A Stolen Seat

Among the narratives of late 19th– and early 20th-century shtetl life—the bitter and the sentimental, the fictional and the historical—Doba-Mera Medvedeva’s stands out. Her memoir is unusual not only because she was a woman, but because she was barely educated. While still a girl, she worked as a men’s tailor, moving from shop to shop, finding kindness on occasion and exploitation almost always. Her observations are detailed and sharp. Her ability to size up a situation helped her navigate a life that was constricted by poverty, revolution, and war.

The shtetl of Doba-Mera’s memoirs is Khotimsk, in the Klimovichi district of the Mogilev guberniia, now Belarus. It was a remote backwater, but ideas travel, and her father was a maskil, an adherent of the Jewish Enlightenment, who taught for a living and for a time included his daughter in the lessons. The death of his wife, Doba-Mera’s mother, was catastrophic. Two little boys were orphaned along with Doba-Mera. A stepmother, brought in to control the chaos, made it worse.

But a story of emotional and physical hardships is not the entirety of what she left us. When she sat down to write in the Soviet Union of the late 1930s, one of her main goals was descriptive, so her memoir answers many questions that other accounts slide by. How did loans work in a shtetl? How did a sick person without money get care at a hospital? How did a girl working at her sewing machine interact with her employer’s wife in the kitchen two steps away? Where did apprentices eat, how did they get tipped, and what did they do with the money? And finally—something described elsewhere, but always interesting—how did courtship unfold as parents lost authority? A writer without schooling, she created what anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously called call a “thick description”—a gift to scholars and readers.

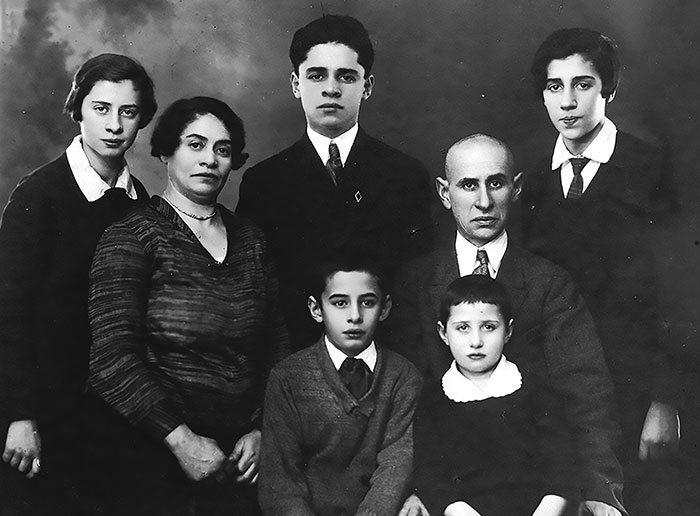

Doba-Mera, born in 1892, began her handwritten notebooks when she was 47. Thinking of her Russian-speaking grandchildren, she wrote in that language, which she knew imperfectly, rather than her native Yiddish. After her death, the notebooks were passed on to a grandson, the Israeli historian Michael Beizer, who published them in a Russian journal. Our English translation, published under the title Daughter of the Shtetl: The Memoirs of Doba-Mera Medvedeva, from which the selections below are taken, ends in 1944.

The sections excerpted here are about the synagogue as a battleground between rich and poor—though Khotimsk’s rich didn’t have that much more than its poor did. “[T]he rich don’t like to help their own families any more than they like to help strangers,” she writes, before describing the economic disparities in her own family. Here, a rich uncle named Alter, husband to her father’s sister, not only doesn’t alleviate her family’s poverty, he exploits it. Doba-Mera’s vaguely Marxist take on the class struggle is an inheritance of her years—the happiest years of her life—spent in Yiddish-Marxist revolutionary circles. It is also a product of her impoverished circumstances and tsarist imperial law, under which shtetl dwellers lived a zero-sum existence.

Against the Marxist grain, Doba-Mera’s stories often show a significant degree of Jewish communal solidarity. When her father gets sick, relatives give them money to travel to the Jewish hospital in Kiev. A Jewish network somewhat grudgingly helps them and protects them from the police (Kiev was outside the Pale of Settlement). Doba-Mera describes this without comment: Her world is still split between rich and poor. It is only in late 1941, when she learns about the death of everyone she knew, including the stepmother she hated and the stepsister who barely figured at all, that her class consciousness evaporates along with her grievance. “Everybody was a blood relation,” she writes. “My heart broke into pieces.”

My father was the head of the family, as was the custom in the olden days. He was very educated for his time, both in Jewish subjects and in Russian; he could read Latin. He took a great interest in politics and subscribed to the newspapers that were available then, as far as I can remember—Der Fraynd, Ha-Melits, and others—which was unusual for a shtetl in the middle of nowhere. His beautiful curly auburn hair and beard made him look more like a poet than a melamed. He knew a lot of mathematics, and young people who hoped to pass “extern” exams for the gymnasium [preparatory school] would come for help in solving problems when they got stuck, and he would always help them.

He didn’t like rich people. When he was in the synagogue, he didn’t want to sit in a place of honor—that is, by the mizrah, the eastern wall. He always found a place with the artisans and the paupers, who sat in the middle of the synagogue and by the doors and the reading stand in the center, since paupers and artisans were not allowed in the place of honor. It sometimes happened that a wealthy artisan would buy a seat by the mizrah, at which point his wealthy neighbors would run away from him. And then there would be an uproar in the synagogue, both from the rich men and from the artisans and paupers, who would shout “They don’t like us! Our money is treyf, because we earn it by our labor.” The commotion would continue until the leaders of the synagogue (respected people, the heads of the Jewish community) would intervene and decide either to give the artisan back his money and leave the seat to the synagogue or make the rich man who couldn’t stand his new neighbor buy the seat from him and keep it for himself. At that point the obedient artisan would take his money and rain down all the curses he knew on his neighbor and the whole community, saying, “I don’t even want to sit next to people like that.” Or “You don’t want me? You have an aversion to artisans? I’m no thief; I’ll take you to court.” And the affair would end up in court, before the head of the local zemstvo [rural self-government body]. Whichever side could buy the judge off, that side would win. But if the place was awarded to the artisan, then usually either the rich man would leave or he would make peace with his new neighbor.

Alter’s first move was to take away my father’s seat in the synagogue. Of course, the way I look at things, both now and earlier, and in the opinion of many people, there’s nothing remarkable about that: “Big deal. So he took away your seat in the synagogue. You can go to synagogue without a seat, or you can not bother going at all.” But that’s how people think now—back then it was completely different. As I already wrote, my father rarely used his seat, because he preferred to be with poor people, so he usually walked about the synagogue. When his brother-in-law Alter first appeared, my father seated him in his own place, as a brother and a guest. Alter responded by taking the seat over from the very first day. When my father would arrive and try to take his seat, Alter would try not to notice him, pretending that he was deep in prayer, or he would simply not let Father sit down. Finally he declared that the seat was part of his, Alter’s, dowry, and Papa retreated quietly, so people wouldn’t hear. For my father, this was a huge blow. Most important, the seat had belonged to his own father, whom he loved very much and respected for his education. To make matters worse, people started to make fun of him, saying that he couldn’t stand up for what was his. A lot of people invited him to sit in their seats, but he didn’t want to take over the places of other people. At that time, according to Jewish tradition, seats in the synagogue went from father to son, not to a daughter, because women didn’t pray together with men. From the moment that his brother-in-law took over his synagogue seat, my father hung out with the paupers, partly because he always enjoyed talking with them and partly because he had no other place to sit. At that time to pray in the synagogue without a seat was the same as going someplace you weren’t wanted. He didn’t have the money to buy another seat, and in any case he would have been ashamed to do that in front of his acquaintances.

In this way Alter entered our lives. Knowing this one thing is enough to understand how his mind worked. When I grew up, I came across a novel in Yiddish called Der shvartser yungerman [written by Yankev Dinezon, 1877]. It describes how a son-in-law was taken into a home, and how little by little he took control of everything and everyone and sent everyone to their graves, so nobody would disturb him. The hero of this book reminded me a lot of Alter, and I shed a lot of tears over it. This book clearly showed me Alter’s true face and his ugly deeds and the role that he played in our family. Even so, to this day he doesn’t consider himself guilty. After he took over the seat in the synagogue, he decided to dispense with my parents and take over the entire inheritance, even though it was small. He relied on help from my step-grandmother, who had no love for my father as a stepson, and met no resistance on the part of my parents, whose honorable nature he abused.

Suggested Reading

Bellow, Broadway Billy, and American Jewry

As Mark Cohen’s new biography reminds us, “Broadway” Billy Rose was America’s master showman for a quarter of a century. When a friend told Saul Bellow how Rose had saved a fellow Jew from an Italian prison in 1939 but refused to speak with him afterward, Bellow knew he had a story.

Tough Bananas

A rags-to-riches tale with a machete-swinging Jewish hero.

How Jews Were Modern

What’s a nice Jewish boy doing making bronze statues of tsars? And does it count as Jewish culture? Ahad Ha’am wanted to know and the Posen Foundation’s ambitious new survey raises the question afresh.

The Great Family Circle

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, “the father of modern Hebrew,” famously raised his own son to be the first child in almost 2,000 years to speak only Hebrew. When Itamar Ben-Avi grew up, he was fascinated by . . . Esperanto. Esther Schor’s new book on L. L. Zamenhof, his would-be universal language, and those who still speak it inspired Stuart Schoffman to revisit the oddly parallel careers of Ben-Yehuda and Zamenhof.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In