Your Time Is Up: Jabotinsky at the Sixth Zionist Congress

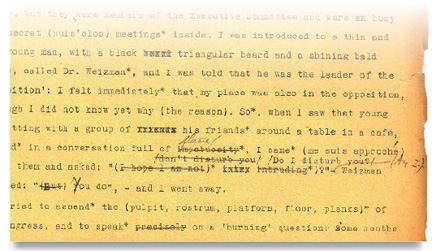

Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote his Story of My Life in Hebrew and published it in Tel Aviv in 1936. A Russian version has long been available, but it has never before appeared in English. Our rendition of the following excerpt is based on the rough draft of an English translation of the original Hebrew or Yiddish or Russian (we just don’t know). Professor Leonid Katsis discovered the rough draft almost by accident in 2010 in the archives of the Jabotinsky Institute in Tel Aviv. At the time, he was looking for proof that Jabotinsky had in fact participated in the publication of Osvobozhdenie (Liberation), the journal of the Russian Social Democrats in the early years of the 20th century. The newly rediscovered draft, annotated and corrected by Jabotinsky himself, confirms that he did.

Unfortunately, there is no indication of when the translation was undertaken, who was responsible for it, or whether there were ever any plans to publish it. Given Jabotinsky’s own direct involvement in its preparation, however, it is obviously the best available foundation for an English version of Story of My Life. We wish to express our gratitude to Ze’ev Jabotinsky for giving us the opportunity to make his grandfather’s autobiography available in this way, and for the first time, to English-speaking readers.

To what degree Jabotinsky told a true life story is hard to determine. In his Zionism and the Fin de Siècle: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism from Nordau to Jabotinsky, Professor Michael Stanislawski has characterized it as “a brilliant, but highly fictionalized, self-fashioning.” But Hillel Halkin, in his recent biography of Jabotinsky, described his memoirs more sympathetically as “a sincere if artful attempt to describe times and episodes in his life as he recalled them.”

Jabotinsky’s narrative begins with a colorful account of his upbringing in Odessa and his education in Italy. While he portrays himself as having been a Zionist practically from birth, his evolution into a Jewish nationalist was probably more gradual than his autobiography indicates. He was certainly a Zionist by the time he attended the Sixth Zionist Congress as the representative of a group of Odessa businessmen.

The congress took place in August 1903, when memories of the murderous pogrom in Kishinev were still fresh. The need to provide a refuge for the Russian Jews threatened by more such pogroms was very much on Theodor Herzl’s mind when he famously called on the delegates to authorize an investigation of the territory that the British government was prepared to offer the Zionists in East Africa. Jabotinsky, who had seen the devastation in Kishinev himself and participated in relief efforts, did not share Herzl’s sense of urgency. Jabotinsky seems to have defended Herzl against some of his more moralistic critics, but he joined other Russian Zionists in opposing the Uganda proposal. Historians disagree about the accuracy of Jabotinsky’s account of his experience at the congress, but no one doubts that it grants insight into the mind of the leader who published it in 1936, at a time when he had abandoned the organization that Herzl had founded but still sought to lead the Zionist movement.

A very amusing comedy could be written about my adventures at the congress. First of all, I was not entitled to participate in it, as I was almost a year and a half too young with respect to the legal age for a delegate, and I do not remember who the friendly false witnesses were who attested to my being twenty-four years old; my face was that of a boy, and the official in charge of the delegates’ cards did not want to accept me until I brought the witnesses. After that I loitered by myself in the corridors of the casino; I did not know anybody except those bigwigs I had seen in Kishinev, but they were members of the executive committee and were busy with secret meetings inside. I was introduced to a thin and tall young man—with a black triangular beard and a shining bald head—called Dr. Weizmann, and I was told that he was the leader of the opposition: I felt immediately that my place was also in the opposition, although I did not know yet why. So when I saw that young man sitting with a group of his friends around a table in a café, engaged in a conversation full of intensity, I came toward them and asked, “I hope I am not intruding?” Weizmann answered: “You are”—and I went away.

I tried to ascend the podium of the congress and to speak precisely on a burning question: Some months before that, Herzl had gone to Russia and talked with the minister of the interior, Plehve; the same Plehve whom we considered the instigator of the Kishinev pogrom. A passionate discussion broke out among the Zionist circles in Russia—whether it is admissible or forbidden to conduct negotiations with a monster such as him. True, both sides had agreed not to touch on this dangerous subject from the tribune of the congress, and I also knew it. Nevertheless, I decided that the interdiction did not apply to me because my experience—the experience of a journalist in Russia, skilled in the art of writing on a risky question without irritating the censor—would help me on this occasion, too, to steer clear of the reefs.

My turn came when the time allotted to the speakers had already been limited to fifteen minutes, but I was not allowed even that quarter of an hour for my eloquence. I began to demonstrate that the two issues of ethics and tactics ought not to be confused. The delegates in the corner of the opposition sensed immediately what was in the mind of that young man, unknown to everybody, with a black head of hair, speaking a polished Russian as if he were reciting a poem at a gymnasium examination, and began to stir and to shout: “Enough! No more!” Panic broke out in the hall. Herzl himself, who was busy in the adjoining room, heard the noise, came out hurriedly to the tribune, and asked of one of the delegates, “What is it, what does he say?” It so happened that delegate was the same Dr. Weizmann, and he replied briefly and emphatically: “Quatsch” (“Nonsense”). At that, Herzl came toward me from behind the podium and said: “Ihre Zeit ist um” (“Your time is up”), and these were the first words and the last I ever had the privilege to hear from him. Dr. Friedman, one of the close associates of the leader, emphasized these words with the outrageous bluntness of his native Prussian: “Gehen Sie herunter, sonst werden Sie heruntergeschleppt” (“Come down or else you will be hauled down”). I came down without finishing the defense unwanted by the man in whose defense I had taken the floor.

I realized that my task in that congress was to keep silent and to observe, and that is what I did. I found a lot of things to observe there. The Sixth Congress, the last in Herzl’s life, was perhaps the first congress of adult Zionism. The name of that examination of maturity is known as Uganda. I was one of the minority that voted against Uganda and, together with the rest of the “Neinsagers” [“the no sayers”], walked out of the hall. I wondered myself at the motive hidden deep within my soul that prompted me to vote against, in spite of what I had told my electors. I had no romantic love for Eretz Yisrael then—I am not sure that I have it now—nor could I have known whether there was a danger of a split in the movement. I did not know my people, I saw my delegates for the first time, and I did not yet have time to approach any of them; and the great majority of them, among these many who, like myself, came from Russia, raised their hand to vote “for.” Nobody tried to persuade me to vote as I did. Herzl made a colossal impression on me—this word is no exaggeration, no other description would fit: colossal—I am not one of those who will easily bow to a personality. In general I do not remember, out of all the experiences I have had in my life, one man who made any impression on me whatsoever either before Herzl or after him. I felt that truly there stands before me a man of destiny, a prophet and leader by the grace of God, deserving to be followed even through error and confusion. And even today it seems to me that I hear his voice ringing in my ears, as he swore to all of us, “Im eshkachekh Yerushalayim. . . .” [“If I forget thee, o Jerusalem”]. I believe his oath; everyone believed. Yet still I voted against him, but I do not know why: “just so”—that same “because” that is stronger than a thousand reasons.

It is a strange thing: I felt that, after that vote, the congress reached such a height that the level at which it began simply could not be compared to it. In spite of the split, the tears, and the indignation, some deeper inner cohesion between the “Neinsager” and the “Jasager” [“the yes sayers”] came about. Perhaps they learned to have more respect for one another or for the movement than they had before; and it seems to me the movement as a whole also attained greater elevation on that day, when the delegates of the people mourned their first political victory. I am sure that Chamberlain, the author of the Uganda proposal, and Balfour and many more statesmen in England and in other countries, only on that day realized what Zionism meant, and that the same is true also of many veterans of the movement.

Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Story of My Life, edited by Brian Horowitz and Leonid Katsis will be published in December 2015 by Wayne State University Press.

Suggested Reading

Patriotism and Its Discontents

While many Jews embraced the Russian revolutionary cause from the very beginning—four of the seven members of the first Bolshevik Politburo were Jews—the revolution did not embrace them for long.

EUGENE NADELMAN: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse

"Our tale's debut / Takes place in 1982 / When I, for one, if not exactly / A double of our leading guy / Was like him, bookish, awkward, shy." - Coming of age in iambic tetrameter.

Lost in Translation

When Aviya Kushner encountered the Bible not in Hebrew, but in translation, she was shocked at how different it was, both in form and in substance.

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In