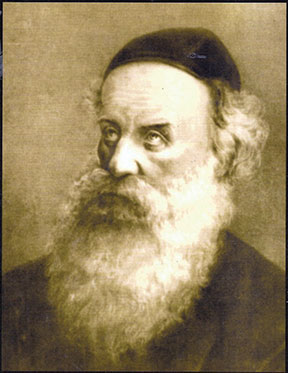

The Alter Rebbe

The late Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson fondly told and retold many stories about his illustrious ancestor Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, the founder of the Chabad Hasidic dynasty. One favorite was set in the period when his married son Rabbi Dov Ber came to live with him. Both devoted themselves to studying Torah, but they often did so separately, with Rabbi Dov Ber on the lower floor, together with his family, and Rabbi Shneur Zalman upstairs. Once, Rabbi Dov Ber’s youngest child began crying, but his father was so engrossed in his sacred study that he didn’t notice. Although he was also in the midst of deep study, Rabbi Shneur Zalman rushed downstairs and berated his son for having allowed the cloak of piety to render him oblivious to his child’s suffering. This story, which Rabbi Schneerson reported hearing from his father-in-law, the previous Rebbe of Chabad, embodies what he saw as the fundamental commitments of the Chabad ethos: absolute, unflinching devotion to study paired with an ever-present attention to the needs of others. This spiritual vision of Chabad, to which Rabbi Menachem Mendel was the most recent heir, was born in the teachings of Rabbi Shneur Zalman.

Immanuel Etkes is a distinguished Israeli historian with a gift for integrating the intellectual and social history of 18th– and 19th-century Eastern European Jewry, and his newly translated biography of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, sometimes referred to as “the Alter Rebbe” (the old Rabbi), is a brilliant accomplishment, both critical and deeply sympathetic. Of his subject, he writes:

[H]e was a rabbinic scholar; a deep and original thinker; and a talented preacher, educator, and administrator. In addition, he had a deep sense of mission, firm confidence in the rightness of Hasidism, and great sensitivity to the needs of the Jews in the Russian Empire. Moreover, he possessed courage, authority, determination, and self-control.

Drawing on a variety of letters, archive documents, and Hasidic texts to supplement several decades of research, Etkes has painted a broad, contextual portrait of this exceptional spiritual master, addressing issues ranging from the organization and governance of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s Hasidic court to some key aspects of his mystical teachings.

Such a project necessitates sifting through many layers of hagiography, which Etkes has done with great care. We meet the young Shneur Zalman shortly after the death of his master Rabbi Dov Ber Friedman, known as the Maggid (or preacher) of Mezheritch in 1772. At this point, Rabbi Shneur Zalman became a student of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, an older member of the Maggid’s circle. In 1777, Rabbi Menachem Mendel and his younger colleague Rabbi Abraham of Kalisk led several hundred Hasidim to the land of Israel, eventually settling in Safed, which was then part of Ottoman Syria. Over the next few years the two of them gently persuaded Rabbi Shneur Zalman, who had remained in White Russia, to act as their proxy.

In addition to providing spiritual and intellectual guidance to the Hasidim his colleagues had left behind, Rabbi Shneur Zalman developed and oversaw the fundraising network which supported Hasidic life in the Holy Land. Gradually, perhaps inevitably, Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s independence increased. He matured as a leader and thinker, and, at the same time, it became clear that the Hasidim in White Russia could not maintain sole allegiance to two absent leaders. By the time of Rabbi Menachem Mendel’s death in 1788, Rabbi Shneur Zalman was poised to become the most important Hasidic leader in White Russia.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman took an active part in the controversy with the mitnagdim, the rabbinic opponents of Hasidism, who banned and persecuted Hasidim for perceived social, halakhic, and theological offenses. As a result of charges laid against him by the mitnagdim, Rabbi Shneur Zalman was twice imprisoned (in 1798 and 1800) by the Russian authorities on suspicion of sedition, religious factionalism, and misappropriation of funds. While in prison, he was interrogated, and the lengthy Russian transcripts provide a unique window into his understanding and practice of Hasidism. In both cases, he and his followers were vindicated by the Russian authorities.

Over the course of the 1790s Rabbi Shneur Zalman established a sophisticated and highly centralized Hasidic court. His was not the first institution of this kind, but it was the most complex and finely tuned. The numbers that flocked to hear him preach were so great that he was forced to enact a series of policies regulating the flow of visiting Hasidim who visited Liady. Etkes argues that Rabbi Shneur Zalman built on the model established by his teacher, the Maggid of Mezheritch, of whom he writes:

[T]he Maggid did not engage in magic, did not perform wonders, and did not take care of the worldly troubles of the people. His decisive contribution to the development of Hasidism was expressed in the formation of the Hasidic court as the center of spiritual and religious activity. This move was closely connected to changing Hasidism from a limited group of mystics into a growing movement that swept

up many of the Jews in Eastern Europe.

In broad strokes, this is true, but such generalizations do not address the complexity of the Maggid’s attitude toward miracles and wonder-working or the innovative elements of the Maggid’s theology in relation to the ideas of the putative founder (and wonder-worker) of Hasidism, the Ba’al Shem Tov. Perhaps most importantly, they elide the fact that there is no clear notion of the tzaddik as community leader as well as spiritual virtuoso in the teachings of the Maggid. The Maggid was the master of a loose-knit group of intellectual and spiritual disciples, but he was not a communal leader of the sort that emerged in the Hasidism of the 1780s and 90s.

However, Etkes is correct about the innovative aspects of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s finely tuned and elaborate system of governance, including disciplined fundraising, strict rules regarding visitation, and a network of spies to ensure that those in the periphery of his orbit remained faithful to his edicts. The community founded by Rabbi Shneur Zalman remained among the most tightly and successfully administrated Hasidic groups throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was, of course, this system that Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson inherited and turned into one of the most extraordinary religious organizations of the 20th century.

Etkes also identifies Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s unique spiritual-religious ethos. In doing so, he devotes most of his attention to the first section of Likkutei Amarim-Tanya, published anonymously in 1796. Tanya is, by any standard, an exceptional book. Most Hasidic works from this early period are either loose compendia of teachings or anthologies of sermons. The core of Tanya is, in contrast, a carefully constructed theological treatise explaining the inner workings of the Godhead, the nature of the human soul, and the complexities of attaining spiritual uplift in Divine service. This mystical system is grounded in the theories and terminology of Safed Kabbalah and emphasizes the power of intellectual contemplation in the study of Torah for cultivating devekut, or mystical communion with the Divine.

The Hebrew version of Etkes’s book appeared in 2011, and, sentence for sentence, Jeffrey Green’s translation is excellent. However, significant elements (including several important chapters and appendices) have been lost in translation, presumably due to the exigencies of space. Unfortunately, one of these is Etkes’s discussion of Sha’ar ha-Yichud ve-ha-Emunah, the second part of Tanya and one of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s richest and boldest theological expressions. The fact that this section was removed, as opposed to synthesizing or omitting one of the three long chapters on his conflict with the mitnagdim, tips the balance of the English book too far to the side of social rather than intellectual history.

Also present in the original but not sufficiently treated in the present book are Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s other writings. For instance, Etkes does not take up the way the major themes of Tanya were expanded upon, sometimes also challenged, and even inverted in the hundreds of sermons attributed to Rabbi Shneur Zalman, nor does Etkes consider his legal writings. The decision not to engage with these primary sources means that Etkes’s image of Rabbi Shneur Zalman is only a partial reconstruction, for the social and intellectual aspects of his life were deeply intertwined. Restricting the analysis of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s teachings to the first part of Tanya does not allow us to chart how his thinking on key subjects such as the nature of leadership and communal prayer may have evolved over time. It also leaves open the question of whether the homilies delivered on dates when all of his Hasidim were present at the court differ in some way from those given to smaller audiences throughout the year.

A developmental study of Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s thought, together with Etkes’s peerless historical account of his life and times, would prepare us for yet another important scholarly project in uncovering the intellectual origins of Hasidism: understanding the place of Rabbi Shneur Zalman as an interpreter of the Maggid’s theology. The reader should note that the relationship between these two great figures is a major subject in the Hebrew edition, making its absence in the English version all the more conspicuous. Etkes himself suggests that:

[D]espite the splits and variations, Hasidism was regarded by its leaders, and most likely by the community of Hasidim as well, as a single movement that drew on common sources and a shared tradition. Hence, the legitimacy of its leaders depended on their commitment to that tradition.

I’m not sure, however, that things are quite this simple. Rarely in early Hasidic texts does one see an attempt to trace ideas back to the “founding father” in order to ensure their legitimacy. Moreover, while Etkes is certainly right that early Hasidim shared an intellectual and spiritual legacy, there were dramatic disagreements between Rabbi Shneur Zalman and many other Hasidic leaders who had studied with the Maggid, which Etkes does not explore.

Thus, in a chapter titled “Zaddikim as Human Beings,” Etkes describes the highly public and acrimonious controversy with Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s former patron Rabbi Abraham of Kalisk as being largely motivated by a contest as to who was the ultimate spiritual leader of the Hasidim of White Russia and, even more, as a struggle for control of the fundraising network that had been established to support the Hasidim of the Holy Land. This is, no doubt, true, but human beings fight over ideas and beliefs as well as money and hurt feelings. Etkes does not deny this, but he speaks of their ideological dispute as “secondary.”

And yet, Rabbi Abraham of Kalisk was right in claiming that Rabbi Shneur Zalman was doing something new and unique. This includes his establishment of a hierarchical Hasidic court and a rigid social architecture; his definition of the tzaddik as innately, qualitatively, and unattainably different from all other Hasidim; his rigorously Lurianic presentation of the teachings of the Ba’al Shem Tov and the Maggid; and his relentless focus on intellectual contemplation. With regard to this last point, Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s approach to the inner life might be summed up in his own words: “the mind rules over the heart.” But the notion that the intellectual faculties were the necessary point of departure and the guiding force of all successful spiritual meditation was hardly agreed upon by others in the Maggid’s circle. Here are the words of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, Rabbi Abraham of Kalisk’s fiercely ecstatic colleague:

One cannot attain or grasp the true attachment to the infinite One by means of the intellect (ba-sekhel), and all the more so [is it impossible] through feelings of pleasure [. . .] But it is true that the only way to arrive at faith and attachment [to God] is [. . .] through love, and fear [. . .] This [work] is preparation, a platform for attaining the Unknowable (ha-eino musag), the primary goal that comes only later [. . .] The sages refer to the early pious ones, who meditated for three hours in every prayer service. They arrived at attachment, faith and total self-nullification for nine hours per day. But this is why the Talmud challenges, “When will their study and their work be done?” This question refers to their emotive faculties (middot), called “holy work” [. . .] for it is they that lead one to attachment [to God].

Spiritual work, according to Rabbi Menachem Mendel, had to begin with the emotions and not the mind. In the Tanya, his erstwhile student taught the opposite.

As I noted, the Tanya was the first true book of early Hasidism, as opposed to a compendium of sayings or sermons. What motivated Rabbi Shneur Zalman to write it, given that early Hasidism was primarily an oral movement? Like many thinkers, he was unhappy with imprecise accounts of his teachings in circulation, but, as he writes in his introduction, he was also overwhelmed by the crushing numbers of disciples seeking his counsel. As Etkes puts it, “The book was meant to replace, to a certain degree, the personal audience with the Zaddik.” Close disciples were meant to share their understanding of its content with others, establishing a network of reading groups poring over Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s words. The intensely intellectual spiritual path described in the Tanya, together with the great appreciation for the study of Torah, might also have been an implicit response and appeal to the mitnagdim, who tended to regard Hasidism as a movement of enthusiastic ignoramuses.

This is not to say that Rabbi Shneur Zalman thought writing could replace oral instruction. He never relinquished his role as a communal preacher, and his public sermons—unpublished in his lifetime—were a key element of his project. Moreover, his letters, like those of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and Rabbi Abraham of Kalisk, were accompanied by messengers who would impart another layer of the message orally. At times this was sensitive information that was left unwritten for reasons of confidentiality, but in other cases the accompanying oral message was personal spiritual instruction that could not be captured in writing.

Etkes concludes his biography by noting that “the Hasidic ethos that [Rabbi Shneur Zalman] created and shaped” was preserved and passed down for almost two centuries. This is precisely right, and recognition should be extended to his impact on the development of Hasidic theology as well.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady died in 1812 as he was fleeing into Russia in advance of the invasion of Napoleon, whom he had opposed in favor of the tsar. His son Rabbi Dov Ber took charge of the community after a struggle for succession with a student of his father’s named Rabbi Aaron ha-Levi Horowitz of Staroselye and moved the court to the Russian city of Lubavitch. Rabbi Dov Ber’s ascent heralded the beginning of a familial dynasty that endured until the death of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh and final Lubavitcher Rebbe, in 1994.

Suggested Reading

The Medieval Blueprint: A Rejoinder

Alexander Kaye understates the extent to which medieval Judaism gave rise to the idea of a halakhic state.

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

Lands of the Free

It is sad to watch the territorialists engage in their wild goose chases all over the globe at a time when multitudes of Jews were in need of a place, any place, to go.

History of a Passé Future

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In