The First Lady of Zionism

Writing a biography—conjuring a life—is a lot like being a magician. Both ventures call for a keen sense of pacing, a trusting audience, illusion, sleight of hand, the occasional incantation, and behold: a person! (Or a rabbit.)

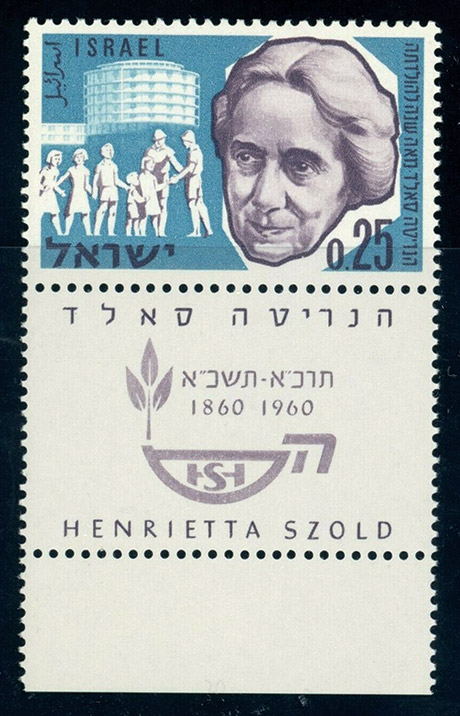

Dvora Hacohen’s commanding account of Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah, the preeminent Zionist women’s organization, and Youth Aliyah, the rescue and resettlement agency for Jewish children of the war years, is no confidence trick, that’s for sure. Years in the making (and originally published in Hebrew), it draws on a wealth of sources, among them Szold’s extensive diary entries and equally extensive correspondence, especially with her many sisters, to bring the talented Miss Szold—once a household name—back into circulation. Hacohen, a professor of modern Jewish history at Bar-Ilan University and a recipient of the Ben-Gurion Prize, renders her subject a full-bodied personality rather than a figurehead: a “human woman,” as Szold herself once put it, which is where the magic comes into play.

Born in Baltimore in 1860 to Sophie and Benjamin Szold, Hungarian immigrants who relocated from the Old World to the New to take up positions as rabbi and rebbetzin, respectively, at Congregation Oheb Shalom, Henrietta grew up in a lively German-speaking household. The eldest of eight siblings, all of them girls, Henrietta and her sisters were exposed at home to the richness of Jewish culture as well as the challenges and possibilities of Jewish communal service.

Szold took to the life of the mind with particular avidity, excelling in her studies at Misses Adams’ School for Girls, where she later became a teacher, and prompting her to enroll in classes in Aramaic, Talmud, and ancient Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1904 when she was already in her early forties—the very first woman permitted to study in its hallowed halls. Solomon Schechter, the institution’s president and a family friend, had advocated on Szold’s behalf, reassuring the trustees that her intentions were personal rather than professional.

Szold’s intellectual chops were matched by her equally pronounced concern for the well-being of others, inspiring her to establish a night school in Baltimore, where recently arrived Russian immigrants of the 1890s were taught English and vocational skills such as bookkeeping and dressmaking. An avid Zionist at a time when committed American Zionists were few and far between, Szold drew on her logistical talents and visionary ideas about Jewish social service to found Hadassah twenty years later, in 1912. As much an exercise in female empowerment as an expression of charitable uplift, the organization transformed Zionism from a cause into a calling.

Szold’s adaptability, her nimble genius, might well be credited to her having had an early start. She began her professional career at the age of seventeen while a cub reporter for the Jewish Messenger, a New York weekly. Going by the name of Sulamith, she happened to be on the scene and at the table in July 1883 when the drama of the “Trefa Banquet” unfolded in Cincinnati. “There was no regard paid to our dietary laws,” the kosher-keeping eyewitness related of the celebratory communal dinner marking the graduation of the very first class of Reform rabbis in the United States. Worse still, when she and several of her tablemates refrained from eating the forbidden bill of fare, awash in seafood, “We were . . . stared at as if we were mummies or fossil remains.”

Szold went on to serve as secretary for the fledgling Jewish Publication Society, where her thankless remit encompassed editing, translating, and proofreading. “I had to go to the printing office to give the foreman a blowing up,” Szold recalled after one particularly vexing encounter. “Some wrongly stupid commas have gotten mixed up with the others, and [it] was four hours today picking them out of some 40–60 pages of proof. My eyes feel queer after that hunt.” Concomitantly, she added to her considerable workload, which kept her up until the wee hours of the morning, by assuming similar responsibilities for two of American Jewry’s most significant cultural undertakings, the American Jewish Year Book and the Jewish Encyclopedia.

For years, Szold furnished others with the opportunity to shine while her prospects—and eyesight—dimmed. Most of the time, she accepted this unfair state of affairs graciously and resignedly: her portion in life as an overeducated, unmarried, bourgeois American Jewish woman with few financial resources. Now and again, though, Szold would write in her diary of how she wouldn’t mind being acknowledged, much less thanked, for her considerable efforts on behalf of so many others.

Language energized Szold’s life; it also led to her undoing, giving rise to one of, if not the, most unsettling periods of her life, the years between 1908 and 1912. While translating, editing, and readying the multivolume Legends of the Jews for publication, Szold and her author, Louis Ginzberg, a distinguished young Talmud scholar at the Jewish Theological Seminary, bonded over words, or so she thought. Though he was thirty-four and she thirteen years his senior, Szold fell hard for him, mistaking the “Dear Henrietta,” with which some of his letters to her began, as a term of endearment rather than an epistolary convention and, after the letters turned more personal, dreamily imagining a life together. Whether Ginzberg was obtuse and tone deaf or purposefully toyed with Szold’s emotions is left for the reader to decide.

When Ginzberg oh-so-casually (read cruelly) informed Szold that he was engaged to marry someone else, the twenty-three-year-old Adele Katzenstein of Berlin, her world fell apart. She collapsed into a pummeling depression that lasted for many years—far longer than most historians were aware of until now. Hacohen makes much of Szold’s emotional crisis, quoting judiciously and sensitively from her diary entries. They are shattering. “Today it is four weeks since my only real happiness in life was killed by a single word. . . . There has been only suffering, nights and days, and days and nights of suffering,” Szold wrote poignantly while the wounds were still fresh. Two years later, she related in another diary entry, “Not only has he [Ginzberg] ruined my life, he has ruined me. Did I ever envy before?—This morning I am like a burnt out crater, headache, shame, and lassitude.”

Hacohen’s focus on Szold’s unraveling not only uncovers her subject’s humanity but also frames the balance of the narrative by suggesting that it, even more than the founding of Hadassah, was the precipitating factor in Szold’s subsequent decision to shift gears dramatically and, in 1920, to light out for Palestine, whose destiny and hers would be henceforth intertwined. “What I discovered,” Szold’s biographer tells us, “was a life divided into two distinct parts, so different from each other as to appear to belong to two different people.”

At the age when most of us are just about to fold our tents, Szold, pitched hers—and in the Holy Land, no less. With a seemingly inexhaustible supply of energy that belied her years, she gave her all—and then some—to improving the well-being of the Yishuv’s residents in the years following the Great War. Forming the “American Daughters of Zion, Nurses Settlement” in Jerusalem, a neighborhood clinic that took its cue from the Henry Street Settlement in New York, and establishing the Hadassah Medical Organization, replete with a nursing school, ambulances, and the latest technology, including x-ray machines, she did battle with the many diseases and ineffectual Old World remedies that afflicted the local population.

Never one to turn down an assignment or, for that matter, to miss a meeting—“Palestine is as meeting-beridden as the United States,” she once complained—Szold also served on the Yishuv’s Jewish National Council, where she juggled the demanding education and health portfolios. And then, in what would turn out to be the apex of her career, she created the Youth Aliyah organization in response to the worsening crisis in Europe, rescuing thousands of Jewish children, many of them soon to be orphans, by resettling them in specially designed settlements. As Szold looked back at what she had wrought, she was right to say that “it seems to me I have lived not one life but several, each one bearing its own character and insignia.”

Trying to keep up with Szold’s many lives, Hacohen’s narrative quickens its pace and takes us along for the ride—on bumpy roads atop a mule in the Galilee; on a slowpoke train that ran from Jaffa to Jerusalem; restlessly pacing the deck of a steamer to and from the US, the United Kingdom, or France—wherever Szold went, hat in hand, in search of the funds with which to keep her various enterprises afloat. “For me apparently there will be no salvation but to live on the ocean,” she remarked while preparing to embark on yet another adventure on the high seas.

Geography isn’t the only thing that presses in on and envelops the book’s subject as well as its readers. So, too, does the larger context in which Szold’s biography is set and against which her storied life unfolds: World War I, illness, the deaths of beloved family members and friends, the rise of Nazism, riots in Palestine, internecine squabbles within the Zionist movement, the intransigence of the British. Virginia Woolf once famously observed that a biographer must take into account both the subject and her environment: a “fish in a stream,” as the British writer put it. Within these pages, that stream takes the form of a fast-moving current, dangerous eddies of water threatening to drown its subject.

Nothing if not tenacious, Szold held on for dear life. Looking more like someone’s grandmother than the formidable powerhouse she was, she withstood a cascade of challenges that would have sent a less resolute person back to bed at home in the States. Not that she wasn’t tempted. “I was ready to flee back to America,” this indefatigable communal servant wrote after a particularly trying period when tension between the skilled medical personnel she had imported and the hidebound community they sought to serve ran unusually high. “I wondered bitterly whether I had devoted twenty years of my life to an ideal that had turned out to be a will-o’-the-wisp.”

She stayed the course, becoming a familiar figure throughout Mandatory Palestine: a perky hat on her head (black felt in winter, straw in summer), a pair of sensible shoes on her feet, and a sturdy handbag affixed to her arm—the very picture of a no-nonsense woman. Though from time to time, Szold would confess to a hankering for pretty things—“I long for gracious living”—for most of her life she did without, her day-to-day existence austere, even spartan. By the time of her death in 1945, Szold had few possessions to her celebrated name.

For all the marvelous details that this volume amasses, I missed learning more about Szold’s interior landscape, which is out of sight for most of its three-hundred-plus pages. Yes, it is on display, and painfully so, during Hacohen’s recounting of the Ginzberg imbroglio, but, as one year in the Holy Land gives way to another and then another, little of it surfaces. It is hard to tell whether Szold herself decided to shelve her emotions and to “seal myself up,” as she put it in her diary, or whether that was the author’s decision: a protective gesture, a way to shield Szold from further harm.

We don’t encounter much of an authorial voice either. Hacohen prefers to let the swirling events that inhabit her text speak for themselves. She is sparing, too, in her use of adjectives, even when paraphrasing her subject’s most vivid accounts. I understand not wanting to look like a ventriloquist, but Szold was so marvelous a writer that it seems remiss not to let readers encounter her voice unfiltered. When her words are quoted, they sing on the page. Here she is, rhapsodizing over the landscape of the promised land:

The land is treeless, largely waterless, at this season the green has largely disappeared, and the dry thornbushes almost crackle under the hot sun—and yet it is beautiful, so beautiful that I almost resent our intention to make it blossom and bear fruit. The stones are soft with colorfulness and between them spring up blossoms so curiously adapted to the peculiarity of the land that one cannot wonder enough.

That the natural order inspired Szold’s writerly gifts should come as no surprise. An abiding interest in things that grew was the one constant in her peripatetic, often unanchored life—apart, that is, from her family and her widespread circle of friends. It was also of a piece with her tending to the lives of others. A member of the Baltimore Botanical Club, she once delivered a paper on the “growth, mechanics of, tensions and mutations of plants.” Mother Nature caught her eye back then and stayed with her, the “mother of all the children . . . everyone’s mother,” through thick and thin, endowing Szold’s life with an amplitude all its own.

Sitting in her lovely Jerusalem garden, a cup of tea and a plate of freshly baked cookies at the ready, the air thick with chatter, Szold was at her most resolved. “I lived a rich life,” she confided in a friend, “but not a happy life.”

Suggested Reading

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

Politics and Prophecy

Ari Shavit, the Israeli prophet-journalist, offers both rebuke of the past and warnings for the future, but unlike prophets of old, he has no solutions for the way forward.

Promised Land or Homeland?

The university presses of Cambridge and Oxford have released two new works of Jewish political theory that blend theoretical defenses of Zionism with robust critique of what Chaim Gans calls the “Zionist mainstream.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In