A Mechitza, the Mufti, and the Beginnings of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

In one of the more chilling testimonies cited in Hillel Cohen’s account of the 1929 riots in Palestine, an elderly Jewish survivor recalls how his mother had tried to shelter him when he was five years old from a rampaging Arab mob in what looked like the safety of a friend’s home in Safed. But then:

The Arabs threw hundreds of stones at the house, at the windows and shutters. They beat on the doors and shutters with huge clubs and cast blazing torches through the windows. The house began to burn. The shutters, curtains, and even my mother’s and sister’s nightgowns began to go up in flames.

The teller of this tale, Yisrael Tal, narrowly escaped the siege (together with the other members of his family) and grew up to become first a British soldier and then a very distinguished Israeli general. He was also, as Cohen points out, “the father of the Merkava tank.”

“Talik” was by no means the only leading figure in the Israeli Army who had such a boyhood experience, or a worse one, in August of 1929. The future general Rehavam (“Ghandi”) Ze’evi, living in Jerusalem, saw his first corpse that year, one of the victims of an attack in Bayit VeGan. And Cohen relates in detail the story of Mordechai Maklef, the IDF’s third chief of staff, whose parents and siblings were brutally murdered by Arabs in Motza, and who himself was rescued from a similar death only at the last minute—perhaps by an elderly rabbi who was soon slaughtered himself, and perhaps by an Arab whose piety prevented him from killing small children, and perhaps by both. We have, as Cohen tells us, two different and not necessarily mutually exclusive accounts of what happened.

In another book, these episodes might have served as unsettling reminders that the Jews were once at the mercy of anti-Semitic mobs not only in the diaspora but in the Land of Israel itself. They might have supplied evidence of the necessity of a Jewish state as well as an explanation of the emergence of Palestinian-born men capable of leading the struggle to establish and preserve it. In Hillel Cohen’s account, however, they represent the deplorable but inevitable consequences of the intrusion of the Zionist movement into an area where it was unwelcome and where it had no clear right to be: “As the Arabs saw it, in the summer of 1929 they killed not their Jewish neighbors, but rather enemies who were seeking to conquer their land.”

Cohen’s analysis of the situation in 1929 goes very much against the grain of the usual Zionist narrative and even the non-partisan historical research concerning this period. There, the emphasis is usually on the way in which the riots at the very end of the 1920s constituted a rather abrupt departure from the peaceful conditions that had prevailed in Palestine since 1921. They came at a time when the Zionist enclave in Palestine was enmeshed in economic crisis, when Jewish emigration from Palestine exceeded immigration, and when the Zionist project, as the historian Bernard Wasserstein put it in his The British in Palestine: The Mandatory Government and Arab-Jewish Conflict, 1917–1929, looked like “a sinking ship.”

Nobody contends, of course, that the riots were bolts from the blue. Most historians trace them back to a dispute over a mechitza, of all things, that began on Yom Kippur in 1928, when British constables forcibly removed a makeshift partition between male and female worshippers. What the Jews were and weren’t allowed to do in the then-narrow space adjacent to the Muslim-owned Western Wall wasn’t quite clear, and disagreements had led to altercations between Jews and Arabs in the past, but only in 1928 did the problem mushroom into a lengthy and eventually bloody struggle. Both Jews and Arabs ramped up their rhetoric and engaged in provocative actions but “there can be little doubt,” according to Wasserstein, “that the key to what occurred in Palestine in 1929 was the . . . year-long campaign” on the part of the Muslim leader Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, “rousing the Arabs of Palestine to stand against the alleged threat to the Muslim holy places in Jerusalem,” alleging, for instance, that the Yom Kippur mechitza was proof of a Zionist plot to take over the Temple Mount. Wasserstein provides a detailed overview of what he labels the mufti’s “vast campaign of propaganda and action” and the incensed and bitter Jewish reaction to it before describing the intercommunal violence that ultimately ensued in August of 1929, resulting in the death of hundreds of Jews and Arabs.

In Cohen’s revisionist narrative there is no hint that the Zionist movement in the late 1920s was a sinking or even a foundering ship. There is no mention of anything that might have induced the Arabs of Palestine to doubt that the Jews would have the power to take control of their land. And there is less discussion of the mufti and his “year-long campaign” than there ought to be. Between his Introduction and the main body of his text Cohen has placed a “Chronological Overview of the Events,” commencing with Yom Kippur 1928 and concluding with the return of a few members of the devastated Jewish community of Hebron to the city in May 1931. This list, he notes, “includes events that are not discussed in the book.” One of these events is an “Islamic conference chaired by Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Hajj Amin al-Hussayni and attended by clerics from throughout the Muslim world” that “demands restrictions on Jewish activity at the Western Wall.”

Cohen never quotes the speeches of the mufti or any of his acolytes at length, and he allows us only fleeting, indirect glimpses of the vast campaign Wasserstein described, through brief quotations from the work of other scholars and, in one case, an eyewitness. He briefly refers to Rana Barakat’s description in her 2007 University of Chicago PhD dissertation of the way in which the mufti “fanned the flames in the conflict over al-Buraq” (the Muslim name for the Western Wall, where Muhammad’s steed, al-Buraq, was legendarily tethered). Cohen also quotes Eitan Wijler’s 2005 University of Haifa master’s thesis in which he asserts that al-Husseini’s efforts to export the conflict from Jerusalem and his policies in general (like those of the Zionist Revisionists) “led to growing extremism and the deterioration of the situation” in the months leading up to the riots. And he describes how an eyewitness (at the age of five) to the events in Safed in 1929 recalled (at the age of 80) the Arab crowd being stirred by the call “Seif al-din Hajj Amin [Hajj Amin (al-Hussayni) is the sword of the faith].” But this does not give the reader anything like a full picture of the mufti’s conduct during the year to which Cohen’s book is devoted.

Another item appearing in Cohen’s chronological overview is a Hebrew newspaper’s interview with the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Palestine, Abraham Isaac Kook, on August 15, 1929. As Cohen puts it, Rabbi Kook called at this time, just before the riots, “for the evacuation of the Maghrebi quarter, the Arab neighborhood adjacent to the Western Wall.” Rav Kook’s passionate and combative statement is discussed and quoted extensively in the main text of Year Zero, as is his expression of regret three months later for, in Cohen’s words, “his involvement in fanning the flames of the Western Wall controversy.” But what Cohen refrains from making entirely clear is to what, exactly, Kook was responding.

Cohen clearly wishes to undermine the Jews’ longstanding conviction that they were the victims in 1929. Rejecting the common attribution of the anti-Jewish riots of that year to the Palestinian Arabs’ shocking penchant for violence, he attempts to provide an unbiased view of the situation that produced them. At bottom, he insists, despite their deplorable excesses, the Palestinians who murdered more than a hundred Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and elsewhere were manifesting their understandable frustration with the Zionists’ attempt to usurp their homeland—even when they were massacring non-Zionist Jews from the Old Yishuv. For the Zionist movement had created a situation in which “all Jews now looked the same to them.”

Cohen does indeed convey to his readers the sense of outrage felt by many Palestinian Arabs at the privileges accorded to the Zionists by the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate. He makes a reasonably strong case that, from the Arab point of view, there was a consensus among Jews that Palestine belonged to them and that this was:

the major ideological factor that motivated the attackers and murderers, their justification for indiscriminate attacks on Jewish settlements and communities, no matter what their political and religious affiliations.

Cohen notes that some of the ultra-Orthodox victims of the riots of 1929, in Hebron for instance, had substantial ties to the Zionist movement, links that were strong enough for their assailants to conclude that the lines separating Zionist and haredi were fuzzy. Where Cohen does not succeed, however—in part because of his tendentious omissions—is in convincing the reader that the riots of 1929 were the outcome of the collision of two inevitably opposed forces rather than primarily the result of the machinations of a religious demagogue.

Cohen follows up his chronology of the events of 1929 with an enumeration of the “Casualties in the 1929 Riots.” It shows that the numbers of Jews and Arabs killed and wounded were roughly equal, but also includes a note that clarifies the very different ways in which the Jews and the Arabs met their deaths:

A large majority of the Jews slain were unarmed and were murdered in their homes by Arabs. Most of the Arab dead were killed as they attacked Jewish settlements or neighborhoods. Most of the Arabs were felled by bullets fired by the British armed forces; some were shot by members of the Haganah. As will be shown, about twenty of the Arabs killed were not involved in attacks on Jews. They were killed in lynchings and revenge attacks carried out by Jews, or by indiscriminate British gunfire.

It would have been helpful if Cohen had broken down these numbers a little further and told us how many Arabs were unjustifiably killed by Jews, but if my count is correct, the number is fewer than 10, and of these five were the victims of a revenge attack by a single enraged Jewish policeman, Simha Hinkis, in Abu Kabir, near Tel Aviv. Cohen gives Hinkis an extraordinary amount of attention. Indeed, no other Jew—or Arab or Englishman, for that matter—has an entry in the index to Year Zero that comes close to being as long as the one devoted to him.

Cohen’s penchant for highlighting the Jews’ major—if shared—culpability for what took place in 1929 raises questions about his underlying convictions, questions that are not improper to raise with respect to the author of a book like his. For as Cohen himself observes, “it is impossible to address the events of 1929 without addressing moral issues,” including, above all, the following question: “did the Zionist aspiration of founding a Jewish state that could cure the Jews of the malady of living as a humbled minority justify injury to the Arab inhabitants of Palestine?” But this, Cohen goes on to say, leads ineluctably to another question: “did the Arabs have a right to oppose Zionist settlement?” And if so, how far could they legitimately go?

Cohen tosses these questions around in the main body of his text, but he offers an answer of his own only in the book’s Afterword:

[T]he Jews, as a persecuted people whose property and lives were in constant danger, had a right to take refuge in the Land of Israel. But this right did not strip the Arabs of their own rights in Palestine, nor can it justify every action and policy pursued by the Zionist movement to achieve its larger goal.

But what about that larger goal itself, the establishment of a Jewish state? Was that justified? Cohen doesn’t say yes and he doesn’t say no. He is under no obligation to do so, of course, in a historical study. But his evasiveness with respect to the question that he himself has posed justifies Benny Morris’s description of his stance, in a review in the Israeli online journal Mida of the original Hebrew edition of this work, as “nebulous post-Zionism,” if not his further deduction that Cohen apparently wishes to deny the legitimacy of a Jewish state altogether. And it should put supporters of the Jewish state on guard against the distortions that even an author who strives to rise above nationalist bias can introduce into his historical narrative.

Suggested Reading

Lamed-Vovnik

André Schwarz-Bart's posthumous The Morning Star goes where no Holocaust novel has gone before.

Water Shall Flow from Jerusalem

In Israel even well-to-do families can be seen scooping bath water out of the tub to water backyard plants and hygiene classes teach students to use the least amount of water when showering and brushing their teeth. Israel's way with water may be the way out chronic water shortages.

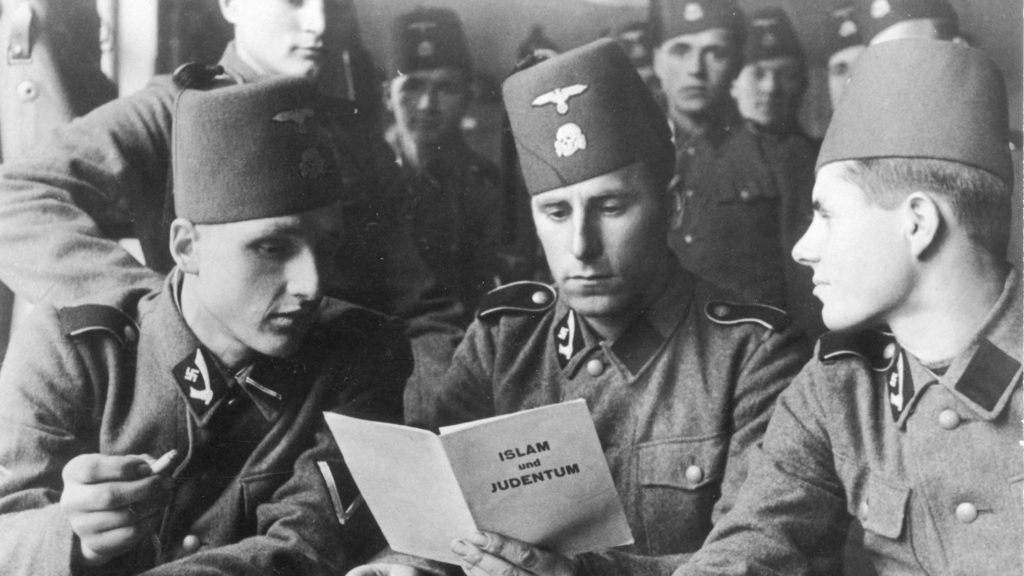

The Hands of Others

Many people know of Mufti al-Husseini's SS activities. But how many Arabs shared his admiration for Hitler and attraction to Nazism?

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In