Accounting for the Soul

Edith Brotman’s new book Mussar Yoga, with its cover photo of a woman in a graceful Tree Pose silhouetted against sea and sky, made me smile when it landed on my desk. Is this, I wondered, the asana for guilt? Because they never stinted on guilt, the old mussarniks. They also renounced Jewish mysticism, paid little attention to their bodies, and even less to other spiritual traditions. So Mussar Yoga makes for a surprising deli combo platter of the spirit, even in our easy-going mix-and-match America.

To be fair, Brotman is more or less aware of the incongruity. “If you are searching for a pure or traditional approach to Mussar or yoga,” she writes, “this is not the book for you.” And there is something to Brotman’s idea beyond feel-good American syncretism. The mussar movement attempted to inculcate ethical character traits through a regular practice of disciplined self-reflection, and yoga attempts to do something similar through the body.

In 1844 and 1845 Rabbi Israel Salanter, the founder of the mussar movement, had a publisher in Vilna reprint several works of Jewish ethics urging both students and laymen to set aside time to study them regularly and apply the lessons to their own lives. One of them was Cheshbon Ha-nefesh by Mendel Lefin. The title means, roughly, an “accounting for the soul,” and it offers a brilliant method for doing just that.

Lefin enumerated 13 basic virtues and asked the reader to associate each with a short saying or maxim upon which to concentrate. Lefin then instructed the reader to make a simple spreadsheet with the virtues running down the page (one for each week) and the days of the week across the top. So if the reader acted haughtily on, say, Tuesday of week 6, when he should have been concentrating on humility (anava), he put a black mark in that box. The 13 virtues (which could be customized) corresponded to the 13 weeks of a season, so that the reader concentrated on each virtue four times a year.

Cheshbon Ha-nefesh is Brotman’s principal model for Mussar Yoga. Her list of 13 virtues is somewhat different (notably missing is Lefin’s 13th virtue of perishut, literally “separateness,” roughly speaking, chastity), but the system is the same. Each virtue is now linked to a set of two or three yoga poses. In the place of maxims she introduces mantras that are as likely to derive from the Beatles (“All you need is love”) as the Bible (“Love your neighbor as yourself”).

Rabbi Salanter probably knew that Mendel Lefin was a modernist when he had Cheshbon Ha-nefesh reprinted, but he certainly didn’t know that the whole system—13 virtues/four yearly cycles, maxims, moral spreadsheets, and all—was secretly cribbed wholesale from Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. Franklin told his readers that he devised the system after having conceived “the bold and arduous Project of arriving at moral Perfection,” which, he cheerfully admitted turned out to have been harder than he thought. Nonetheless, it really was a brilliant scheme, the first best-selling American self-help system. In fact, there is now even an app for that “arduous project,” called Ben’s Virtues.

Max Weber famously saw Franklin’s system as a secularization of puritan introspection into capitalist productivity. If so, perhaps Salanter unconsciously returned it to its more natural home among the kind of strict pietists who, when faced with temptation, tried to envision the day of their deaths and the punishment that lay beyond.

Not everyone was convinced of the value of mussar. When Salanter’s disciple Rabbi Isaac Blazer tried to introduce it into the curriculum of the great yeshiva of Volozhin, Rabbi Hayyim of Brisk rejected the suggestion out of hand. In the account of his grandson, Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik, he replied:

If a person is sick, we prescribe castor oil for him. . . . [But] if a healthy person ingests castor oil he will become very sick . . . [I]f you are spiritually sick . . . then you must use more powerful drugs . . . the remembrance of the day of death. We in Volozhin, thank God, are healthy . . . If the scholars of Kelm and Kovno feel compelled . . . let them drink to their hearts content, but let them not invite others to dine with them.

One can only imagine the Brisker’s response to Mussar Yoga, or, for that matter, the response of the mussarniks of Kelm and Kovno. But Ben Franklin probably wouldn’t have minded.

On the few occasions when I have gone to a yoga class, I’ve left feeling alert, relaxed, and refreshed—in short good. I’ve sometimes even had the heretical thought “why don’t I feel this good after shul?” After all, the Shema is a meditation and the Amida is a carefully choreographed prayer (three steps forward, three steps back, the necessary bows, the optional swaying). Of course, the problem may be—in fact, certainly is—me. I remember my own brief time in a mussar yeshiva and the elegant intensity with which one particular student would pray, his back ramrod straight, his hands eloquently beseeching. And then, also, the old mussar voice comes back to me: “Who said you were supposed to feel good?”

The Brisker Rav may have been right to reject mussar for Volozhin and Ms. Brotman may be correct in diluting it for her readers now (though when one sees a headline like “I love me” one may wonder how much is left), but it did produce some truly saintly personalities. The main stories about Rabbi Salanter are not about his talmudic genius or his ritual piety but rather the extraordinary care he took in ordinary interactions: the time he missed Kol Nidre to take care of a stranger’s crying baby, the lengths he took to avoid embarrassing recipients of charity, the afternoon he spent trying to lead a lost cow back to its farm, and so on.

Last Shabbat, I was playing with my six-year-old daughter Bayla and we started flipping through Mussar Yoga. We tried Up Dog, Down Dog, the Boat Pose (a kind of open-armed crunch Brotman places under Generosity), Reverse Warrior (Humility), and a couple of others. Incidentally, it turns out that the sun salutation exercise, the most common sequence in contemporary yoga, is even more recent than Franklin’s Autobiography, a 20th-century invention, as I learned from “Yoga: The Art of Transformation,” an extraordinary museum exhibit that I saw in its Cleveland incarnation. Anyway, eventually I pulled something and had to rest in Savasana, the lying-down—literally “corpse”—pose.

Lying there on my family-room carpet, I remembered the story of Rabbi Salanter’s death. He was living alone in Koenigsberg, sick and very poor. Some of his students paid an elderly attendant to stay with him overnight. When they came the next morning, he had passed away. They asked what his last words had been. The attendant said that Rabbi Israel had spent the night reassuring him that the body of a man was harmless, and that there was nothing to worry about in being alone with a corpse.

Suggested Reading

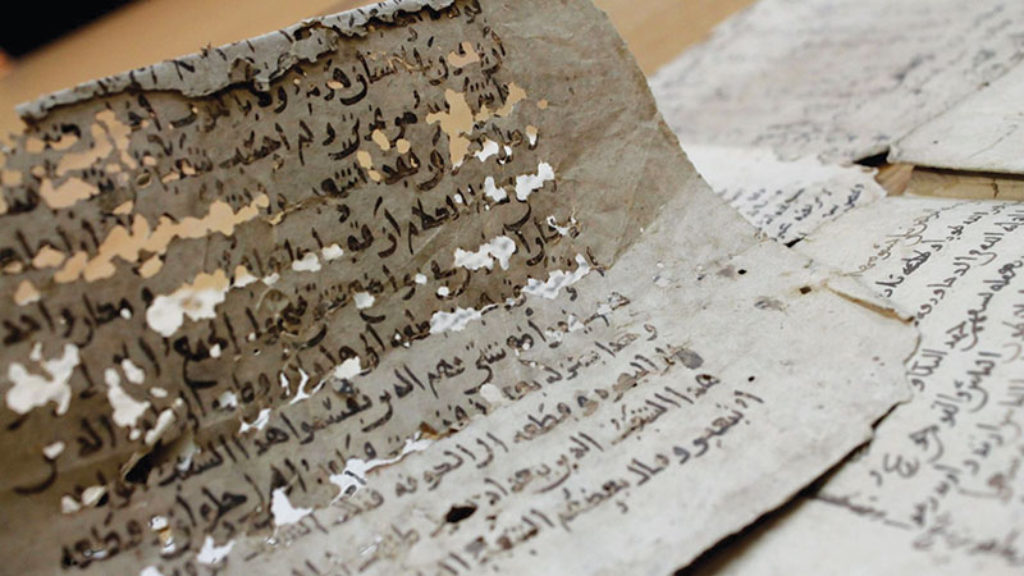

Afghan Treasure

Sometime in the 11th century, a distraught, young Jewish Afghan man named Yair sent a painful letter to his brother-in-law. Life had dealt Yair a tough hand, or maybe it was just his own bad choices.

The First Lady of Zionism

At the age when most of us are just about to fold our tents, Henrietta Szold, pitched hers—and in the Holy Land, no less.

Lost Music

Jeffrey M. Green, Aharon Appelfeld’s translator for more than 30 years, remembers the beloved Israeli novelist.

Friendly Fire: A Response and Rejoinder

Peter Berkowitz responds to Jeremy Rabkin.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In