How Goodly Are Your Tents, O Tel Aviv? A Symposium

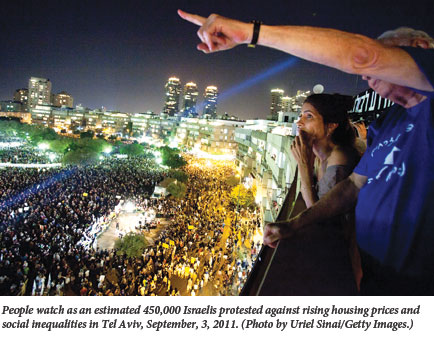

Designated by TIME magazine as the Person of the Year, the Protestor has certainly made his/her mark on the streets of many continents. Some of these award-winning protestors have toppled well-entrenched dictatorial regimes. Their counterparts in democratic countries, however, have had necessarily less clear goals and accomplishments. Overshadowed by the more earth-shaking or at least highly publicized events elsewhere, the “Tent City Protests” that began in Tel Aviv last summer have been forgotten by many outside of Israel. Nonetheless, they were extraordinary both in size-on September 3 as many as 450,000 marched throughout Israel-and civility. Perhaps inevitably, they produced a blue-ribbon commission, led by Manuel Trajtenberg, which has made a series of interesting proposals.

More importantly, the protests have had an impact on the thinking of many Israelis, especially but not exclusively, young ones. We thought that it would be useful to listen to what some thoughtful and involved Israelis are saying about what they saw or did last summer in the streets of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Some of them, like historian Orit Rozin, see the present in the light of the past. Others, like Lili Ben-Ami and Omer Moav, are focused more single-mindedly on the future. Certainly, they do not all agree on matters of policy. However, there is general agreement that something significant happened in the protests several months ago and that we have yet to see their full implications. —The Editors

How The Protests Began

by STAV SHAFFIR

Early last July, Yonatan, a good friend, phoned and asked me to join a new initiative to protest the high price of housing in Tel Aviv. The price of rent had indeed become unbearable, but was this Israel’s biggest problem? Certainly not.

However, I couldn’t refuse the invitation. Two weeks later, we were standing on Rothschild Boulevard. Our idea was to pitch tents and stay as long as we could to demonstrate that we simply couldn’t afford rent anymore. Earlier that day, the police had ordered us to cancel the demonstration because we had no permit. This actually worked in our favor by attracting more media attention. When we pitched the first tent, there were more journalists than protesters. A few hours later, thousands of people had shown up, and the next day, thousands more. Twenty-four hours later, on Friday evening, someone suggested we make a big dinner for everybody. A market nearby donated food, others brought wine, and it seemed like the entire neighborhood had joined us. When morning came, somebody was already working on constructing a field kitchen.

The protest movement offered, implicitly at first, and in time with explicit clarity, a picture of what our country should look like, of what we want it to be. We called for a first massive demonstration, where protesters shouted “The People Demand Social Justice,” and though they meant a thousand different things, we knew they weren’t all that different.

One night, I went to visit a tent city in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the country. The people who lived in those tents were not just protesters; some were families who had been queuing for housing benefits for a long time. Politically, they were on the extreme right. “You can’t represent us,” they told me the first time I came, but we sat together anyway, spending the night talking and sharing stories. In the morning I asked, “So how can I help?” They told me they needed wood to build cabins, since the conditions in the tents weren’t healthy or safe for their kids. Three days later, we had organized wood, tools, and a group of volunteers. We spent the afternoon building cabins overlooking a big, merciless highway. “Thank you,” one of the men from the neighborhood told me, “this means a lot to us. But just one thing,” he continued, “tell me, because I hear this a lot, do you work with Arabs?” I looked at him, surprised. “Yes,” I said. “Of course. We work with anybody who wants to work with us on this cause.” I waited to be berated, but the man only smiled at me and said, “That’s good. You know, some Arabs also don’t have houses.”

The key strategy of the protests last summer and fall was to be “simple.” Housing was something that mattered to all of us. Our only rule was that the protests remain nonviolent; aside from that our ideas could be developed freely. Getting together around a simple cause allowed us, for once, to forget about left and right. It took some self-control to leave parts of our ideologies aside, and focus on what we agreed upon. But we knew there was no other way.

Stav Shaffir is a journalist, musician, and graduate student at the Cohn Institute for Philosophy and History of Science and Ideas at Tel Aviv University. She was one of the leaders of the Israel Tent City Movement.

New People, New Politics

by NOAH EFRON

The People Demand Social Justice” was the motto of the summer and fall protests. It was ceaselessly chanted, set to music and recorded, ironed on t-shirts, printed on posters, auto-tuned and remixed on YouTube. Pundits, politicians, and professors have paid much attention to the slogan’s predicate (the social justice part), but little to its subject (the people).

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appointed a committee to recommend reforms, and protest leaders formed their own committees. Universities and NGOs held symposia on social justice, TV and radio news shows interviewed economists and moral philosophers about the just society, and editorial pages discussed little else. Rabbis described the ancient roots of modern social justice from their High Holiday pulpits. For a bookish philosophy major with a predilection for moralizing, there was beauty in all this earnestness. But a more important question was rarely asked: just who is this “we” demanding the social justice? Who are “the people” chanting half-a-million in unison?

It has long been an axiom of Israeli politics that one great fissure divides the nation into two: one side that holds that an agreement with the Palestinians can and should be made, and another that holds that it can’t or shouldn’t. This big division is supplemented by many smaller ones: between Jew and Arab, religious and secular, Ashkenazi and Mizrachi, immigrant and native-born. Politics has largely become the craft of advancing the interest of one or several of these “sectors”—the Shas party representing religious Sephardic Jews, Yisrael Beiteinu representing Russian immigrants, and so on. An internal report of the liberal Meretz party, leaked last year, abandoned the pretense of broad appeal; the party’s “sector,” the report said, was comprised of affluent, secular liberals living in big cities, and their needs alone should define the party platform.

The young leadership of the protests rejected this presumption of polarization, and this I believe, will be their enduring legacy. They refused to demonize the ultra-Orthodox and West Bank settlers (eagerly including their representatives among the speakers at the demonstrations). They made room for the almost always marginalized Israeli Arabs. Speaking to the hundreds of thousands on the night of the big demonstration, Daphne Leef, one of the protest leaders, said:

We are all of us imprisoned somehow in our social status, in our neighborhoods, in our religion, in our gender. And then I realized that we’re not imprisoned—it’s that we’re imprisoning us! . . . If you are a resident of Yerucham—things must change . . . If you are a pensioner or Holocaust survivor—things must change. If you are a Gaza evacuee—things must change. If you are Bedouin—things must change.

The protests brought under a single political banner supporters of the Likud, Labor, and Shas parties. There is support among settlers and among Israeli Arabs, in poorer development towns, and in tiny suburbs.

This new political ecumenism was most obvious at the tent camps, dozens of which I visited. Petach Tikvah’s encampment, for instance, brought together a socialist graduate student, a Russian alderman, a world-class Ethiopian marathon runner, an Orthodox Jewish vegetable vendor, a drug-addict bomb-shelter squatter, a labor lawyer, and a dozen others. They met for hours night after night, under the stars, to discuss their jobs, schools, apartments, hospitals, and parks. For a hundred days, these conversations took place nightly around the country among hundreds of thousands of Israelis.

The greatest changes in Israeli history have been the result of fashioning a new “we.” David Ben-Gurion and his contemporaries built the corporatist state institutions that defined the country’s first generation by hot-pressing hundreds of thousands of immigrants into Israelis through the instruments of mamlakhtiut, or statism. In 1977, Menachem Begin came to power by fashioning a new “we” of those left alienated and dispossessed by the old Labor party elite—Mizrachi, religious, and free-market types mostly. In 2011, Daphne Leef, Stav Shaffir, and their many compatriots, managed to create yet another “we.”

Even before the summer’s protests, there were signs that a realignment of Israeli politics was underway. Ariel Sharon’s Kadima party became the largest party in the country by ignoring—seemingly willing away—the divide between left and right, and seating cheek-to-jowl Über-dove Shimon Peres and unapologetic hawk Tzachi Hanegbi. (The party has now declined into sniping opportunism; but this does not erase its radical genesis.) In Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s last elections, the plurality of votes went to a party called Ir Le-kulanu (City for All) led by a second-generation communist and a Likud activist from a rough-hewn neighborhood in the poorer south of the city. (Full disclosure: I was elected to City Council as a representative of the party.) Aryeh Deri, a former Shas minister jailed for taking bribes, will soon announce the formation a new party that will be both religious and secular, Mizrachi and Ashkenazi. The protests took the nascent politics of such initiatives and gave them a young face and a passionate voice.

Just where this will all lead cannot be foretold with confidence, but I believe that my children’s children will study 2011 as a turning point in Israeli politics. For the moment, as summer and fall recede into memory, the entire country seems much like the Petach Tikvah tent camp on those warm nights: a rough and unruly assembly of uncommon people creating common cause.

Noah Efron is a senior fellow at Shacharit, a think tank for new Israeli politics, and is also one-third of “The Promised Podcast.” He teaches history and philosophy of science at Bar-Ilan University and until July 2011 served as a member of the City Council of Tel Aviv-Jaffa.

Demonstrating Dogma

by RAN BARATZ

Last summer’s protestors really did have something to complain about. The cost of living in Israel is unjustified. Too bad they went about their business in such a frivolous fashion. Lacking clear goals and presenting a fanciful economic agenda, their call for “social justice” was as loose as a welfare state’s budget and raised more questions than it answered.

Those Israelis who have blamed their government for the worst economic failures are right. However, almost all alleged market failures in Israel are actually government failures. So why do the protestors believe that the very same corrupt and incompetent government can easily solve incredibly complex economic problems? How many times do governments need to fail before Israelis start asking for less government and more society, less bureaucracy and more private enterprise, less coercion and more liberty, less “big brother” and more civic responsibility?

Welfare-state theory acknowledges the terrible consequences of nationalizing the means of production, but is still obsessed with the notion of economic equality. Its solution is to let the market run free while nationalizing (through taxation) and redistributing its produced wealth. This might work in theory, but as Adam Smith and Friedrich Hayek foresaw, it fails in practice.

The progressive contention is simple: The poor lack money; let them have the money of the middle and upper classes, and poverty will come to an end. But the record clearly shows that most western countries continuously spend a growing percentage of their GDP on social programs. This is terrible news for the welfare agenda, because it means that the welfare system is a sham: welfare creates poverty instead of abolishing it. As a result of this counter-intuitive—yet intelligible—result, a vicious circle develops. More welfare leads to more poverty, which leads to more welfare. Eventually states reach the upper limit of taxation, start increasing their national debt, and get into serious trouble.

At stake here is nothing less than the very morality of welfare statism. One might be willing to accept the dubious measures of nationalization, state coercion, and governmental supervision, if they were at least beneficial to the lower classes. But to employ these harsh measures after observing that they increase the suffering of the many, and the poor most of all, is, at least in my opinion, morally objectionable.

In Israel, welfare statism is a dogma. Right and left, Israelis welcome big governments. This is a dangerous consensus. A lack of economic education, accompanied by too much reliance on the state, leads Israelis to believe that governmental budgets are a matter of pure will, unconstrained by any form of necessity. Apply enough pressure and the government will open its ever-full coffers and shower wealth on its citizens—and on that day the people shall rejoice in “social justice.” The protests were even praised in Israel for their “citizenship,” as if good citizenship means demanding that the government use its power to transfer other people’s money to you in order to fulfill your “positive rights” (to live in Tel Aviv without paying the costs, no less).

But there is some room for optimism. There are many hard-working, responsible Israelis whose sense of self-dignity and honor—the ancient republican prerequisite of good citizenship—leads them to despise welfare, at least for themselves. This admirable sentiment, accompanied by basic economic understanding, could revive an Israel in which people take it upon themselves to provide for their families as well as to promote a healthier and more just society.

Ran Baratz teaches philosophy and history in various academic institutions and heads the Tikvah Fund‘s “Political Thought, Economics, and Strategy“ Summer Seminar at Bar-Ilan University.

Why I Protest: Teachers’ Rights

by LILI BEN-AMI

One way to understand what the 2011 protests were about is to understand the professional life of someone like my colleague Limor, a 29-year-old Tel Aviv science teacher. Limor completed an M.A. with honors at a prestigious university and has a teaching certificate. During the day, she teaches students in 10th through 12th grades; in the afternoon, at home, she takes care of her own children; and in the evening she is back on the job, writing lesson plans, grading exams, calling parents, and more. At midnight, Limor drops onto her bed exhausted and troubled because she still has so much more to do.

In Israel, the teachers in elementary and middle schools are employed by the Ministry of Education, but high school teachers are employed by municipalities and local authorities. The trend toward privatization in the country has in the past twenty years brought about a situation in which more and more cities avoid employing high school teachers directly by having recourse to different associations. Limor and her colleagues are employed by an NGO that operates on a large deficit. The NGO makes this up, in part, by “borrowing” the money that has been deducted for her pension fund. Sometimes, she doesn’t even get her salary on time. Moreover, every year, Limor receives a termination letter that prevents her from getting tenure.

It is close to impossible to teach something of value to thirty-six boisterous young Israelis in a non-air-conditioned classroom. In Israeli schools, teachers have no private workspace, no decent conference rooms. When they’re not in class, teachers are stuck in one big, overcrowded teachers’ room, where they are besieged by dozens of students every day. Between classes, the teacher has a five- to fifteen-minute break, during which she—and it is usually, and not incidentally a woman—has to hurry to make photocopies. No teacher ever has time to sit down and eat a leisurely lunch. Sometimes it isn’t even possible to make it to the bathroom or grab a cup of coffee. All of the textbooks she uses in class must be purchased with her own money. Parent-teacher conferences and other meetings take place in the evening hours, for which no one gets paid. Every year, the teacher chaperones a three- or four-day trip. In return for all of this hard work, teachers receive low salaries (the youngest earn only about 5,300 NIS a month) and little societal respect.

I have been teaching in a large high school in Jerusalem for the past five years under these deplorable conditions. Together with my colleagues, I founded the Council for the Fair Employment of Teachers. After five years of fighting for our goals, we finally received the welcome news that the school where I teach will be placed under the direct authority of the Jerusalem municipality in the coming school year. Other schools have stopped “firing” teachers every year to avoid granting tenure. Some have even reimbursed teachers for the money that was owed to them. But these are only the opening shots in a battle that will end only when all the schools in Israel are placed under proper authority. Last summer, during the protests, I spoke from the podium in Tel Aviv not only on behalf of the teachers but on behalf of all who are alarmed by the state of education in Israel. What we demand for the teachers, students, and parents of Israel is not charity but justice.

Lili Ben-Ami is a teacher, lecturer, and writer of Israel’s Ministry of Education curriculum, as well as a founder of the Council for the Fair Employment of Teachers.

Like Denmark or Like Greece?

by OMER MOAV

A month after the Tel Aviv protests began, I was invited to speak at the tent city, which was a surprise as I am known as an advocate of reduced government spending, lower taxes, and a market economy—pretty much the opposite of what many tent protestors were demanding. However, I was impressed with the respectful, curious, and deeply civil way in which they engaged with me. The protesters’ basic complaint that “our income is smaller than the expenses required to live in a dignified way” is entirely valid. But it is naïve to believe, as most of them do, that the government can close the gap between income and expenses.

While demanding increased government spending—free education; subsidized housing; higher salaries for teachers, social workers, and doctors; and so on—the protesters never really suggested how to pay for them, with the single exception of an increase in taxes on the wealthy, though they gave little thought to the costs of such a proposal. They have fallen for idealistic prescriptions of an expanded welfare state, apparently without realizing that they and their children would have to pay for it and that the principal beneficiaries would continue be those who are connected to power through the labor unions, the military, and the political parties.

I believe that the way to achieve the lower prices, higher incomes, and greater social equity that the protesters called for is to increase competition, reduce the concentration of economic power, and change governmental spending priorities. Currently, the labor unions impose huge costs and inefficiency. Meanwhile, a small number of families control a large fraction of the economy and engage in cartel behavior, while governmental tariffs and administrative restrictions on imports enable local producers to charge high prices. In addition, some sectors receive disproportionate benefits through government spending, in particular the settlements, the ultra-Orthodox, and the military.

Part of my frustration with the protesters is that they say they want an economy like Denmark’s but their proposed reforms are more consistent with one like that of Greece. It is sad to see young people calling for an economic model that inevitably ends in poverty. But I am also disappointed that the Israeli government, in particular Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, saw the protests more as a threat than as an opportunity for change.

In response to the protests, Netanyahu created a blue-ribbon committee, headed by Manuel Trajtenberg. The Trajtenberg Committee had some good ideas, but it failed to recommend the crucial reform of opening agriculture to competition, perhaps out of fear of the strong agricultural lobby group. The committee’s recommendations might not really matter, in the end, for Netanyahu and his government do not seem committed to increasing competition or truly revising budgetary priorities. Instead of increased competition and lower prices, the tax burden will probably rise as more benefits, in particular in housing, go to the ultra-Orthodox.

If it is to offer a genuine response to the valid complaints of the protestors, the government must stand up to the bullies within and without—to the ultra-Orthodox parties who hold the coalition hostage to secure more benefits for their constituents; to the head of the Histadrut (Labor Union), Ofer Eini; and to the cartels that control labor demand, prices, and production in Israel. It will have to provide better infrastructure, law enforcement, and environmental stewardship, while reducing spending on settlements, the military, and transfers to those who live on government handouts. Unfortunately this seems a long way off.

Omer Moav is professor of economics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Royal Holloway University of London. He served as the head of the advisory board to Minister of Finance Yuval Steinitz from 2009 to 2010.

Zion Shall Be Redeemed with Justice

by AARON LEIBOWITZ

On the eve of the fast of Tisha B’Av, which commemorates the destruction of the First and Second Temples, I sat on the ground of Jerusalem with fellow protesters and read the Book of Lamentations. As we recited the famous words of Jeremiah, “How has she come to sit in isolation, a city once teeming with people,” in close proximity to the same spot in which they were first spoken, the ancient sorrows intermingled with our own, culminating in the famous final verse of hope “renew our days, as they once were.”

Jeremiah was clear about the causes of the fall of Jerusalem: “[The wicked] do not plead . . . the cause of the orphan . . . and they do not defend the rights of the poor. Shall I not punish these people?” (Jer. 5:28). Of course our protest was not about destitution and overt poverty, but it was striking that it was in the month of Av that the streets of Jerusalem rang with the shout “The People Demand Social Justice.”

When people gather together to proclaim a shared truth, it is somewhat akin to communal prayer. The event itself is more significant than any particular goal. Critics have argued that the movement had no clear destination or demand. This was, perhaps, true, but the movement was rallying around something more primal and visceral, deeper then any specific issue or policy. It is on this deeper level of human hopes and cares that a spiritual framework and religious terminology become most useful.

One of the most significant questions facing us in Israel today is: to what extent does a broadly shared Jewish identity still exist here? I am not referring to shared cultural expressions such as the Hebrew language and public holidays. Rather, can there still be a true shared vision about what this country stands for and in what way it represents a profound continuation of the essence of our heritage and history? If I was doubtful in the past that we could find broad common ground, I have become more hopeful. To quote another prophet, “Zion shall be redeemed with justice, and those who return to her will do so with righteousness.” (Isaiah 1:27)

Aaron Leibowitz lives in Jerusalem where he heads the Sulam Yakov Rabbinical Academy.

Sumer Protests: 1949 and Now

by ORIT ROZIN

ast summer, young Israelis exchanged the comfort of their air conditioned homes for the heat of the day in the public square, settling into the beating heart of Israel, Tel Aviv’s Rothschild Boulevard, not far from the spot where the independence of the State of Israel was first proclaimed in 1948. It was impossible, for me at least, not to think of their predecessors, in the spring and summer of 1949.

Right after the conclusion of the War of Independence, there was a wave of demonstrations and protests throughout Israel. Most of the protestors were new immigrants, but newly released soldiers and veteran settlers also joined. In 1949, the residents of Lod—all of them new immigrants—protested not only the lack of jobs but also shortages in electricity, water, and even of bread and flour. That same month, immigrants living in Ramleh went to Tel Aviv to demonstrate in front of the Knesset, which had not yet moved to Jerusalem. When they demanded jobs, officials at the Ministry of Labor promised that they would get them, giving the immigrants free rent and electricity, for the time being.

Other immigrants were protesting in the camps that had been set up for them. There, the government already took care of their basic needs but living conditions were grim. In Pardes Channah, immigrants went on a twenty-four-hour hunger strike. The Jewish Agency and the ruling party, Mapai (the once-powerful precursor of today’s diminutive Labor party), regarded the situation as explosive. The camp administrator fretted that “a single match could set off a terrible conflagration here.”

These protests spread to nearby Netanya and Hadera, as well as other, more distant towns. In July, protestors from Ramleh returned to the government offices in Tel Aviv and staged a sit-down strike that resulted in bloody clashes with police. The strike ended only when then-Minister of Labor Golda Meir made a midnight visit to the protestors and promised hundreds of new jobs. In short, the protests had a significant effect in those days when Israel was governed by people who believed it was their duty to care for the unemployed, the sick, the hungry, and the elderly, and that the responsibility for doing so should be shared by the entire population of the country.

Unlike the demonstrations that erupted in Israel’s first years, those of last summer were the work of middle-class people angered by the rising cost of living. They were joined, however, by some members of the lower classes who shared their feeling that the neo-liberal policies of recent years had placed control of their lives not in an Invisible Hand but in the greedy fingers of a handful of oligarchs. But the success of the protests had to do with something more than financial grievances. Anyone who paid careful attention to the medley of voices that emerged from the tents on Rothschild Boulevard saw and heard something else that lay beneath the call for social justice. Like the protestors in 1949, they insisted not only on their right to speak out, but on their right to be recognized as social agents.

As in 1949, we Israelis find ourselves in a transitional period. Once it was the new immigrants who struggled to obtain greater control over their own destiny; now it is the middle class who feel that their rights are vanishing along with their economic well being. They went out into the streets to return Israeli public discourse to its founding promise to “ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants.”

Orit Rozin is professor of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University and the author of The Rise of the Individual in 1950s Israel: A Challenge to Collectivism (Brandeis University Press).

Suggested Reading

Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

Readjusting Sights

Reams of military history, and recollections by generals have been written on Israel’s many wars, but in this bookish country, Haim Sabato is one of the few Israeli soldiers to write a truly literary memoir.

Before & After October 7: A Symposium

We asked distinguished friends and contributors a simple question: what did you believe before October 7 that you no longer believe?

State and Counterstate

Debates about Zion and its relation to the diaspora aren't new. David Myers and Noam Pianko have retrieved the forgotten ideas of several interesting figures, foremost among them Simon Rawidowicz. Do they speak to us now?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In