Israeli Strategy for a New Middle East

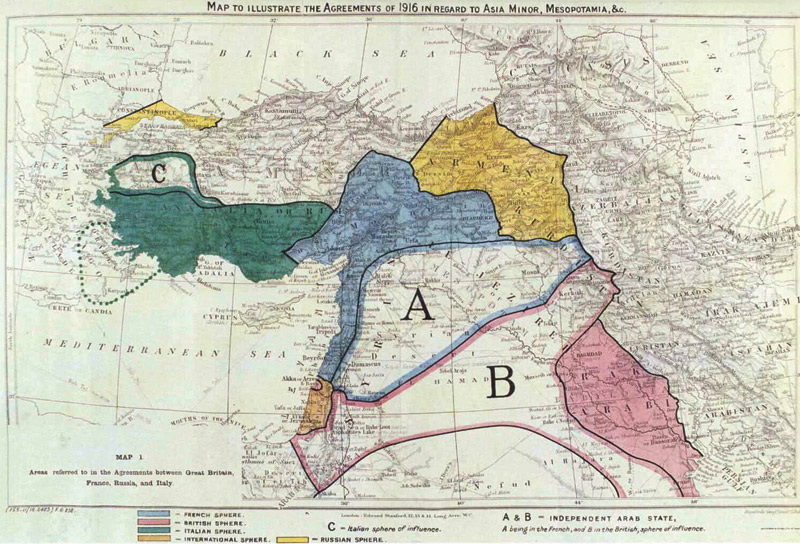

Until World War I, a large part of the Arab population of the Middle East lived in the outlying provinces of the ailing, soon-to-be-defeated Ottoman Empire. In 1916, while the war was still going on, the British troubleshooter Sir Mark Sykes and the French diplomat François Georges-Picot negotiated a secret agreement that reallocated this territory. They established British and French zones of influence within which Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan would eventually take shape, as well as a short-lived plan for an international condominium over Palestine. The borders they drew were based on neither geography nor culture. Instead, they bound together fragments of ethnic groups and faith communities that had little in the way of a shared identity.

Nevertheless, for almost a century, these artificially created Arab states survived, mostly due to the ingenuity and brutality of their potentates—first kings, then generals. Rulers who belonged to ethnic or religious minorities, such as the Sunnis who ran predominantly Shi’ite Iraq, the Alawites who ran chiefly Sunni Syria, and the Hashemite rulers of mostly Palestinian Jordan, resorted to the idea of nationhood in order to bridge the ethnic and religious fault lines that divided them from the populations under their control. Over the last few years this system has begun to collapse. This is true not only in the countries that owe their specific existence to Sykes-Picot, such as Syria and Iraq, but also in Yemen, Libya, Sudan, Bahrain, and beyond.

As these Arab states crumbled, a host of forces has stepped into the breach: the nearby, non-Arab nation-states Iran and Turkey; non-state actors (very much including the so-called “Islamic State,” or ISIS); as well as several non-Arab ethnic groups, such as the Kurds and Druze. This is the new strategic landscape in which Israel must maneuver. Moreover, it is within the context of this suddenly fluid Middle East that Israel must evaluate the Vienna Nuclear Accord or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) recently negotiated between the P5+1 powers (the United States, China, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany) and Iran.

Apart from Israel, there are now only three solidly grounded nation-states in the Middle East: Iran, Egypt, and Turkey. Neither Iran nor Egypt owes its existence to Sykes-Picot, while Turkey basically consists of the Ottoman Empire minus the territories targeted by the British-French agreement. Each of these three states has a clear national identity, national solidarity, and the ability to function effectively, despite internal challenges and even, in some cases, regime change. During the years that the Muslim Brotherhood ruled Egypt, for instance, the Morsi administration made it clear that it placed “Egyptianness” before the call to supranational Islamic revolution. Indeed, the Morsi government was surprisingly pragmatic in the pursuit of Egyptian national interests. We can assume that in the new Middle East, these three nation-states, together with Israel, will remain the pivotal actors. It is this new strategic fact that makes Israel (and, for that matter, Egypt and Turkey) so apprehensive about the ways in which the JCPOA are likely to strengthen Iran.

The other group of sovereign entities in the Middle East consists of a cluster of monarchies: Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the Gulf principalities. Each of them has a looser sociopolitical structure, a weaker sense of national identity, and less internal coherence than Egypt, Iran, Turkey, or Israel. Saudi Arabia warrants special attention, since it is the last of the Sunni Arab powers with aformidable capacity to hold the Arab line against the emerging forces and threats. Historically, Saudi Arabia has preferred to apply soft power behind closed doors and has left it to others to play the frontal roles in regional struggles. Yet, as the United States steps back from policing the region, as Iraq no longer counterbalances Iran, and while Egypt is preoccupied with its own internal difficulties, Saudi Arabia is the only power equipped to defend Bahrain and Yemen from a takeover by Iran’s proxies, to sustain its own clients against those of Iran and Turkey in the proxy battles for Syria and Iraq, and to combat ISIS from the Sunni Arab corner.

Both within the region carved up by Sykes and Picot and beyond it, in other failed or failing states, non-state actors now hold unprecedented power. These include Shi’ites, Sunni Arabs, and other non-Arab ethnic groups. Most Shi’ite non-state actors enjoy some sort of client-patron relationship with Iran. This provides them with a qualitative edge in weapons, training, and funding. In return for this assistance, they fit their actions, for the most part, into an overarching Iranian strategy. They are basically cogs in an Iranian-Shi’ite supranational apparatus.

The Sunni non-state actors can be divided into those that have distinct territorial or ethnic connections and those that are “global” or non-national. Some aspire to take over a country while preserving it within its distinct historic boundaries, while others seek to draw new borders or form a faith-based non-national caliphate. Some benefit from state patronage, while others act independently. The most prominent Sunni non-state actor currently on the scene is, of course, ISIS. The organization’s “success” has been achieved in the vacuum that states such as Syria and Iraq have left behind them. This vacuum is a result, in part, of the weakness of Sunni civil society, the absence of an empowered middle class, and, to a degree, Sunni fears of a Shi’ite takeover. ISIS’s potential is thus limited to such dysfunctional Sunni areas, and it will probably not be able to overpower a competent state (though it could cause civil unrest in weak Sunni states). Even if ISIS is defeated, however, the ecosystem in which it arose will remain in place, setting the stage for the emergence of another (if perhaps less flamboyant) ISIS-like organization.

Finally, the collapse of the state system in much of the Middle East has strengthened historically subjugated ethnic groups such as the Druze and the Kurds. Given their internal coherence, solidarity, and shared identity, it is not impossible that some of these groups may become full-fledged nation-states.

This region criss-crossed with fissures is no longer the Middle East to which we have long been accustomed, one that had to be viewed through the lens of the Israeli-Arab conflict. Some of Israel’s archrivals, such as Syria, Iraq, and Libya, barely exist at all. Most of the surviving Arab states (Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia) are Israel’s de facto allies in the struggle against state and non-state common enemies—led by Iran. Entities such as Hezbollah have to be considered in an Iranian—not Arab—context. Of the broad Israeli-Arab conflict little remains but the Israeli-Palestinian one.

The principal nation-states of the new Middle East—Israel, Egypt, Turkey, Iran, and, at least for the time being, Saudi Arabia—do not share many contentious borders. Israel and Egypt now collaborate against Hamas and Sunni jihadists in the Sinai Peninsula, and the border between Turkey and Iran is mountainous and hundreds of miles away from the nearest point of real value. So where are the rivalries, competitions, and threats?

At least three categories of forces are on the rise, attempting to change the regional system to their advantage. First and most notable is the Shi’ite supranational system, orchestrated by Iran. In past centuries, Iran was a nation that mostly sought to defend itself against the menace posed by greater, outside forces. With the collapse of the Soviet empire, new, unthreatening Muslim states now constitute a buffer between Iran and Russia. Moreover, Saddam Hussein is no longer on the scene threatening an Arab invasion; Turkey is somewhat directionless; and the United States has withdrawn from Iraq (Iran’s western neighbor) and is withdrawing from Afghanistan (its eastern neighbor). Benefiting from this power vacuum, Iran has become, through its proxies, the dominant factor in four Arab capitals: Damascus, Baghdad, Beirut, and Sana’a. Meanwhile, Iran is also inserting itself into Bahrain, eastern Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Eritrea, Gaza, and a host of central Asian theaters.

Iran is also on the verge of expanding its power considerably as a result of the JCPOA. It will apparently maintain sufficient capabilities to break out to a bomb at a time of its choosing and to build the means of delivering nuclear weapons to their targets. The lifting of sanctions against the country, moreover, will reenergize its economy with an influx of at least $120 billion. And while Iran’s expansion has managed to mobilize almost all regional players against it, JCPOA would seem to open the possibility of an Iranian rapprochement with the United States and the West.

Other forces seeking to reorganize the regional system in their favor include the rogue non-state actors, as well as Turkey and Qatar, which seems to play on several teams simultaneously. One may therefore draw the primary fault lines in the Middle East between four groups of competing actors: the Iranian-Shi’ite camp, Turkey, a host of Sunni jihadists (not in one camp), and, finally, the surprising de facto coalition defending the status quo: Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the other monarchies.

At the moment, the main bones of contention in the Middle East are the territories of three failed states: Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. Everyone—the Shi’ites, the Turks, and various Sunni jihadists, as well as Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—has vital interests in these countries, and all these countries are engaged in action in at least one of the three failed states in one way or another. With the stability of Jordan, Bahrain, Lebanon, and possibly even Saudi Arabia itself in some jeopardy, the future of these states, too, is at stake. Iran is, again, the most aggressive of the regional forces, with a dog in almost every fight.

Apart from these zones of competition, there are offshore issues, mainly with regard to the Straits of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb, as well as the eastern Mediterranean gas basin. The latter is mostly still under development, yet it is already clear that it is one of the largest recent gas finds in the world. Most of the existing and potential gas fields are located in either Israeli or Greek-Cypriot waters, as divided in an agreement between these two governments. The Lebanese and the Turkish-Cypriot governments are contesting this agreement, with the latter enjoying the support of Turkey. It is still unclear whether Israel will supply gas to Egypt, the Palestinians, Jordan, and perhaps even Turkey, or whether Turkey will continue to challenge current arrangements. It is also unclear whether central Asian rivalries between Turkey and Russia (something of a patron of Greek Cyprus) will spill over into the eastern Mediterranean. What is exceedingly clear is that a new, highly valuable asset has emerged at the meeting point of several regional competitors.

The Suez Canal has long been the object of international competition, yet all traffic heading to or from the canal must also pass through the Red Sea and the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb. Recently, Iran has attempted to establish its presence in this narrow seaway, both on its western shore (Eritrea, Sudan) and on its eastern shore (Yemen). If Iran succeeded in getting a grip on the Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb, it would gain significant leverage over both Egypt and Israel while controlling Jordan’s sole maritime access. Almost all Saudi and Gulf oil also passes through either Hormuz or Bab el-Mandeb (or both). If Iran were to gain even a partial grip on all of this traffic, it would entail great dangers.

Another threat to regional stability stems from the growing presence of nuclear and chemical capabilities. The JCPOA has, in effect, legitimized Iran’s previously unacceptable nuclear program and left the Islamic Republic with sufficient capabilities to sustain and expand it. In a best-case scenario, JCPOA would regulate and slow down Iran’s crossing of the nuclear threshold, but in a worst-case scenario Iran would use its remaining nuclear capabilities to covertly break out to a bomb. In any case, JCPOA will provide other regional powers with a strong incentive, and implicit international legitimation, to develop their own nuclear programs.

The repeated and, by now, almost routine use of chemical weapons in Syria’s civil war means that important psychological and political lines have been crossed, even if the arsenals are on all sides, for the moment, fairly rudimentary. As advancing technology makes such weapons and their means of delivery more accessible, even non-state actors may be capable of subjecting population centers hundreds of miles away to poisonous attacks. Indeed, ISIS is reliably reported to have recently used mustard gas in both Iraq and Syria.

What should be evident from all of this is that the state system that Sykes and Picot helped to create almost a century ago no longer exists, and consequently Israel’s strategic map has changed beyond recognition. Old adversaries have disappeared or been transformed, and new ones have emerged. Fault lines and the objects of competition have shifted. And technological advances have both increased the impact of hideous weaponry and the dispersal of capabilities previously possessed only by highly competent powers. Rocket science is no longer “rocket science.”

The Middle East in which Israel took its place in 1948 was one that had been largely shaped by the intervention of Western powers, and through most of the decades of its existence powers external to the region, especially the United States, have played a major role in determining what happens there. But America has been badly burned by its recent efforts in the Middle East, is apparently becoming less dependent on the region’s oil, and seems to be moving in a more isolationist direction. It is not unfair to ask whether the Obama administration still sees the world in terms of sustaining a wall of allies against an axis of foes, or whether it has concluded that it is more cost-effective to reach a strategic equilibrium with those foes.

Perhaps a sign of things to come was the exclusion of the American secretary of state from the diplomatic process that terminated the Gaza conflict of 2014. Secretary Kerry, in consultation with Turkey and Qatar, stuck to a position that was rejected by all of America’s historical allies in the region. As a consequence, the regional forces themselves—mostly Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—resolved the conflict on their own, excluding the United States from the process. Nothing like this had happened before. But on an increasing number of issues—from the Syrian chemical weapons crisis to Israel’s call for support of Egypt’s President al-Sisi to the present controversy over the Iran accord—Washington and Jerusalem are reading from different pages. Whether these differences will persist beyond the current American and Israeli administrations is impossible to say. What is clear is that the Middle East has changed and will likely continue to do so at a rapid pace.0

Suggested Reading

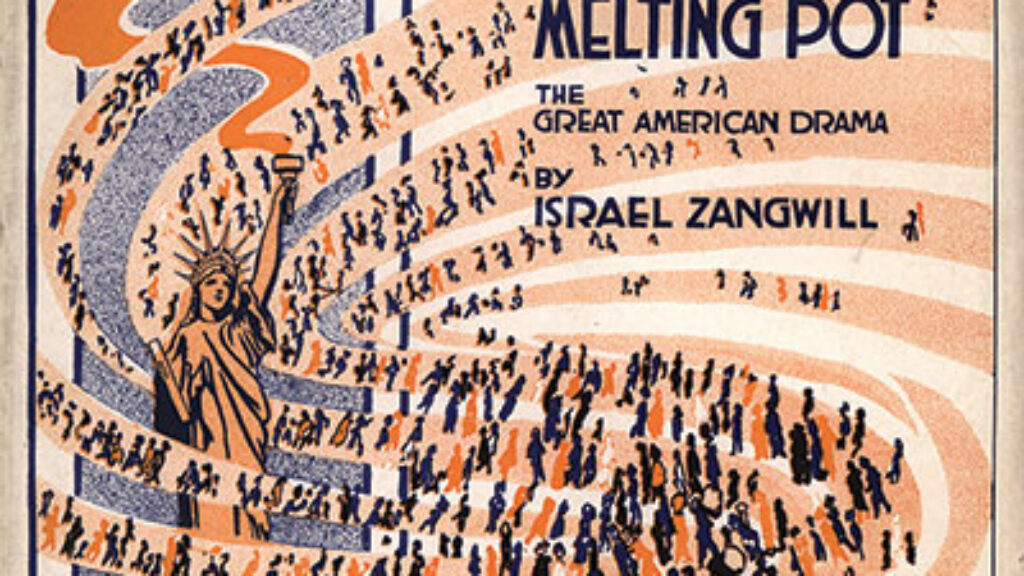

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

Between New York and Jerusalem

For twenty-five years, Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt, two of the most gifted, influential, and opinionated Jewish intellectuals of the 20th century, maintained a remarkable correspondence. Recently published, these illuminating letters provide a rare glimpse into a relationship that has too often been described as adverserial.

Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi Spies

In 1934, Hollywood's Jewish moguls met secretly at the Hillcrest Country Club to hear an unusual pitch: find Nazis in America, and stop them.

A Tale of Two Synagogues

Frank Lloyd Wright built a dazzling temple outside Philadelphia. Too bad he didn’t look closely at the synagogue of Gwoździec, Poland, built two hundred years earlier.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In