The Abrams Case and Justice Holmes’ Philo-Semitism

In 1919 Oliver Wendell Holmes changed his mind and in so doing transformed the law of free speech. Before his famous dissenting opinion in Abrams v. United States, the Supreme Court justice had shown little interest in a speech-protective approach to the First Amendment. That same year Holmes had authored a trilogy of unanimous decisions for the Court upholding the criminal convictions of Philadelphia socialist Charles Schenck, Missouri newspaper publisher Jacob Frohwerk, and perennial Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs for protesting America’s involvement in World War I. This was in line with the abiding tenet of Holmes’ overall constitutional philosophy: a fatalistic (some say nihilistic) deference to the prerogatives of the democratic majority, no matter how wrong-headed the majority might be.

When Abrams came before the Court in the fall of 1919, it would have been reasonable to expect Holmes to view the case through the same lens. The defendants were five Russian-born Jewish anarchists prosecuted for distributing leaflets in New York City (both in English and in Yiddish) urging workers’ strikes at munitions factories. Targeted at the Wilson administration’s opposition to the new Bolshevik government in Russia, the leaflets nonetheless were distributed while the United States was at war with Germany and were deemed a potential interference with the war effort. In Red Scare, post-armistice America, the Abrams defendants could expect little sympathy in the courts. A 7-2 majority of the Supreme Court showed them none, affirming their convictions and rejecting their First Amendment arguments on the strength of Holmes’ reasoning in the Schenck, Frohwerk, and Debs cases.

Yet Holmes himself—joined by Justice Louis Brandeis—disagreed. “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical,” the seminal passage of Holmes’ dissent began. “But,” it continued, “when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths”—in other words, that the persecutors are often proven wrong—“they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” Ultimately (as if to prove the validity of its own major premise), Holmes’ dissenting opinion won acceptance in the marketplace of legal ideas and came to represent the majority view of the Supreme Court.

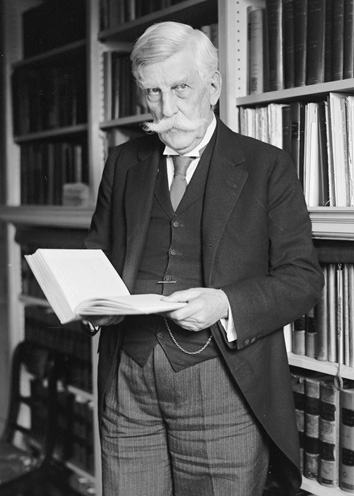

Why Holmes changed his mind has long been a source of fascination and puzzlement for legal scholars. In The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind—and Changed the History of Free Speech in America Thomas Healy, a professor at Seton Hall University School of Law and former journalist, has given us a highly readable and thought-provoking account of this important moment in American constitutional history. Like scholars before him, Healy draws heavily on Holmes’ contemporaneous correspondence with several progressive intellectuals who, as prosecutions of wartime protestors mounted, sought to move Holmes toward a more liberal position on free speech. Prominent among these was the British- Jewish political scientist Harold Laski, then only in his mid-20s and teaching at Harvard. (Laski would go on to briefly chair the Labour Party after World War II and clash with Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin over the latter’s anti-Zionist Palestine policy.) It was at Laski’s suggestion that Holmes read a new biography of Adam Smith and re-read John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. These works, according to Healy, inspired the intellectual rationale of the Abrams dissent and in particular the now-familiar metaphor of a marketplace of ideas where free speech facilitates the discovery of truth, much like free trade facilitates growth in economic markets.

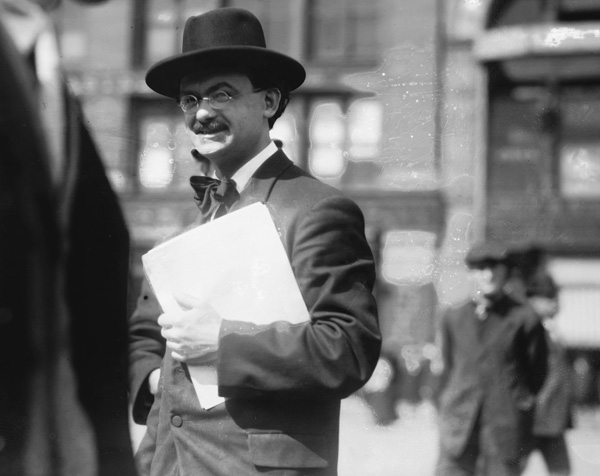

Yet in Professor Healy’s retelling, Holmes’ transformation was as much a change of heart as a change of mind, and for that Laski bears even greater responsibility. The decisive factor in that transformation, Healy suggests, was a campaign to banish Laski from Harvard for his left-wing views. In the fall of 1919, Laski created an uproar by vocally supporting an unpopular strike by the Boston police force. Denunciations from the press, the Boston establishment, and wealthy Harvard alumni followed, along with calls that Laski be fired. A few days before Abrams was decided, Laski asked Holmes if he would write an article on toleration for The Atlantic Monthly, which would aid Laski’s defense. That request was made at the suggestion of future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, another Jewish Holmes acolyte then teaching at Harvard.

While Holmes did not share Laski’s political views, he had grown extremely fond of him personally. The two summered near one another on the North Shore of Boston, and Holmes took “the greatest pleasure” in Laski’s conversation. As well he might: Immensely learned and extraordinarily agreeable, Laski displayed, as Edmund Wilson once observed, a “genuine emotion of piety” towards Holmes, some 52 years his senior. For both the childless Holmes and the non-observant Laski, estranged from his own Orthodox father, their association took on the psychological dynamics of a father-son relationship. Healy hypothesizes that empathy for Laski, “the son [Holmes] never had,” is what finally pushed Holmes into the pro–free speech camp:

For what had been merely an abstract question for Holmes over the past year was, suddenly, concrete and personal. The face of free speech was no longer Eugene Debs, the dangerous socialist agitator. It was his good friend Harold Laski, and Holmes’s views shifted accordingly—and dramatically.

Holmes never wrote the article for The Atlantic Monthly. But Healy contends that he wrote his Abrams dissent as a kind of substitute. Contemporaneous evidence from Holmes supports that contention. In a November 1, 1919 letter to Frankfurter, Holmes explained that although he was “too busy” to write the proposed article, “Just now I am full of a tentative statement that may see light later on kindred themes to your subject.” In fact, he had just completed his Abrams dissent and sent it off to the printer.

Healy’s insight gives rise to an intriguing question that Healy touches upon but does not directly explore. As Healy notes, anti-Semitism was “prevalent” at Harvard at the time, and it was perceived as a motivating force behind the anti-Laski campaign, as well as a similar campaign in the spring of 1919 to banish Frankfurter for his supposedly radical views, as well as an attempt that year to oust yet a third Jewish professor, philosopher Harry Sheffer. (There were only five Jews on the entire Harvard faculty at the time.) When Laski was nominated for membership in the Harvard Club in early 1919, the membership committee deemed it necessary to conduct further due diligence on him because, as the club secretary explained in a letter, “Mr. Laski is a Jew.”

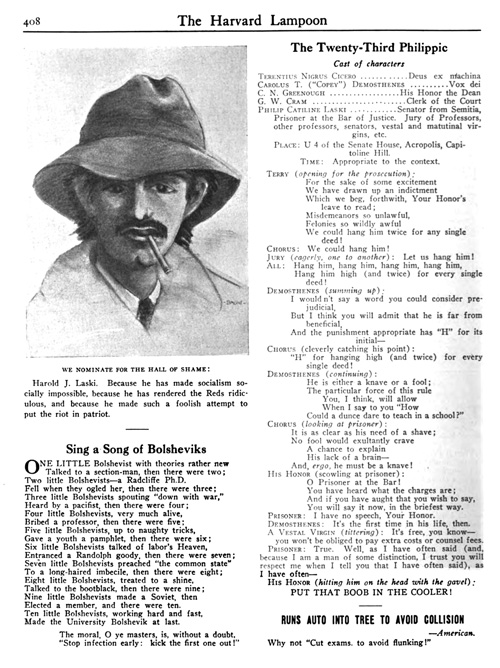

During the police strike firestorm, one alumnus told Harvard President A. Lawrence Lovell (himself known to harbor anti-Jewish sentiments) that if a “Russian Jew” and “out-and-out Bolshevik” like Laski remained on the faculty, he would refuse to contribute to the university’s endowment campaign. And in January 1920, The Harvard Lampoon devoted an entire issue to vilifying Laski in 16 pages of anti-Semitic “poems, plays, cartoons, songs, and articles” mocking him as “Professor Moses Smartelickoff.” A few months later Laski resigned from Harvard and returned to England, confiding in Bertrand Russell that he was “heartily sick of America” and eager to be in a land “where an ox does not tread upon the tongue.”

Could Holmes’ reaction to anti-Semitism have played some role in his historic shift in Abrams? If, as Healy posits, Laski became the “face of free speech” for Holmes when writing his dissent, it follows that the face of repression hovering in Holmes’ subconscious may have been the anti-Semitism that sought to silence Laski (as well as Frankfurter). And if so, this might help explain why Holmes viewed Laski’s plight, and that of the Abrams defendants, differently than the seemingly similarly situated dissenters in Schenck, Frohwerk, and Debs. Certainly Holmes was aware of the anti-Jewish prejudice directed at his two young Harvard friends. In an April 5, 1919 letter, Holmes asked English legal scholar Frederick Pollock if he knew Laski, adding: “People in Boston seem to have got the idea that he is a dangerous man (they used to think me one) . . . There is also a prejudice against Frankfurter; I think partly because he (as well as Laski) is a Jew.” As for himself, Holmes told Pollock: “It never occurs to me until after the event that a man I like is a Jew, nor do I care, when I realize it.” That same month Holmes asked Laski why he and Frankfurter were encountering such opposition, and Laski replied by relaying a colleague’s view that, at least in Frankfurter’s case, “it is antisemitism.”

Historians have often noted that Holmes did not share the anti-Semitism common in his day. To the contrary, he formed friendships with many Jewish intellectuals for whom, according to Edmund Wilson, he “felt a special affinity”: not only Laski and Frankfurter but also Brandeis, the philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen, the journalist Walter Lippmann, and the diplomat Lewis Einstein. “When I think of how many of the younger men that have warmed my heart have been Jews,” Holmes once told Laski, “I cannot but suspect” that “loveableness is a characteristic of the better class of Jews.”

This was an era when an avowed anti-Semite, James McReynolds, could sit on the Supreme Court and refuse to talk to (or even be photographed with) another justice, Brandeis, simply because Brandeis was a Jew. By contrast Holmes welcomed Brandeis and his “hopeful attitude toward the future that seems characteristic of his race,” and the two men went on to form one of the Court’s most historically significant collaborations. “To me it is queer to see the wide-spread prejudice against the Jews,” Holmes once remarked to Pollock while praising Brandeis. “I never think of the nationality and might even get thick with a man before noticing that he is a Hebrew.”

Holmes’ philo-Semitism is something of a curiosity. As a Boston Brahmin, Holmes might have been expected to share the anti-Jewish prejudices of his social class. Holmes’ grandfather advocated converting Jews to Christianity. Holmes’ father, himself a famous physician and popular writer, admitted growing up “inheriting the traditional idea that [the Jews] were a race lying under a curse for their obstinacy in refusing the gospel” and “shar[ing] more or less the prevailing prejudices against the persecuted race.” (Later in life, Holmes’ father experienced an epiphany while seated between two Jews at the theater and became a proponent of religious toleration.)Even Holmes’ wife of more than five decades, Fanny, disagreed with him on the subject of Jews: “‘She calls them Keiks and how can I bother with them,’” a friend once recalled Holmes saying, “‘but I never notice their noses, it’s their conversation I like!!!’”

Holmes, whose views of human nature were shaped by the brutality of his Civil War experiences, was also deeply influenced by Social Darwinism. “The real Holmes,” as he was unkindly judged by the late Yale law professor Grant Gilmore, “was savage, harsh, and cruel, a bitter and lifelong pessimist who saw in the course of human life nothing but a continuing struggle in which the rich and powerful impose their will on the poor and weak.” Black causes did not fare particularly well before Holmes, who voted repeatedly to uphold segregationist legislation. Yet Holmes, himself agnostic in matters of religion, seemed to treat Jews as equals and react adversely to discrimination against them.

Four years before Abrams, Holmes had stood up for Leo Frank, the unfortunate Jewish Atlanta factory manager falsely accused of murdering a 13-year-old girl and convicted at a trial conducted in the shadow of an angry anti-Semitic mob. A majority of the Supreme Court refused to entertain Frank’s application for habeas corpus relief. Dissenting (this time joined only by Justice Charles Evans Hughes—Brandeis was not yet on the court), Holmes decried Frank’s conviction as the product of “the passions of the mob” and “lynch law.” (Shortly thereafter Frank was, in fact, lynched after Georgia’s governor commuted his death sentence.) In correspondence, Holmes described his opinion as “a dissent as to which I feel a good deal” and characterized Frank as “a Jew convicted of murder in Georgia after a trial that we thought a farce.”

The Abrams defendants were also Jewish (although, like Laski, non-observant), and anti-Semitism infected their case as well. Although their trial took place in federal court in Manhattan, the presiding judge was a pinch-hitter from down South, Henry DeLamar Clayton, Jr., brought in to help out with a case backlog. An “Alabama bigot” and “apologist for slavery” as described by Healy, Clayton could not conceal his contempt for the cadre of Jewish revolutionaries before him, who had arrived from Russia only a few years earlier. When Jacob Abrams, testifying in his distinct Yiddish accent, referred to “our forefathers of the American Revolution,” Clayton, a fifth-generation American, immediately cut him off. “Your what?” he asked incredulously. “Do you mean to refer to the fathers of this nation as your forefathers?” Annoyed at defense lawyer Harry Weinberger’s persistence in a line of questioning, Clayton ordered him to sit down, complaining “the Lord knows I can not out-talk a Jew.” At sentencing, Clayton contrasted the defendants with “our good, free American Jewish citizens” who understood the virtues of capitalism, offering the irrelevant aside that previously “the Irish had all of the offices and the Jews had the money,” but now Jews “actually have taken some of the offices away from the Irish.” Clayton sentenced Abrams and two of his co-defendants to the maximum prison term of 20 years.

In his Abrams dissent, Holmes went out of his way to criticize Clayton’s sentences, which, as Healy notes, were not even at issue before the Court. Even if properly convicted, Holmes wrote, “these poor and puny anonymities” were deserving of only “the most nominal punishment.” The harsh sentences effectively made the defendants “suffer not for what the indictment alleges but for the creed they avow”—a creed that “no one has a right even to consider in dealing with the charges before the Court.” Holmes’ insistence that the defendants’ “creed”—what they thought and believed—was strictly off limits (“no one has a right even to consider” it) is a powerful expression of the principle of toleration. Although Holmes was apparently referring to the defendants’ political “creed,” there is an obvious parallel to be drawn with Holmes’ religion-blind approach in dealing with Jews, which likewise gave no consideration to their religious “creed.”

Legal scholars have long struggled to make sense of Holmes’ Abrams dissent, both because of its seeming inconsistency with Holmes’ prior free speech opinions and because of its doctrinal incoherence. The opinion advances a quintessential liberal humanist goal—toleration for the opinions of others—while seeming to lack a liberal humanist soul. Rather than proclaim any individual right to self-expression, Holmes instead emphasized the societal interest in promoting the search for truth in a marketplace of ideas. Given Holmes’ abhorrence of natural law doctrines centered on individual rights, that is not surprising. But it is hard to square with Holmes’ longtime pragmatic epistemological stance, which held that “truth” comprises nothing more than what the dominant majority believes.

For all its philosophical abstraction, the Abrams dissent radiates an undercurrent of empathy. Holmes himself probably would have denied that. But he too sensed that his stated reasoning was incomplete, acknowledging in the last sentence of the dissent: “I regret that I cannot put into more impressive words my belief that in their conviction upon this indictment the defendants were deprived of their rights under the Constitution of the United States.” What was it that Holmes intuited but was unable to articulate? The answer may well be that Holmes felt a very human impulse to protect victims of those prejudices—like anti-Semitism—that to him were incomprehensible.

Suggested Reading

The Witness

Raised in an assimilated German-speaking family and baptized as a Protestant at age 12, Adler had seemed destined for a stellar literary career as an heir to the Prague Circle, a group of German-language writers that included Kafka, Max Brod, and the philosopher Hugo Bergmann. His imprisonment in Theresienstadt changed the arc of his career and gave us some of the most powerful testimony about the inner life of the camps that has ever been written.

A “New History” and Old Facts

Fifty years after the conflict, Guy Laron’s The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East attempts to upend our understanding of the hostilities.

“I Am Impossible”: An Exchange Between Jacob Taubes and Arthur A. Cohen

In the summer of 1977, two old friends ran into each other in front of a Paris bookstore and found themselves arguing about Simone Weil, Judaism, and their lives.

Counting Jews

Tim Grady makes a careful but controversial case about the way Jews contributed to or supported Germany's worst excesses in World War I.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In