Why the Germans?

The two questions that make up the title of the German scholar Götz Aly’s latest book are the ones that many historians of the Holocaust have been attempting to answer for decades. And as the book’s subtitle suggests, the answer that Aly supplies is not radically new. The novel twist in his argument consists of the way he links envy and race hatred as causal factors: Aly argues that the German people’s “gnawing envy” of the Jews ended up combining “with a collectivist longing for a life among equals” and “paved the way for [the] racial theory” that the Nazis employed in their genocidal assault on the Jews in their own country and beyond.

What made the German Jews so enviable, Aly explains, was the way that they took advantage of the new economic opportunities that arose in the course of the 19th century, as the old feudal order gave way to the modern world. More literate and academically agile than their Christian peers, German Jews were “eight times more likely to earn a better class of secondary-school degree” and used their “educational head start” to pursue “well-paying forms of intellectual labor.” By 1914, Aly reports, they earned “five times the income of the average Christian.” As a consequence, “the Christian majority, only too conscious that they needed to move up the social ladder, became obsessed with how quickly Jews were bettering themselves.”

This economic disparity was hard enough for Germans to stomach, but it was all the more painful given their collective insecurity as the inhabitants of a historically divided polity. Thanks to the traumas of the Thirty Years’ War and the Napoleonic invasions, the German people lacked a sense of “self-confidence” and thus sought to overcompensate by embracing an exaggerated sense of national identity. Tragically, according to Aly, this identity was based upon “weakness, timidity, self-doubt, resistance to progress, pent-up aggression, and xenophobia.” The Germans’ resulting “hypersensitivity toward minorities” explains why anti-Semitic outbursts erupted in the early 1800s, not only in the writings of intellectuals, such as Ernst Moritz Arndt, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, and Jakob Friedrich Fries, but in the form of pogroms, such as the Hep Hep Riots of 1819.

Anti-Semitism further intensified following the unification of the German Empire in 1871. Especially after the economic crash of 1873, the “losers” in the industrialization process—mostly members of the German lower middle class—found solace in the anti-Semitic agenda of Adolf Stöcker’s Christian Social Party, which called for new restrictions on Jewish economic activity. Aly quotes the liberal politician Albert Traeger as accusing Stöcker of exploiting “the jealousy of the incompetent . . . as a weapon against those with greater abilities.” Equally telling was economist Werner Sombart’s 1912 claim that because “Jews are quite a lot more clever and industrious than we [Germans] are,” it was necessary to prevent Jews from holding academic chairs, otherwise “all university lectureships and professorships would be held by Jews or Jewish converts to Christianity.’”

In a provocative twist, however, Aly goes on to argue that the envy felt by many Germans toward Jews was ironically bolstered by progressive ideals—especially those of democracy, freedom, and equality. The pursuit of democratization advanced anti-Semitism to the degree that the same masses clamoring to gain political rights from the elites sought to deny them to their Jewish competitors. Equally bound up with anti-Semitism was the craving for freedom and equality, which the German masses sought in a homogenously defined “national community,” which promised collective security in a changing world.

This clamoring for equality climaxed after World War I in the crisis-ridden years of the Weimar Republic when, against the backdrop of military defeat, socialist revolution, and national humiliation, the Nazi party promised the German masses true social equality by creating a nationally homogenous state purged of its one powerful impediment—the Jew, whose manipulation of capitalism and communism threatened to keep Germans divided and weak.

The key tool employed by the Nazis in their quest for equality was racial theory. According to Aly, the German people’s envy toward Jews fed into an exaggerated sense of racial superiority, which many observers at the time regarded as a “compensatory mechanism” for deep-seated feelings of “social inferiority.” He further adduces the class backgrounds of both the Nazi leaders and followers as evidence that the goal of “social mobility” spurred the anti-Semitic effort to dispossess the Jews. The fact that countless Germans ended up profiting from the Nazis’ anti-Semitic policies by taking the Jews’ jobs, businesses, and possessions explains why, in Aly’s estimation, “the overwhelming majority of Germans remained silent about the state’s persecution of Jews” and ultimately became active or passive participants in the Holocaust.

Aly’s argument is in keeping with his other works on the Nazi era, such as his recent book Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State, which implicates not only the political right, but also the left, in the rise and success of the Nazi dictatorship. He especially indicts what he sees as his collectivist-oriented home country’s insufficient respect for Anglo-American ideas of individual liberty. Aly’s argument also reflects a contemporary agenda. In declaring in his conclusion that “the mortal sin of envy . . . is what made the systematic mass murder of European Jews possible,” he maintains that the inability to banish such feelings from human life means that “another event structurally similar to the Holocaust could still occur.”

Aly’s account is in many ways compelling, but it is not as much of an explanation as he thinks it is. Envy accounts for a good deal of modern anti-Semitism, especially its economic variety, but it cannot provide an answer to the first question in his book’s title: “Why the Germans?” This question calls out for a comparative analysis of German anti-Semitism with that of other European countries that Aly does not provide. Moreover, his focus on envy is difficult to square with Germany’s embrace of racial anti-Semitism. Racial arguments about Jews were ultimately about Jewish inferiority and the menace that it posed to Germans. The poor, religiously traditional Jews of Eastern Europe who were murdered en masse in the Holocaust were not viewed as competitors to be envied; they were viewed as an existential threat.

Aly’s underplaying of the phantasmagorical dimension of German anti-Semitism makes it seem overly rational and creates a skewed perspective of the historical reality of German-Jewish success and German-Christian backwardness. Yes, German Jews were disproportionately successful relative to their percentage of the overall German population (of which they were less than 1 percent), but they were small enough in absolute numbers to allow ample room for Christian Germans to thrive. Jews represented 10 percent of Prussia’s university students in 1886, which, while impressive, means that 90 percent were Christian. Similarly, while 20 percent of Prussia’s millionaires were Jews, 80 percent were Christian. These and similar statistics make clear that German fears of imminent Jewish domination were chimerical.

Moreover, as Aly himself notes, the gap between German Jews’ and Christians’ success rates was narrowing at the very time that Nazi-era hatred of the Jews was intensifying. Aly attempts to explain this paradox by postulating a law that “as soon as an economically and socially backward majority . . . narrows the gap with a more quickly advanced minority, the danger of hate and violence increases.” But this fails to explain why Jew-hatred arose at an earlier time, when the equality gap between Jews and Christians was much larger.

Aly’s law also undermines the historical lessons that he wants readers to take away from his narrative. If we follow his logic, it would seem that for hatred to be combated, envy must be eradicated. But if envy is rooted in economic inequality, then the seemingly reasonable solution—imposing economic equality—would exacerbate the same collectivist tendencies that Aly says are implicated in nurturing hatred in the first place. There were forces no less powerful than envy underpinning anti-Semitism.

Alon Confino’s stimulating book advances a far less materialistic explanation of Nazi anti-Semitism. In his introduction, Confino criticizes recent theories of the Holocaust’s origins—especially those that attribute it to modern imperialism, racism, and warfare—for neglecting to incorporate the subjective role of emotions, sensibilities, and the imagination. He stresses the necessity of addressing these matters because the Nazi decision to kill the Jews was ultimately “built on a fantasy, in the sense that anti-Jewish beliefs had no basis in reality.” The Nazis, Confino writes, “waged a war against an imaginary enemy that had no belligerent intentions toward Germany and possessed no army, state, or government.” Why, then, did they launch their murderous campaign to create a world without Jews? They did so, Confino argues, in the attempt to devise a redemptive solution to “the problem of the origins of historical evil.”

Like Aly, Confino argues that the Nazis viewed the Jews “as the creators of an evil modernity that soiled present-day Germany.” They blamed the Jews for nearly every negative economic, social, political, and cultural phenomenon that had roiled German life, including:

bolshevism, communism, Marxism, socialism, liberalism, capitalism, conservatism, pacifism, cosmopolitanism, materialism, atheism, and democracy . . . as well as for sexual freedom, psychoanalysis, feminism, homosexuality, . . . jazz music, . . . Bauhaus architecture, and . . . abstract painting.

The only way to defend Germany from these modern forces, they believed, was by forging a supersessionist Nazi “modernity” that would be created via destruction—via the wholesale removal of the Jews (and Jewish influences) from German life.

Confino begins his narrative with a discussion of a notorious event that serves as his book’s leitmotif—the fact that on Kristallnacht in 1938, the Nazis demolished not only Jewish businesses and synagogues, but destroyed the Hebrew Bible. In a series of chilling passages, Confino describes how:

thousands [of Torahs were destroyed] . . . in hundreds of communities across the Reich, and not only in such metropolises as Berlin, Stettin, Vienna, Dresden, Stuttgart, and Cologne . . . but in small communities [as well]…

In Fritzlar, a small town in Hessen . . . , Torah scrolls were rolled along the Nikolausstrasse as Hitler Youth rode their bicycles over them . . . [In] Herford, . . . they shredded it to pieces to a general bellowing and laughing. In the village of Kippenheim, . . . youth threw the Torah scrolls into the local brook . . . In Aachen, Nazis tore the Torah in front of the synagogue and put scraps in their pockets, claiming it would bring them good luck . . . And in Wittlich . . . “a shouting SA man climbed to the roof, waving the rolls of the Torah: ‘Wipe your asses with it, Jews,’ he screamed while he hurled them like bands of confetti on Carnival.”

Confino contends that this very widely practiced act of cultural vandalism undermines explanations of the Holocaust as rooted in racial thinking, for the violence targeted the Jews’ sacred religious text. This rampage can be understood, however, if—as Confino argues—the Nazis established their anti-Semitic world view upon a foundation of historic “Christian anti-Judaism.” Echoing the findings of earlier scholars such as Jacob Katz and Uriel Tal, Confino shows that Nazi and Christian hatreds were fully compatible. But he stresses that the Nazis went further in their anti-Semitic campaign, striving not merely to expunge the Jews from German life, but to eradicate the Jewish roots of Christian European civilization altogether. Burning the Hebrew Bible was thus a momentous turning point in a radical campaign.

Confino’s analysis of this campaign proceeds chronologically, with his book’s early chapters describing the Nazi regime’s methodical organization of anti-Semitic rituals that subjected Jews to popular mockery, discrimination, and symbolic violence. Significantly, much of the effort to purge the malign “Jewish spirit” from German life was the product of grassroots efforts on the part of ordinary Germans, whether it was university students and professors organizing the burning of books written by Jewish and other “un-German” authors or ordinary villagers and townsfolk holding festive parades in which Jews were derided and humiliated in full public view. Confino’s inclusion of photographs (uncaptioned) of these mass spectacles provides a chilling glimpse of the popularity of the Nazis’ anti-Semitic crusade.

These ritualized events and the ensuing Nuremberg racial laws make clear that, contrary to Aly, Nazi anti-Semitism was motivated less by envy than by fear. The Nazis were obsessed with the threat that Jewish ideas posed to German culture and identity, whose purity they had to protect. To a degree, Confino agrees with Aly when he writes that the Nazis’ quest to establish a racially purified vision of Germany’s historical roots reflected its “overall insecurity about these roots,” especially compared to the Jews’ own ancient origins. Yet he is clear that it was ultimately fear—the fear of “contamination,” the fear of upheaval in “a fast-changing world”—that led the Nazis to create their own origins myth by attempting to realize the fantasy of a world without Jews.

Only by grasping the depth of the Nazis’ fears about the Jews as the ultimate symbol of evil can the regime’s accompanying efforts to rewrite Jewish and German history be understood. At the same time that the Nazis were legislatively—and after Kristallnacht, physically—persecuting Jews, they were relentlessly purging German life of any Jewish presence. The physical symbols of Jewish life—synagogues—were erased from the German landscape; Jewish history was rewritten from a Nazi perspective in the form of new Nazi institutes of “Jewish studies”; and the Protestant faith was dejudaized via the “German Christian” movement—all for the sake of creating “a German national and Christian community that was independent of Jewish roots.”

Given this agenda, the regime’s turn to mass murder was the next step. Following Hitler’s infamous January 1939 “prophecy” of the Jews’ looming annihilation in the event of a world war, the ensuing eruption of military conflict sealed the Jews’ fate. War provided new opportunities and methods to implement a radical vision that had already been established in 1933. In the years 1939–1941, the Nazis experimented with various methods—ghettoization, mass deportations, Einsatzgruppen shootings, and ultimately industrial mass murder in the extermination camps—but the ultimate goal remained unchanged: “Jews did not deserve to live among humans.”

It was not just the Third Reich’s leaders, but ordinary Germans and Jews, who sensed the radical rupture represented by this campaign. Germans, Confino explains, recognized the transgressive nature of the Nazis’ effort to destroy part of their own (Christian) cultural foundation in order to establish a new racially based empire. Soldiers, for example, wrote to their families (both in approving and horrified terms) of the moral Rubicon that had been crossed in the process of pursuing the Final Solution. Meanwhile, Jewish diarists trapped in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe were equally aware of the apocalyptic rupture that was taking place, confessing that the unprecedented magnitude of events defied description and logical explication.

Without understanding the Holocaust as an expression of the Nazis’ desire to reorder the very nature of civilization, its singularity cannot be appreciated. Confino rejects the idea of the Holocaust’s uniqueness, but he does distinguish the Nazis’ murder of the Jews from their assault against other groups during World War II. He admits that the Nazis killed “inferior” German and Slavic civilians for racial reasons, but stresses that they did so without any of the comprehensiveness that they employed in trying to solve the “Jewish question.” This is because the Nazis did not see racial purity as an end in itself, but merely a means for creating a new world purged of Jewish influence.

As an explanation of the Holocaust, Confino’s argument is more convincing than Aly’s. In addition to discussing the events of 1933–1945 in much greater detail, his book provides a deeper sense of how the German people’s intensely emotional hatred of the Jews ultimately led to mass murder. In contrast to Aly’s thesis, which ultimately universalizes the Holocaust by attributing it to a familiar and enduring human vice, Confino’s thesis provides a deeper analysis of the radically transgressive nature of the Nazi mission.

The only flaw in Confino’s penetrating work is his tendency to flirt with abstractions. While he skillfully shows how the Nazis pursued their own origin myth by attacking Jewish history and memory, he is less convincing in arguing that, in doing so, they were pursuing a rebellion against time itself. At various junctures in his book, Confino writes that the Nazis believed “the Jews represented time” in the sense of “evil historical origins”; that the Nazis wanted to create an “empire of time” in Eastern Europe by “destroying a key part of European civilization” as a means of re-forging it anew; and that they made the Jews a “people without time” by locking them in ghettos. These formulations are evocative, but are ultimately unnecessary.

Both Confino and Aly remind us of the centrality of anti-Semitism in the Nazi genocide. In doing so they correct the last generation’s tendency to explain the Holocaust as the result of universal, modern forces. What Aly and Confino remind us of so powerfully is that the Holocaust also resulted from the adaptation of historical hatreds to new circumstances.

Suggested Reading

Boundaries, Conversations, and the Reform Movement: A Response to Elli Fischer

Hebrew Union College dean Joshua Holo weighs in on Michael Chabon’s controversial commencement address.

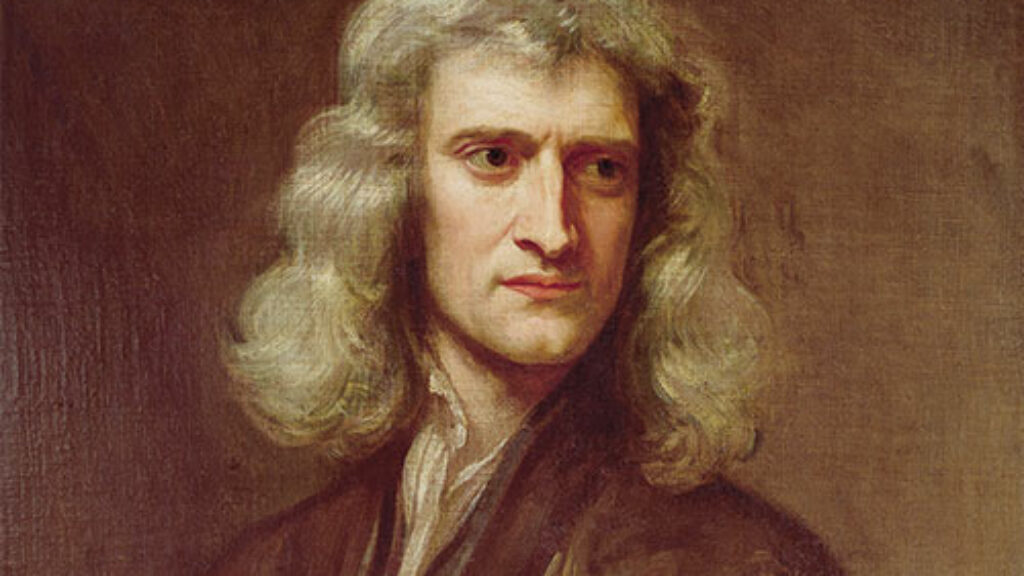

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

The Lost Voices of Salonica

Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s prodigious research, a true labor of love, gives voice to the long-silenced Salonican Jews.

Days of Redemption

Did early Zionists abandon Messianism or inherit it? Or, as Arieh Saposnik argues, did they do something more subtle and interesting?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In