The Sephardic Mystique

In the late 18th century, an ardor for ancient Greek art and literature swept through German letters. From Winckelmann’s history of ancient art to Goethe’s adaptation of Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris, Greece exercised a kind of tyranny over Germany, to use Eliza Marian Butler’s famous phrase. As eager consumers of German culture, 19th-century German Jews were caught up in this fascination, notwithstanding the anti-Semitism that sometimes lay behind efforts to elevate Germany’s alleged Hellenic inheritance above its Hebraic one. Yet, during the same period, German Jews also devoted themselves to recovering the linguistic, artistic, and literary heritage of medieval Sephardic Jewry. Indeed, the Sephardic mystique may have been even more central to German Jewish identity than Grecophilia was to German identity.

The history of this cultural obsession is the subject of German Jewry and the Allure of the Sephardic, a new book by John M. Efron, one of the leading historians of modern German Jewry. As he notes, Efron is hardly the first to take note of the “Sephardism” of 19th-century German Jewish culture. Ismar Schorsch’s groundbreaking 1989 essay “The Myth of Sephardic Supremacy” surveyed its expression in everything from synagogue architecture, to literature, to scholarship, and many other scholars have followed. Efron, however, has written the most sweeping, detailed, and discerning account of this phenomenon to date. His signal contribution lies not simply in the wealth of materials he has gathered, nor even in his sensitive and acute analysis of them, but in his calm unravelling of “the entangled relationship between orientalism and the Jews,” which has been the subject of a great deal of historical misunderstanding ever since Edward Said’s famous 1978 study of imperialism and the 19th-century European fascination with the Orient.

The key to understanding the modern German Jewish love affair with medieval Sephardic culture is to see it as a result of repulsion as much as attraction. As Efron writes, the “celebration of Sephardic Jewry led simultaneously to a self-critique, often a very harsh one, of Ashkenazic culture.” With the 18th-century Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, westernizing German Jews began to feel disdain for the still largely traditional Eastern European Jewish masses. Despite sharing an Ashkenazic heritage and identity, German Jews who responded to the Enlightenment call for Jewish “civil improvement” and “regeneration” recoiled from everything about their Eastern European co-religionists, from the Yiddish they spoke, to their dress and manners, to the way that they prayed. The so-called Ostjude, or “Eastern Jew,” reminded his German brethren of a ghetto existence they were desperate to leave behind them.

In the course of running away from this shadow of their own past, German Jews found another, more usable past in medieval Sephardic Jewry. This is the origin of the image of the era of Spanish Jewish life under Islamic rule, especially from the 10th century to the 12th, as a “Golden Age” of extraordinary Jewish achievement and cultured openness to the world. Yet, the charm of Sephardic Jewry for 19th-century German Jews extended beyond giants such as Maimonides and Judah Halevi. German Jews also found the later, tragic history of Spanish Jewry absorbing, and they often felt a special kinship with the Marranos, whose dilemmas of identity they commiserated with and whose tenacious clinging to an inner sense of Jewishness they admired. Above all—and this is key to Efron’s argument—German Jews were drawn to the Sephardic Jews’ seeming embodiment of beauty, dignity, and refinement, as opposed to the ugliness they perceived in—or projected onto—Ashkenazic life.

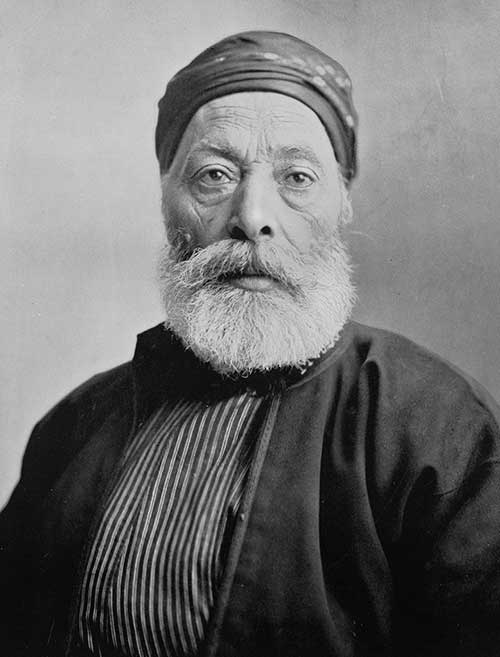

The construction of a self-consciously “Sephardic” aesthetic took many forms—visual, literary, even aural. Believing the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew to be both more correct and more euphonious than either Ashkenazic Hebrew or (even worse) Yiddish, German Jewish elites pursued a “sonic makeover of the Jews,” more than a century before Eastern European Zionists would famously do the same. Through their painting and photography, as well as in new fields such as physical anthropology, German Jews often accepted the anti-Semitic stereotype of Ashkenazic Jews as ugly while propagating a new racial myth of the “beautiful Sephardic Jew.” German Jews built synagogues in Berlin, Leipzig, Dresden, and elsewhere that resembled neo-Moorish palaces; they devoured historical novels about Marranos; and their historians, such as Heinrich Graetz, extolled both the medieval Sephardim and early Islam while tying the alleged degeneration of Ashkenazic Jewry to the persecutory climate and noxious influence of Christendom. As Efron shows, the “myth of Sephardic aesthetic superiority” made waves beyond German shores. One of the most fascinating—and troubling—examples of its circulation was the American Jewish physician and anthropologist Maurice Fishberg’s The Jews: A Study of Race and Environment (1911), which was widely regarded at the time as “the authoritative source on the anthropology and pathology of the Jewish people.” Stripped of context, the photographs and captions in Fishberg’s volume, contrasting proud, graceful Sephardic faces with Ashkenazic visages of “mongoloid” and “negroid” types, would seem right at home in the library of modern racial anti-Semitism.

Efron displays a keen sense of the ironies that characterized this new, romantic aesthetic in 19th-century Germany. At a time when European nationalists were ransacking the distant past to find links to their “ancient forebears,” German Jews were preoccupied with severing such links; “the myth of Sephardic supremacy,” Efron argues, “was an Ashkenazic invention and it was one that highlighted distance and difference from the object of their paeans and not linkage to this mythical culture.” German Jews admired and even adulated the Sephardim, but, with few exceptions, most of them fabricated, they did not claim descent from them. Also paradoxical was the relationship between German Jews’ “orientalism” in everything from their scholarship to their synagogue architecture and their simultaneous westernization and identification with German culture. Considering that opponents of Jewish emancipation typically stressed the non-native, indeed “oriental” character of the Jews, this, as Efron notes, was a “delicate balancing act.”

Efron’s knack for unmasking paradox and making distinctions is put to fine effect in his trenchant criticism of Edward Said’s now virtually canonical argument that orientalism was the handmaiden of British and French imperialism and combined (in Efron’s words) “an expression of fascination with the Muslim Near East mixed with unalloyed condescension.” While Said has often been faulted for skipping over German orientalist scholarship (and stacking the deck for his argument in the process), few have probed the Jewish dimension of German orientalism with as much depth as Efron. As he shows, “the German-Jewish Sephardicists, whether communal leaders, anthropologists, novelists, scholars of Islam or of the history of Jews in Muslim lands” approached Islam with something closer to admiration than condescension. Nearly universally, they viewed the Muslim world not as “ripe for imperial domination, but, rather, as a place from which contemporary Europe could learn lessons about tolerance and acceptance.” Jewish orientalism, in other words, was marked by an “antipathy to Christianity” and to the resistance to full civic inclusion for Jews in contemporary Europe it appeared to underlay. It was only with regard to Eastern European Judaism, which they regarded, ironically, as a perversion of a purer, more authentic “oriental” Judaism, that Jewish orientalists evinced any orientalism in Said’s sense of exoticizing disdain.

“This is a book about beauty, about style, about appearance,” Efron’s book opens. I would add that it is also a beautiful book that reveals tremendous craftsmanship. Each chapter is a finely wrought marvel of crystalline prose, careful scholarship, and often exquisite analysis. Efron knows how to turn a sentence—“The rays of Spanish Jewry’s Golden Age continued to shine long after their community’s tragic end, and it may be argued that those rays enjoyed their greatest luminosity in modern Germany”—yet his writing is never overly precious. No one can read this book without feeling their eyes opened wide to the remarkable range and complex motivations of 19th-century German Jewish Sephardism. Nevertheless, it seems to me that there is a larger argument here about the nature of Jewish modernity, one that Efron may hint at even if he holds back from boldly articulating it.

To simplify somewhat, the debate over the origins of modern Judaism has traditionally pitted scholars who underscore the decisive influence of new ideologies and ideas against those who stress migration and the transformation of Jewish behavior. The former regard the rise and spread of Jewish modernity largely as an intellectual revolution; the latter see it as a social revolution. Efron introduces the possibility of viewing Jewish modernity primarily as an aesthetic revolution. Becoming modern, in this view, was above all about cultivating a particular look, sound, and affect. There was, of course, a cognitive element to this, but it was less conceptual than emotional, and the changes in everyday Jewish practice were closely bound up with the emergence of a new set of affinities and aversions. The aesthetic revolution, in short, may be where the intellectual and the social axes of change converge.

Efron limits his analysis to the German Jewish experience, but his emphasis on aesthetics could be applied more broadly. For even in places where Jewish modernization clearly did not depend on an embrace of liberal and secular values, but was chiefly a function of non-ideological acculturation, it was always marked by the appearance of new modes of feeling and self-fashioning. That is true whether we are talking about Germany or England or the Ottoman Empire.

In the end, German Jewry’s fascination with the Sephardic is an almost closed chapter of history. Vestiges endure, perhaps most notably in the continued representation of Muslim Spain as a “Golden Age” for Jews, but also in the surviving examples of the neo-Moorish style in synagogue architecture (though most of the German sample cases Efron discusses were destroyed). But as Efron himself acknowledges in his all-too-brief epilogue, in the early 20th century, German Jewish Sephardism was effectively supplanted by a new avant-garde Jewish aesthetic, one that idealized the very East European Judaism its precursor had repudiated.

Today, when Eastern Europe is more distinguished by Jewish absence than presence, traces of this “second aesthetic revolution” can still be found, whether in the popularity of klezmer bands, or the neo-Hasidism inspired by Shlomo Carlebach and Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, or in the appeal of what Jeffrey Shandler and Cecile Kuznitz have called “postvernacular” Yiddish. We now stand at a distant remove not only from medieval Sephardic culture, but from the modern German cult of the medieval Sephardim that, as John Efron shows in this extraordinary book, once had such deep and widespread resonance.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love

The late Michael Wyschogrod may have been the boldest Jewish theologian of the 20th century.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Stepan Bandera: A Rejoinder to Dovid Katz

Konstanty Gebert responds to Dovid Katz's critique.

Jews in Trench Coats

From mortal risks to the mundane office politics and antisemitic prejudice, Douglas London’s memoir of working for the CIA reveals the inner workings of America’s most secretive agency.

The Birthright Challenge

Eleven years and four books on, can Birthright Israel save diaspora Judaism?

drpaaz

Interesting book review. As a Jew of Sephardic descent I am particularly curious about the subject and look forward to reading it.