Vegetarian in Vilna

What do Jewish foodies talk about when they talk about food? “Meatless mains” to judge by several recent kosher cookbooks. So when one reads in another new kosher cookbook that “It has long been established by the highest medical authorities that food made from fruits and vegetables is far healthier and more suitable for the human organism than food made from meat,” it would be reasonable to assume that the author is a contemporary.

But what seems new turns out to have been merely forgotten. The author was Fania Lewando, the chef and owner of Vilna’s Vegetarian-Dietetic Restaurant in pre-Holocaust Poland. In her 1938 cookbook, she endearingly addresses this advice “tsu der baleboste,” to the housewife. The original date and place of publication can’t help but give the reader retrospective shivers. Yet its appearance in print this spring, in a handsome American edition with a meticulous English translation from the original Yiddish by culinary ethnographer Eve Jochnowitz, and an introduction by noted food writer Joan Nathan, speaks to the sustaining role food plays in keeping culture and memory alive. It also turns out to be a triumph of perseverance.

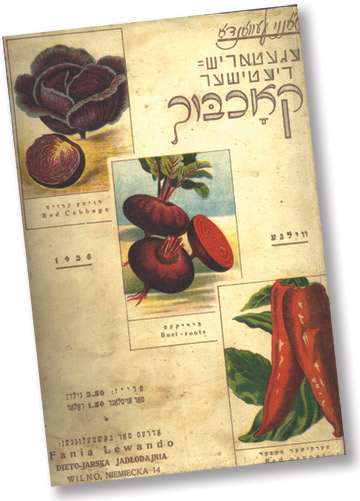

Six years ago, while participating in a book group at the library of New York’s Institute for Jewish Research (YIVO), Barbara Mazur and Wendy Waxman were drawn to an unusual book on display. Its cover featured vivid illustrations of beets, red cabbage, and red peppers, lusciously pictured as if just harvested from the ground. It turned out to have been among the few remaining copies of the original Yiddish edition of Lewando’s book, donated to YIVO in 1995 by a couple who had happened upon it in an antiquarian bookshop in England. Lewando’s book had never been translated into English (or any other language), but Mazur and Waxman made it their mission to bring it to an American audience. After raising the money for a translation, they cornered Joan Nathan at a lecture. “As soon as I saw it, I realized that they had discovered a piece of Jewish culinary history that must be told and shared,” Nathan writes in her introduction. She passed it along to Altie Karper, editorial director of Schocken Books, and 77 years after its original composition, Vegetarish-Dietisher Kokhbuhk (as its Yiddish title reads) is now available in English translation.

Fania Lewando, known to her family as Feige, was born in northern Poland in the late 1880s. We learn from an essay contributed to the book by Lewando’s great-nephew Efraim Sicher that she remained in Eastern Europe even after her parents and three of her siblings left for England in 1901. Even before that, two other sisters had already departed for America. In time (the year is not mentioned) she married Lazar Lewando, a Belorussia-born egg merchant, and they moved to Vilna, where she became a prominent chef, restaurateur, and proponent of vegetarianism. From 1936 until 1939, Lewando supervised a kosher vegetarian kitchen aboard a luxury liner whose route ran from the Polish port of Gdynia to New York. One wonders if she attempted to stay behind, rather than return to Europe. In any event, she could not. In 1920 Lazar had been arrested by the Soviets as a bourgeois capitalist and was wounded in the leg during his escape, and the old injury was apparently used as a reason to deny the couple an immigration visa. She was also unsuccessful in her efforts to interest the H. J. Heinz company in her recipes and get a job with the company’s English division.

Lewando’s cookbook is a revelation. Certainly, the long, brutal winters and meaty cuisine of Eastern Europe don’t immediately make one think of garden-fresh vegetarian recipes. Yet she was not the only Yiddish-speaking advocate of the vegetarian diet, as demonstrated by two essays she included by like-minded contemporaries. The first (which she excerpted from a longer article by a Dr. B. Dembski) rather stiffly explains the scientific basis for the health benefits of vegetarianism. The second essay, “Vegetarianism as a Jewish Movement” by Ben-Zion Kit, is more interesting:

It is worth noting that, according to the Bible, the first permitted foods were plants. In Genesis 1:29 it is written: “And God said, ‘I give you all seed-bearing grasses that grow on the earth and all trees that bear fruit and this shall be for you to eat.’” Meat became permitted only after the flood, when there were not yet any new plants to eat.

In her introduction, Lewando similarly invokes the Jewish vegetarian-humanitarian prohibition against causing “tsar baaley khayim,” or pain to animals.

Lewando’s restaurant was apparently popular. Marc Chagall and poet Itzik Manger signed the guest book, excerpts from which are included in the cookbook’s appendix. In her memoir of her pre-war sojourn to Vilna, From That Place and Time: A Memoir 1938–1947, historian Lucy S. Dawidowicz, best known as the author of The War Against the Jews: 1933–1945, specifically mentions the restaurant. But like so much else from that time and place, relatively few additional details about Lewando, her restaurant, or her cookbook seem to have survived. Of the 57,000 Jews who lived in Vilna in 1939, by the end of World War II, only between two thousand and three thousand remained alive. Lewando and her husband were not among them, having disappeared in 1941 after a failed attempt to flee from the Nazis.

With such retrospective knowledge, it was impossible for me to begin my kitchen prep without noting a subtext beneath the recipes that seemed to encode the anxieties and concerns of a community at the precipice. “Throw nothing out,” Lewando admonishes the reader in italics, “everything can be made into food.” How scarce was food in pre-war Vilna? During her 1938 stay Dawidowicz noticed that “Green vegetables were scarce and expensive,” and many other market items were only available at high-priced luxury stores. As a result, she ate mostly “root vegetables—potatoes, carrots, beets, onions and dried legumes. Milk wasn’t pasteurized and had to be boiled. Coffee was terrible, made of chicory and who knows what else.” As for meat, starting in 1935, kosher meat had become increasingly scarce with ever-stricter laws limiting the practice of shechitah, the Jewish ritual slaughter of meat and poultry, though, needless to say, that would not have undermined Lewando’s menu.

But many Jews could not afford to buy any food at all. “In the [Depression] New York I knew, I seldom saw people as pitiably poor as those in Vilna,” Dawidowicz wrote of the squalor she witnessed. Israel Cohen, in his 1943 volume Vilna, noted that “So widespread was poverty within the Jewish community that it was commonly estimated that at least three-fourths were dependent upon some form of relief.” Beggars, he wrote, “haunted the doors of restaurants and cafés,” adding in a footnote, “Once when I sat at the open window of a café, I was approached within ten minutes by six persons in turn—from an old man to a young child—all appealing timidly for bread.”

This backdrop of scarcity helps to explain Lewando’s thrifty advice:

don’t throw out the water in which you have cooked mushrooms or green peas; it can be used for various soups. Don’t throw out the vegetables used to make a vegetable broth. You can make various foods from them, as is shown in this cookbook.

To be sure, it is common for cookbook authors to oppose waste, but Lewando’s insistence is extreme, as if life itself depended on leaving no stale crust or crumb of challah behind (and given the conditions then, and what was to come, it might well have).

But amid the poverty, there apparently remained enough patrons to keep Lewando’s restaurant (and cruise ship) afloat. And her cookbook pantry is far from empty. Her recipes—and as the original Yiddish subtitle declares, there are 400 of them—call for what seems like whole cellars full of beets, carrots, rutabaga, celery root, potatoes, onions, and garlic; barrels full of cabbage and cucumbers; bushels of tart apples and pears and berries when available; fresh greens in season; a broad range of beans and nuts; and more sacks of barley and flour larger than you’d find at Costco. Dill (whether fresh or dried) is her herb of choice, and mushrooms, also both fresh and dried, are used frequently. All these combine to cook up a rich and tasty traditional Central/Eastern European/Ashkenazi cuisine featuring a mind-boggling assortment of kugels, schnitzels, stews, soups, dumplings, borscht, latkes, puddings, cholents, frittatas, savory pies, porridges, stuffed vegetables, breads and cakes, jams and preserves, and beverages, both alcoholic and not.

“People ask, ‘where’s the kale?’” Eve Jochnowitz told me in an interview after the book launch. “But cabbage has almost all the superpowers that kale has. And it is thanks to sauerkraut that so many of us of Eastern European descent are alive today, because that was the only source of Vitamin C during those cold winters.” One of Jochnowitz’s favorite recipes from the book is an unusual “pickle soup” that brings together sour pickles, potatoes, carrots, marinated mushrooms, and green peas, garnished with sour cream and chopped fresh dill. The result, she says, is “a combination of sourness and

richness.”

Lewando’s detailed instructions for pickling and preserving also reflect an era that predated contemporary refrigerator-freezers, not to speak of today’s more general reliance on the vast assortment of supermarket jarred pickles and preserves that go way beyond Heinz’s original 57 varieties. But the re-publication coincides with a renewed interest in small-batch pickling and preserving. Adventurous foodies might try “Radish Preserves,” which entails cooking long thin slices of black (or daikon) radish in a sugar-and-honey solution and then adding chopped toasted walnuts and diced candied orange peel.

Today’s cooks may also wonder at Lewando’s very generous use of butter, eggs, and always full-fat milk and cheese. Clearly, this is not a vegan cookbook (in today’s terminology, Lewando was a lacto-ovo vegetarian), and it pre-dates our current era of cholesterol-consciousness. In her introduction, Nathan recommends that cooks today who seek “healthier alternatives” consider substituting cream with yogurt. For a taste that is less tart, I would also suggest trying part-skim or non-fat ricotta cheese. And olive oil, instead of butter, works well with the many cutlet recipes (spinach, cauliflower, mushroom, and beans among them), which might be thought of as Vilna-style home-made veggie burgers.

There is one more hurdle modern cooks may encounter in trying out Lewando’s recipes. In contrast to the lengthy, step-by-step instructions we’ve gotten used to, Lewando’s recipes are, in the style of the time, concise, almost elliptical, explaining in two or three sentences what more typically today would probably take a full page (and maybe a linked video) to spell out. Throughout, however, Jochnowitz’s annotations anticipate and answer questions that may arise about a cooking procedure or possible variation or substitution.

The range and sophistication of Lewando’s recipes were on display at the launch party in celebration of the book in early June at the New York headquarters of YIVO (its original headquarters were in Vilna). The menu, selected and prepared by The Gefilteria and The Center for Kosher Culinary Arts, began with an elegant “Cold Blueberry Soup,” continued with “Leek Appetizer,” “Egg Stuffed with Marinated Mushrooms,” “Eggplant Appetizer,” and “Rye Flour Honey Cake.” And to wash it all down was a seltzer spritzer flavored with a sugar-enhanced rhubarb syrup made following Lewando’s technique for beet juice and carrot juice.

In addition to “reaffirming so many food traditions,” The Gefilteria co-owner Jeffrey Yoskowitz said he admired Lewando’s resourcefulness, as exemplified in finding so many uses for stale challah (in everything from appetizers to kugels), as well as her imaginative use of ingredients. The recipes also lent themselves to contemporary updates and creative touches, he found. He added heft to the blueberry soup, for example, by not straining the blueberries as Lewando called for and by adding a dash of lemon zest to give the zing that our less flavorful berries today tend to lack. He also lightened the leek appetizer by eliminating additional hard-boiled eggs called for in her original recipe. In an inspired touch, the eggplant appetizer became a kind of bruschetta, served on melba toast (though I suspect Lewando herself might have preferred stale challah slices).

As for the rye-flour honey cake, this Rosh Hashanah I plan on adding it to my menu. As Lewando suggested, I’ll also fill it with one of her fruit jams. And maybe on Sukkot, I’ll pour a glass of fortified “Spirit Liqueur” and toast l’chayim—these recipes still live.

Suggested Reading

A Sharp Word

From his intensive study of Hebrew and Jewish history to a surprisingly romantic Zionist congress in Basel, and the horrors of the Kishinev Pogrom, 1903 seems to have been a turning point for the young Jabotinsky.

Killer Backdrop: A Response

Erika Dreifus expresses dismay over Amy Newman Smith's essay on Holocaust fiction.

On Re-Reading a Banned Book: Nathan Kamenetsky’s Making of a Godol

Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky spent years on an odd, brilliant biography of his father. The book was banned, and one leading haredi rosh yeshiva said he had forfeited his share in the world to come. Now it is an underground classic that costs $2,503 on Amazon.

Israel on the Hudson

An ambitious, new three-volume work attempts to tell the story of New York's Jews from the days of Peter Stuyvesant to the present.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In