Israel and the Old-New Middle East

Dramatic events are unfolding before our eyes in the Middle East. From the shores of the Atlantic, in Morocco, to the coast of the Persian Gulf in countries such as Bahrain and Iran, countless demonstrators gather in the central squares of cities large and small to vent their rage against their rulers and demand change in their countries. Remarkably, they have succeeded in Tunisia and Egypt. Throughout the region, longstanding authoritarian regimes are under great duress, and, as I write, the violence in Libya continues.

The trajectory of these events is not yet clear. One thing, however, is unmistakable: The many observers in the West naïvely expressing hope for a rapid transition to democracy display ignorance of the social and political realities of North Africa and the Middle East. It is far too soon to herald the “Jasmine Revolution” in Tunisia or the toppling of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak as victories of people power over the forces of reaction.

While longing for freedom is basic to humanity, so is the need for political stability. Dictators have long been able to rule much of the world because they understand the human fear of chaos. The social contract upon which most states are founded is predicated on providing security and stability—not freedom. In fact, democracies are a relatively new socio-political phenomenon—the result of a long and complex historical process. Despite exposure for more than a century to Western cultural influence, the Arab world has failed in many respects to modernize. The crowds in the street, whose courage is commendable, are not enough to build new democracies. Middle Eastern societies, deeply attached to Islamic traditions, will not suddenly adhere to a liberal-democratic ethos. Unfortunately, the cultivation of a democratic political culture simply takes more time than some Western pundits would like to believe, and the absence of an organized democratic alternative to dictatorship in the Arab states and Iran is a recipe for political instability.

In Lebanon, the democratic hopes generated by the “Cedar Revolution” did not prevent the Hezbollization of the country. Similarly, the praiseworthy hopes of the Egyptian masses for a more open and just political system might be hijacked in free elections by the politically organized Muslim Brotherhood, whose commitment to democracy is non-existent.

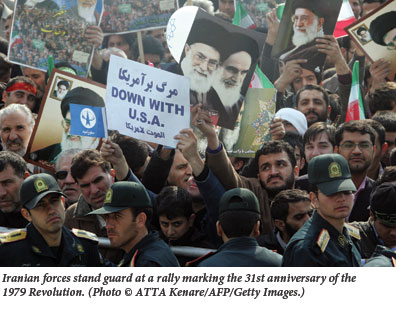

Resistance to democratization will persist in many quarters. For example, we have seen the Saudi intervention in Bahrain to preserve the rule of a Sunni dynasty. The Middle Eastern regimes’ inclination and capacity to suppress their people should not be underestimated. The tenacity of the ruling groups in clinging uninhibitedly to power—when their only alternative is torture and death in the streets—has been clearly seen in the grim performances of the Revolutionary Guard in Iran and Muammar Gaddafi’s mercenaries in Libya. The ruling Alawite minority in Syria may well follow suit.

Another clear result of the recent events is the further erosion of the US position in the Middle East. The rulers of the pro-American states have learned again that when push comes to shove, America cannot be trusted. As the ground shifted in the Middle East, the Obama administration delivered confused, contradictory, and inconsistent responses. First, there was a quick demand for Mubarak’s departure, and then there was support for the military regime, followed by a hesitant and muted condemnation of Gaddafi’s violent repression before taking action. American encouragement of the Egyptian demonstrations against Mubarak was viewed by leaders in Amman, Kuwait City, Rabat, and Riyadh as the betrayal of a friend and ally. President Obama seems susceptible to the “Carter Syndrome” that helped to undermine the Iranian Shah. Unfortunately, Obama’s behavior is dangerous for America’s friends. It strengthens the general perception of a weak and confused American foreign policy. What leaders in the Middle East see is an American retreat from Iraq and Afghanistan, feeble attempts to “engage” America’s enemies (Iran and Syria), and desertion of old friends. As rulers in the pro-American states conclude that they cannot rely on US support, they will distance themselves from Washington.

Whatever happens in Egypt will have repercussions throughout the region. At the moment, the pro-Western Egyptian regime seems to have weathered the crisis by sacrificing Hosni Mubarak and promising elections and reform. It remains to be seen how well the Egyptian generals deliver and whether they are capable of forming useful coalitions with liberal forces in the middle class in order to neutralize the only well-organized political force outside the ruling government: the Muslim Brotherhood. In any case, in the near future we will see a weakened regime and much uncertainty.

Whatever happens in Egypt will have repercussions throughout the region. At the moment, the pro-Western Egyptian regime seems to have weathered the crisis by sacrificing Hosni Mubarak and promising elections and reform. It remains to be seen how well the Egyptian generals deliver and whether they are capable of forming useful coalitions with liberal forces in the middle class in order to neutralize the only well-organized political force outside the ruling government: the Muslim Brotherhood. In any case, in the near future we will see a weakened regime and much uncertainty.

How the diminutive nation of Bahrain emerges from this crisis will also be important, and not only due to its strategic location in the Persian Gulf and its role as host of the US Fifth Fleet headquarters. The majority of Bahrain’s population consists of Arab Shiites. Until now, they seem to have identified primarily as Arabs and thus been amenable to living under a Sunni Arab monarchy. But if the religious Shiite component of their identity comes to overshadow the ethnic Arab dimension, they might push for the establishment of a pro-Iranian government or even annexation to Iran. Such a shift in identity could be disastrous for Saudi Arabia. Its eastern province, where much of its oil riches are situated, is mostly inhabited by Arab Shiites. Greater Iranian influence among the Saudi Shiites could bring about the loss of Saudi sovereignty over the eastern province and the loss of oil revenues to the Saudi government, which might also affect the stability of the Kingdom. Neighboring oil-rich Kuwait also has a sizable Shiite minority that is susceptible to Iranian subversion.

Similarly, the future of Iraq will be largely determined by identity politics. If current efforts at nation-building fail to sustain a strong Iraqi identity and religious divisions are not diminished, the proximity of Shiite Iran could pull the Iraqi Shiite South toward sectarianism and separatism. Iraq’s future is of course linked to the way in which American performance is viewed in the region. Interestingly, the fragile democratically elected Iraqi government has been only slightly affected by the regional wave of unrest, probably because many Iraqis are hoping that the current Shiite-dominated regime can provide a modicum of stability. In any case, Iraq is proof that transition from a dictatorial regime is a lengthy and bloody process.

There is also a real chance that additional Arab states torn by civil war might become “failed states.” Alternatively, the ruling governments will be busy parrying increased domestic challenges. This will reduce their ability to project power and combat the growing Iranian or Turkish regional influence.

Indeed, the first to gain from regional unrest is Egypt’s regional rival, the Islamic Republic of Iran. An Egypt beleaguered by domestic problems, however, will have little energy to focus on countering Iran’s nuclear aspirations. Knowing this, Iran tried to destabilize the Mubarak regime two years ago by sending Hezbollah terrorists via Hamas-ruled Gaza into Egypt. More recently, it openly encouraged the anti-Mubarak demonstrators to topple the military-based regime. It should be no surprise to find out that Iranian agents were fomenting trouble in the streets of Cairo during the protests.

Instability in Bahrain definitely enhances the position of Iran in the Gulf and in the energy sector. Unrest in Kuwait would bring this country into the Iranian orbit, and Iran would further benefit if Baghdad distances itself from a retreating US.

The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt will also be a beneficiary in the unfolding events, if the army-based regime becomes weaker. Incredibly, the Muslim Brotherhood has recently received a great deal of positive publicity, and is often portrayed in the Western media as a moderate Muslim political actor. Such superficial coverage willfully overlooks its extreme anti-Western, anti-modernist positions, not to mention its rabid anti-Semitism. The organization’s famous credo doesn’t hide its political philosophy or ambitions, “Allah is our objective. The Prophet is our leader. Qur’an is our constitution. Jihad is our way. Dying in the service of Allah is our greatest hope.” No one should forget that its ultimate goal is to establish an Islamic republic in Egypt.

The troubles in Egypt were also welcomed by Turkey’s Islamist ruling party, the AKP. Under the AKP, Turkey has distanced itself from the West and joined the radical axis in the Middle East, supporting Hezbollah, Hamas, and Iran. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is leading the country in an increasingly authoritarian direction, infringing on freedom of the press, limiting the power of the judiciary, and increasingly intimidating political opponents. The notion that the current Turkish regime could become a model for transition toward democracy in the Arab world reflects ignorance of what is taking place in Turkey.

Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, is another beneficiary of the current crisis. The Mubarak regime, a bitter opponent of the group, cooperated with Israel in the attempt to isolate and weaken its rule in Gaza. If Egypt falls to Islamic rule, Hamas will be able to break out of the Egyptian-Israeli quarantine and enhance its access to Iran.

Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, is another beneficiary of the current crisis. The Mubarak regime, a bitter opponent of the group, cooperated with Israel in the attempt to isolate and weaken its rule in Gaza. If Egypt falls to Islamic rule, Hamas will be able to break out of the Egyptian-Israeli quarantine and enhance its access to Iran.

The turmoil in Egypt is unquestionably another boon for the Iran-led radical forces in the Middle East. It follows the takeover of Lebanon by Hezbollah, Iran’s Lebanese proxy, which undid several years of American and European attempts to strengthen the pro-Western, pro-democratic forces. Unfortunately, these elements are not ready to put up a fight, but prefer stability to armed struggle. The greater prominence of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and its recently gained (and entirely spurious) respectability will also bolster the cause of the radical Islamists everywhere in the region.

American weakness could induce an avalanche effect that could lead the existing Arab governments to succumb to Iranian pressure. The ripple effects of the widespread socio-political malaise within the Arab world could paralyze the foreign policy of Arab states and make strategic cooperation with the US more precarious. This could create a regional environment in which Iran’s freedom of action would be enhanced and its ability to take over the oil and gas fields in its vicinity in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Basin increased. It could also increase the likelihood of Iran’s crossing of the nuclear threshold, thus dramatically changing the regional balance of power.

Israel is watching the recent developments with great concern. Israelis ask whether the current American administration is capable of exercising sound strategic judgment and standing by its allies. Jerusalem is astute enough to realize that the demonstrating crowds represent a much greater potential for radicalization than democratization. It concurs with many Arab leaders that courting favor with the demonstrators undermines pro-American regimes and regional stability. Moreover, it realizes that the popular sentiment in the Arab world is largely anti-Western and, needless to say, anti-Israel. While Israel would welcome peaceful democratic neighbors, its thinking is guided by a worst-case analysis.

Israel’s fears focus on Egypt and the implications of a policy change concerning the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty, which has been one of the pillars of Israel’s national security. Sadat’s defection from the Arab military coalition removed the strongest military force from Israel’s list of enemies, enormously improving the country’s strategic situation. Moreover, the peace with Egypt deprived the other Arab states of the ability to launch a two-front war against Israel. The demilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula further stabilized the strategic Egyptian-Israeli relationship by denying either side the option of a surprise attack. Jerusalem fears, above all, an Islamist takeover of Egypt, which would indeed be a strategic nightmare.

This has not yet happened, since the Egyptian military continues to control the country and has announced its support for keeping Egypt’s international commitments. In all probability, the direction of Egyptian politics will not change radically in the near future, which is good news for Israel. But, the new regime will be weaker than the previous one and would probably prefer not to be burdened with the Israeli relationship. This means that the always “cold peace” might very soon become even chillier.

Another troublesome aspect of the situation in Egypt is the erosion of the country’s sovereignty in the Sinai, which borders the Gaza Strip. During the recent turmoil, several Egyptian police stations were attacked by Sinai Bedouins, whose smuggling activities had previously been constrained by the Egyptian police. This police presence was only somewhat effective in preventing Iranian arms from flowing via Sinai to Gaza, and will probably become even less so, allowing Hamas to further enhance its arsenal of missiles. The Sinai could, in fact, become a haven for terrorists, as parts of Lebanon are now.

Another troublesome aspect of the situation in Egypt is the erosion of the country’s sovereignty in the Sinai, which borders the Gaza Strip. During the recent turmoil, several Egyptian police stations were attacked by Sinai Bedouins, whose smuggling activities had previously been constrained by the Egyptian police. This police presence was only somewhat effective in preventing Iranian arms from flowing via Sinai to Gaza, and will probably become even less so, allowing Hamas to further enhance its arsenal of missiles. The Sinai could, in fact, become a haven for terrorists, as parts of Lebanon are now.

Jerusalem is also monitoring developments in Jordan, the neighbor with which it shares its longest border, and which is located closest to Israel’s heartland—the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem-Haifa triangle that holds most of the country’s population and economic infrastructure. While Israel regards Jordan as providing a strategic buffer zone on its eastern border, the Jordanian elite see Israel as an insurance policy against invasions from its neighbors. So far, King Abdullah has been successful in riding the current Middle East storm with minimal damage to his rule and to relations with Israel. However, if Iraq falls to the radicals, the pressure on the Hashemites will grow again.

The unprecedented events in the region have deflected attention from the Palestinian issue, and the demonstrations are obviously not fueled by concern for the Palestinians. Still, experience suggests that eventually Israel will be blamed, if only partially, for the radicalization of the Muslim street. Consequently, misguided attempts “to solve” the insoluble Israeli-Palestinian conflict will likely ensue. Slogans about the “urgency” of peace between Israelis and Palestinians and about the need to capitalize upon “the last window of opportunity” will be revived. Yet, the slim chances for a stable agreement are becoming more remote as the fragile Palestinian Authority faces increasing pressure from a more powerful and popular Hamas. Indeed, the virulently anti-Israel Hamas, encouraged by the developments in Egypt, might adopt a more aggressive posture toward the Jewish state.

As the region seems less receptive to peace overtures, Israel must prepare for a deteriorating strategic environment. Domestic changes, beyond Israel’s control, have brought about a reorientation in the foreign policy of important regional powers that were once Israel’s allies. The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran heralded the rise of a potent ideologically driven rival. The entrenchment in Turkish politics of the Islamist AKP, after the 2007 electoral victory, moved this pivotal state into the anti-Israel camp. And the situation in Egypt and Jordan may not be hopeless, but it is certainly

precarious.

Jerusalem must therefore continue to pay close attention to the capability of its nearby and distant neighbors to harm it. The Middle East turmoil is generally weakening the Arab states and giving Iran greater opportunities to extend its reach. The strategic fatigue of the US also opens up opportunities in the Middle East for its rivals, China and Russia—not a prospect welcomed by Israel. Thus, the current unrest in the region is a warning bell for Israel to improve its defenses in case the situation worsens. Israel is a strong state with a remarkable military machine. Yet, it has neglected its capacity to wage large-scale wars. The last such war was in 1973. Since then, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has been preoccupied with small wars and non-state actors.

Israel must invest in building a stronger force that is able to deal with a variety of contingencies, including large-scale war. This means expanding the IDF and updating its strategic scenarios. Since force-building is a lengthy process, appropriate decisions on force structure and budget allocations are required as soon as possible. Dealing with missiles of a variety of ranges has been on the national security agenda for at least two decades. Budgetary constraints have slowed development and adequate deployment of a multi-layered missile defense system. This situation needs to be remedied as the radical forces’ motivation to attack Israel grows. Fortunately, Israel’s flourishing economy can afford larger defense outlays to meet its national security challenges.

The Middle East is a rough neighborhood and may be getting rougher.

–March 29, 2011

Suggested Reading

On Not Bringing Up Baby

What happens when the rising cost of raising children meets the downward pressure on reproduction?

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

In a new exhibit at the Met curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that Jerusalem's crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism.

Redesecration and Solidarity in Greece

“Even if they vandalize the monuments one hundred times we will repair them one hundred and ten times,” pledged Yiannis Boutaris, the mayor of Thessaloniki, after the latest act of anti-Semitic destruction in the city.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In