Loaves in the Ark

This striking tale of mistaken but nonetheless pure faith, divine fiat, and free food in 16th-century Safed comes from a book by Rabbi Moses Hagiz entitled Mishnat Chakhamim (Wandsbeck, 1733; pp. 52). It is one of a number of versions in circulation, including some fanciful variants.

Hagiz (ca. 1671-1750) spent much of his life wandering through Europe fighting the heresy of the Sabbateans. While the Hebrew wording is slightly obscure, his apparent claim to have heard the tale from contemporaries of Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534-1572) can’t be true. Luria, the great kabbalist of Egypt and Safed, did, however, have contact with conversos—those descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jews whose ancestors had converted to Christianity in the 14tth and 15th centuries. A tradition preserved in the late-16th-century hagiography Toledot ha-Ari reports that Luria acquired his first mystical book from a recently re-Judaized converso who could not himself read Hebrew. Portuguese priests who visited Safed at the time found homesick conversos there anxious to hear the news from their land of origin. Thus, the presence of a converso family recently returned to Judaism in Safed is not unlikely. In addition, Luria was widely believed to have had access to the deliberations and decisions of the “heavenly academy.”

The Christian upbringing of the conversos plays an important role in the story. The Portuguese man’s error may well relate to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, according to which the wine and wafer ingested at communion become the actual substance of the blood and body of Jesus. This man’s invented ritual (enabled, it should be noted, by the labors of his wife) is a sort of mirror image of the Eucharist: God consumes the bread as a sacrifice from man. Perhaps this is why the rabbi is so quick to label this an act of anthropomorphic heresy. The original showbread, one of the regular offerings given by the ancient Hebrews in the Tabernacle and Temple, was never meant to be “eaten” by God; the priests, in fact, were entitled to eat it after it had been displayed for a week.

The end of the story plays on the tension throughout pre-modern Jewish thought between a rationalistic approach to Judaism that emphasizes the transcendence of God, and a mystical approach that emphasizes God’s immanence. From a rationalist point of view, the rabbi is perfectly correct in his rebuke, if not in its delivery. This, however, is a mystical tale whose sentiments are altogether with the immanent God who loves and draws enjoyment and even sustenance from the simple, passionate commitment of the converso, as well as, apparently, the all-too-human enjoyment of the synagogue attendant. The rabbi’s combination of rational theology and personal coldness—a trait often associated with rationalism—constitutes, apparently, such a serious breach with true Jewish values that he must die for his error.

A story was told to me by trustworthy people and elders from that generation of special wisdom who lived in the days of Rabbi Isaac Luria of blessed memory [the Ari, z”l]. An episode occurred concerning one of the conversos [anusim] who came from Portugal to the upper Galilee, to the holy city of Safed, may God rebuild and establish it. He listened to the rabbi of one of the holy congregations there who delivered a sermon on the matter of the showbread that was offered in the Holy Temple every Sabbath. Apparently, this rabbi sighed sorrowfully during his sermon and commented, “But now, in our multitude of sins we have no worthy vessel [i.e. the Temple] that is able to draw down the divine efflux [shefa’] on the unworthy [the rest of the world] as well.

This converso, in his simplicity, went home and told his wife that under all circumstances, every Friday she must bake him two loaves of bread risen thirteen times and kneaded in purity. They should also be beautified in every manner and baked with care in the oven at home. His intention was to offer these at the sanctuary of God [le-hakrivam lifnei heikhal Hashem; that is the ark where the Torah scrolls are kept]; perchance God would show him favor, accept them, and consume this offering. His wife did it just as he had described, and each Friday he would present the two loaves at the ark. He would pray and beg before blessed God that they would be accepted with good will, that God would consume them, that they would be pleasant to Him, and that they would make Him glad. He would speak words in this way; he would talk and plead like a son pleading before his father. He would then put down the loaves and exit.

After this, the synagogue attendant would come and take the two loaves of bread without investigating whence they came or who brought them. He would eat them with great enjoyment and contentment. Later, at the time of the evening prayer, that God-fearing [Portuguese] man would run to the ark, and, finding that the loaves had vanished, would be filled with exceeding joy in his heart. He would go home and say to his wife, “Praise and thanks to the Lord, may He be blessed, for He has not rejected the proffering of a poor man—he has already received the bread and eaten it while it was hot! For God’s sake, do not diminish your efforts in making them, and be very careful, because we have no other means of honoring Him. We see that this bread is agreeable to Him, so it is our duty to bring Him contentment [nachat ruach] with them.” He kept this practice up with great regularity for some time.

It happened that one Friday, the selfsame rabbi of the holy congregation—the one whose sermon had led this man to bring the loaves—was at the synagogue, standing on the bimah reviewing the sermon he planned to deliver the next day, the Holy Sabbath. The man now came according to his good tradition carrying his loaves and approached the ark. He began to utter his thoughts and prayers as was his habit, never noticing that the rabbi was standing on the bimah, because of the deep exhilaration and joy he felt at that moment from bringing this gift before the Lord.

The rabbi remained silent, observing and listening to all that the man said and did. He became truly furious. He called to the man and castigated him, saying, “Fool! Does our God eat and drink? It must be that the attendant has been taking it. And you, meanwhile, thought it is God who has been accepting them! It is a great sin to attribute any physical qualities to God, may He be blessed, for He has neither a body nor the shape of a body.” He continued rebuking the man in this manner until the attendant arrived to take the loaves as he usually did. When the rabbi saw him, he called him over and told him, “Give thanks to this man for that which you came to get. Who exactly was it that took the two loaves that this man was bringing here to the ark every Friday?” The attendant unabashedly admitted to it.

When he heard this, the [Portuguese] man began to cry. He asked the rabbi to forgive his error in misunderstanding the sermon, and for thinking he was performing a great deed when he was in fact guilty of a transgression, as the rabbi had said.

While all this was going on, a special envoy from Rabbi Isaac Luria (of blessed memory) arrived for the rabbi. He declared in the name of the godly rabbi of blessed memory, “Go to your house. Tell your household that tomorrow, at the moment you were to deliver your sermon, you will surely die. The decree for this has already been promulgated.”

The rabbi was shocked by this terrible news and hurried to Rabbi Luria in order to learn what his sin and transgression had been. Rabbi Luria responded, “I have heard that it is because you have put a stop to God’s contentment. For, from the day the Temple was destroyed God had no contentment like that He enjoyed at the moment when that converso would bring the two loaves with the simplicity of his heart and present them before the ark, thinking that God accepted them from him. Your action in obstructing him from bringing them caused the proclamation of your death sentence with no chance of a reprieve. The rabbi who had delivered the sermon went home and commanded his household [to prepare]. On the Sabbath day, at the very hour when he was to preach, he passed away into the next world as Rabbi Isaac Luria, the man of God, had told him would happen.

Suggested Reading

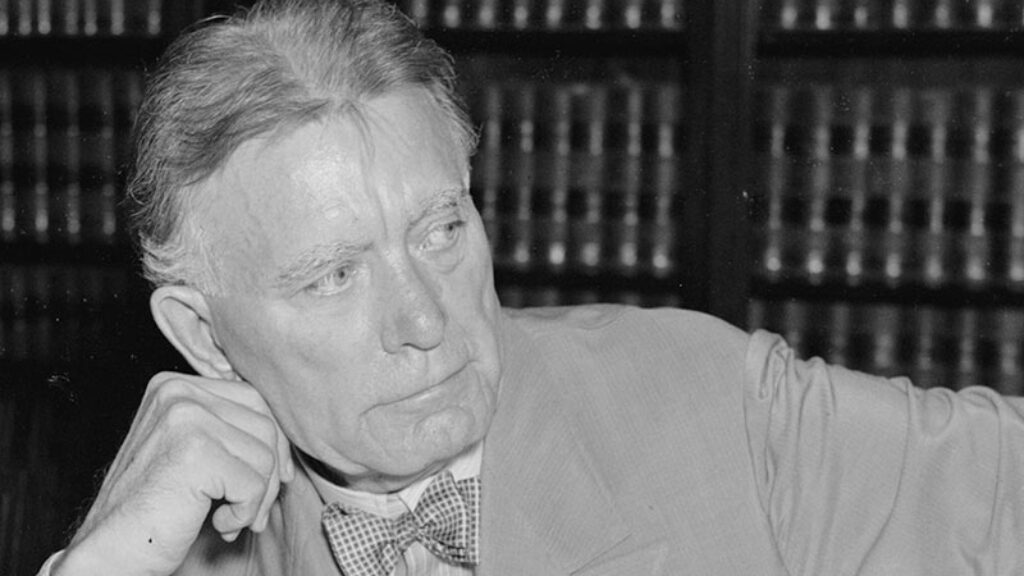

Horace Kallen, George Washington, and the Borah Affair

Was a quote from George Washington about isolationism real or fake, as Senator William Borah maintained, in a serious blow to Horace Kallen’s reputation?

Letters, Summer 2019

Garden Betrayed, Mysterium Tremendum or Coping Mechanism?, Lucifer in the Details

The Mighty Jacobson

For an American Jew to read the magnificently funny and serious Howard Jacobson is to understand just how different the situation of English Jews is from their own.

The One and the Many

A popular new book deals with differences between the world's religions, but misses the mark in several of them.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In