A Walk in Jerusalem

Much that is important in Jerusalem right now was visible during a short walk I took around the Old City on a rainy Tuesday in November: Four Border Police officers in riot gear, two men and two women, eyeing their smartphones and Arab passers-by with the same casual interest. Muslim women coming from the al-Aqsa Mosque, eyeing the officers. A blue-and-white flag on a wall declaring one apartment to be a Jewish island inside the Muslim Quarter. A gleaming Arabic sign announcing a new Israeli health clinic serving Palestinian clientele. Palestinian men at a traffic light outside the walls, crossing the invisible line between east and west Jerusalem on their way to work.

I waited at the light-rail stop outside Damascus Gate and boarded a train of Jewish and Arab passengers, fewer of both than usual. I got off downtown, and within an hour there had been a Palestinian stabbing attack on another train and a second attack at Damascus Gate.

The city of Jerusalem is subject to great and contradictory forces, some pulling its 830,000 residents apart and some pushing them together. The forces of disintegration have been evident in the spate of stabbing attacks against Israeli civilians and policemen this fall. In the six weeks beginning October 1 there were two dozen attacks or attempted attacks by Palestinians in Jerusalem alone, most involving knives. They persist, in Jerusalem and elsewhere, as I write. Jerusalem in crisis mode doesn’t resemble an American city during or after a race riot, for example, or a natural disaster. There aren’t burned-out neighborhoods or looted streets. There is no large-scale breakdown of public order. Instead there are small incidents of murderous violence, some localized rioting, and a cloud of unease.

At such times, which are familiar to those of us who have lived here for many years, pedestrian traffic thins out as people choose to stay home if they can. Kiosks and cafés notice this in their cash registers, and tourist cancellations hit the hotels. Car traffic worsens as parents drive their kids to school instead of sending them on public buses. Panicked reports make the rounds, summoned from the genuinely terrifying Middle Eastern ether and broadcast into our lives via Facebook and WhatsApp. Here’s one that pinged into my wife’s cellphone on October 13, passed on by another parent from our daughter’s kindergarten:

There is a warning that today Arab women will begin appearing in playgrounds in long, regular dress including a purse and sunglasses, ordinary camouflaged dress in order not to arouse suspicion.

Be careful of any male or female stranger that approaches you the female terrorists want to slaughter children with the knives in their purse!!!

That hardly seems plausible, but then neither does the idea that two schoolgirls would try to kill a grandfather with scissors, which is something that happened here not too long afterward.

Jews look nervously at any person who could be an Arab, meaning many if not most people in the city. Transactions among Jews and Arabs in stores and cabs are cautious and sometimes more polite than usual, as if to communicate: I am not a threat. Arabs are more aware of their vulnerability to harassment from Jewish hooligans—a regular feature of life for many Arab taxi drivers, for example—and are subject to the humiliation of police stops and searches. A feature of our our urban landscape: Young Palestinians in jeans and T-shirts, their lunches in plastic bags, waiting unhappily beside an armed woman their age as she looks at IDs and speaks into her radio, her back to them.

If Arabs can’t get into west Jerusalem, the city’s economy grinds to a halt. Nearly half of the workers in east Jerusalem make their living in the west. Palestinians also depend on the Israeli health system, which has been improving services in east Jerusalem, and the system in Jerusalem as a whole depends on Palestinian nurses, doctors, and hospital support staff. In the October 12 stabbing of a 13-year-old Jewish boy by two Palestinian cousins of about the same age, the Jewish victim was treated by Arab doctors and the surviving assailant was treated by Jews. This is common.

Jews and Arabs live separately and are rarely friends, but they deal with each other constantly, and the city can’t work any other way. More than any other single factor this mutual dependence “is what prevents the city from breaking down into a gang war, Belfast-style,” according to Marik Shtern, a geographer who tracks economic trends in the city at The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. A friend of his, a Jewish hotel manager, told Shtern that after the stabbing attacks began half of her Palestinian workers didn’t show up—they were too scared to come to west Jerusalem. She was scared of the half who did show up and conducted the hotel’s daily business with pepper spray hidden in her pocket. Unhappy, frightened, and aggrieved, the hotel continued to function, like the city itself.

On a day when two Israelis were stabbed at Ammunition Hill in northern Jerusalem, their assailant shot and wounded, I waited outside my kids’ elementary school in southern Jerusalem. I watched two boys in kippot holding the hands of an Arab minivan driver who was taking them home, as he does every day. When I arrived home a dozen city workers, most of them Palestinian, were replacing sewage lines on my street. Had I not heard the news, I wouldn’t have known anything was amiss.

The closeness of life here makes the perception gap between the sides even more striking. Among Palestinians the response to the stabbings seems to have been a curious mix of applause for the assailants and denial that they did anything wrong—they were, it was widely claimed, shot for no reason by police and then framed with planted knives. The dissonance reminded me of a 2002 rally in support of al-Qaeda that I attended as a reporter in London’s Trafalgar Square, where a friendly British-Pakistani guy my age told me he admired Osama Bin Laden for the 9/11 attacks and also that he suspected the Mossad was behind them.

Palestinian media, particularly (but not only) outlets controlled by Hamas in Gaza, have energetically called for further attacks, and if there was equally energetic condemnation from any Palestinian leader I missed it. Factions of Fatah, a movement generally referred to as “moderate” in Western news copy, tweeted enthusiastic encouragement. The Palestinians are part of the same Islamic world buffeted by some of the most disturbing ideological trends the world has seen since the 1940s—trends recently demonstrated on the streets of Paris—and in this context such violence makes sense. Our new neighbors from the Islamic State contributed a few videos expressing support and threatening worse. Helpful “how-to” stabbing guides were posted online. There seemed to be no awareness on the Palestinian side, at least publicly, of the way terrorism and their sympathy for it cripple those Israelis who seek coexistence, or the way it is certain to affect Palestinian livelihoods. The attackers haven’t been only young men but also women and children as young as 12, meaning that in Israeli eyes any Palestinian, no matter their age or gender, could be a killer. Given a choice, Jewish employers will thus reasonably prefer to hire Jews or foreign workers.

Some of the forces acting to destabilize the city, like the growing Middle Eastern weakness for nihilistic bloodshed and aversion to constructive politics, are not in Israel’s control. But others are. Our side is blind to the effect on Palestinians of Israeli actions, particularly on the Temple Mount and inside Palestinian neighborhoods. Not all Palestinian fears are baseless or the result of cynical incitement.

There has been no shift in government policy regarding Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount, but Palestinian Muslims have seen more religious Jews ascending and trying to pray there in recent years. The government ministers who support a more assertive Jewish presence on the mount do not represent the official line, but they aren’t figments of the Palestinian imagination. Neither is the small cadre of pyromaniacs who toy with the fantasy of replacing the Islamic holy sites with the third Temple. Most Israelis see these activists as marginal and their plans as harmless lunacy. But Palestinians don’t, and the fact that a group like The Temple Institute (“Build We Must”) has received hundreds of thousands of shekels in government funding makes Palestinian suspicions harder to dismiss.

Contrary to the most extreme of such suspicions, Israel has no plan to rid Jerusalem of its Arab population, whose growth rate is currently twice that of the Jewish population. But Palestinians see Jewish enclaves in neighborhoods like Silwan expanding, bringing with them more Israeli flags, friction, and armed guards with government salaries, invading the urban spaces where Palestinians feel at home and permanently changing them. More property changes hands every few months. This jeopardizes Israel’s claim to be a fair custodian and threatens to destabilize a place which is, after all, not a cosmic battleground but a real city whose well-being is a matter of life and death for the people who live in it.

Where is Jerusalem headed? The answer lies somewhere in that walk on a rainy day in November: In Israeli security officers trying to keep the peace; in the actions of some Jewish groups playing a dangerous game with Arab sensitivities; in a Palestinian public sympathetic to violence against Israelis but also drawn by what Israel has to offer; and in Israel’s ability and desire to give every resident of this abnormal city a chance at normal life.

Suggested Reading

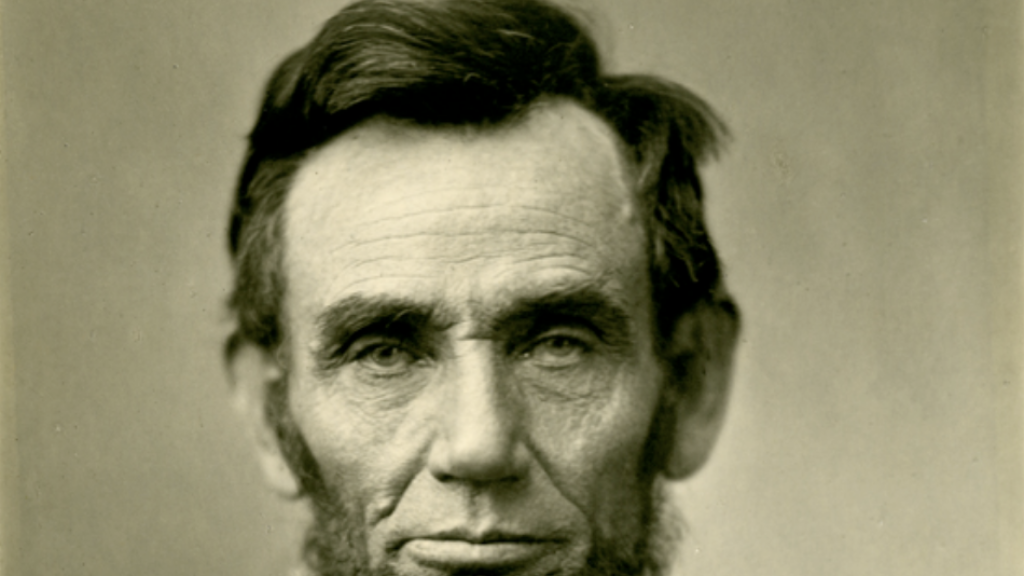

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

Pour Out Your Fury

When the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of books from monasteries in 1803, among them was an utterly unique haggadah.

The Zionavar Tapestry

Canadian fantasy writer Guy Gavriel Kay weaves unique novels with Jewish themes but never quite escapes Tolkien's orbit.

Something Antigonus Said

When the Saducees misinterpreted Antigonus of Sokho, they lost eternity--at least that's what the Rabbis thought.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In