Shas: The Movie

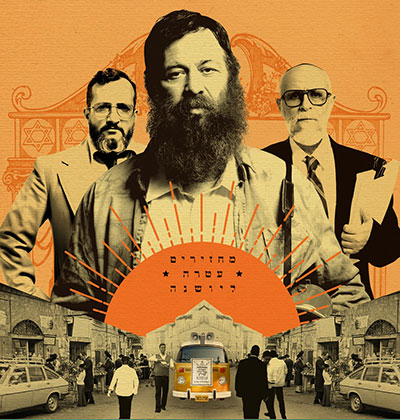

As a particularly raucous Israeli election season enters the homestretch, a recent Israeli film, now making the Jewish film festival circuit with subtitles, provides some perspective. It’s called The Unorthodox (Ha-bilti Rishmiyim, literally “Those Without Permission”) and tells the little known story of the founding of the Shas political party, a punning acronym for “Torah observant Sephardim.” Directed by Eliran Malka, creator of Shababnikim, the hip television series about ne’er-do-well yeshiva students, the film shares several similarities with the series, including an electrifying rock soundtrack that somehow works despite the cultural incongruence.

The Unorthodox is a work of fictionalized history heavily based on the testimony of a heretofore unknown Israeli printer named Yaakov Cohen, played in the film by the iconic Israeli actor turned ba’al teshuvah Shuli Rand, the star of Ushpizin. Cohen’s grassroots efforts in 1983 resulted in the founding of Shas, the very first political party to specifically represent the interests of Sephardi Jews. In 1998 Shas won a record 17 seats in the Israeli Knesset, making it a major player on the Israeli political scene. In recent years, however, the party has been weakened by criminal charges against several of its leaders, internal acrimony, and a popular perception that it operates out of self-interest more than concern for broader Israeli society. Polls for the upcoming election show it dropping to as low as six seats, not too far from the minimum threshold necessary to even serve in the Knesset altogether. The film explores what makes a political movement succeed and what can drive it into irrelevance.

Malka was working on an Israeli television miniseries about the longtime Sephardi chief rabbi Rav Ovadia Yosef when he came across an interview with Cohen. In the interview, Cohen told a story that is unknown to the vast majority of the Israeli public, including those who support, or even lead, Shas. In the film, Rand channeling Cohen narrates: “People think that politics is about the ‘big shots’ . . . but real politics, the kind that survives, comes from the bottom, from the street, from the people, from the pain.” In Cohen’s case, it was frustration that his high-school-age daughter had been kicked out of an elite Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox high school for no real reason other than being Sephardi. “Mr. Cohen,” he is chastised by her principal, “you are a guest of the haredi community, don’t abuse our hospitality.”

The rebuke echoed the condescension with which the dominant religious party, Agudath Israel, held its Sephardi voters. Cohen, along with a motley crew of neighborhood characters, patched together a political party, at first only hoping for some representation in the local Jerusalem elections, that would eventually become a major national party and a political movement. Ostensibly focused on local concerns such as funding for synagogues and houses of Torah study, what the party really provides for its constituents is a sense of pride in their Mizrahi heritage and a refusal to accept a second-class status in a European-dominated Torah culture. Cohen’s associate Yigal, a shochet with a checkered past, declares that “the [Mizrahi] Black Panthers will look like pussy cats next to us.” But truthfully, there is something gentle about the Shas revolution as depicted in the film. It’s a party of elderly Moroccan ladies from the periphery of Israel beaming as a well-spoken rabbi calls to “return the crown to her former glory.”

Cohen and Yigal share a hilarious moment in the film when they swoon over the Bee Gees’ 1977 hit “How Deep Is Your Love.” Cohen is a pious man and doesn’t normally listen to secular music, but he appreciates a good song when he hears it and is charmed by the genuine joy Yigal finds in this music. Movements fail, Malka suggests, when the party leadership stops speaking to and for its “simple people” and starts playing politics. Cohen, the most sympathetic character with the most integrity in the film, ends up getting betrayed and finds himself relegated to the sidelines of a movement he created.

Malka clearly enjoys playing with different genres as a film-maker. The visuals and music of the early part of The Unorthodox mirror a 1970s heist film, with plenty of humor and energy as Cohen’s ragtag bunch create a political party. The latter half of the film looks utterly different, like a slick, serious 1990s courtroom drama. Malka said in an interview, “The Shas party began as a beautiful dream and was the result of an incredible vision. Its crash against the harsh reality of politics was inevitable and has turned it into an establishment that is very difficult to relate to and like today.”

The Unorthodox was the second most viewed Israeli film of 2018, and I had been eager to see it ever since watching an incensed Shuli Rand storm the halls of a Bais Yaakov school in the film trailer. I finally got the opportunity at the New York Sephardic Jewish Film Festival where it debuted for Manhattan audiences. Malka was in town to speak about the film and answer some questions from the audience. As anyone who has ever attended a Jewish film festival anywhere in the country can attest, these “questions” are usually rambling statements, without a question mark in sight. This audience was predictably perturbed by the injustices the film depicts, from Sephardi marginalization in elite Ashkenazi religious culture to Cohen’s own banishment from the political home he had created. They also wanted to guess which characters correspond to real-life Shas politicians like Eliyahu Yishai and the infamous Aryeh Deri. Malka was game, but the quieter contribution of the film, an exploration of what it means for an organic community to become an organized political movement, replete with bureaucracy, egos, and corruption, was mostly lost.

Toward the end of the film, Yaakov Cohen reflects on the biblical Moses, who led the people of Israel through 40 tortuous years in the desert, only for him to be left outside once they enter the Promised Land. Cohen is comforted by imagining the pride Moses must have taken in seeing his people finally enter the Land of Israel, even if he could not participate. Cohen’s extreme humility here, echoing Moses’s own, is part of the life force that underlies any successful political movement if it is going to speak to people and channel their hopes and dreams. Reestablishing contact with this life force is one place where art and politics can meet.

Suggested Reading

The Play’s the Thing: A Revolutionary New Haggadah

The exodus from Egyptian bondage was a good thing. What about a haggadah that is "unbound"

Jake in the Box

The patriarch Jacob was the father of twelve tribes and (eventually) fêted by Pharaoh. But, as Yair Zakovitch shows, the Bible does not portray a happy man.

Is Beauty Power?

With charm, business savvy, and determination Kracow-born Rubinstein transformed herself from Chaja to Helena to “Madame.”

Jewish Geography

The Jewish peddler, the “slave of the basket or the pack; then the lackey of the horse,” did not have an easy time of it.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In