Next Year on the Rhine

An American who wants to understand what the city of Worms has meant to the Jews of Germany might begin by thinking: Newport. Like the Rhode Island town, Worms is the quiet, waterside home of its country’s most venerable synagogue as well as an old Jewish graveyard that irresistibly plucks the “mystic cords of memory.” And much as Newport has symbolized for the Jews of the United States their early arrival on the American scene, Worms has for German Jews betokened their longtime presence on German soil. But the similarities don’t go any further.

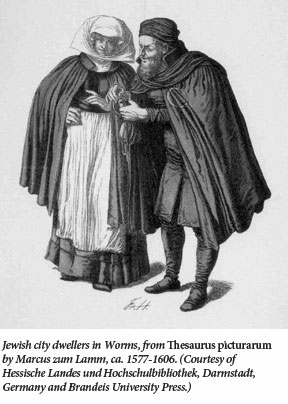

The American Jewish image of Newport is inseparably bound up with the famous letter in which President George Washington reminded the members of its Hebrew congregation that they lived under a government “which gives to bigotry no sanction” and “to persecution no assistance.” In the German Jewish mind, as Nils Roemer reminds us in his sweeping tale of Jewish Worms and the way in which it has been remembered and recorded, the image of Worms is always tied to recollections of the First Crusade, when mobs led by Count Emicho either killed or prompted the self-destruction of hundreds of the city’s Jews who were determined not to endure forced conversion to Christianity. And while the Jewish community of Newport never became famous for its cultural achievements, Worms was the temporary home during the 11th century of the great biblical commentator, Rashi, the dwelling place of the noted pietist Eleazar of Worms during the 12th, and both the birthplace and the final destination of the 13 th-century rabbinical authority Meir of Rothenburg.

But if Worms was a place of special significance for Jews already in the Middle Ages, it was so mostly in the minds of its own inhabitants. The horrible events that took place in the city in 1096 were commemorated for centuries by a special day of fasting—but only locally. New catastrophes in subsequent centuries added similar fast days to the calendar of Worms’ Jewry. For the city to acquire a unique importance for German Jews in general, it was first necessary for a united Germany to come into being, at least as an aspiration. Once it did, in the 19th century, and once the country’s Jews began to hope that they could fully belong to the fatherland, they revamped their understanding of their people’s history on German soil, drawing more distant from it in some respects and closer to it in others.

In Worms itself, the attitude toward the medieval martyrs underwent considerable change in modern times. Around 1815, at the time of German Jewry’s first steps toward emancipation, the local community cancelled the fast day that memorialized the martyrs of 1096. “Rabbi Koeppel of Worms approved the abrogation based upon a talmudic discussion that allowed the abolition of a previously accepted communal fast once the social and political conditions had changed.” By the end of the 19th century, Jewish historians working at the Central Archive of the German Jews in Berlin were viewing their people’s past through a thoroughly nationalist lens. For them, “Worms in particular seemed to reinforce the Jews’ claim of belonging in Germany even when most of them had moved to the big urban centers. Worms’ antiquity ornamented the notion that German Jews were one of the many German tribes (Stämme).”

This effort to utilize medieval Jewish history to authenticate the Jews’ German identity was not as pathetic as it may now sound. On the local level, it had plenty of Gentile support. There is, for example, the city archivist, August Weckerling, who “lamented at the 1883 conference of the Union of the German Historical and Antiquarian Societies the devastated status of Worms’ famous mikvah (ritual bath),” which he would eventually help to renovate. On the national level, at the same time, the historian Theodor Mommsen vigorously responded to anti-Semites with the assertion that the country’s Jews were one of its Stämme “no less than the Saxons, Swabians, or Pomeranians.”

Several decades and one world war later, in 1925, the city of Cologne organized a “Thousand-Year Exhibition of the Rhineland.” Introduced by Cologne’s mayor, Konrad Adenauer, it lavished attention on the Jews’ rich history in the area, displaying among other things “copies of important documents from Worms, Herbst’s photographs of the synagogue, and a model of Worms’ mikvah.” One of the major Jewish periodicals of the period hailed the exhibition for demonstrating that the “synthesis of Deutschtum and Judentum,” i.e., German-ness and Jewishness, was not just a Jewish idea. In such an environment, it is not too surprising to find a local lawyer, Siegfried Guggenheim, publishing a beautifully crafted haggadah in which he noted that his own family in Worms replaced the traditional conclusion of “Next year in Jerusalem” with the sentence “Next year in Worms-on-the-Rhine, our Heimat.” The celebrated Viennese writer Stefan Zweig hailed this volume as one that merited a place “at any German exhibition on the art of the book.”

But this spirit of concord would not last very long. The next major public celebration of the Rhineland Jewish heritage was the commemoration of the 900th anniversary of the Worms synagogue, which took place on June 3, 1934, more than a year after the Nazis took power. With a couple of exceptions, this was an all-Jewish affair, one about which the local press remained silent. For the Jews who were present, the worst aspects of the past had suddenly reacquired a disconcerting relevance. In his opening speech, the community’s rabbi, Isaak Holzer, “became almost defiant as he elaborated upon the religious devotion that had enabled the Jews of Worms to endure many challenges and even die as martyrs when necessary.” The leaders of Congregation She’arith Israel in New York, America’s oldest congregation, sent a message that showed that they were on the same wavelength: “In all the vicissitudes of its venerable history, from the martyrdom of the First Crusade to the sorrows of the present day, your community has withstood suffering with an unshaken faith and an unbroken courage that have been an inspiration to Jewish communities everywhere.”

Surprisingly, Roemer, a professor of Holocaust Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas, dwells only briefly on the rest of the dismal decade that followed the Nazi takeover. He provides us with some statistics pertaining to the number of Jews who emigrated in specific years, and he takes note of the deportation of the city’s last Jews in 1942, but his overall treatment of Worms’ Jewry’s worst years is cursory and sketchy. Roemer devotes some of his best chapters, however, to an account of the postwar efforts on the part of Jews and non-Jews alike to come to terms with the results of the Holocaust in Worms.

Of the more than five hundred Worms Jews who survived the Holocaust (out of a community of more than two thousand), very few came back to live there after the war. The story of postwar Worms Jewry therefore has more to do with relics than with people. The moveable ones—what survived of the community’s archives, manuscripts, and ritual objects—eventually came into the hands of the Israeli government, thanks to the intervention of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. It was Adenauer, too, and other German officials who were mainly responsible for pushing ahead with the plans to rebuild the Worms synagogue, despite the reservations or opposition of former members of the community, many of whom no doubt shared the feelings of Elke Spies. Writing in the New York-based Aufbau, Spies questioned who would benefit from the reconstruction: “Should these unscrupulous destroyers of Worms receive an object to view from which they can obtain income?”

Nevertheless, in 1961, around forty survivors of the community came from all over the world to participate in the rededication of what was to remain for a long time a tourist attraction, not a house of worship. As late as 1990, Cilly Kugelmann, co-editor of the German-Jewish journal Babylon, could complain in a radio broadcast from the synagogue’s Rashi chapel about the artificiality of reviving a synagogue in the absence of a local Jewish community. Since then, however, things have changed. Worms is now home to approximately seventy Russian Jews, some of whom conduct a service in the synagogue every couple of weeks. A number of them also belong to the Warmaisa Society for the Promotion and Preservation of Jewish Culture, a local, mostly non-Jewish group founded in 1995 that “hosts literary readings and organized lectures, seminars, concerts, and excursions to sites of Jewish history in Worms.”

Reading about the activities of the Warmaisa Society, one might almost imagine that the best aspects of the pre-Hitler era were somehow being retrieved and brought back to life. But no one can really pretend that this is the case, except on the very smallest scale. For the handful of Jews who have found refuge in the city, Worms can never serve as an anchor in the way that it did for generations of German Jews between the dawn of the era of emancipation and its unhappy culmination. Nor, of course, can it do so for the exiles and their descendants. When Siegfried Guggenheim published a revised version of his haggadah in 1960, by then in his new home in the United States, he “excised the reference to his family’s tradition of replacing ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’ with ‘Next year in Worms-on-the-Rhine, our Heimat,'” and inserted into the text not “Next Year in Flushing” (where he had settled), but best wishes to the State of Israel.

Suggested Reading

Always Messy: A Rejoinder to Andrew N. Koss

It may be useful as a tool for moral self-improvement to see oneself as adjudicating between opposing forces within one’s breast or brain, though where precisely the adjudicator, or charioteer, resides is more than a moot point.

Gut Shabbes

Upmanship & Downmanship

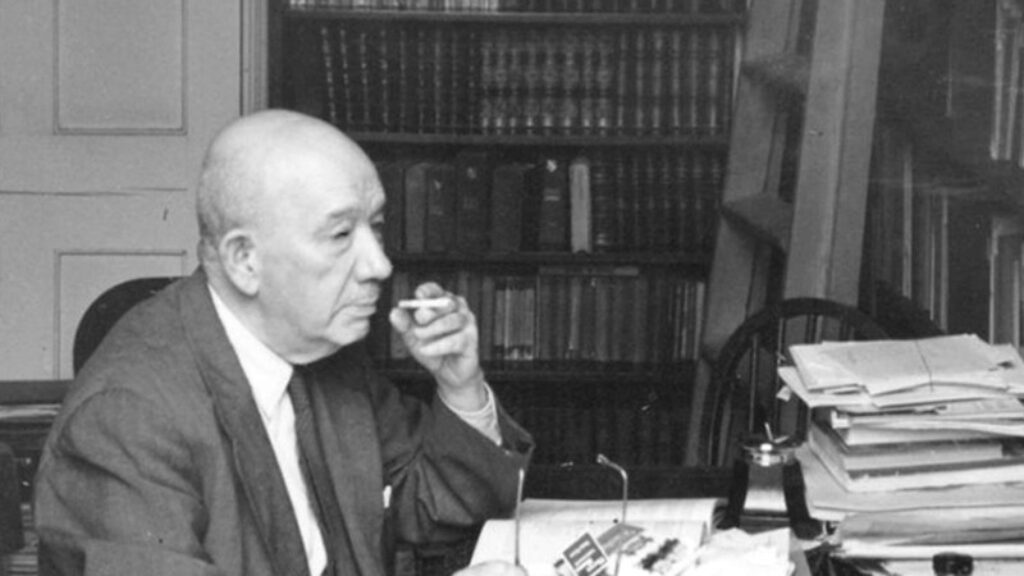

Between Antisemites and Zionists: The Path of Alfred Wiener

Alfred Wiener had a good nose for racial hatred and an impressive capacity to size up the German organizations that were spewing it out after World War I.

Lost Music

Jeffrey M. Green, Aharon Appelfeld’s translator for more than 30 years, remembers the beloved Israeli novelist.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In