Letters, Fall 2011

The Novelties of Hank Greenberg

How fantastic, on your Summer 2011 cover, Moses Mendelssohn following the flight of a home run ball off Hank Greenberg’s bat! Only, your wonderful illustration of the fantastical would have been a little more realistic if Greenberg’s Detroit baseball jersey had only the number 5 on the back. When Greenberg was hitting homers, players didn’t have their names on their uniforms, and in the early days of the game there were not even numbers. Numbers were introduced in 1916 so that fans could match the players on the field with the numbers on their scorecards. It wasn’t until 1960, when television fans were without scorecards, that names appeared on baseball uniforms-first on the uniforms of the Chicago White Sox, in fact, when Hank Greenberg was sitting in the Chicago front office.

Tom Putnam

Buffalo, NY

In his perceptive review of Mark Kurlansky’s biography of Hank Greenberg, Eitan Kensky illuminates the aesthetic of Greenberg’s determined pursuit of excellence. For children of Jewish immigrants desperately yearning for American acceptance, Greenberg’s “baseball Judaism,” requiring (one-time) observance of Yom Kippur ten days after hitting two home runs on Rosh Hashanah, vicariously certified them as good Jews and loyal Americans. ThatHank also became the first major league player to be drafted into military service in 1941, re-enlisting the day after Pearl Harbor because “My country comes first,” added to his patriotic luster in the eyes of American Jews yearning to be Americans first.

Among the flaws in Kurlansky’s book not noted by Kensky is the astonishing omission of Greenberg’s most memorable and consequential hit: his pennant-winning, 9th-inning grand slam in 1945, not long after returning from five years of military service. I vividly remember my father pointing to newspaper photos of Greenberg joyously crossing home plate into the embrace of his teammates, and revealing: “Hank is our cousin.”

He was also a kind and generous man. A year after he retired he devoted an hour to hitting fly balls to his nephews and me, providing us with an unrivaled ascent to boyhood paradise. When I reached Oberlin College, Greenberg was general manager of the Cleveland Indians. I was a lonely freshman, and he graciously invited me to his home for Thanksgiving dinner. Then, every spring, he welcomed me to his private box in Municipal Stadium for dinner, genial conversation, and a game punctuated with his baseball insights. As superb a ballplayer and as powerful a symbol for American Jews as he was, Hank Greenberg was, above all, a mensch.

Jerold S. Auerbach

Newton, MA

Neo-Orthodoxy, or Non-Orthodoxy?

In his review of Irving Kristol’s new collection, The Neoconservative Persuasion, Meir Soloveichik pays close attention to a line that appeared in Kristol’s magisterial Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. In this line, which has haunted me since I first read it ten years ago, Kristol describes himself as “neo-Orthodox” in his “religious views”-“views” not “practice,” as he acknowledges not being religiously observant.

As a neo-Orthodox Jew, Kristol preferred the rabbinic tradition, with its reverence for the past and the promotion of religiously ordered lives, to the secular humanist version of Judaism, promoted by its more liberal adherents. He saw traditional religion as perhaps the only way to temper base human instincts in an open, free market society that not only allows, but actively promotes, morally problematic indulgences. Kristol’s neo-Orthodoxy thus contains an explicit socio-political aim.

While there is nothing wrong with this approach, it cannot be described as Jewish Orthodoxy, “neo” or otherwise. It is unclear why Soloveichik does not take Kristol to task on this. Orthodox Judaism requires committed observance of what it believes are divinely commanded laws. It shies away from overarching political theories of the kind that interest Kristol because the theory of Orthodox Judaism is that one should practice Orthodox Judaism, not just agree with it.

Kristol seems to have understood the rigidity of this approach, lamenting that before its great modernist (non-Orthodox) thinkers, Judaism did not have a viable intellectual dimension. Although overstating the case, Kristol taps into a central critique of Orthodox Judaism: that it is too rooted in narrow parochialism to speak to broad concerns. Soloveichik, while disputing Kristol’s conclusion, recognizes this is a challenge for Orthodoxy.

If one removes the “neo-Orthodox” label, Kristol advocates a vaguely positive view of religion as a “good thing,” without defining specific obligations to go with it; a warm and abstract reverence for tradition, with little interest in what that tradition requires; a belief that only the Jewish “moderns” can adequately address the “big” questions; and a conservative political agenda.

To me, this sounds like a right-wing version of Reform Judaism. Kristol’s approach is unique in its political orientation, but not in regard to ritual and practice. Those come from Reform Judaism’s theological approach that, as Kristol points out by way of criticism, often expresses itself through the promotion of political causes that are justified as being based on religious values.

One senses that Soloveichik understands this but is reluctant to say so. He would like to claim Kristol for Orthodoxy, but can’t quite get around Kristol’s lack of interest in halakha. What is disappointing is that Soloveichik makes such an effort to bring Kristol into the Orthodox camp while Orthodox Judaism more broadly has been so unwilling to engage with the ideas of non-Orthodox Jews who are nonetheless committed to Jewish tradition.

Judah Skoff

Hoboken, NJ

Meir Soloveichik Responds:

Judah Skoff queries how I can “claim Kristol” for Orthodox Judaism when Irving Kristol did not live the observant life of an Orthodox Jew. This would be an excellent question, were it not for the fact that nowhere in my article do I claim Kristol for Orthodox Judaism. What I stress is Kristol’s affinity, in his teaching and writing, for what he calls Burke’s “strong deference to tradition, which is the keystone of any orthodoxy.” It is this attitude that Kristol describes as “neo-Orthodox,” and it is from Kristol, I argue, that Orthodox Jews can learn a great deal about our own obligation to make this case to a larger audience-to become, as it were, the Burkes of the Jewish world.

It is therefore a profound mistake to refer to Kristol’s writings about religion and morality as a “right-wing version of Reform Judaism.” First, as I noted in my review, Kristol leveled his critique of non-Orthodox Judaism when he was a New Deal Democrat, long before he became “right wing.” But more importantly, in Reform Judaism’s emphasizing the moral autonomy of the individual over tradition, it advocates the very moral anthropology that Kristol critiques. With the Enlightenment, Kristol writes, much of the West changed its own attitude about the importance of the past, and with that, for many, came “a change that reshaped the very conception of what it means to be a ‘good Jew.'” Irving Kristol was certainly not an Orthodox Jew, but broadly speaking, in the battle of ideas within Western Civilization, Reform Judaism took the side of the Enlightenment, whereas Kristol sided squarely with Aristotle, Aquinas, Burke, and yes, Orthodox Judaism.

Judah Skoff concludes his letter with a strange attack on Jewish Orthodoxy, suggesting that Orthodox Jews show no interest in engaging “with the ideas of non-Orthodox Jews who are nonetheless committed to Jewish tradition.” I am not sure what he means by this. The great Orthodox Jewish thinkers of the 20th century were certainly not averse to studying the thought of Jews not affiliated with the Orthodox community. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, for example, studied and wrote about the philosophy of Hermann Cohen. Michael Wyschogrod was profoundly affected by his studies with Buber, and there are clear similarities between his theology and that of Franz Rosenzweig. I know of many young rabbis who have been profoundly inspired by the writings of Leon Kass. Orthodox Jews today certainly can, and do, learn from non-Orthodox thinkers, even as we at times criticize their denial of halakhic authority.

Letters to the editor may be sent to

[email protected].

Suggested Reading

It’s the End of the World as We Know It

Can liberal Judaism survive and thrive in the digital age?

A Tale of Two Synagogues

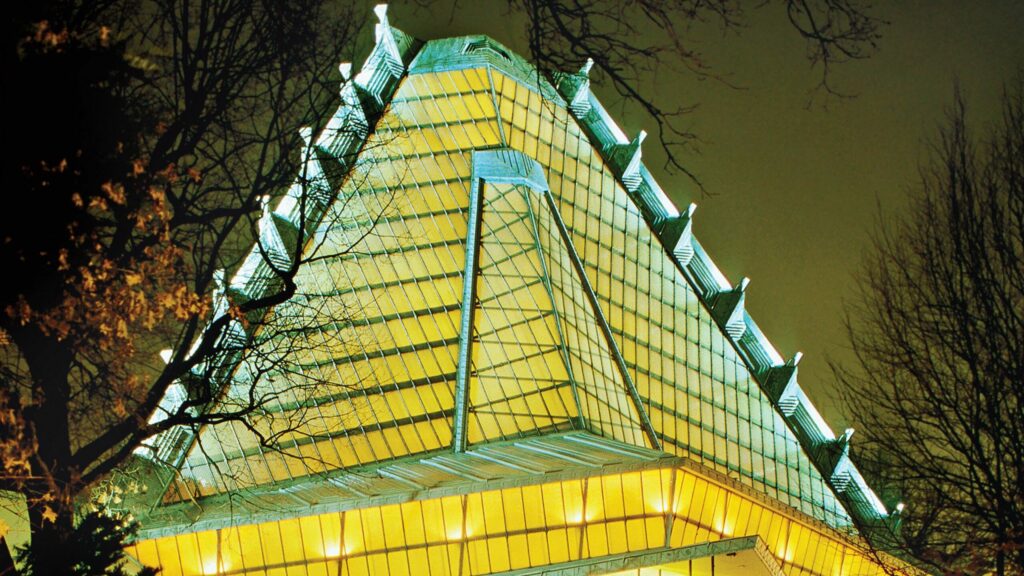

Frank Lloyd Wright built a dazzling temple outside Philadelphia. Too bad he didn’t look closely at the synagogue of Gwoździec, Poland, built two hundred years earlier.

One State?

Sari Nusseibeh's recent book is a new formulation of an old proposal.

A Walk in Jerusalem

Jews and Arabs live separately and are rarely friends, but they deal with each other constantly. The city can’t function otherwise. A walk in the Old City under a cloud of unease.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In