Desk Pounding and Jewish Leadership

Long-time leaders of Jewish organizations are not easily retired, but by 1943, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise realized he could no longer steer the American Zionist movement unassisted. Approaching 70 and in declining health, Wise already had his hands full with his duties as head of the American Jewish Congress, the World Jewish Congress, and his rabbinical seminary, the Jewish Institute of Religion. Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, suggested bringing in Abba Hillel Silver, a prominent 49-year-old Cleveland rabbi and dynamic Zionist orator. Wise reluctantly agreed that “the work should come into the hands of a younger and stronger man—and he is the man.” Silver was named co-chair, alongside Wise, of the American Zionist Emergency Council, the umbrella for the major U.S. Zionist groups. The American Jewish community would never be the same again.

The Wise-Silver alliance did not last long. Barely a year later, Wise wrote to a colleague: “Pray for me. I need the intervention of divine protection, unless I want to perish at the hand of the co-Chairman of the Emergency Council.” Clashing personalities and dueling egos were part of the problem, but political differences were the real issue. Wise, a staunch supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt, advocated political caution and Jewish loyalty to the Democratic Party. Silver, an advocate of forthright political activism, sought to increase Jewish leverage in Washington by convincing Republican leaders to woo Jewish voters. When the GOP added a pro-Zionist plank to its 1944 platform, the Democrats were forced to match it. All this Jewish infighting, competition for Jewish electoral support, and tension with the White House may sound familiar to observers of the contemporary political scene. The fact that the Zionist lobbyist Benzion Netanyahu was deeply involved in the 1940s contacts with Republicans only makes the parallels seem all the more uncanny.

The trouble between Wise and Silver came to a head at the end of 1944, when Silver, over the Roosevelt administration’s objections, pressed for a congressional resolution endorsing Zionist aims—while Wise was quietly assuring the White House that he would do nothing for the resolution against the president’s wishes. This conflict provided Wise the pretext he needed to engineer Silver’s ouster. Within six months, however, a wave of grass-roots pressure returned Silver to power. Ofer Shiff, in his new study The Downfall of Abba Hillel Silver and the Foundation of Israel, explains Silver’s resurgence this way: “Silver’s public strength lay in his success at using Zionism as a means of transforming American-Jewish concerns into a determined demand on behalf of American-Jewish citizens for thoroughgoing rectification of Jewish marginality.” This is a somewhat overwrought way of saying the horrors of the Holocaust and England’s turn against Zionism convinced many American Jews that Silver’s activist approach made more sense than Wise’s strategy of caution.

In the months following the end of World War II and the ascension of Harry Truman to the presidency, Silver mobilized a nationwide network of Zionist activists—Christians as well as Jews—to undertake a massive campaign of rallies, lobbying, petitions, and other protests to persuade the Truman administration to support Jewish statehood. According to Shiff, the reason Silver’s campaign attracted widespread support was that it appealed to Jews who wanted “to actively express their solidarity with the [Holocaust] victims and survivors but who wished to do so without reinforcing their sense of collective powerlessness.” At the same time, Christians liked it because it was “rooted not in a quest for exclusivity, but rather in a desire to solve the continuous problem of Jewish marginality.” One suspects, however, that the average person signing a Zionist petition or taking part in a rally likely was responding to newsreel footage of the liberated death camps and not thinking very much about notions of collective powerlessness or marginality.

Silver encouraged the perception that Jewish voters would turn against the Democratic Party if the administration abandoned the Zionist cause. Shiff characterizes Silver’s suggestions as “crude political force,” although Truman’s advisers, assessing the mood in the Jewish community, reached similar conclusions. They repeatedly warned the president that Jewish anger over his Palestine policy could result in Democratic losses in the New York City mayoral race of 1945, in congressional elections in 1946, and ultimately in key electoral states in the 1948 presidential contest. Not surprisingly, Truman resented this intrusion of domestic politics into Middle Eastern policy. He fumed at having Palestine distract his attention from the struggle with the Soviet Union over post-war Europe. He feared the United States was being dragged into an unwanted overseas conflict in the Middle East—a conflict he believed was, as Shiff puts it, “potentially capable of unleashing a third world war.”

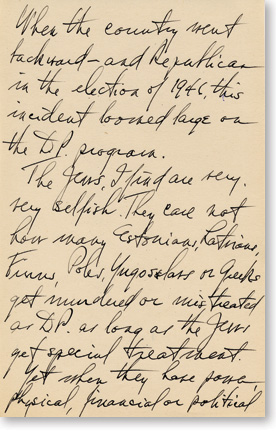

This was, however, more than the usual irritation a president feels over nettlesome policy battles. A staffer at the Truman Library not long ago stumbled upon a previously unknown diary the president kept, in the back of an old ledger, which included this jarring comment, dated July 21, 1947:

The Jews have no sense of proportion nor do they have any judgement on world affairs. . . . The Jews, I find are very, very selfish. They care not how many Estonians, Latvians, Finns, Poles, Yugoslavs or Greeks get murdered or mistreated as D[isplaced] P[ersons] as long as the Jews get special treatment. Yet when they have power, physical, financial or political neither Hitler nor Stalin has anything on them for cruelty or mistreatment to the under dog.

That harsh sentiment dovetailed with previously documented statements made by Truman about Jews, such as this remark in a July 30, 1946 cabinet discussion about Jewish dissatisfaction over his Palestine policy: “Jesus Christ couldn’t please them when he was here on earth, so could anyone expect that I would have any luck?”

Shiff alludes to Truman’s “caustic” remarks about Jews, but sidesteps the recent controversy concerning those remarks. This is surprising, considering the implications of the episode. For American Jews who revere Truman for his recognition of the newborn State of Israel, the revelation of the diary entry came as quite a shock. There were even those who tried to explain it away by blaming Silver. Bruce S. Warshal, a Florida rabbi and one-time newspaper publisher, writing in the journal of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, argued that Truman’s anti-Semitism was an understandable response to the fact that “while Truman was working . . . to help Jews, he was the object of ever-increasing Jewish political pressure.” The president had a right to be “livid,” according to Warshal, because “Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, one of the leading American Zionists of the time, actually stormed into Truman’s office and pounded his fists on his desk.”

The fist-pounding allegation shows up with remarkable frequency in books and articles about the period. Often it is presented as evidence that the obnoxious, belligerent Silver—as the face of obnoxious, belligerent American Jews in general—endangered the entire Zionist enterprise through his outrageous attempt to physically intimidate the president of the United States. Silver’s “militant” approach “occasionally backfired,” a typical account asserts, claiming that Silver’s fist-pounding led him to be banned from the White House, and “[h]ad not cooler heads prevailed, Truman might not have come to the fateful decision of recognizing Israel.” The story is an indictment not only of Silver the man, but of the entire strategy of forthright Jewish political behavior. Over the years, the tale has made its way from narrow histories of American Zionism to major biographies of Truman, such as Robert Ferrell’s Harry S. Truman: A Life and David McCullough’s best-selling Truman. Rabbi Warshal, however, seems to be the first to use the fist-pounding story to claim that Silver provoked Truman into an anti-Semitic outburst.

It is not clear how Silver could have “stormed” (Warshal’s term) Truman’s office, in view of the Secret Service agents guarding the premises. Moreover, on the only two occasions Silver visited the White House during the Truman years, he was accompanied by Stephen Wise in one instance, and by Wise, as well as Zionist officials Nahum Goldmann and Louis Lipsky, in the second. Yet there is no fist-pounding mentioned in either Truman’s published memoir, or in the autobiographies or private correspondence of Silver, Wise, Goldmann, or Lipsky. A little sleuthing reveals that if one traces the allegation back far enough, it ultimately leads to a remark once made about Silver by Elinor Borenstine, the daughter of Truman’s Jewish friend and business partner, Eddie Jacobson. Mrs. Borenstine, however, was relying on a 1968 essay by her father, in which he reported only Truman’s complaint about “how disrespectful and how mean certain Jewish leaders had been to him.” Jacobson wrote nothing about fist-pounding, nor did he even mention Silver by name. His daughter’s embellishment triggered a small avalanche of baseless accusations that reverberate to this day.

There is an interesting footnote to this episode. On March 10, 1948, syndicated columnist Drew Pearson reported what he described as a recent conversation about Palestine between Truman and New York Post publisher Ted Thackrey. Pearson wrote: “Pounding his desk, [Truman] used words that can’t be repeated about ‘the (blank) New York Jews.’ ‘Those (blank) New York Jews are disloyal to their country. Disloyal!’” Thackrey responded, “When you speak of New York Jews are you referring to such people as Bernard Baruch? Or are you referring to such New York Jews as my wife [Dorothy Schiff]?” According to Pearson, “Truman glared, assured his visitor he did not mean to include Baruch or the publisher’s wife, then abruptly changed the subject.” Truman denied the story; Pearson stood his ground. Is it possible that Truman, in his complaints to Eddie Jacobson or others about “disrespectful” Jewish behavior, was actually projecting something of his own intemperate ways?

The major focus of Shiff’s book, as its title indicates, is the post-statehood period. American Zionist organizations did not go out of business once Israel was established. Instead, they turned their attention to fundraising for the new state, while at the same time devoting considerable time to fretting over—and quarreling with Israeli leaders about—the nature and purpose of Zionism in the diaspora. As Shiff shows, Silver articulated a Zionist vision in which a comfortable and content American Jewish community would continue to thrive, alongside the young State of Israel. Not surprisingly, Israeli leaders would have preferred a more Israel-centric arrangement, in which American Jewry devoted itself almost entirely to Israel-related philanthropy and actively encouraged its youth to make aliyah. It was, however, an argument with precious little impact in the real world. Regardless of what Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion or other Israeli leaders preferred, or how either side defined Zionism or Israel-diaspora relations, very few American Jews were going to make aliyah or even take a serious interest in any of the various flavors of Zionist ideology. Membership in all U.S. Zionist organizations declined sharply after 1948.

One can understand why Shiff was tempted to draw some contemporary lessons from these post-war intra-Zionist squabbles. After wading through 270 pages of Zionist inside baseball, a weary reader might legitimately ask: So what?

But Shiff’s attempt to answer that question takes matters a little too far. In Shiff’s telling, the post-1948 bitterness between Silver and Ben-Gurion reflected “a much broader struggle” that is “still relevant today.” On one side of this alleged struggle stood Ben-Gurion, with a “statist-Israeli agenda” that finds “its cruder echo” today among “Jewish national and religious extremists” who favor “exclusionism” and want to “separate Jews from their non-Jewish surroundings.” On the other side of the 1950s debate stood Silver, who, according to Shiff, viewed the State of Israel “as a scaffold for the implementation of a universalistic Jewish vision.”

Certainly Shiff is correct that Silver regarded the creation of the State of Israel as the first step toward an era of universal peace and brotherhood rather than the ultimate goal, but that is what one would expect of a Zionist-minded Reform rabbi. As a matter of fact, it is not much different than the long-range vision of the Labor Zionists, with their dream of a socialist Jewish state as part of a socialist world, or the religious Zionists, with their dream of a Torah state as part of a messianic era. But Silver’s speeches in this regard sound more like boilerplate sermons than planks in an action agenda. When Shiff attaches words such as “universalistic” and “postnationalist utopia” to Silver’s post-war rhetoric, he is invoking terminology that has stronger political implications now than it did then. A 1956 sermon in which Silver referred vaguely to the notion that “Judaism is mankind’s religion of hope and renewal” is understood by Shiff to mean that Silver actually was promoting “a new model in which the existential anxieties occasioned by the Holocaust had to be translated into a global universalistic message.” Such over-reading is at least partly motivated by Shiff’s attempt to contrast Silver the universalist with Ben-Gurion the “statist.”

There was, to be sure, plenty of bad blood between Ben-Gurion and Silver, but was it the result of a profound philosophical disagreement? There were more than enough personal and political differences between them to ensure years of acrimony. To begin with, Silver was known to have been sympathetic to Ben-Gurion’s arch-enemy, the Irgun Zvai Leumi, the Jewish underground army led by Menachem Begin during the British Mandate years. That alone would have sufficed to land him on Ben-Gurion’s enemies list.

Moreover, while Ben-Gurion was a devout socialist, Silver supported the General Zionists, who advocated free enterprise and compulsory arbitration to resolve labor disputes. It is no coincidence that the period of greatest tension between the two men occurred in the early 1950s, when the General Zionists increased their Knesset representation from seven seats to 20, making them the second largest party in Israel’s parliament. The swirl of rumors in the Israeli press about Silver supposedly planning to make aliyah and become leader of the General Zionists surely stoked Ben-Gurion’s perception of him as a dangerous rival. Ben-Gurion’s calculated snubs of Silver during the latter’s visit to Israel in 1951, and again during Ben-Gurion’s visit to the United States shortly afterward, probably had more to do with the cut-throat nature of Israeli politics than a theoretical disagreement about the role of Zionism in the diaspora.

One does not need to put the speeches of Abba Hillel Silver under a magnifying glass to understand their meaning, and his post-1948 sermons were not intended to combat “Jewish national and religious extremists,” as Shiff suggests. Nor, conversely, was Silver a fist-pounding fanatic who jeopardized the Zionist cause. He was passionate and did not always mince words, but he was not an irrational bully; he knew how to comport himself in the presence of the president of the United States, as Marc Lee Raphael showed in his 1989 biography, which remains the finest study of the man and his legacy. American Zionists, under Silver’s leadership, carried forward a program of protests and lobbying that was entirely within the bounds of democratic discourse.

Suggested Reading

Dress British, Think Yiddish

Stanley Kubrick was a New York Jew, fascinated with photography, jazz, and chess. He took evening classes at City College and studied at Columbia with Lionel Trilling.

The Nazi Rosetta Stone

The interagency task force meeting at an elegant suburban estate was like any other such meeting, except for its agenda: the “final solution.”

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

Why the Germans?

Was Nazi hatred of the Jews driven by envy of their economic and social success or rather by a fear of a perceived threat to German culture and identity?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In