Between Antisemites and Zionists: The Path of Alfred Wiener

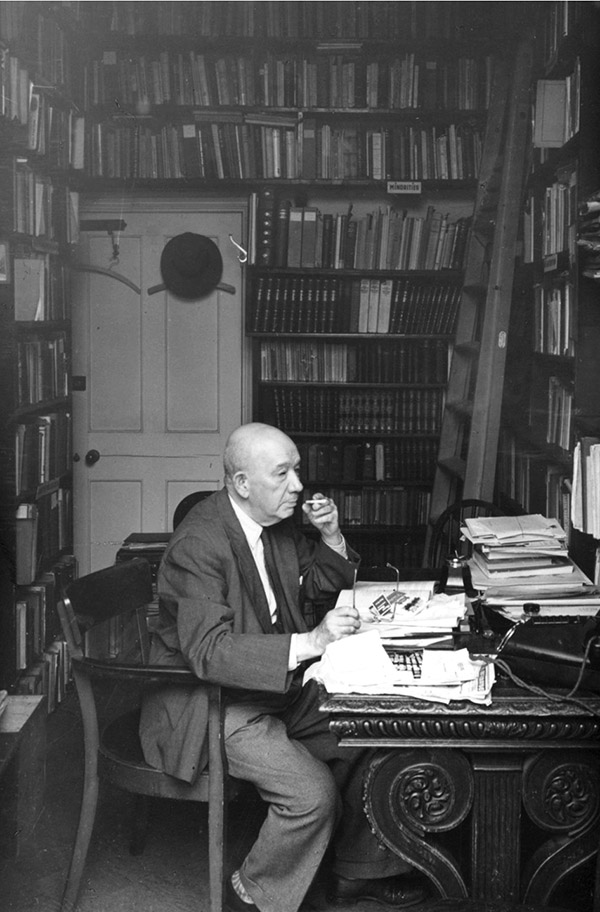

Few readers of Daniel Finkelstein’s new book are likely to know much about the Wiener Holocaust Library, much less its founder, Alfred Wiener. Even historians who read the Wiener Library Bulletin may not be acquainted with any part of the rich story Finkelstein has to tell about his maternal grandfather. A former executive editor of the Times of London and a member of the House of Lords, Finkelstein himself was two years old when Wiener died. In his deeply moving family history, however, he has brought his grandfather, as well as many other relatives, back to life. Two Roads Home: Hitler, Stalin, and the Miraculous Survival of My Family recounts the very different experiences before, during, and after the Holocaust of both his father’s family, Ostjuden from Galicia, and the Wieners, who were German Jews.

Finkelstein’s paternal grandparents, Dolu and Lusia, weren’t shtetl dwellers but wealthy urban sophisticates. They were Polish-speaking members of Lvov’s economic aristocracy (Dolu was known as the “Iron King”) who lived in a splendid Streamline Moderne villa on one of the city’s best streets and belonged to its cafe society. In 1939, the Soviets occupied Lvov, and the Finkelsteins were deported as Polish capitalists. Dolu was swallowed up in the Gulag, where he survived under brutal conditions until August 1941, when, like Menachem Begin, he was released to be recruited into General Anders’s Polish Army in exile. Meanwhile, Lusia and her then-eleven-year-old son, Ludwik, were dumped onto a Soviet state farm in eastern Kazakhstan. Reunited after Dolu’s liberation, the family followed General Anders’s army all the way to Palestine, where they had been sent under the British Middle East Command. The family stayed there until 1947.

Having abandoned hope of ever returning to their newly communized homeland, the Finkelsteins

accepted the British government’s offer to resettle in England. They did so, Ludwik later told his son, feeling “demoralised and defeated as Poles.” Nine years later, Ludwik met Alfred Wiener’s daughter Mirjam at a B’nai B’rith Youth Organization event. A year after that, the two were married. Wiener had been in Great Britain for two decades by that time, but his route there was, in its own way, as circuitous and traumatic as that of the Finkelsteins.

Born in Potsdam in 1885, Alfred Wiener spent most of his earliest years in a small town near the Polish border where his father opened a clothing store. When he was twelve, the family returned to Potsdam, a town he came to love deeply. His family was not traditional but, as Finkelstein puts it, “traditionalist”: they “would always have a Sabbath meal on a Friday evening, but the food would not necessarily be kosher.” Wiener himself seems at one point to have considered the rabbinate and spent some time studying at the Academy for the Science of Judaism in Berlin, but after traveling extensively in the Middle East, he pursued a different path and earned a PhD in Arabic literature.

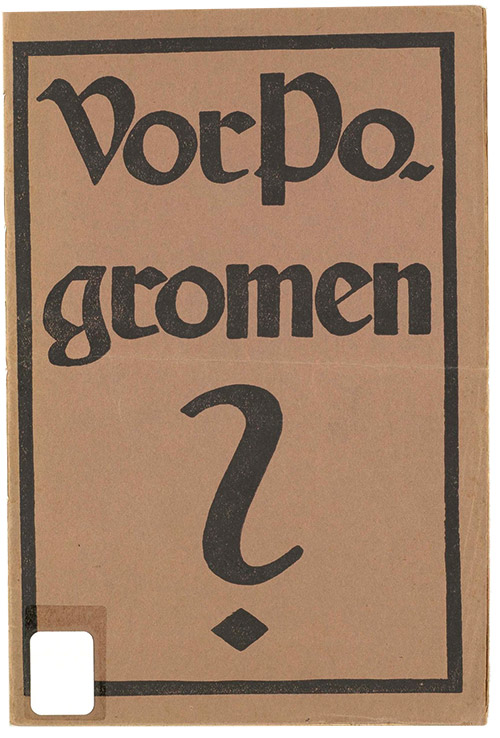

After his service in the German Army during World War I, which included a stint as a newspaper editor with the forces stationed in Palestine, Wiener found himself in a defeated country, in which he was much more attuned than others to the vulnerability of German Jews. This was, to be sure, a period of intensified antisemitism, aggravated by the infamous and spurious charge that Germany had lost the war because “the Jews stabbed it in the back.” Hitler, still just a rabble-rouser, and his ilk were making a lot of noise. There was the violent suppression of left-wing rebellions, in which Jewish revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg and Gustav Landauer were brutally murdered. Still, there were very few who felt, like Wiener, that German Jews were on the brink of experiencing the kind of violence that had plagued their fellow Jews in the Russian Empire for decades. In 1919, Wiener published a pamphlet titled Prelude to Pogroms? (It was translated into English in 2021 in a volume titled The Fatherland and the Jews: Two Pamphlets by Ben Barkow, a longtime director of the Wiener Holocaust Library).

Wiener had a good nose for dangerous racial hatred and an impressive capacity to size up the organizations that were spewing it out after the war. And he connected the dots. He warned his readers about the “‘men of action’ who state more or less openly in leaflets—and quite fearlessly at secret meetings—that they envy the Poles and Romanians their pogroms, and who work systematically to imitate them in our dear fatherland.” He pointed to the posters that had been spotted in German military barracks, one of which “showed a gallows and below it the words: ‘This is how you do it,’ and another the slogan ‘Throw them into the Red Sea!” Wiener understood that these were very bad omens. And “while widespread pogroms did not occur in Germany in the early 1920s,” as Michael Berkowitz observes in his introduction to Barkow’s volume, “antisemitism, including assault and murder, became firmly enmeshed in the political landscape.”

In the years to come, Wiener never dropped his guard. He became a key official of the emphatically non-Zionist Centralverein, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, an organization founded in the 1890s to combat antisemitism. As early as 1928, when Hitler’s share of the vote was still minuscule, he warned its executive committee that segments of the population were, as Finkelstein puts it, “particularly susceptible to Nazi propaganda.” In response, they set up a secret office that compiled a huge archive focused on the party. Wiener made the best use that he could of these documents as he crisscrossed Germany warning people of the Nazi threat.

In March 1933, within weeks of Hitler’s rise to power, Hermann Göring summoned Wiener to a meeting in which he demanded that the Central-verein destroy the documents it had used in its campaign against the Nazi Party. It did so, but that, of course, did not mean that Wiener was out of danger. In July, he left Germany for good.

Unlike tens of thousands of other Jews who fled the country that year, Wiener didn’t head for Palestine or even consider doing so. Wiener was, as Finkelstein makes clear, an opponent of Zionism, on both theoretical and practical grounds (as was the Centralverein). On the other hand, he was not altogether against Jewish settlement in Palestine. He even encouraged it. After a lengthy visit to the country in 1927, he wrote what Finkelstein calls his “most successful publication” Kritische Reise durch Palästina (A Critical Journey through Palestine), in whichhe expressly hoped that his own words would assist in the depoliticization of the settlement work already underway, thereby making it possible for every “Jewish German” to support it. “If you, Herzl’s disciples, will it,” he proclaimed, consciously echoing Herzl’s famous adage, “it is no legend.”

But what was the stuff of legend, to Wiener, was the idea that settlement on the land in Palestine could provide anything more than a modest, partial solution to the “Judennot,” the Jewish need, of the immiserated masses in the East. The country was simply too small, and too little of it was available. What had been accomplished since the 1880s didn’t come close to measuring up, in terms of square kilometers, to what had been achieved over the decades in Argentina or even with the Jewish agricultural colonies established by the Soviet Union, in collaboration with American Jewish philanthropies, in Ukraine and Crimea.

Wiener was impressed by the zealous idealism and strength of the young pioneers of the “communist-socialist” kvutzot in Palestine, but also suspicious. They seemed too unconventional, shambolic, and amateurish to prosper and too utterly lacking in faith. One has to ask, he politely but indignantly complained, “whether it is desirable that Judaism as a religion, precisely in the land of the forefathers, ought to be completely set aside.” In any case, the kvutzot couldn’t be anything more than transitional institutions. When they got older, Wiener said, their idealist founders were inevitably going to want more privacy and property for themselves (and one can’t say that he was wrong about this).

Wiener wasn’t impressed by the urban development of the Yishuv either. Tel Aviv, which had suddenly blossomed alongside Jaffa into a city of forty thousand, was among the most interesting phenomenon in the new Palestine, he acknowledged, but what was going to become of it? Its industrial base was weak, and there was just too little money around. “According to the dry numbers—and that’s what the capitalists rely on and why they withhold their funds from Palestine—one has to see the future of Tel Aviv in a dim light.” But, he adds, “everywhere one hears words of fresh hope: ‘Things will be fine!’”

Wiener clearly didn’t share this confidence (and here he can’t be credited with prescience), nor did he see success just around the corner for other grand Zionist projects. He visited Palestine only a year after the founding of the Hebrew University and was annoyed by what he called “the waves of propaganda” that that event had triggered. There weren’t any students at the opening, he observed, and there weren’t any now. What had been established was just a few research institutes, nothing that could by any stretch of the imagination be called a university. It would make more sense, Wiener strongly suggested, for German Jews to give priority to their own rabbinical and teachers’ seminaries, which were in dire need of funds and had a vital role to play in their religious and cultural life.

In view of his scholarly expertise, it is no surprise that Wiener gave abundant attention to what he labeled the “Arab question” in Kritische Reise durch Palästina. He succinctly summarized the communal tensions that existed in Mandatory Palestine and the altercations that had already occurred there but didn’t believe that—at the moment—the Arabs represented a real threat to the Yishuv. He warned, however, against underestimating them and foresaw the eventual emergence of a younger, better educated generation that would resist the Zionists more effectively. The efforts of Brit Shalom to promote a spirit of reconciliation with the Arabs did not escape his notice, but he was skeptical. “It will perhaps be possible,” he ventured, “to measure their success in another ten years” (by which time such efforts had become even more quixotic).

In the end, Wiener wished the Zionist enterprise well—but as long as it saw Palestine as the national home and cultural center of all Jews everywhere and regarded German Jews as people living in exile, he insisted, “the Jewish German” ought to keep his distance. “For we must remain in heart and will Germans and Jews, since we cannot do otherwise. If we tear ourselves out of our German people, then our Germanness and our Jewishness will collapse.” For the “disciples of Herzl” Wiener addressed so cordially at the beginning of his book, he had, by the end, few favorable words.

In 1919, Wiener had predicted pogroms in Germany, but he didn’t smell any imminent danger in Palestine in 1926. So, when the pogroms did come in 1929 in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and other parts of the country, he couldn’t say I told you so. But by the end of the year, he had published a new fifty-page booklet, Juden und Araber in Palästina (Jews and Arabs in Palestine), in which he attempted to account for what had just happened.

Given his overall orientation, one might have anticipated that Wiener would draw the same conclusion as another Central European intellectual, Hans Kohn, who at that very moment was counting himself out of a Zionism that could only survive if it were protected from its Arab enemies by bayonets. But what he did instead was to blame not one side or the other but “the fanatics on both sides.” On Wiener’s account, Revisionist chauvinists had fanned the flames of a dispute over the Western Wall, asserting the Jewish right to the holy site in a way that inspired irrational fears and behavior on the part of the Arab masses whose rage, once aroused by their leaders, “knew so few limits, as we have just learned from the awful events in Hebron and Safed.”

In blaming the Revisionists, however, he did not let the rest of the Zionist movement off the hook. Nationalism was, he declared, “a wine that one cannot drink without consequences,” and even the idealistic type, upheld by some admirable Zionists, was prone to decay into the “vulgar, combative, imperialistic” sort represented by Jabotinsky and the Revisionists.

What could be done, then, to repair the damage and ease the tensions in Palestine? Wiener had a few suggestions. He regretted, for instance, that the Zionist executive hadn’t done a better job in the past of digging a deep ditch between itself and the Revisionists and hoped that this mistake could be corrected. He likewise anticipated that “the Jewish Agency will now finally undertake energetic, well considered efforts to bring about an understanding between Jews and Arabs.” But he was beset, he wrote, by the crippling doubt that any such efforts would remain fruitless unless the basic assumptions of both the Zionists and the Arabs underwent fundamental changes. Still, he hoped for some kind of compromise, and that “a way would be found to bring peace and happiness to the Holy Land, soon and forever.”

When Wiener fled Göring and the ascendant Nazis in the summer of 1933, he still kept up the fight against antisemitism. From Amsterdam, with the assistance of Jewish organizations across the world, he recommenced his archival labors and built what Finkelstein calls “the world’s most important—the world’s only—centre of anti-Nazi propaganda and research,” the Jewish Central Information Office. Finkelstein describes their work:

[It] circulated reports to Jewish organisations, human rights pressure groups, journalists and governments worldwide, providing factual information about Nazi activities—speeches by Goebbels, the latest outrageous libel in Der Stürmer, the most recent absurd and poisonous piece of Nazi “scientific research,” on the “alien nature” of the Jew, and so on. It did so with a minimum of comment, allowing the material to speak for itself.

In 1934 and 1935, Wiener and his office assisted massively in the once-famous Bern Trial of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, doing research for the Swiss team that sought to expose the work as a complete hoax. They continued to assemble and circulate information about the Nazi regime’s crimes to the world press until, after Kristallnacht, the Dutch government began to fear that Wiener’s activity would endanger their neutral status. Wiener, together with some of his staff, moved the operation to London—just in time.

Just in time, that is, to keep his files intact, but not his family. His wife and daughters couldn’t get the necessary papers before the Nazis invaded and had to face the horrors without him. They spent the war years in the grim world from which Anne Frank (who first appears in Finkelstein’s narrative as the younger sister of his aunt Ruth’s friend Margot) had been hidden. Wiener worked tirelessly from afar to get them out, but he couldn’t prevent their deportation to Belsen, where, in December 1944 Ruth got her last glimpse of Margot and Anne Frank, who “looked pretty terrible.” All of the Wieners would no doubt have met the same fate as the Frank sisters had Alfred not ultimately succeeded, in January 1945, in wangling them onto a small list of Jewish captives who were exchanged for German-born civilians who had been interned overseas. Unfortunately, Alfred’s wife, Grete (a heroine in her own right), was too ill to survive her transfer to Switzerland for even a day. But the couple’s daughters soon rejoined Alfred in New York.

Throughout the war years, as the female Wieners suffered in the Netherlands and in the camps, and as Finkelstein’s other forebears struggled to survive in the East, he continued his anti-Nazi work, at first in Great Britain and then, after August 1940, in New York City. There he worked with American and British intelligence and funneled information from his office to carefully identified sectors of the American public to remind different ethnic groups of what the enemy was like and to help sustain support for the war.

In 1927, Wiener had been appalled at the very idea of German Jews trying to tear themselves out of Germany. Two decades later, after he had been forcibly removed from it, he showed no desire to return. Not to live, anyhow. But in the early fifties, he began to visit Germany to speak to the younger generation about what had happened and what the country had once stood for. “Their enthusiasm and commitment,” Finkelstein tells us, “made him feel that his idealistic view of Germany had contained truth within it, even though his own generation had betrayed him so badly.”

The West German government awarded Wiener its highest civilian decoration in honor of these efforts. Still, Wiener no longer believed, as he once had, in the fusion of Germanness and Jewishness, nor did he continue to oppose Zionism. “After the war,” his grandson notes, “he embraced wholeheartedly the idea of a Jewish state in Israel.”

Wiener didn’t show any interest in living there, however. Returning from America to England in 1945, he devoted himself to the preservation of his library, a task rendered difficult by the British government’s abrupt cutoff of funding to an institution for which it no longer felt it had any practical need (but which subsequently proved to be a major help in preparing for the war crimes trials at Nuremberg). He met this challenge too. While never completely escaping financial difficulties, during Alfred Wiener’s lifetime—he died in 1964—or thereafter, the Wiener Holocaust Library has continuously served as a key resource for generations of scholars and students of the Holocaust.

Suggested Reading

Revolution, the Jews, and Hitler’s Munich

How did a Jewish Socialist become the revolutionary leader of the People’s State of Bavaria? And did his brief career provoke the rise of Hitler?

George Lichtheim’s Marxmanship

The brief, wondrous life of a renegade intellectual.

Counting Jews

Tim Grady makes a careful but controversial case about the way Jews contributed to or supported Germany's worst excesses in World War I.

History of a Passé Future

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In