In the Melting Pot

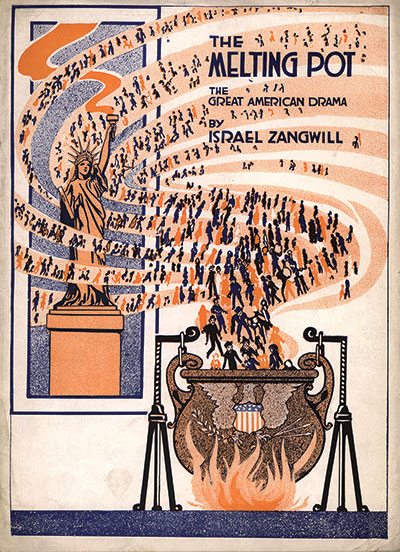

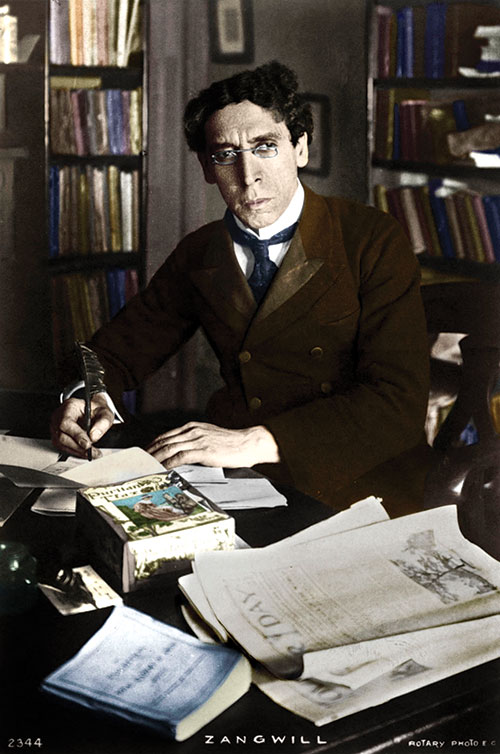

“That’s a great play, Mr. Zangwill, that’s a great play.” President Theodore Roosevelt famously shouted out these words to Israel Zangwill as the curtain went down on the Washington, D.C., premiere of the British Jewish author’s The Melting Pot in October 1908. The president, who on later occasions explicitly deplored the very notion of “hyphenated Americans,” could only have been pleased by a drama whose Jewish hero celebrated America as “God’s Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and re-forming,” and where, out of “Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians . . . God is making the American.”

Even before the performance of the play and the universal adoption of its title as a metaphor for the process of complete assimilation, American Jews had been busy devising means of withstanding the pressures that Zangwill welcomed. Among other things, they founded (or rather, refounded) in 1888 the Jewish Publication Society. One of the first works the society published was what Jonathan Sarna has called “the first best-selling Jewish novel in America,” Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto—a book that sensitively depicted the lives of Eastern European Jewish immigrants in London (without pointing hopefully to their disappearance through assimilation).

Zangwill was also for a time one of the most important figures in the Zionist movement, a key ally of Theodor Herzl in its earliest days and one of his ardent supporters until Herzl died in 1904. Zangwill left Zionism the following year, in protest against the movement’s principled rejection of any territory other than Palestine as a destination for Jewish settlement, but he remained a nationalist activist. For 20 years he led the Jewish Territorial Organization, which scoured the world, from Australia to North Africa to southern Africa, in search of an alternative site for a homeland for his people.

Zangwill’s politics might seem inconsistent, but he was not really of two minds. He mostly felt that the anomalous, vulnerable existence of the Jews as a scorned minority had to be brought to an end, one way or another. Dissolve them among others or collect them together and grant them some measure of autonomy in one of the world’s underpopulated places—whatever worked, whatever could put an end to anti-Semitism, was worth doing. For Zangwill, the preservation of the Jewish people as such was not a priority.

One Zionist of the same era who saw things very differently was Horace Kallen, a professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, who in 1915 published in The Nation a famous retort to Zangwill (and others) entitled “Democracy Versus the Melting Pot.” The wayward son of an immigrant Austro-Hungarian Orthodox rabbi, Kallen for a time welcomed the dissolution of the Jews, but he eventually concluded that people “may change their clothes, their politics, their wives, their religions, their philosophies,” but “[t]hey cannot change their grandfathers.” Since the “selfhood which is inalienable” in different nationalities is ancestrally determined, their respective efforts at “self-realization” would necessarily have to take very different forms.

Therefore, instead of looking forward to the consolidation of a single identity within what he called the American “commonwealth,” Kallen advocated the creation of conditions that would facilitate “the realization of the distinctive individuality of each natio that composes it.” Each people should be able to express “its emotional and voluntary life in its own language, in its own inevitable aesthetic and intellectual forms.” Even as they underwent Americanization, the Poles would do this in Polish, the Italians in Italian, and the Jews, ideally, in Hebrew or Yiddish, in innovative ways. The New World would succeed where the old one had failed.

The “American civilization” may come to mean the perfection of the cooperative harmonies of “European civilization,” the waste, the squalor, and the distress of Europe being eliminated—a multiplicity in a unity, an orchestration of mankind.

Or, in an influential phrase Kallen patched together a decade later, America would become a land of “cultural pluralism.”

Who came closer to prophesying what America would really be like in the middle years of the 20th century, Zangwill or Kallen? In 1963, Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously—if not wholly accurately—declared in their book Beyond the Melting Pot that “the point about the melting pot . . . is that it did not happen,” not in New York, at any rate, or other big cities that resembled it. Americans, by and large, kept their ethnic identities, if not, for the most part, their languages of origin. And certainly, it has been relatively easy in the half-century since Glazer and Moynihan published their book to be a “hyphenated American,” and a Jewish American in particular. For baby boomers like me who have spent much of our lives exploring what Kallen called the “aesthetic and intellectual forms” of Jewish culture in these years, the United States has truly been, to borrow the famous phrase coined more than 100 years ago by the forgotten German Jewish banker and writer Ludwig Max Goldberger, “a land of unlimited possibilities.”

I myself have explored a considerable number of them. I have, in fact, done little else in my life, whose way stations have included Camp Ramah, the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Brandeis, positions in Judaic studies at several American universities, teaching in Meah and other adult education programs, and working with various Jewish educational foundations. I’ve also translated a couple of Jewish classics and produced a fair amount of scholarly work on Jewish thought and history, edited the magazine of the Association for Jewish Studies, and helped to edit the publication you’re now reading. My role in the Jewish section of Kallen’s American orchestra has not by any means been a major one, but I have found it fulfilling. Far from having any regrets, I’d do it all over again (and I’m not yet ready to stop).

Yet I have to say, too, that I’ve never been able to escape, from the very beginning, a sense that I was fighting a losing battle. I can remember, for instance, a serious talk about the future that another camper and I had with a counselor named Rafi in a rowboat on the lake belonging to Camp Ramah in Connecticut in 1964. Rafi told us something that we had both heard before, but earnestly and compellingly enough for me to remember the tone of it, if not the exact words, more than a half-century later. We had to go back home, he told us, and remake our communities in the image of the camp. We had to make our camp Hebrew the communities’ Hebrew, our Shabbat their Shabbat, our ruach (spirit) their ruach. Our job was to build a future in which it was not just the rabbi and a small coterie of his supporters who lived genuinely Conservative Jewish lives but the whole congregation.

I didn’t argue with Rafi, but as he spoke I thought of all of my classmates who had dropped out of Hebrew school right after their bar and bat mitzvahs. What could we, the remnant still enrolled and more or less inspired, possibly do to turn them around? How could we ever induce them to prefer Friday night services to movies and Saturday morning services to playing golf or skiing? It seemed far more likely that we would slip away, one by one, to join them.

Since that day on the boat, I’ve heard a lot of other pep talks. I’ve even given some. And I’ve been part of a number of Jewish programs and projects that have fared quite well. But I’ve never felt like I was on the winning team. Even when I have taken pride in the real accomplishments of the various associations and institutions in which I have been involved, I have never lost sight of the large and ever-increasing distance between people more or less like me and the great majority of Jews in America.

According to the Pew Research Center, there are now in the United States 4.2 million people who profess the Jewish religion and another 1.2 million who do not but still identify as Jews (not to mention the 2.4 million who acknowledge some Jewish background but affirm no Jewish identity at all). Every reader of this essay has no doubt already seen the discouraging statistics that chart the disaffiliation of very large numbers of those who still identify as Jews from organized Jewish life, the steep rise in intermarriage over the past half-century, and the low percentage of children of intermarried Jews who are being raised as Jews, so I won’t dwell on them.

Rather, I will note that according to the Pew survey only half of the Jews in this country can read the Hebrew alphabet, and of them only a small fraction (one-quarter, supposedly, but I find it hard to believe it’s that high) say that they can read Hebrew texts with comprehension. Unfortunately, the survey doesn’t tally how many people know, for instance, what the Mishnah is, who the Gaon of Vilna was, or when the Kishinev pogrom took place, but I’m sure that if it did we would see evidence of massive ignorance. This, at least, is what my own experience leads me to believe. Outside of my usual Jewish haunts, I less and less often meet Jews who know or care very much about Jewish culture or religion. While there are exceptions to the rule, the typical Jews I meet are evidence not of a thriving cultural pluralism but of the widespread disappearance of the selfhood Kallen thought to be intrinsic and inalienable. It turns out that it doesn’t really matter that much whom your grandparents were. Glazer and Moynihan notwithstanding, we never really got beyond the melting pot.

It is possible to remain undaunted by the sight of massive defections from the Jewish people and the widespread dissolution of Jewish consciousness. There are, after all, still millions of Jews in America, and as Rabbi Tarfon reminded us a long time ago, our inability to complete a task doesn’t leave us free to desist from it. The American Jewish world is full of leaders, scholars, and activists who know that the odds are against them but nevertheless continue to fight to hold onto what has not been lost and even to make gains. Who knows, after all, what’s going to happen? The Jewish future has often looked bleaker than it does in this country today.

It doesn’t look especially bleak to some people who see no binary opposition between the ideals of the melting pot and cultural pluralism. The distinguished historian David Biale, for one, in an essay that he published 20 years ago entitled “American Symphony or Melting Pot?,” argued that there was no reason why one couldn’t uphold both at the same time. “After nearly a century of counterarguments,” he trenchantly wrote, “Zangwill’s melting pot continues to simmer.” But “postethnic theory” offered grounds for hoping that it would not dissolve everything that is Jewish into something new and unrecognizable.

[I]nstead of simply asserting a new amalgam identity, it is possible for a multiracial or multiethnic person to identify at one and the same time as both Irish and Italian, or both black and white, or even Jew and Christian. That is, in place of a new, monolithic identity to take the place of the ethnic or racial identities that make it up, one could imagine multiple identities held simultaneously and chosen as much as inherited. To put it in Horace Kallen’s terms, we may not be able to choose our grandparents, but we can choose the extent to which we affirm our connection to this or that grandparent. Freed of its early essentialism, Kallen’s cultural pluralism can be resurrected by communities of choice.

Seen in this light, the extremely high intermarriage rate (the figure Biale cited in 1998 was 30 percent; it’s now double that) need not be a cause for alarm. “Far from siphoning off the Jewish gene pool, perhaps intermarriage needs to be seen instead as creating new forms of identity, including multiple identities, that will reshape what it means to be Jewish in ways we can only begin to imagine. For the first time in Jewish history, there are children of mixed marriages who violate the ‘law of excluded middle’ by asserting that they are simultaneously Jewish and Christian or Jewish and Italian.”

Biale went perhaps a bit too far here. That one could be Jewish and Italian at the same time, even if one wasn’t the product of a mixed marriage, was, as Biale knows, always a possibility. And even after the disappearance of the ancient Jewish Christian sects individual Jews have occasionally insisted that in becoming Christians, they have not abandoned but only completed their Jewish identities (Father Daniel, for instance, the Jewish-born hero of the Holocaust era who made aliyah from Poland in the 1950s as a Catholic priest). A century ago, viewing things from a different perspective, the secular Jewish intellectual Chaim Zhitlovsky came to a similar conclusion, insisting that there was no reason why a Jew couldn’t profess the Christian faith (preferably, in Yiddish!), since one’s Jewish identity was not a religious matter. But these quibbles aside, it is clear that Biale’s examples were designed to shock—and to suggest that just about any identity at all could be fruitfully combined with a Jewish one and still fall under some Jewish rubric.

Biale was not unrestrained, however, in his enthusiasm for this brave new world. “Whether these new forms of identity spell the end of the Jewish people or its continuation in some new guise,” he concluded, “cannot be easily predicted since there is no true historical precedent for this development.” Another prominent professor of Jewish studies, Shaul Magid, writing 15 years after Biale, welcomed the emergence of a postethnic America without fretting much about whether it would undermine the existence of the Jewish people, an entity whose survival is evidently of less concern to him than the evolution of the religion he dubiously describes as Judaism. I won’t repeat here my reservations about Magid’s case for what I called “cosmotheism with a post-Jewish face” (see “All-American, Post-Everything,” Fall 2013, Jewish Review of Books), but I do want to take a cue from him. He usefully pointed out a few locations on the Internet where one can find these inventive new forms of Jewish identity that are coming into being. “One of the largest,” he wrote, “www.half-jewish.net, is more than a support group. It is an advocacy organization that seeks to be a voice for the inclusion of multiethnic Jews in the Jewish community. On this website we read, ‘Some of us are contented Christians, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists, but we’d like to learn more about our Jewish “half” in ways that don’t involve leaving our current faith or culture.’”

I recently went back to this website in search of revealing statements by new kinds of Jews, but what I found, for the most part, was evidence of divided souls groping for greater clarity about their personal situations and some helpful information about the attitudes of different sectors of the Jewish community toward people of partly Jewish origin who were not halakhically Jewish. But there were also “Christian resources” that directed “half-Jews” to Lauren Winner’s Girl Meets God, a patrilineal half-Jewish woman’s description of “her long journey from Reform Judaism to Orthodox Judaism to the Episcopal Church and evangelical Christian views” and to “a long-distance Messianic Jewish teaching institute.”

Despite the lack of positive evidence at www.half-jewish.net, it may very well be the case that here and there new idiosyncratic forms of mixed Jewish identity are coming into being. But I doubt there are any that will have anything more than a short half-life. What I do perceive—everywhere—are last gasps. I hear them, for instance, when acquaintances tell me, radiating a little bit of nachas, that their grandchildren, who are hard to classify as either Jews or non-Jews, have something of a liking for latkes. At the same time, they tell me that the kids also celebrate Christmas (only at home and with no trace of Jesus!).

Melting pot blends of this sort, and not innovative syntheses, are what’s really happening on the ground, all over America. While I do not mean to be dismissive of the integrity and goodwill of those who are piecing together such composite identities, I fully expect that in the long run their experiments will lead, with a few individual exceptions, to non-Jewish grandchildren for whom the fact that they had some Jewish (or half-Jewish) grandparents is not much more than a genealogical curiosity.

There are, however, much less radical experiments taking place within the American Jewish community that are at least somewhat more promising. Jack Wertheimer provides a panoramic overview of them in his soon-to-be-published and thought-provoking book The New American Judaism. A professor of American Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary, and formerly the provost of that institution, Wertheimer has over the years written many penetrating studies of the American Jewish condition, all of which reflect a keen, deeply informed understanding of the disintegration that has taken place as well as a persistent refusal to acknowledge its inevitability. There is plenty in his new book, too, to reinforce the fears of pessimists like me. But he also sees many signs of vitality. Within the admittedly ailing Conservative movement, for instance, a considerable number of rabbis are now ambitiously “playing to the themes of the day: inclusiveness, spirituality, musical creativity, shorter services, nonjudgmentalism, personalized attention, caring communities, relational Judaism, and Judaism beyond the walls of the synagogue.” In the “more cohesive, participatory and spirited communities” they are forging, “the elite meet the folk where they are” (instead of the other way around, as my old counselor Rafi, and the old Conservative movement, had wished).

Wertheimer also provides a long list of transdenominational educational enterprises of various sorts that have undoubtedly enjoyed great success, from Birthright Israel to Mechon Hadar to Limmud and others. His book’s conclusion sketches the outlines of “a large nationwide movement” consisting of “many hundreds of local synagogues, outreach centers, and start-ups engaged in the effort to remix Judaism for the current age.”

Wertheimer is ambivalent about much of what he has seen, but his very serious misgivings do not prevent him from being hopeful about the “next iteration of a new/old Judaism” in the United States. Having circulated very much less than he has (he lists the 160 rabbis to whom he spoke in preparation for this book and mentions the hundreds of synagogues he has visited over the years), I can’t really gainsay him. I can even hope that he is right. But when I weigh everything that I myself have witnessed together with all of the statistics signaling decline—Conservative Judaism has gone from representing more than 40 percent of American Jewry to less than 20 percent in a generation, 28 percent of those raised Reform have left the Jewish religion altogether, and so on—I can’t muster any comparable hope for the future of Judaism in America, except among the Orthodox.

Several years ago, I gave a talk to a group of students at Yeshiva University on cultural Zionism, in the course of which I expressed my doubts about the internal coherence of the project launched by Ahad Ha-Am (one of Horace Kallen’s sources of inspiration) at the turn of the 20th century. After our meeting was over, around 9 p.m. on a week night, my hosts walked me across the street from the building in which we had met to show me a little bit more of their institution. I don’t recall what I had been expecting, but I do remember my sense of astonishment when we entered a large, very crowded beit midrash (study hall). Unlike Moses, who was bewildered when God propelled him into the future to see the beit midrash of Rabbi Akiva, I knew what was going on. But I was nonetheless surprised to see hundreds of young men robustly and loudly engaged, in pairs, in the study of rabbinic texts when I myself was just about ready to go to bed. While I had been in batei midrash before, in the United States and in Israel, I had never witnessed a scene like this. Here, I thought (though I didn’t say it, perhaps because I felt that my hosts wanted to hear it), if anywhere, is a force capable of resisting the pressures of assimilation. I can think of nothing like it outside of the precincts of Orthodoxy.

Wertheimer both confirms my impressions and warns against drawing overhasty conclusions. “Thus far,” he writes, “the Modern Orthodox world has managed to flourish and persist by creating a community of practice and by focusing most of its intellectual energy on intensified Talmud study. This is not to be minimized. The movement’s vibrant communal life, high levels of observance, and serious engagement with traditional texts are monumental achievements.” But these achievements may not be as stable as they look. Roiled by challenges ranging from the heresies of modern biblical criticism to the appeal of ultra-Orthodoxy, Modern Orthodoxy is losing adherents to the left and to the right. Despite having a very low rate of intermarriage and a higher than average fertility rate, Modern Orthodoxy’s demographic growth just barely makes up for its losses. Haredi Jews now outnumber them two to one. Among school-aged children, the ratio in favor of the ultra-Orthodox has climbed to something more like four to one.

The ultra-Orthodox have their problems, too, but they’ve got the momentum, and they know it. There are now some six thousand to seven thousand haredi outreach workers in the field (mostly affiliated with Chabad but more than two thousand who aren’t). This is, Wertheimer informs us, “more than double the number of active Conservative, Reform, and all other permutations of liberal rabbis combined.” We, and especially the leaders of the liberal denominations, ought to let this extraordinary fact sink in, when thinking about the future of American Jewry. These outreach workers are not garnering many full-fledged recruits (the ba’al teshuvah phenomenon remains a countercultural trickle in comparison to the wave of assimilation). However, Wertheimer contends on the basis of extensive interviews, this is not their main goal. They would just like the rest of us to be, somehow, better Jews, and they’re largely succeeding at that. “Kiruv [outreach] has become a powerful vehicle for re-engaging Jews with the non-Orthodox sectors of the community.” Here too the elite meet the folk more or less where they are, but they also unabashedly represent a form of Judaism that demands much more than the Judaism of their liberal colleagues.

This is no doubt good for the Jews, but it doesn’t answer the question of how much of a future there is, in the long run, for nonharedi Judaism in the United States. On this matter, I can’t pretend to be among the optimists. I don’t want to admit that the game is over, though, even if the guys in the black uniforms do look like the team that will eventually win.

They certainly look a lot stronger than the team with which I have come to feel the greatest affinity: Jewish scholars who study their ancestors’ culture and history intensively but lack the faith that held them together. That’s in part because we’re not really a team at all but a relatively small and scattered bunch of people who tend to be more concerned with research agendas than our collective destiny as a minority. We might be closer than anybody else on the scene to what Horace Kallen hoped to see, but even if you add us together with all the ethnically conscious Jewish creative artists in this country, I don’t think we’re making much progress in, to put things in Kallen’s terms again, “the realization of the distinctive individuality” of our people. For the most part, we haven’t even tried.

As the more or less secular Jew I now am, I nevertheless agree with Jack Wertheimer that “aside from anti-Semitic persecution, nothing is likely to play a larger role in determining the future of Jewish life in this country than the lived religion of ordinary Jews.” But can one take one’s place alongside religious Jews just for this reason? People as different as Jay Lefkowitz, who was a senior policy adviser in the administration of George W. Bush, and Michael Walzer, the eminent left-wing political theorist, answer this question affirmatively. In his recent and much discussed Commentary article “The Rise of Social Orthodoxy,” Lefkowitz reconciles his theological uncertainty with his daily donning of tefillin, his kashrut, and his weekly synagogue attendance on the grounds that “the key to Jewish living is not our religious beliefs but our commitment to a set of practices and values that foster community and continuity.” Walzer, for his part, is no mere doubter but “a fully secular person,” one who is “theologically tone deaf” yet goes to his non-Orthodox “shul every Shabbos.”

You don’t have a Jewish life in Princeton, New Jersey, if you aren’t part of a synagogue. You don’t meet people that you want to talk to, the people that you can talk easily to about whatever awful thing has happened in the Middle East in the past week. I feel that’s a necessary part of my life, but it doesn’t make me a religious Jew. I cannot imagine a future for American Jews outside of the synagogue, and that means that secular Jews have got to find a way of connecting to the tradition.

It would be easy to admonish readers who want to help secure a Jewish future in the United States to follow in the footsteps of Lefkowitz, or at least of Walzer. I’m afraid, however, that I can’t preach what I can’t promise to practice (consistently, anyhow). But that doesn’t mean that I can’t try to clarify things. In my attempt to do so, I have drawn on the usual statistics that reflect the extent of defection from Judaism and Jewish life but also on the analyses of scholars like Biale and Magid who highlight the fact that the American melting pot is on the boil. What I do not share with my colleagues is the expectation that Zangwill’s “crucible” will somehow produce new human alloys who will be genuine and lasting heirs of the Jewish past, even if they might seem shockingly un-Jewish to us. What it produces, the rhetoric of contemporary identity politics notwithstanding, is good, more or less culturally homogeneous Americans.

Wertheimer’s account of current experiments with a “new/old Judaism” in liberal synagogues and elsewhere throughout the country is harder to dismiss, especially since he retains a keen awareness of their shortcomings even as he takes heart in their existence. Whether these are signs of a true revival of religious but non-Orthodox Judaism remains to be seen. If I’m skeptical about that, it’s not only on the basis of my own experience but because I can’t believe in the long-term survivability of any form of Judaism in our modern liberal democracy that isn’t rooted in solid convictions and consolidated by a disciplined and more or less segregated communal life.

The Modern Orthodox possess both of these things in good measure, and the ultra-Orthodox do so to an even larger degree, and will go on, for the most part, doing what they do. Some Jews who are much less rigorously religious may yet manage to sustain a strong presence on the scene, but it is undeniable that their overall numbers are shrinking. Those Jews who cannot quite say yes to God but cannot say no to Jewish peoplehood will fit, a little uncomfortably, into some of these communities, perhaps coming to shul infrequently and late, but, like Walzer, participating enthusiastically in the Jewish conversations at the kiddush. And the large majority of the rest of America’s Jews will in all likelihood (although not inevitably, as I must remind myself), like millions of their predecessors, disappear in the great American melting pot that continues to bubble away.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

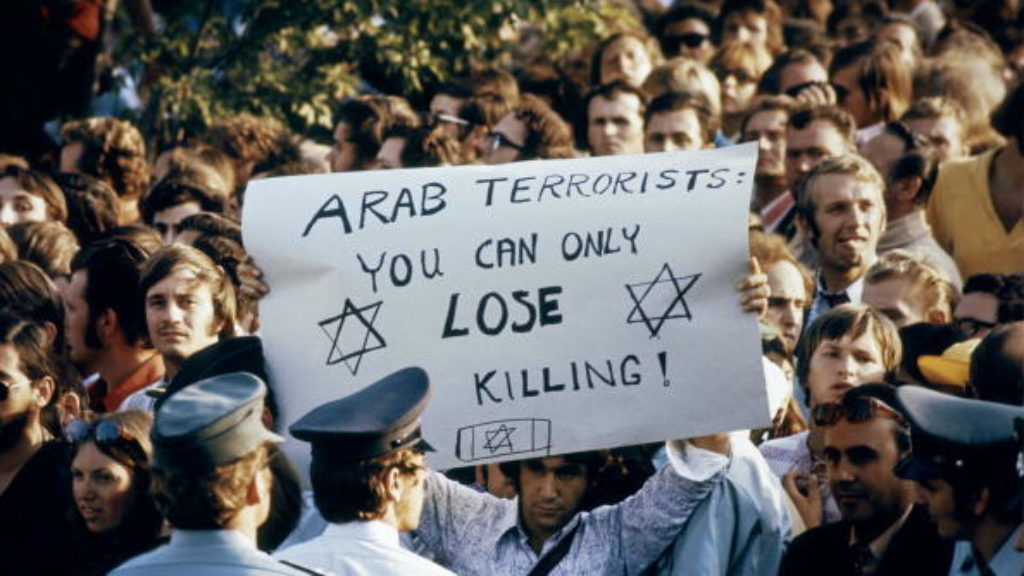

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

Beauty within Beauty: How Lag BaOmer Stopped a Plague

“One cannot, says Hasidism, have to do essentially with God if one does not have to do essentially with men.”

Some Calming Words

Hillel Halkin shouldn’t be so worried. Democracy is still alive and kicking in Israel. The Israelis who didn’t vote like him aren’t stupid. They’re no less wise, humanitarian, and upright…

Daniel Bell (1919-2011)

In memoriam.

goldish.1

Beautifully and cogently observed. This is the painful reality.

ashgerecht

Irrational paralysis should not accompany this rational analysis. Future-weighers might consider these two elements:

1. Increased welcome of prospective converts, both fro intermarried ranks and the general community, attractable to the Jewish concept of an incorporeal, abstract God and the exercise of free will from Adam on with accepted questioning and discussion.There are increased stirrings on this issue in both Conservative and Reform.The enlarging group of "nones"-religious but "spiritual" and disaffected Christians are available for take-a-look invitations.

2. Dropping the price bar. Jews and prospective Jews should be invited to the synagogue as a focus. (Tikkun olam today is the sacrifice of yesterday. The core of Judaism connects a concept of God to action.) Let seekers come in, then adjust staff to revenue instead of the present reverse.

Then take another look.

fsilber

"In the Melting Pot" suggested that Modern Orthodoxy had a successful approach to the fight against assimilation. From my place on the inside I see two weaknesses. One is that a good percentage of the children leave Modern Orthodoxy, becoming either Haredi or not-Orthodox at all. The other weakness is that educating each child requires, in today's money, about a half-million dollars. Physicians in the more lucrative specialties can afford it, as can businessmen who do at least as well. But most people cannot afford it.

I believe, however, that American Jews' assimilation rates are about to peak and go down, though the reason I believe this is not something to celebrate. I believe the next few decades will see a huge upsurge in antisemitism (where the word is taken to mean a general hostility towards most Jews for whatever reasons -- not necessarily race hatred). I see two sources of this increase.

One source is immigration. The Inquisition is a heritage of Latin Americans, and while they don't seem preoccupied with antisemitism at the moment, I don't think they have a horror of it. Furthermore, they probably view Jews as privileged European capitalists. As to the results of a large Islamic immigration, I don't think I need to say much.

The other source of antisemitism will be the Left. Just as racial antisemitism did not depend upon religious antisemitism but drew strength from it, the new antisemitism will be based on anti-zionism. For a Jew, the price of remaining in the Left is to ally oneself with and support those who chant "Death to the Jews" and who distribute candy in celebration when a Jewish child's head is blown off at point blank range. A Jew can gain acceptance by being OK with those who want to kill the 5 million Jews of Israel. (This reminds me of Jews in Germany who could earn a few days of freedom by helping the Nazi authorities catch other Jews.) Already they have made many major college campuses hostile environments for Jews, and a few decades from now it might be the entire Democratic Party. Most Jews will not want to seek refuge with the right, and may not have the option anyway if the antisemitic paleo-right gains a resurgence as is happening in eastern Europe.

So we may once again find ourselves socializing mainly with other Jews even if we're not religious -- for the same reasons that Jewish immigrants 100 to 140 years ago did so.