the upper-class who could afford the hand-made tiles to a recreation of the nation. It was banned in the Cultural Revolution but (like Confucius) has had a post-Mao resurgence. An American oil executive discovered the game while working in China a century ago. He published the first set of rules in English and trademarked the game’s English name, touching off a full-fledged craze in the 1920s. All-American firms such as Abercrombie & Fitch and Parker Brothers started selling the game with Chinese character tiles that was to become so closely associated with American Jewish women.

At Project Mah Jongg, nostalgic photographs of televised game lessons, players around a floating game board, and smiling women playing mahj in their bathing suits in a Catskills resort dominate the gallery walls, memorializing a disappeared world (or a postwar movie come to life) that seems simpler and yet somehow hipper than the one we inhabit today, a world we would want to step into, if we could. The exhibit doesn’t ignore the aural component of the game; CDs mounted on the gallery walls invite visitors to pull a cord to hear the sound of the game in play, with coffee being served as the tiles click and conversation bubbles up before one player admonishes, “just play, don’t talk.” At the center of the room stands a mah jongg table, set, insisting that mah jongg is to be played, not contemplated.

Interspersed throughout are newly commissioned works of mah-jongg-inspired art by famed fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, New Yorker illustrator Bruce McCall, designer Christoph Niemann, and Israeli-American writer and artist Maira Kalman. Fully three feet tall and five and a half feet long, these creations capture the eye, providing balance for the freestanding displays.

The Skirball Cultural Center, which is hosting the show in Los Angeles through early September, has planned a night of mah-jongg inspired comedy, featuring actors, writers, and producers from television shows including Dexter, Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, and Seinfeld, as well as children’s game-playing sessions and mah jongg lessons for adults, all attempts to get visitors to experience mah jongg not as a quaint cultural artifact, but a living part of Jewish America.

As beautiful as is it is physically, and with the panache of celebrity and interactive bells and whistles, the exhibit fails to satisfy. If there is anything illuminating about the game’s role in American Jewish culture or the Jewish role in the game’s history, one won’t find it here. The exhibit is also poorly labeled. One example: a large archival photo is labeled “Dorothy S. Meyerson teaching mah jongg on television, 1951.” Missing from the label is the information that Meyerson was the author of one of the first guides to mah jongg, aimed at Jews, a book that was in its fourth printing barely a year and a half after it was issued. (In its additions to the core exhibit, the Maltz Museum in Cleveland included a stunning tableau of models dressed in vintage fashion, labeled, as one expects in a museum exhibit, with maker, date, and description; the kind of information missing from the rest of the exhibit’s artifacts).

After its introduction in the United States, mah jongg took off like a rocket, with game suppliers at times unable to keep up with demand. As is true of any craze, mah jongg had its detractors from the start. It was regarded as a dangerous gambling game, tainted by its “heathen” origins, fuel for rebellious flappers, and the scourge of happy homes, as wives and mothers ignored their family in the quest for the next winning hand.

Mah jongg was also part of a larger interest in things Chinese. One case of the exhibit is devoted to Chinese-inspired objects, including a doll and teacup. They are exquisite, but like virtually everything in the display cases, are not individually labeled, and no dating or provenance is given. Nor does the exhibit dwell on the fact that at the height of the mah jongg craze with all its attendant Chinese décor and clothing, the US Congress was enacting the Johnson-Reed Act, which excluded virtually all immigration from an “Asiatic Barred Zone” (it also tightened quotas on Eastern European immigration). Popular singers of the 20s sang the lyrics to “Since Ma Is Playing Mah Jongg,” in which Pa “wants all ‘Chinks’ hung.” Chinese tsotchkes yes, actual Chinese, no.

The exhibit briefly explores mah jongg’s use as a fundraiser by groups as large as Hadassah and as small as individual synagogue sisterhoods. Here, again, however, Project Mah Jongg tells the truth without being entirely truthful. While it comfortably informs visitors that proceeds from mah jongg events sent humanitarian aid to China during World War II, donated a mobile kitchen to England under the Blitz, and raised money for Jewish refugees in Palestine “and beyond,” the exhibit shies away from specifying that the “beyond” included Jews trapped under the shadow of the Holocaust. “Jewish federations asked women to give up their weekly allowances for items such as millinery and mah jongg during the war years,” but fails to specify that cigarettes were also on the list and, more importantly, where the money raised was headed. An appeal of the time, quoted in Mah Jongg: Crak, Bam, Dot, was not so squeamish: “One hat, two puffs, three bam / They’re in a concentration camp / And here I am.”

But of course, such a somber reminder of Jewish history and American acculturation has no real place next to a “fictional ‘mah jongg collection'” from Isaac Mizrahi, with its beaded evening gown, cocktail dress, outfit for daytime and swimsuit. Mizrahi’s contribution—along with that of Maira Kalman, who writes that “Women in my family did not play mah jongg,” and German-born illustrator Christoph Niemann, who reshapes the dots and bamboo sticks of mahj tiles into kitschy Jewish symbols, including a star of David and a bowl of matzah ball soup—is not much more than a paid celebrity endorsement.

Like the four sides of the mah jongg table, Project Mah Jongg rounds out its quartet of celebrity contributions with a painting by Bruce McCall. McCall’s witty, clean-lined “Miami Mah Jongg” imagines a world in which ancient Confucian sages hand down the tradition to a group of American Jewish women in a condo high above Miami Beach. This is a good joke; but one wonders whether the curators fully appreciate the irony.

The Catskills are mountains of course, but tiles aren’t tablets. The world of American mah jongg was largely Jewish without preserving any substantive Jewishness. Is it worthwhile for Jewish museums to expend limited resources to try to create a new generation of mah jongg players, or to moon over the days when American Jewish women swished and clicked as they kvetched and kvelled?

Suggested Reading

Letters, Winter 2020

Reimagination?; Romania, Romania; Shylock and Jonah

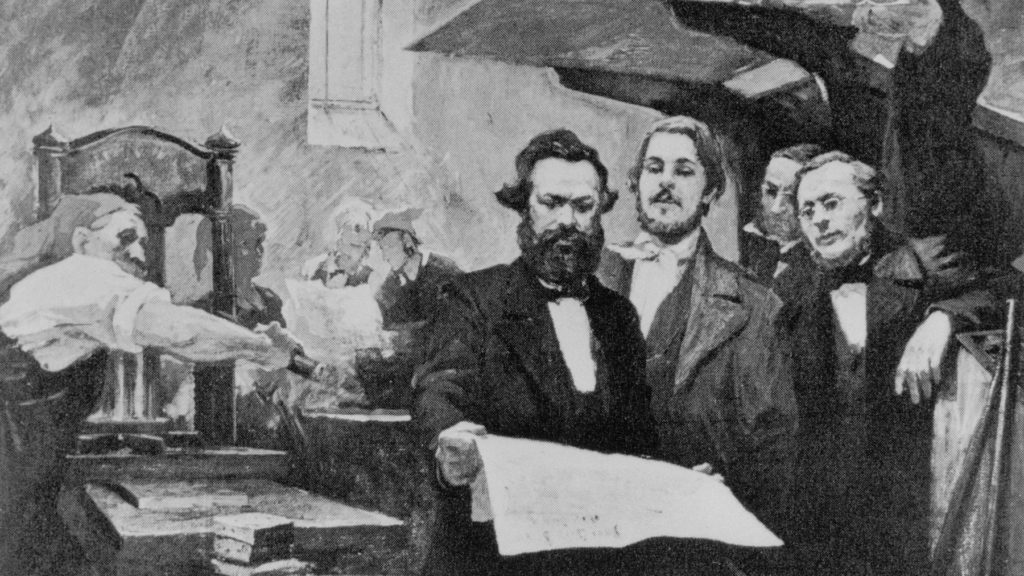

Karl Marx, Bourgeois Revolutionary

Jonathan Sperber's new biography paints Karl Marx as a surprisingly conventional 19th-century paterfamilias.

Happy Is the People Who Knows the Blast

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim of Sudilkov learned Torah with his grandfather the Ba’al Shem Tov, who later visited him in dreams. In the Degel Machaneh Efrayim, he gave the shofar blast a radical Hasidic meaning.

National Socialism, World Jewry, and the History of Being: Heidegger’s Black Notebooks

The thinking reflected in Heidegger's recently published notebooks from the 1930s is alarmingly crude. It is also much more difficult to separate from his philosophy than many would like to think.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In