Letters, Summer 2016

Existential Presences and Slippery Slopes

Leora Batnitzky’s feature essay on Michael Wyschogrod (“Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love,” Spring 2016) is on the whole as engaging as it is illumining. One might question, however, whether it makes sense to associate Heidegger’s notion of Dasein with the move of Buber and Wyschogrod to “prioritize existential presence, or being-there (Dasein), over ontological essence (Sein).” Heidegger is most famous for identifying human being as Dasein, hardly the meaning Buber and Rosenzweig could have had in mind when they translated as “Ich werde dasein” the Hebrew “eheye” in Exodus 3:14. Moreover, the passage quoted leaves one with the impression (quite mistaken) that one could associate Heidegger’s ontological notion of Sein with “essence,” Wesen, in any traditional sense. Further, human being-there for Heidegger is marked, in the first instance, by an existential “thrownness” (Geworfenheit), as being “thrown” into its “there.” How could one square such an idea with the God who speaks to Moses from the burning bush? One might add that the thrownness that fundamentally distinguishes Heideggerian Dasein hardly applies to Moses, who out of intellectual curiosity freely approaches the burning bush and who is first addressed by God on account of that free initiative (Ex. 3:4). We perhaps more aptly cast as “Hiersein” the existential presence that characterizes the Moses of the initial speech-act (“hineini”) in response to the divine call.

Phillip Stambovsky

New Haven, Connecticut

Heartfelt thanks to Leora Batnitzky for her considered, thoughtful, and instructive tribute to Michael Wyschogrod as Jewish theologian. Her essay illuminates the problematic of Wyschogrod as an important starting place for ongoing reflection.

I agree that Wyschogrod’s God is more biblical than rabbinic and that his stress of God’s favoritism with regard to Jews is a provocative way of presenting divine love as personal. But I don’t agree that Wyschogrod struck that posture as a literary “provocation.” He genuinely thought and held that being Jewish is what you are, not what you believe or do. Circumcision is, for the one undergoing it, not a deed or a belief. It’s a mark in the flesh that precedes choice. Wyschogrod thought that, when God set aside a people for His purposes, He didn’t want to take the chance of letting God’s election depend on their cognitions. It was in that spirit that Wyschogrod wrote to Cardinal Lustiger—not urging him to abandon his Christian beliefs—only to remind him that, being Jewish by birth, the obligation of kashrut still obtained for him. In the same stubborn (if you will, eccentric) conviction, he brought it about that the body of a deceased Jew was reinterred in a Jewish cemetery. Whatever that was about, it wasn’t about style.

Professor Batnitzky construes Wyschogrod’s bypass of rabbinic mediation to mean that Wyschogrod opted for the Protestant alternative of sola scriptura. That would impute to Wyschogrod the view that God is reached exclusively through mediation by text, just a different text. Not so. When Wyschogrod deplored the “ossification” of spirituality in Jewish orthodoxy, and looked rather for the Jewish spirit to live expressively in novels and the other arts, what he looked for was divine inspiration, coming to the writer or artist direct and unmediated.

The last time I met Michael, I told him that I had some questions to ask him about theology. As we talked, I mentioned that I had come to a point in my life where I felt more able than previously to get guidance in prayer. Rather than look puzzled or incredulous, he merely said, “Then what do you need me for?” I asked him what he thought of the rabbinic view that prophecy has died out of Israel. He said they were simply recording an empirical/historical fact, not postulating a principle. Still pressing the point, I asked him whether he himself thought that God had stopped communicating with us in the present era. He smiled. “Do you mean, has God retired and moved to Florida?” He didn’t think I was asking whether the Bible had retired and moved to Florida.

Lastly, Professor Batnitzky sees a “danger” in Wyschogrod’s claim that God is present in the body of the people of the covenant. Here one must read The Body of Faith with the principle of charity. The farthest thing from Wyschogrod’s mind would have been to regard real-life Jews idolatrously. He noted the unusual reiteration, in our sacred history, of the fact that we took the Promised Land from its previous inhabitants by force of arms and that the land was bestowed conditionally. He viewed the rebirth of Israel with religious anxiety, because he saw it as conferred on the Jewish people now under the same conditional title that had held in biblical times.

The “logic” of any view can be taken as a prompt for the slide down the slippery slope to absurdity. Wyschogrod was a modest, charitable, and self-disciplined man of sober realism. He was far from taking Jews in their historical reality to be identical with the divine, in whole or in part.

Abigail L. Rosenthal

Professor of Philosophy Emerita

Brooklyn College of The City University of New York

Leora Batnitzky Responds:

It would take several volumes to elucidate the similarities and, as Phillip Stambovsky, points out, the profound differences between Heidegger, Wyschogrod, Buber, and Rosenzweig. My point was not to conflate them. Rather, in gesturing toward an affinity between Heideggerian Dasein and Wyschogrod, Buber, and Rosenzweig’s respective notions of existential presence I was pointing to some of the ways in which these three Jewish thinkers all challenge rationalist notions of God as well as of human freedom. In doing so, all three make a point of affirming biblical anthropomorphism and thereby risk (but also resist) reducing any notion of divine transcendence to human existence. Noting that Heidegger identifies human being with Dasein does not disqualify this basic point.

I agree with Abigail Rosenthal that authors deserve to be read charitably. As I tried to make clear, Wyschogrod remains a powerful and important Jewish thinker. But I also think that it is a sign of intellectual respect to take an author’s arguments seriously enough to think them through in ways in which an author may not have. As I wrote, Wyschogrod would and did want to resist some of the conclusions I draw about his thought. But wanting to resist particular conclusions is different from making arguments as to why such conclusions should not be reached. Unfortunately, I don’t think Wyschogrod’s thought has the resources to make these arguments.

A Pesca con Groucho

For a decidedly less analytical albeit funnier approach than Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: A Comedy of Existence (“Jews on the Loose,” Spring 2016)—although, well, who’s to say?—a version of Groucho’s existence exists that includes his very being being thrown out of hotels from West Virginia to Wyoming, check out his friend Irving Brecher’s memoir, The Wicked Wit of the West. (The title was Groucho’s non-chthonical nickname for Brecher.) Irv supplied funny lines for his pal in Go West and At the Circus. The book’s title was changed by the Italian publisher to A Pesca con Groucho due to a fishing trip the two men took just before Julius Marx landed the You Bet Your Life gig that paid for the rest of his, um, existence.

Name Withheld

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Groucho v. Schoenberg

Mitchell Cohen asks, “What was new in Schoenberg’s music?” (“A Dissonant Moses in Paris and Berlin,” Spring 2016) It seems to me that the answer is that by rejecting “traditional grammar” of musical language Schoenberg became musically antinomial at the same time that by converting to Lutheranism he became a Jewish antinomian. It is striking that he returned to the Jewish religion in which laws are meant to be observed and not broken, even though he never abandoned his musical antinomianism.

It is also curious that in this issue of the Jewish Review of Books Joseph Epstein in his article on Groucho (“Jews on the Loose”) rightly points out that it is wrong to ascribe antinomianism to the Marx Brothers. I think he is correct, but the glove fits with respect to Schoenberg’s music.

Gershon Hepner

via email

Correction: On page 6 of “Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love,” the word “not” was unintentionally omitted from a sentence. The sentence should have read, “In Wyschogrod’s words, Judaism ‘does not hear this [Christian] story, because the Word of God as it hears it does not tell it and because Jewish faith does not testify to it.’” We regret the error.

Suggested Reading

The Inklings

Leo Strauss may be as devastating as C. S. Lewis in his criticism of facile and destructive dogmas, but Hollywood isn’t planning a film version of Strauss’s Natural Right and History any time soon.

All-American, Post-Everything

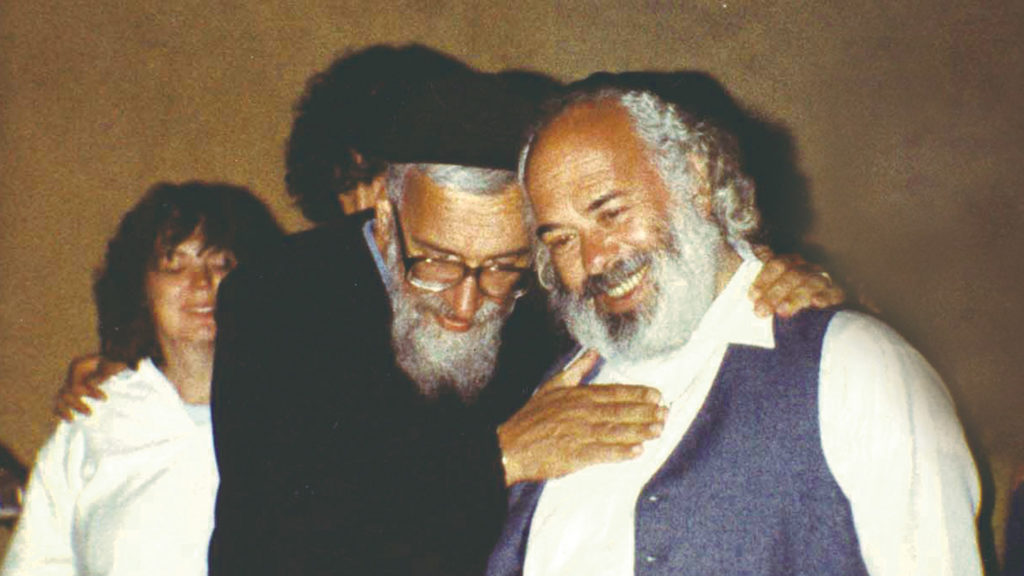

Shaul Magid argues that Zalman Schachter-Shalomi is the Rebbe for post-ethnic America. But is cosmotheism a good idea?

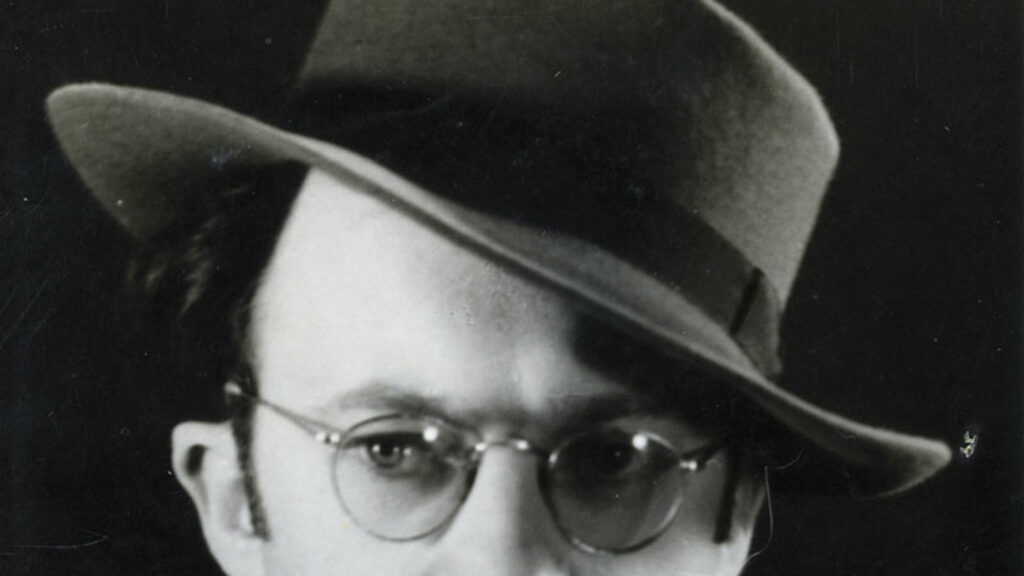

“With a Wolf in One Eye”: Sutzkever in Israel

From his birth just outside Vilna in 1913, Abraham Sutzkever led a life that had merged, as though on a God-ordained path, with the fate of the Jewish people in the 20th century. It of course follows that that life would reach its culmination in Israel.

Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto

The great poet Abraham Sutzkever once swore an oath to serve Yiddish culture. He fulfilled his vow in ways no one could have ever imagined.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In