Everything Is PR

Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia opens with Oliona, a 22-year-old “gold-digger” with a perfect body. When she was 20, Oliona ran away from the Donbas, an east Ukrainian mining region presently the site of a war between Russian-backed separatist forces and the Ukrainian state. In Moscow, she worked as a stripper at a casino before she succeeded in meeting a “Forbes”—a billionaire in search of a mistress. Now she lives in a brand-new apartment and receives a car, $4000 a month, vacations in the Middle East, and a small dog—“the basic Moscow mistress rate.” For the moment things are good: She frequents the most expensive sushi bars and the most selective nightclubs. She giggles and wears sparkly dresses and has memorized a few stanzas of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin to impress a Forbes who likes literature. Then again, neither the apartment nor anything in it belongs to her. And her shelf life is not long; she is competing with thousands of 18-year-olds who can do gymnastics in stilettos.

Oliona is not a prostitute. To her the distinction is nontrivial: She has no pimp. She chooses her billionaire lovers. Dinara, who is of Oliona’s generation and equally sympathetic and even cheerful, works under much less glamorous conditions. She grew up in the Russian republic of Dagestan, east of Chechnya. Now she spends her evenings at a weakly lit proletarian bar near a train station. She lets Peter Pomerantsev buy her whiskey and colas and pizza—but not with pepperoni, because she is a Muslim. Wahhabi preachers from Saudi Arabia have captivated her sister, who now wears a headscarf and is contemplating becoming a Black Widow, a suicide bomber. “Two sisters. One a prostitute. The other on jihad,” Pomerantsev summarizes.

Pomerantsev, a Kiev-born British television producer in his mid-30s, spent a decade working in post-Soviet Moscow. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible is a portrait of Putin’s surreal new Russia, an alternative reality composed of intersecting alternative realities. A native Russian speaker with a slightly odd accent, the author spends a lot of time with prostitutes, gangsters, emotionally unstable supermodels, television journalists, and “political technologists.” He is probing, inquisitive, voyeuristic—as journalists must be if they are any good. Yet he is also a deeply decent person, who never forgets that he is dealing with human beings:

[Dinara] liked being a prostitute—or at least she didn’t mind. But what of Allah? He hated whoring. She could feel his rebuke. It kept her awake at night.

I told her that I’m sure Allah keeps things in perspective.

His irony veils a human empathy of which he cannot quite rid himself, even when circumstances are inauspicious.

“Did you always want to be gangster?” Pomerantsev asks Vitaly. They are filming an interview. Vitaly, characteristically, is wearing a designer tracksuit, carefully ironed. His “alma mater” is prison. He drinks cappuccino and plans to become a filmmaker, having been inspired by Titantic starring Leonardo DiCaprio. “How many have you killed?” Pomerantsev asks him. “I can only talk about one time. That was revenge for my brother,” Vitaly answers, almost apologetically. Gangsters, we learn, can be likeable, even sensitive in their way.

Oliona’s first boyfriend—the only one she ever loved—was a local gangster in her town in the Donbas. One day two rival gangsters kidnapped her and took her back to their vodka and pickled fish–scented apartment filled with barbells and decorated with a Soviet flag; they tied her to a chair and raped her repeatedly. “Happens to all the girls. No biggie,” she tells Pomerantsev.

“Do I even need to mention that Oliona grew up fatherless?” Pomerantsev writes. “As did Lena, Natasha, and all the gold diggers I met. All fatherless. A generation of orphaned, high-heeled girls, looking for a daddy as much as a sugar daddy.” The ultimate sugar daddy in this story, of course, is Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin:

Strippers writhe around poles chanting: “I want you, Prime Minister.” . . . The mood at the “Putin Party” is a mix of feudal poses and arch, postmodern irony: the sucking up to the master completely genuine, but as we’re all liberated, twenty-first-century people who enjoy Coen brothers films, we’ll do our sucking up with an ironic grin while acknowledging that if we were ever to cross him, we would quite quickly be dead.

Not only morality, but also reality itself is ambiguous here: Pomerantsev describes Russia as a “fragile reality show” choreographed by the political technologists. The role of mass media is dazzling—like the effect of the new money and the disorienting juxtapositions of the pre-modern and the post-modern: oligarchs and peasants, glittering dance clubs and moldy Soviet prison cells, warlords who use Twitter.

“Propaganda,” an old-fashioned word, relates to Soviet times. The new Russia generates “PR.” “Everything is PR” has become Moscow’s guiding principle. The state-sponsored television station Russia Today (RT) presents “a Russian point of view.” Many who work at television stations like RT are personally, “subjectively” liberal. Yet they are easily induced to ask the right questions, such as “Why is the opposition to you so small, Mr. President?” In any case—they argue—why not allow Russia to have a point of view? It all becomes a matter of perspective, articulated with language borrowed from corporate capitalism: Putin is “the President of ‘stability.’” (“‘Stability,’” Pomerantsev writes, “the word is repeated again and again in a myriad of seemingly irrelevant contexts until it echoes and tolls like a great bell and seems to mean everything good.”) Stalin was an “effective manager.” Putin is “the most ‘effective manager’ of all.” Foreigners and other well-meaning people who work for RT justify their participation with the enlightened thought that “There is no such thing as objective reporting.” They are also well paid. “Everyone is for sale in this world,” Pomerantsev writes, “even the most ‘liberal’ journalists have their price.”

This is a book full of sex, violence, and disco music. My undergraduate students at Yale loved it; some read it in one sitting. The narrative features pink heels, private helicopters, and fantastical Midsummer Night’s Dream parties with trapeze artists and synchronized swimmers dressed as mermaids. It also features a seven-year-old who weighs over a hundred kilos (220 pounds), a supermodel who jumped from her apartment to her death nine floors below, and hot dog stands that catered to the onlookers who appeared outside a Moscow theater while Chechen terrorists held everyone inside hostage.

One story Pomerantsev tells is of Yana, another alluring young woman with an enviable wardrobe and a private fitness trainer. Yana, who runs a successful business trading in industrial cleaning products, is inexplicably arrested. She learns that the key ingredient in the cleaning products—for which she has a license—has suddenly, with no warning or explanation, become illegal. She is sent to prison; her lover Alexey leaves her. The interrogations begin to drive her to insanity: “Black is white and white is black. There is no reality. Whatever they say is reality.” All Yana can do is scream.

In her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics,” Hannah Arendt returned to the issue of the totalitarian regime’s attitude toward truth. At issue here—Arendt clarifies—are not the principles of geometry or Kant’s categorical imperative, but “factual truth”—empirical and thus necessarily contingent facts, such as the truth that in 1914 Germany invaded Belgium. It is this second kind of truth, Arendt tells us, that is assaulted by modern totalitarian regimes—either through outright denial or “the blurring of the dividing line between factual truth and opinion.” Those who lie are activists who want to change the world and who might well succeed. “It is true,” Arendt writes, “considerably more than the whims of historians would be needed to eliminate from the record the fact that on the night of August 4, 1914, German troops crossed the frontier of Belgium; it would require no less than a power monopoly over the entire civilized world.” She adds: “But such a power monopoly is far from being inconceivable.”

Rereading Arendt’s essay after watching Putin’s March 2014 Crimea speech is uncanny. The late February 2014 victory of the popular revolution on Kiev’s Maidan was the beginning of an undeclared Russian invasion of Ukraine. So-called “little green men” wearing black masks and unmarked camouflage, not admitting to being Russian forces, appeared on the Crimean peninsula. Within days, a fraudulent referendum and the annexation of Crimea became the occasion for Putin’s hypnotic speech on March 18, 2014.

A referendum was held in Crimea on March 16 in full compliance with democratic procedures and international norms. More than 82 percent of the electorate took part in the vote. Over 96 percent of them spoke out in favor of reuniting with Russia . . . In people’s hearts and minds, Crimea has always been an inseparable part of Russia. This firm conviction is based on truth and justice and was passed from generation to generation, over time, under any circumstances.

The RT camera continually turned from Putin to faces in the audience: approving, beaming, eyes welling with tears of joy.

In “Truth and Politics” Arendt describes old-fashioned lies as a tear in the fabric of reality; the careful observer can perceive the place where the fabric has been torn. In contrast, totalitarianism brought something new: The “modern political lie” involves the creation of a seamless new reality. There is no tear to perceive.

One of the best films made about Stalinism is the 1982 film Interrogation, set nearly in its entirety inside a Stalinist prison cell. Krystyna Janda plays Tonia, a promiscuous young nightclub singer in postwar Poland, full of both joie de vivre and despair over her husband’s suspected infidelity. When she is arrested on fictitious charges of aiding enemies of People’s Poland, her interrogators are willing to use all means at their disposal to extract a confession. A certain Olcha, whom the interrogators allege is her lover, has been accused of espionage. Tonia is stunned, disoriented, indignant. The interrogations continue. The interrogators’ narrative develops: Tonia resists, denies everything, changes details in her story, and gradually resigns herself to greater portions of the interrogators’ narrative, although never to that narrative in its entirety.

What the film conveys so vividly is not only life under Stalinism, but also a philosophical stance: There is epistemological confusion (confusion about knowledge), but never ontological confusion (confusion about being). Stalinist prison is a site of fictions and manipulations. We never learn the true story: who—if anyone—had in fact opposed the regime, which men had been Tonia’s lovers, who Olcha was and what he had actually done. What we are certain of, though, is that there is a true story. We never learn what it is, but we are never given to doubt that it has an objective existence, that there is a distinction between truth and lies, fact and fiction, that there is such a thing as reality.

Interrogation represents the modernist position: God may be dead, but that does not mean that truth is, even under a totalitarian regime. Not so in the surreal new Russia Pomerantsev describes.“[W]hen the President will go on to annex Crimea and launch his new war with the West,” he writes, “RT will be in the vanguard, fabricating startling fictions about fascists taking over Ukraine.” This new war Putin launched with the West is being played out in the Donbas, where Oliona grew up. To this day it remains unclear what is happening there. Who is a Kremlin agent? Who is a mercenary? Who has been encouraged with some money to act on his already-existing inclinations? Who is behaving authentically? Who began as a paid provocateur but has lost a sense of the script? Who no longer knows who he is himself?

“I sense the politics of provocation have led to a crisis of subjectivity in the east,” I said to a Ukrainian friend when we met in Kiev in May 2014. “Yes,” he said ironically, “we are very post-modern.”

Kateryna Iakovlenko is one of the young organizers of Izolyatsia, a contemporary art center in the Donbassian city of Donetsk, whose space was seized by militants of the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and turned into a prison. Some of the unidentified “little green men” who came to Donetsk were Chechens who did not speak very much Russian and could not understand why Ukrainian currency came out of the bank machines instead of Russian rubles. On one occasion the Chechens fighting on the separatist side organized a meeting on Lenin Square. An elderly local woman attended and gave one of the Chechens an Orthodox christening to aid his victory in battle against the Ukrainian Nazis. The German surrealist painter Max Ernst once described surrealist collage as “the coupling of two realities which apparently cannot be coupled on a plane which apparently is not appropriate to them.” For Iakovlenko that scene was a macabre surrealist collage: an Orthodox Christian woman on a communist square christening a Muslim mercenary soldier to go kill phantom Nazis.

This is what Pomerantsev tries to make us understand: In Putin’s Russia today there is not only a problem of knowledge about truth, but also a problem of the very existence of truth. “The great drama of Russia,” Pomerantsev writes, “is not the ‘transition’ between communism and capitalism . . . but that during the final decades of the USSR no one believed in communism and yet carried on living as if they did, and now they can only create a society of simulations.”

In his 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” Václav Havel describes an ordinary greengrocer, who every day puts the sign saying “Workers of the world unite!” in his vegetable shop window. Of course the greengrocer does not believe the sign’s message, nor do the passers-by, nor even does the regime. Nonetheless, everyone goes on pretending; they live as if they believed in communism. The paradigm of living “as if”—pretending to admire the emperor’s new clothes—was long the dominant mode of understanding late communism in both Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

Several years ago, the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak contested this paradigm in his 2006 book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. For Yurchak “as if” is too binary; it falsely implies a stable if unarticulated clarity. He insists on the fluid space between dissidence and conformity, authenticity and inauthenticity, power and resistance. This is postmodernism: When we give up on replacing God and accept that there is nothing to guarantee the stability of self, world, truth. Pomerantsev’s anecdotal insights lead us precisely here: It is not so easy to determine what people “really” believe, where the boundary is between gullibility and enlightened cynicism. Everything is in flux.

“It’s like they can define reality,” Yana, the businesswoman, says of her imprisonment and interrogation in the new Russia, “like the floor disappears from under you.” Arendt called this groundlessness (Bodenlosigkeit): “Consistent lying, metaphorically speaking, pulls the ground from under our feet and provides no other ground on which to stand.” Pomerantsev portrays Putin’s Russia as a kind of collective giving up on truth—and an attempt to take it lightly.

“And then you realize,” Pomerantsev writes, after he accompanies Oliona to a nightclub for the super-wealthy, “how equal the Forbes and the girls really are.”

They all clambered out of one Soviet world. The oil geyser has shot them to different financial universes, but they still understand each other perfectly. And their sweet, simple glances seem to say how amusing this whole masquerade is, that yesterday we were all living in communal flats and singing Soviet anthems and thinking Levis and powdered milk were the height of luxury, and now we’re surrounded by luxury cars and jets and sticky Prosecco. And though many westerners tell me they think Russians are obsessed with money, I think they’re wrong: the cash has come so fast, like glitter shaken in a snow globe, that it feels totally unreal, not something to hoard and save but to twirl and dance in like feathers in a pillow fight and cut like papier-mâché into different, quickly changing masks.

Pomerantsev’s tone is light throughout, deceptively so, for between the lines he is deadly serious. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible is arguably the most philosophically perceptive attempt to illuminate Putin’s Russia that we have. Recently, at a conference, I spoke with a Russian colleague. Being in Moscow, she said, felt like being in a Road Runner cartoon where Wile E. Coyote keeps running even after the bridge has long since disappeared from underneath him.

Suggested Reading

EUGENE NADELMAN: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse

"Our tale's debut / Takes place in 1982 / When I, for one, if not exactly / A double of our leading guy / Was like him, bookish, awkward, shy." - Coming of age in iambic tetrameter.

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

What a Friend We Have in Jesus

A new crop of books about Jesus, by Jews and for Jews.

Getting Along with the Gentiles

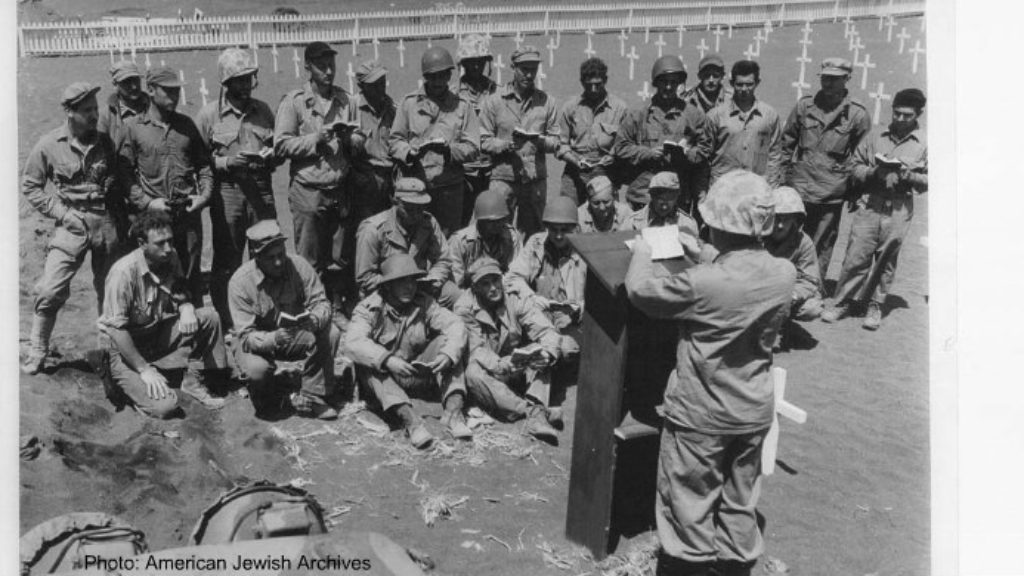

From the Brandeis Book Stall to the sands of Iwo Jima (and halakhic flexibility).

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In