All-American, Post-Everything

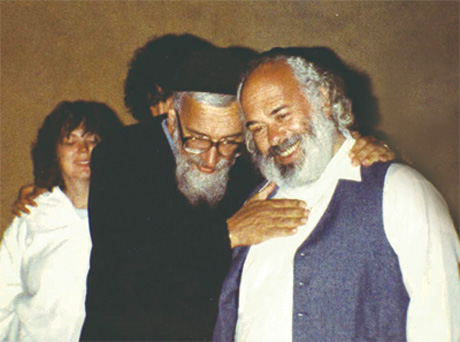

I made it through my last summer at Camp Ramah in Connecticut in 1964 without acquiring the ability to swim, but I did at least learn how to make a tallit. This was one of the things that Zalman Schachter (not yet with the hyphenate Shalomi) taught me and the other campers in a special club (or chug) that met two or three afternoons a week. We did some meditating and some traveling, too. I remember, most of all, a great eye-opening swing through Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey to visit, among other sites, a convent, an ashram, the offices of the Catholic Worker, and, of course, Chabad headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn (where Zalman, a wayward Lubavitcher, was still at least somewhat welcome).

In the years that followed, Reb Zalman, as he is commonly known, became the leading figure in Jewish Renewal, a movement in which I never took any part as an adult, not even on its fringes. But about ten years ago, I read for the first time a number of Schachter-Shalomi’s writings, and those of some of his colleagues and acolytes, after being asked to write an essay on Jewish Renewal for a volume titled Jewish Polity and American Civil Society. I subsequently described them, as my sole reviewer put it (in The Weekly Standard) in a “benignly satirical” manner.

If Shaul Magid also noticed this, it did not prevent him, in his newly published American Post-Judaism, from identifying my essay as “a useful assessment of Jewish Renewal.” This caught me by surprise, since the movement that I gently mocked is one that represents, to his mind, a guiding light for American Jews. But the further I made it into his book, the better I understood where we were in accord. We both view Renewal as a path away from Judaism as it has hitherto existed. The difference between us is that Magid, unlike me, believes that it has marked out the road that Jews ought to take.

Magid, by his own account, began life as a secular Jew, but became a ba’al teshuvah at the age of twenty under the tutelage of Dovid Din, “an obscure and enigmatic hasidic rabbi” who had been a student of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi back in the sixties. After attending a variety of yeshivas, Magid settled for three years “in a collective community in Israel founded by students of Shlomo Carlebach,” Zalman’s erstwhile spiritual companion. Eventually Magid left for academia. Now the Jay and Jeannie Schottenstein Professor of Jewish Studies at Indiana University, Magid has published numerous and valuable scholarly studies of Hasidism and modern Jewish thought. But he has not left Jewish Renewal behind. His first book was on the Hasidic thinker Rabbi Gershon Henokh of Radzin, whose work was prized by Carlebach and Schachter-Shalomi for its antinomian daring. In the present work, he moves beyond the Radziner, Carlebach (whose conspicuous absence throughout the book is only underlined by the seven-page Epilogue-cum-elegy devoted to him), and even Schachter-Shalomi. Magid argues that the Renewal movement’s “critique of Judaism and its constructive alternatives reach down to the very roots of Judaism and Jewishness, offering various ways to reconfigure Judaism for what I call a post-Judaism age, an age where Judaism remains related to but is no longer identical with Jewishness.”

American Post-Judaism fleshes out this claim with an account of Renewal’s basic orientation, as well as several extended discussions of issues that Renewal can help Jews rethink, such as the relationship of Judaism to Jesus and the significance of the Holocaust. Magid attempts to explain, in addition, why Renewal’s radical theology is singularly capable of“saving Judaism in America from obsolescence.” But his book leaves me no more convinced than I had been that Renewal is a genuine form of Judaism, one that preserves something more than some of its appearances. Nor does it lead me to believe that we are on the cusp of the “post-Judaism age” that Magid envisions.

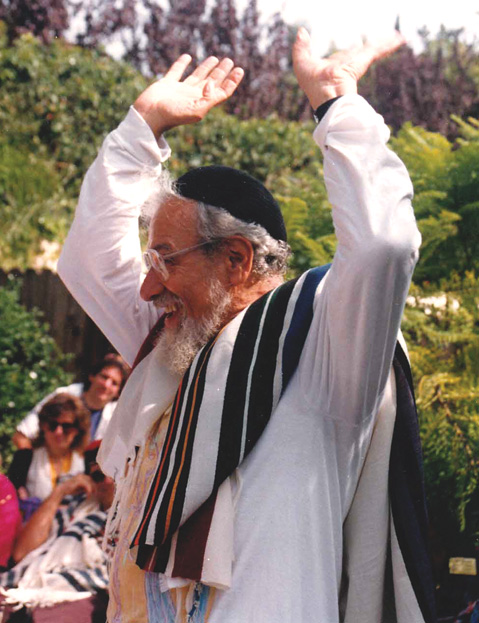

Such words may sound unjust to someone who has perhaps found himself or herself davening in a minyan that included “Renewed” Jews wrapped in huge, multicolored prayer shawls, swaying rhythmically and chanting rapturously. What right, one could ask, do I have to impugn such people’s piety? In fact, I don’t mean to do so. I readily acknowledge the authenticity of their religiosity, and I am less sure than Magid that it is as radically distinct from that of more traditional synagogue members as he suggests. I just don’t want to confuse Judaism and post-Judaism, a term that Magid has done us a service by inventing, even if he doesn’t use it consistently.

Even as he notes that Renewal’s critique of Judaism reaches down to its very roots, Magid reassures us that, “Post-Judaism is not the erasure of Judaism but a reassessment of some of the founding principles upon which Judaism was constructed.” At the same time, however, he insists that, “Renewal’s program is a radical departure from the very foundations of Jewish tradition.” None of the religion’s truly fundamental principles, it seems, survive reassessment, not even the most basic. The radical theology of Renewal goes so far as to subvert “the biblical monotheistic template” and replace it with something that can be identified as “cosmotheism.” This unfamiliar term is not Magid’s coinage, but one he borrows from Jan Assmann, for whom it represents, in Magid’s words, “a theological construct based on the premise that the divine world (the cosmos) and the world we live in are inextricably intertwined.” Cosmotheism “believes in a plurality of divine life in the world—and its accessibility to the human—focusing more on ritual, or cultus, than scripture or text.”

Nothing, it would seem, could represent a more complete departure from the very foundations of Judaism. True, Schachter-Shalomi “gestures,” as Magid puts it, “toward a cosmotheism that always existed in the Hebrew Bible and has survived as a repressed theology throughout most of Jewish history,” most recently in Hasidism. Yet Magid has his doubts about the real significance of such gestures. The “final act of erasure of classical theism in the form of biblical monotheism is perhaps,” he tells us at one point, for the Renewal theologians, “even more a product of the American religious context in which they live and think (theologically and politically) than the hasidic tradition that serves as the source of their inspiration.” Magid’s uncertainty on this score practically vanishes a few pages later, following his account of Schachter-Shalomi and Renewal theologian Arthur Green’s “revolutionary, metaphysical revision that serves as the basis for undoing much of what has been accomplished in historical Judaism.” Their work, Magid concludes, is “a serious revision—even a subversion—of classical Jewish metaphysics founded on American religious principles.”

But even if Schachter-Shalomi’s “post-monotheistic theology and Gaia-consciousness Judaism” are essentially reflections of the thinking of Ralph Waldo Emerson, William James, and New Age religious figures such as Ken Wilber, this clearly does not detract in any way, as far as Magid is concerned, from their legitimacy. Pouring new wine into old bottles is precisely what modern Jewish thinkers do. Canonical modern Jewish thinkers from Moses Mendelssohn and Hermann Cohen to Mordecai Kaplan have unabashedly upheld versions of Judaism that take their bearings largely from one or another or a medley of Gentile philosophers. Most of them, I would say, have done so with far more justification than the advocates of Jewish Renewal—but I’m not going to make that argument. What I think is worth asking in Magid’s case is why does he bother? Why isn’t it enough for Jews just to drink the new wine straight out of the American vat from which it comes?

The advocates of Renewal have to do a lot of work, after all, before they can refashion Judaism into a suitable receptacle for a postmodern American return to a pre-Mosaic cosmotheism. It’s not only the old metaphysics that has to be discarded, but “much of what has been accomplished in historical Judaism.” Magid doesn’t supply us with a comprehensive list of the things that have to be thrown out, but what he clearly regards as most objectionable are the laws that have kept the Jews in their “exclusivist cocoon.”

The Jews today constitute, in his opinion, “a people with no relevant halakhic anchor yet a community in need of a nomos with little precedent to guide her.” They are thus in need, according to Magid, of a new Judaism responding to a new era in human history (and not just Jewish history) that demands it to move toward the world rather than use halakha to protect itself from the world. By adopting a New Age post-millennial perspective, Renewal presents a Jewish vision founded on the very “un-halakhic” idea that Jewish nomos should be a way of breaking down barriers separating spiritual, ethnic, and national identities in order to foster a global consciousness that is founded on diversity with permeable boundaries. This includes, among other things, the creation of new rituals, conscious syncretism by utilizing practices of other faiths adapted to Jewish sensibilities and symbols, and the notion of inclusivity as a post-halakhic ideal.

This new and wide-open antinomian nomos, Magid believes, will not only revitalize the Jewish people but will be something of a magnet to outsiders as well. He is not looking for converts, but recommends that the people who come to it “because there is something about it, or about Jews, that is compelling” but who do not wish to convert “should be allowed to choose to take on aspects of Judaism and be considered part of the Jewish community.”

Magid is thus fully in accord with Schachter-Shalomi’s “principle that Judaism and Jewishness need not be fused.” What he does not explain is why they need to remain joined at all or why, in the new synagogue, the distinction between Jew and Greek has to be preserved. One also wonders why anyone would feel the need to enter the realm of Judaism in order to benefit from a religious message that has only recently been imported into it from other, more readily accessible territory. What might be the “something” in this new amalgam that such a person might find distinctively “compelling”? But this isn’t a very different question from the one we have left hanging: Why does Magid himself feel that the archaic and dilapidated house of Judaism should be so massively renovated instead of just being treated as a teardown?

One might not need to ask this last question if Magid followed Arthur Green in holding onto, in Magid’s words, “the mythic community of Sinai” and affirming the “mythic ethnos as having validity today.” But these are notions about which he expresses nothing but skepticism. Perhaps Magid is outlining his own position as well when he describes Schachter-Shalomi as believing that

The move to theological globalism is not meant to subvert particular communities from having their own distinct identities. Following Durkheim, this is a natural inclination of human civilization that cannot be usurped.

But even if one has a natural right to maintain one’s own distinct identity, one doesn’t necessarily have a duty or a reason to do so. The place of reason can be taken, however, by a wish. Magid is, by his own account, someone who remains “fascinated by, and deeply invested in, the complex nexus of Judaism and the American counterculture” in which he became enmeshed when he was young. At bottom, it appears, it is his own experience that has left him so strongly attached to what we might call cosmotheism with a post-Jewish face.

That traditional Jews will necessarily find such a blend altogether unacceptable goes without saying. But is there any reason why non-traditional Jews, including secularists, should respond in the same fashion? Why should they find Magid’s post-Judaism any less admissible than, say, Mordecai Kaplan’s Reconstructionism (to which Magid acknowledges a significant debt)?

For all his theological radicalism, Kaplan at least upheld a concept of Jewish peoplehood. His God may have been a purely notional being, but he defined the Jews as “an international nation, functioning as such by virtue of a common past, their aspiration toward a common future and the will-to-cooperate in the achievement of common ends.” Magid emphatically rejects any such idea. That the Jews, “whether in the Diaspora or in Israel, are one people and thus the drama of one Jewish society is the drama of another,” is, in his opinion, “a myth that is less and less convincing.” Kaplan saw the Jewish homeland as “the symbol of the Jewish renascence and the center of Jewish civilization” throughout the world. According to Magid, the Jews of Israel, the only other Jews in today’s world to whom he gives any consideration, live in a country that “is increasingly becoming its own Jewish civilization,” one which is of marginal concern to him in this book and to which he pays attention mostly for purposes of (generally invidious) comparison with the United States. The eyes of the author of American Post-Judaism are focused far more on Gentiles in this country’s “postethnic society” than on Jews elsewhere, for in his scheme of things, they have a much more important role to play.

Magid doesn’t think that ethnicity has disappeared or will disappear in America, but he does believe, following the historian David Hollinger among others, that it “will become something other than purely a consequence of ascription or descent.” What we now see coming into being, largely as a result of massive intermarriage, are “new ethnicities that are created by a combination of descent and consent, ascription and affiliation.” Postethnic America therefore “presents serious challenges to the continuity and survival of Jews and Judaism precisely because it undermines the very notion of ethnicity that served Jews as an anchor for most of its history.”

Magid mentions people such as Alan Dershowitz and Elliott Abrams who are deeply dismayed by this state of affairs and seeking to alter it by various means, but gives them very short shrift. Their proposals are futile, he writes. They ought to realize that “postethnicity is with us for the foreseeable future.” The Jews must therefore “learn how to think within its boundaries and not simply deny its existence or remain wed to old-paradigm ‘oughts’ in order to create models for survival, continuity, and renewal.” It is easier, no doubt, for Magid to adapt to this new situation than it is for the other writers he mentions, for he doesn’t find it unwelcome in the way that they do. Given his overall theo-political outlook, he has good reason to consider it desirable. If intermarriage rates were in fact to decline, he might even consider such a development to be a regrettable sign of the Jews’ retreat back into their “exclusivist cocoon.” It will surely be easier to foster the kind of new rituals and conscious (yet somehow controlled) syncretism that Magid recommends in communities devoted to post-Judaism that include many non-Jewish members.

Like Schachter-Shalomi, Magid wants a renewed Judaism “to participate fully in the global concern for the well being of the planet and all its inhabitants.” He wants its “resources, insights, and teachings” to “contribute to the larger humanistic concerns of the day.” Today, Magid acknowledges, Renewal is still mostly confined to a “fairly small group of alternative communities scattered throughout the landscape of North America.” But he is very hopeful about the future. He believes that “American Jewry and Judaism are in the midst of a systemic shift in identity, belief, and practice, the effects of which will be felt for the next few generations” and that things may be moving in the direction that he desires.

Things look different to me. My guess is that the Renewal communities will remain the marginal phenomenon that they have been for decades, as often as not an entry point to more mainstream forms of Judaism. But even if they grow much larger, I do not believe that they will become a dominant element in the future of American Judaism, especially if they follow the path that Magid has marked out. If that is where they choose to go, I believe, they will stray further and further from other Jews, and eventually merge with cosmotheists of other stripes, their real spiritual kindred.

The publication of American Post-Judaism was supported, as a stand-alone page in the front-matter proudly announces, by a grant from the Jewish Federation of Greater Hartford. Reading this, I couldn’t help but recall the way Stephen King began his commencement speech at Vassar in 2001: “You here at Vassar have invited the man most commonly seen as America’s Bogeyman . . . and I have to ask you: What were you thinking? What in God’s name were you thinking?” What, indeed, were the people at the Jewish Federation thinking when they proffered this subvention? Did they have any idea how radically subversive of both monotheism and worldwide Jewish solidarity its recipient would aim to be? My guess is that they did but they weren’t too troubled by such matters. I can readily imagine that they see Magid’s ideas as a relatively harmless means of rescuing a few stray young souls from whatever other postethnic, New Age alternative might otherwise be in store for them.

- Shaul Magid furthers his case out a case for “bothering” with Jewish Renewal in his response to this review.

- In his rejoinder, Allan Arkush maintains that Renewal is a road away from Judaism, not a path toward the future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

North Africa during World War II

Mentions of wartime North Africa conjures up visions of Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains in Casablanca. It was far worse than that...

The First Amendment and the Vocabulary of Freedom

Oral arguments in a case involving two Catholic schools sometimes sounded less like a jurisprudential clash over the First Amendment than a synagogue kiddush.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

Starving for Zion

For Chaim Gans, the justification for nationalism in general, and Zionism in particular, lies in the human rights of the individual.

SDK

Huh. I had no idea there was so much theology there. I just thought they were really good at daavening, kavannah, and very open to actually talking about their relationships with God. Regardless, when you pray with a group of people who have that connection, it's pretty clear that they're not just singing kumbaya.

Maybe if Arkush had attended some tefilot instead of reading theology, he would have a different opinion.