A Fraternal Note

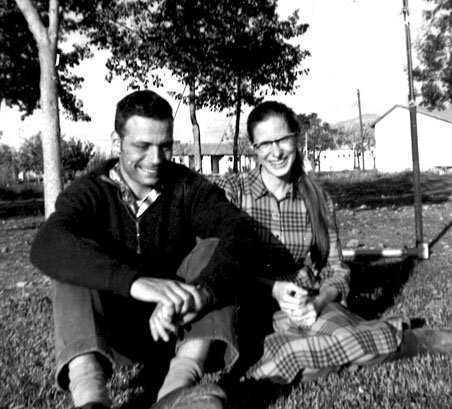

When my brother and his wife arrived in Haifa on Rosh Hashanah 1959, they were in their early twenties. First off they changed their names. In honor of our father Joseph, my brother, born as Robert Eliot Reiss (his middle name given him because of a poet he grew to loathe, T. S. Eliot), switched to Reuven Ben-Yosef. According to his widow Jody, now Yehudit—still very much alive in Jerusalem—their first year on a kibbutz was “rather quiet” because he insisted they speak only Hebrew.

Now that some of his work has been posthumously published in English, I can atone for my lack of Hebrew by poring over the poems in Michael Weingrad’s recent translation. I can read how on Israeli army patrols my brother cleared mines near the Sea of Galilee—or else on duty in Gaza how he filed past roadblocks, “unknown alleys, peepholes.” I can read his steamy poems about my sister-in-law. I can even read about myself. These poems are the best way for me to hear my big brother’s voice again.

With a single slim volume of poems in English published shortly after he left the United States, Ben-Yosef began a 40-year hardscrabble career as a writer, translator, and public school teacher eventually based in Jerusalem. He and his family flew overseas to visit us a few times but otherwise hunkered in Israel. Despite his testy entreaties, neither our parents nor our younger sister joined him and his growing family abroad. My sister, Lucinda Luvaas, became an acclaimed visual artist on the West Coast. My secular Jewish parents, grieved by his absence and tempted to emigrate to be near him, decided to remain in the cosmetics business in New York. I moved to Ohio, where I taught creative writing as—what else?—a poet!

What was it like growing up with a brother who was also a poet? Four years older than me, he was my role model, though he almost never gave me the approbation I craved. When Mom and Dad made a fuss over his poems, I began to turn out my own verse for all occasions: birthdays, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas—in those days we decorated our annual Christmas trees with cherished ornaments. I got hooked on my brother’s early poems; I can still recite his opening lines about a budding pre-teen girl:

Soon the angles and jutting fragments

Will blend into ovals

Of pink and whiteness.

One reason my brother left this country might have had to do with his being badly beaten up as an 11-year-old by an anti-Semitic street gang. I remember driving through northern Manhattan with a private detective—he showed me his gun—trying to find the culprits. We never found them, just as my brother never found himself at home in Christendom. He disdained our parents’ infatuation with Unitarianism and considered becoming a Roman Catholic. He’d dropped out of college, enlisted in the American army, become an Army Language School–trained translator of Russian, and was stationed—of all places—in Germany. Once he was discharged from the service and found Judaism, he denounced the United States with its vast wealth and power. Years later, in his second “Letter to America,” he laced into our sister for being a “captive among the gentiles.”

Weingrad’s Letters to America: Selected Poems of Reuven Ben-Yosef has as its centerpiece the title poem, a sequence of 13 such epistles written between 1974 and 1977, that addresses Reuven’s family back in the United States in tones that are full of longing as well as anger. His first poem in the sequence, “Letter to My Brother,” reaches out to me:

We share no language, and yet perhaps

some brotherly bond exists that strives, across

the mighty waters, to touch

In his introduction, “Reuven Ben-Yosef and the Family Reiss,” Weingrad contends that Ben-Yosef’s on-again, off-again yearning and rage for the American branch of his family played a big part in the literary achievement of his Letters. The emotional intensity crackling in his missives to our mother and sister, as well as to our father, and even to our childless sister’s non-existent progeny, comes together with his use of iambic pentameter—not common in Hebrew poetry. The result is an echo chamber of cris de coeur couched in stately lines of verse.

By then my fiction-writing brother-in-law, Bill Luvaas, and I had written the equivalent of our own epistles to our abrasive sibling. Bill’s debut novel and my first book of poems found bittersweet ways of writing about brother Reuven. Without being able to read what Reuven was saying, we relied on memories of him and wrote books that unknowingly answered his eventual verse letters.

Families harbor feuds the way governments hold onto foreign policy: Nothing changes for eons until, with some luck, there’s a breakthrough. Years later when I flew to Israel and gave Reuven my second book, I was afraid that he would read my poem “Brothers,” get mad as hell, and never speak to me again. Instead, he grinned at my lines: “So where are you now, Mr. Top / Dog on the Bunk Bed, Mr. Big / Back on the High School Football Team?” He told me he was glad I still remembered that he lettered in football!

I’m glad I still remember him playing our family’s baby grand; one of his own Copland-like tunes has haunted me for more than 60 years. I’m glad I remember our dinnertime game: I would brag that I owned all the railroads east of the Mississippi, while he said he owned every train west of Chicago, including the Burlington Zephyr and the Super Chief. I’m glad I don’t remember him, when I was an infant, whacking me over the head—so my mother told me—with a toy metal pistol.

Now that I can finally read his poems, I see how, even though we weren’t personally close, our work developed in parallel—or what Saul Bellow called axial—lines over the decades. His long poem about New York, “The City,” complements my own Big Apple poems; his portrait of the poet as an “aging lion” echoes my portrait of the king of beasts in “Three Leos”; his description of our father’s funeral service aboard a rented boat pairs well with my elegy for our dad in my first book; his frequent preference for stanzas with the same number of lines equals my own; his experiments with visual poems match “concrete” verse I continue to tweak; his love of imagery and sound shows (at least in translation) in seven stark words I wish I had written: “A shack in a stand of pines.”

Unlike such colloquial late 20th–century Israeli poetry as Yehuda Amichai’s, and unlike much of my own work, which has been called “plainspoken,” Ben-Yosef’s verse apparently deploys biblical and demotic Hebrew in dense, allusive ways. If the British poets Milton and Wordsworth represent opposite extremes of style, my brother is closer to Milton than to the author of The Prelude. The issue of Ben-Yosef’s strenuous—“literary”—use of language seems to have compounded the difficulties of translating his work. To sit down and read my brother’s poetry is, even in English, not an experience of free-flowing transparent lines of verse.

Here is one poem my brother wrote in 1993 that works perfectly in translation. I can only imagine it in Hebrew:

“In the Shade of a Tree”

“No!” cried the woman and beat the air

that passed like a whisper over the open grave. “If,”

said the young man with the orders in his hand, still

stunned by the news. “Undoubtedly,” explained

the government spokesman, pointing to the maps.

“Nonsense,” pronounced the old man sitting in the park

in the shade of a tree, millions of leaves rising

to the sky.

Thanks to Weingrad’s introduction, I learned that Ben-Yosef was so taken with my first book, The Breathers, that it actually inspired him to write the “Letters to America” sequence. Zionist though he was, his selected poems refer to New York, not always derisively, at least as frequently as Jerusalem—and he describes at least as many settings in the United States as in Israel. He may have thought he was entering the future, but like many another voyager he ended up being borne back ceaselessly into the past.

What irony for a poet with such a grudge against America to be published here! Fifteen years after he died, a major reassessment of Reuven Ben-Yosef’s work may win him readers—an audience—on these shores. As far as I’m concerned, this book is a triumph for our family.

Letter to My Brother

I write to you with simple words,

because you do not understand Hebrew.

We share no language, and yet perhaps

some brotherly bond exists that strives, across

the mighty waters, to touch, so that

one of these days, in one of these lands,

you’ll see that you have not yet reached your self.

I write to you because you do not understand,

and yet you want to be my brother,

not like those wandering relatives that every Jew

has somewhere else in the world, but my own flesh

and blood, your lack of self resounding

in my very bones, and didn’t you once say,

“From this sad distance I’m proud of you.”

I write to you because you do not want to be,

my brother. The king’s image has left you, and nothing

remains but a clean hand on a glass stem,

wine by the sea, a holiday, your eyes gazing east

with longing, your mouth swallowing, your heart

aching, softly beating, how pleasant it is

to think of one’s blessings, to relax in reverie.

How good it is—hinei mah tov—to bear your pain

inside you, dry all the while, with salt and wine

in your eyes, and the horizon revolving like a gear

from evening to morning and back again. Come back again,

my brother, stop yearning and read what is written.

These simple words I write to you, your brother

who lives on the Street of the Watchman, in Israel.

—Reuven Ben-Yosef

From Letters to America: Selected Poems of Reuven Ben-Yosef, edited and translated by Michael Weingrad (Syracuse University Press, 2015). Reprinted with permission.

Brothers

Eighteen years you beat me over the head

with the butt end of our brotherhood.

So where are you now, Mr. Top

Dog on the Bunk Bed, Mr. Big

Back on the High School Football Team?

You hauled ass out of that town

with its flimsy goalposts.

Now you’re down there with your Dead

Sea, your Jerusalem, busy

with the same old border disputes

that sparked our earliest fist fights.

Israel is just another locked toy

closet on your side of the bedroom, split

by electric train tracks. It’s as if

you never left home at all: Yesterday

in a bar in Washington Heights

I saw a man who could have been you.

The Jets were playing the Steelers with two

downs to go, and in the icy

lightshow of smoke

he lifted a pitcher of beer

and swilled it just as the screen

blazed red with an ad for Gillette.

And I thought, Here is my blood brother

whose only gifts to me were kicks

in the teeth, his cast-off comic books,

and worst of all, wrapped, sharpened

for a lifetime,

the perfect razor of my rage.

—James Reiss

Suggested Reading

The Sephardic Mystique

In the late 18th century, an ardor for ancient Greek art and literature swept through German letters. German Jews were not immune, yet during the same period, they also devoted themselves to recovering the linguistic, artistic, and literary heritage of medieval Sephardic Jewry.

Pop Toys and Power Politics: Israel and the Eurovision Song Contest

Eurovision is Israel's chance to shine on the world stage for something other than the Palestinian conflict, but Hamas and PIJ found the song contest an all-too-tempting target.

In Whose Image?

On the spectrum between animal and divine, where do human beings fall?

As Though the Power of Speech Were an Ordinary Matter

Moods provides glimpses into Yoel Hoffmann’s life in literature and his ambivalence about the project of capturing life in words.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In