Promised Land or Homeland?

Rather surprisingly, the university presses of Cambridge and Oxford have provided us with two new works of Jewish political theory that blend theoretical defenses of Zionism with robust critique of what Chaim Gans calls the “Zionist mainstream.” In Zionism and Judaism, David Novak, a traditionalist rabbi and distinguished professor of Jewish thought at the University of Toronto, argues that the foundation of Zionism must be theological. For Gans, a professor of law at Tel Aviv University and a prolific writer on nationalism, the failing of the Zionist mainstream is not its secularism but rather its inability to shed an ethnocentric myth that has prevented Israel from according the Arabs numbered among its citizens, or who live under its control, full justice. In A Political Theory for the Jewish People, he tries to do so without sacrificing Israel’s identity as a Jewish state.

Novak has written his book because “the legitimacy of the State of Israel, the object of the Zionist project, is under philosophical-theoretical attack, especially by those who argue that Zionism is antithetical to Judaism.” Precisely whom Novak has in mind here is something about which he does not choose to enlighten us. He never cites or even names any of the assailants, nor, for that matter, does he present a philosophical-theoretical response to any of the arguments being made these days by critics of Zionism, post- or just anti-. He does pay some attention to Yoel Teitelbaum, the most articulate and influential exponent of a theology holding Zionism to be a perversion of Judaism. But Novak hasn’t done anything as pointless as writing Zionism and Judaism to respond to the arguments of the late Satmar Rebbe. It seems, rather, that Novak believes that the only effective way to parry the ongoing but unidentified philosophical-theoretical attack on Zionism is through Jewish theology.

In a manner somewhat reminiscent of the thinker from whom he takes an important cue, Leo Strauss, Novak tries to show the inherent insufficiency of secular Zionism in both its political and its cultural forms. For Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, he writes, anything other than the defiant assertion of Jewish independence was of secondary importance, “if not negligible altogether.” This isn’t really true, of course, of Herzl, whose social ideals are well known. Novak, however, is confident that his brief sketch of Herzl’s views and his even briefer references to some of his successors have shown that political Zionism is “still too negatively motivated to provide enough of a positive purpose for the State of Israel, and for our support of the State of Israel as Zionists.”

This was, to some extent, also Ahad Ha-Am’s criticism of Herzl and political Zionism. His cultural Zionism was an attempt to link the return to Zion to an effort to preserve Judaism as the product of Jewish “national creativity,” rather than a revealed religion. But Novak finds this replacement of divine dispensation by man-made culture to be a “modern version of idolatry.” Moreover, insofar as cultural Zionism treats the Jewish “national spirit” as the moral equivalent of other peoples’ national spirits, it “seems to suggest polytheism: the assertion that there are many gods.” Ahad Ha-Am himself would have recoiled from such an indictment (as do I), but the notion of a “national spirit” is, Novak asserts, one that “has to be taken to be polytheistic, whether he could admit that or not.”

What follows, Novak says, from the emptiness of political Zionism and the heresy of cultural Zionism is that the only “cogent” Zionism “is religious,’ stemming from some kind of theological-political Jewish worldview.” It is here that he footnotes Strauss’s famous preface to the English translation of his book on Spinoza, in which he first builds cultural Zionism up, stating that “the Jewish state will be an empty shell without a Jewish culture which has its roots in the Jewish heritage,” and then tears it down by maintaining that “[w]hen cultural Zionism understands itself, it turns into religious Zionism.” Unlike Strauss, however, Novak proceeds to outline and defend a religious Zionist world view.

Near the beginning of his chapter on “the primacy of theology,” Novak grants “[r]eaders who are anxious to get to the point about Zionism more quickly” permission to skip his extensive “metaphysical discussion.” In view of his promise that they can do so “without losing the train of thought of the overall argument of the book,” I will take him up on the offer. In order to understand his view of the relationship between Zionism and Judaism we need only to know that his reflections lead to the conclusion that “the people Israel need a place to call home in this world, a place in which to center the God-Israel covenant” regulating Israel’s life, and the place that God has given it is the Land of Israel. Novak therefore identifies as “Zionism’s true goal” the ultimate establishment in the Holy Land of a Jewish theocracy. But this does not lead him to advocate, as the religious Zionist slogan has it (in his translation), the present governance of “the land of Israel for the people Israel according to Israel’s Torah.” Why not?

For a definition of theocracy, Novak turns to Spinoza, who identified it (while by no means endorsing it) as a state whose “citizens were bound by no law but the Law revealed by God.” In attempting to elucidate the implications of this definition, Novak does not dwell on the Law itself but on the citizenry who must accept it “because it comes from God.” In the absence of such a citizenry, Novak argues, there can be no true theocracy. Thus, “a dictatorship of rabbinical clerics” or a regime representing “the special interest of a particular party that promotes the political power and welfare of a group of people who happen to be ‘religious’ or dati” is not a genuine theocracy. No one, Novak insists, should attempt to impose divine law upon a populace—like that of Israel today—that consists mostly of Jews who haven’t accepted the Law’s authority. Religious Jews, then, should not “fight for an halakhic state, or even [. . .] religious control of state institutions.”

This should not, however, lead faithful Zionists to resign themselves to a Jewish State without theological foundations. Rather than surrender the Israeli public sphere to secularists they must ask the following, all-important questions:

Does the Jewish tradition have a secular law (or at least an idea of secular law) that is neither atheistic, which would be antithetical to the Torah, nor specifically religious, which would require a complete halakhic polity to interpret it, administer it, and even enforce it? Can we find in the Jewish tradition an affirmation of a secular realm that is based neither on dogmatic secularism nor on the particular revelation of the Torah (i.e., Jewish religion) to the Jewish people, claiming both the people collectively and each and every Jew individually? In other words, can we find in the Jewish tradition grounds for asserting a theistically based polity, which is presupposed by, yet not identical with, the optimal theocratic polity the Torah seems to be intending for Israel? Furthermore, could this Jewish secularity be the basis for a truly democratic polity in Israel? And, could this democratic secularity guarantee to secular Jews that it has good reason to eschew any coercion of religious belief and religious practice?

The answer to all of these questions is yes! There are the Noahide laws, prescribed by God for all humans prior to the giving of the Torah (according to Jewish tradition). They prohibit idolatry, blasphemy, murder, sexual license, and robbery, and in addition command the establishment of a legal system that enforces these norms. At bad times, like the present, when it is unable to enforce much of Jewish law, the Jewish polity ought to fall back on this earlier, more rudimentary legislation. “These laws,” Novak writes, “guarantee basic human rights. As such, their public affirmation by a Jewish polity is the best foundation of a state that is both Jewish and democratic.”

The “theistically based polity” founded on such an affirmation might be easier for secularists to accept than a full-fledged theocracy, but it is still antithetical to their basic principles. It would compel them to relinquish the idea of a constitution that sees “the prime authority of the state to be the will of a group of human beings.” Novak nevertheless urges them to respond positively to the proposal and “develop a Zionist philosophy that can basically accept divine sovereignty (malkhut shamayim) as the state’s warrant, yet without requiring secular Jews to personally accept revealed law as normative in their own personal lives or that Jewish religious practices must be enforced in public.” He knows that he is asking a lot, but he thinks it is a price in authenticity that secular Zionists ought to be willing to pay in order to “alleviate the deep Kulturkampf that divides Israeli Jews, and that has severe repercussions among the Jews in the Diaspora too.”

Novak’s new proposal brings to mind Menachem M. Schneerson’s successful (if far from epoch-making) campaign to get President Ronald Reagan to issue a proclamation acknowledging “the historical tradition of ethical values and principles, which have been the bedrock of society from the dawn of civilization when they were known as the Seven Noahide Laws, transmitted through God to Moses on Mount Sinai.” But Novak, it seems, wants more than the Rebbe, more than a symbolic political declaration from the highest authorities. He discusses this matter in close proximity to his critical treatment of Israel’s Basic Laws and apparently wishes to see the Noahide laws somehow incorporated into them.

Is this something that the Jews of Israel would be likely to welcome? Novak clearly wants them to believe that at the very least they would have nothing to lose if they did so, since all of the Noahide laws serve to protect the individual rights that are so precious to them:

Thus murder is prohibited because every innocent human being created in the image of God has the right not to be killed. Thus sexual license is prohibited because every human being created in the image of God has the right not to be sexually violated. Thus robbery is prohibited because every human being created in the image of God has the right not to have his or her property misappropriated.

But is it an accident, we must ask, that Novak has omitted any mention of idolatry and blasphemy from this Noahide bill of rights? These are, after all, by far the most problematic prohibitions for a modern state. What are Israeli pagans (there are a few) to think of the proposal to outlaw their religion? Much more important, wouldn’t the prohibition of idolatry and blasphemy threaten to curtail the free expression of anti-clerical writers and atheists and even—on Novak’s analysis—cultural Zionists? And wouldn’t Israeli homosexuals (not to speak of consenting adulterers) have good reason to fear that the Noahide law against sexual license would be interpreted in ways that would deprive them of their freedom?

In addition, wouldn’t a considerable number of Israeli Jews, if not a majority, have reason to be concerned that the transformation of their country into a “theistically based polity” would put it on a slippery slope toward what Novak calls an “optimal theocratic polity,” one that might in fact eventually require “secular Jews to personally accept revealed law as normative in their own personal lives or that Jewish religious practices must be enforced in public”? There is, of course, Novak’s assurance that the creation of such a state must await the growth of “an overwhelming majority consensus” in its favor among Israel’s Jewish citizens, but he never fully explains why a smaller majority wouldn’t be sufficient. Nor does he seem particularly concerned about the rights of the, say, 7 or 17 percent of the dissenting population of such a polity.

While Novak’s main goal is to theologize the State of Israel’s foundations, he also strives to legitimize Zionism per se. The problem with secular Zionism, according to Novak, is that it rests so heavily on the Jews’ historical connection to the Land of Israel. But does “an ‘historic connection’ to a land,” he asks, “give a particular people the right to establish themselves there politically? Does ‘history’ grant or endow rights?” Even if it does (and Novak doesn’t seem to think so),

the “historic connection” of the Jewish people seems rather tenuous in the face of the Palestinian Arabs who make the same historical claim on the land, and it seems with much more history of living in the land on their side. So, if the Jewish people have a more cogent claim on the land, that claim should be the biblical one that pertains to the land of Israel alone, that is, it is because God chose this land for the Jewish people to settle there as permanently as is humanly possible.

This argument, of course, can only impress religious Jews and “those gentiles on their theological wavelength.” It will have absolutely no impact on the philosophical-theoretical adversaries of Zionism that the author of Zionism and Judaism seems to wish to refute, despite his readiness to consider the possible legitimacy, at some future date, of “a non-Jewish polity within the land of Israel” alongside the State of Israel.

Like David Novak, Chaim Gans challenges the notion that the Jews’ historical connection to the Land of Israel alone grants them the right to possess it. For Gans, however, this right does not originate in heaven either. In steering his way between the Zionists to the right of him and the post-Zionists to his left, Gans tries to show how the Jews’ historical connection to the Land of Israel gives them certain rights within it, but only when combined with other considerations. And these rights, he insists, do not override the legitimate, collective rights of the Palestinian Arabs in the same land.

Arguing against the religious as well as secular proponents of what he calls “proprietary Zionism,” in his new book A Political Theory for the Jewish People Gans quickly dismisses the idea that the Jews’ ancient ownership of the Land of Israel remains forever valid, even though it was occupied by others who had stolen it from them, or rather, stolen it from those who had stolen it from them. But if at the end of the 19th century the Jews could no longer be said to own the land, their ancient, long-standing, and newly intensified attachment to it endowed them with the right to be considered one of what Gans calls its “homeland groups.” The primacy of this territory in their history and identity gave them grounds for claiming self-

determination within its boundaries, despite what were at the time “its Arab character and inhabitants.” But what really sealed the Jews’ right to self-determination in their ancestral land was not their attachment to it but their bitter history outside of it, in Europe, above all, in the 19th and 20th centuries:

The Jews, thus, had a justification that can be called remedial—a justification based on the necessity to rescue themselves, and particularly their dignity—to realize their primary right to self-determination in their historical homeland, even if they were not actually present in it.

However, according to Gans, this right was limited, both with respect to scope of the territory in which it can be legitimately exercised and how it can be exercised within that territory:

If we agree that the necessity created by the persecution of the Jews is what tipped the case in favor of realizing their right to self-determination in the Land of Israel despite its being Arab demographically and culturally (or in favor of exempting them from responsibility for the wrongness of this act), then the territorial scope of their self-determination there cannot exceed the borders that were set when this necessity actually existed, that is, Israel’s borders as determined at the end of the 1940s.

Whether its creation was an act of remedial justice or, as Gans parenthetically suggests, a necessary evil, Israel has a right to exist, but only within specific borders. And even within these borders, the Jewish State has to uphold a limited right to national self-determination of the other homeland community in residence, the Arabs who did not leave when it was established. They, too, must enjoy autonomy in certain areas, such as education, and must be accorded “collective representation in the public sphere of Israel and its symbols.”

When Gans insists on the rights of all homeland (as opposed to immigrant) groups to a certain degree of self-determination, he is above all concerned with the individuals who constitute them. What is truly foundational for him, as a liberal, is peoples’ interest in living within the framework of their own culture, something which is vital to their well-being. Indeed, “most people desire also to ensure the continued existence of their particular culture,” which frames their lives and helps give them meaning.

Writing in Mosaic magazine, Peter Berkowitz has called what Gans labels “egalitarian Zionism” a “profound misunderstanding of liberal democracy.” Berkowitz argues that it is entirely proper for the majority in a liberal democratic state “to imbue political institutions and popular culture with its national spirit.” That majority has an obligation to extend individual rights, but not collective ones, to members of minorities. Therefore the authorization of “language, calendars, and anthems that reflect a majority’s culture and traditions is compatible with the equal protection of all citizens’ basic individual rights.” But Gans is not demanding that Israel relinquish its Jewish character. Nor does he argue that members of all minorities in Israel are entitled to collective rights that go beyond their basic individual rights. He agrees with those he calls “hierarchical Zionists” that a state can offer special benefits to the people with which it is identified, adding only that “since both Jews and Arabs in Israel are homeland groups, they should both, as a matter of principle, be granted hegemony vis-à-vis communities of immigrants but not vis-à-vis each other.” What Gans wants for the Arabs of Israel is, he says, something like what the francophones and First Nations have in Canada, where “[e]ach of them is self-governing and is able to live within the framework of its culture and preserve it for generations.”

Gans doesn’t go into great detail about the practical ramifications of his proposal, but he does make it clear that he considers “egalitarian Zionism” not only morally necessary but in the best interest of Israel’s Jews. Denying the Israeli Arabs their due only “nurtures the grounds for Arab antagonism and thus for Jewish fears.” Berkowitz disagrees, and warns that Gans’s proposal “is less likely to stabilize than to excite the very sectarian demands and passions that have impeded the incorporation of Arab Israelis into the common life of the country—and that are roiling Arab states throughout the Middle East.” Unfortunately, there is good reason to believe that both men’s fears are warranted.

If Gans’s egalitarian Zionism promises Israel’s Arabs only limited cultural autonomy, it holds out much more for Palestinians on the other side of the 1949 lines. Gans maintains that Israelis have no right to exercise control of these territories, since they arrived there only after they had already successfully established a state that allowed for their self-determination. But this sounds like philosophical fiat in the face of political argument. After all, those who disagree (at least those who do so on non-theological grounds) argue that, in the absence of a peace agreement that has yet to be obtained, Israel cannot simply cede the territories and maintain the safety and welfare of its citizens.

Unlike David Novak, Chaim Gans lets us know which post-Zionists he is arguing with and what they say. He divides them into three camps: “civic,” “post-colonial,” and “neodiasporic.” “Civic” post-Zionists, like Israeli sociologist Uri Ram, believe that Israel “should also stop regarding itself as the realization of the right to self-determination of its own Jewish population.” The state’s duty to be “neutral among all the ethnonational groups to which its citizens belong” supposedly requires this. But such neutrality, Gans argues, is altogether impossible. “[I]n a multiethnic and multinational state, the state cannot be neutral with regard to its citizens’ interests in adhering to their original languages and cultures.”

“Post-colonial” post-Zionists like Israeli academics Yehouda Shenhav and Yossi Yonah oppose Jewish self-determination in the Land of Israel “because they consider it a way of constructing an identity that facilitates the hegemony of Western Jews in Israel.” But even if their complaints about Israel’s treatment of non-Western Jews, Arabs, and other minorities are valid, Gans says, they do not justify their post-Zionist conclusion. For “[c]ompensatory multiculturalism for the communities of Mizrahi Jews, Arabs, ultra-Orthodox and immigrant workers in Israel can coexist with ethnonational self-determination of the Jews in Israel.”

Finally, “neodiasporic” post-Zionists like American academics Judith Butler and Daniel and Jonathan Boyarin and Israeli academic Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin are united in their belief that the “inexorable moral failure of Zionism” has made it necessary for the “[n]ationalist Jewish identity à la Zionism [. . .] to be replaced [. . .] with an individual and collective Jewish identity based on a reinterpretation of Judaism and Jewishness as predominantly diasporic.” This would entail the renewal of a Jewish ethos of “scholarship, antimachoism, delicateness [. . .] as opposed to the militarized and jingoistic ethos” of Zionism. Gans, for his part, is willing to acknowledge the value of many of these diasporic Jewish attributes, but doesn’t see why the Jews should be satisfied “with these alone.”

Zionism highlights the unwelcome aspects of Jewish homelessness and offers a remedy for the Jews’ utter dependence on the compassion of others. It points to the need for the reestablishment of a pervasive Jewish territorial culture to correct the diaspora predicament in which Jews had to restrict themselves to a narrow range of activities and occupations.

But this doesn’t preclude the Zionist ethos from embracing “the positive aspects of Jewish life in the diaspora.”

Gans’s comprehensive critique of post-Zionism is unfortunately marred, at one point, as Peter Berkowitz has observed, by his repetition of the discredited claim put forth by “the most extreme and reckless post-Zionists” that Israel was responsible for, as Gans puts it, the “atrocious expulsion of seven hundred thousand Palestinians” during its War of Independence. If Benny Morris’s research has by now made anything clear, it is that the number of Palestinians who were actually expelled was far smaller. The overall point Gans wishes to make, however, is that the wartime expulsion “can be acknowledged (and compensated for) without making it impossible to view Zionism as a movement that is on the whole just.”

Gans is a consistent thinker whose ultimate grounds for defending the Zionist enterprise require the support of Palestinian national rights, as he defines them. There is, however, good reason to fear the consequences of putting his ideas into practice. Those who do not find Gans’s understanding of the rights of “homeland groups” persuasive or are opposed to his proposals should show us where he has gone wrong and how to make a better case for the basic justice of the Zionist project—unless they think, like David Novak, that this cause can best be served not through recourse to philosophical-theoretical reasoning but by relying on God’s ancient promise.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Integralists and Us

A Jewish colleague once asked Harvard Law Professor Adrian Vermeule, “In a fully Catholic polity, the sort you would like to bring about, what would happen to me, a Jew”? “Nothing bad,” Vermeule replied. OK, let’s see.

Poets of the Tribe

The story of 12 Hebrew poets—in America.

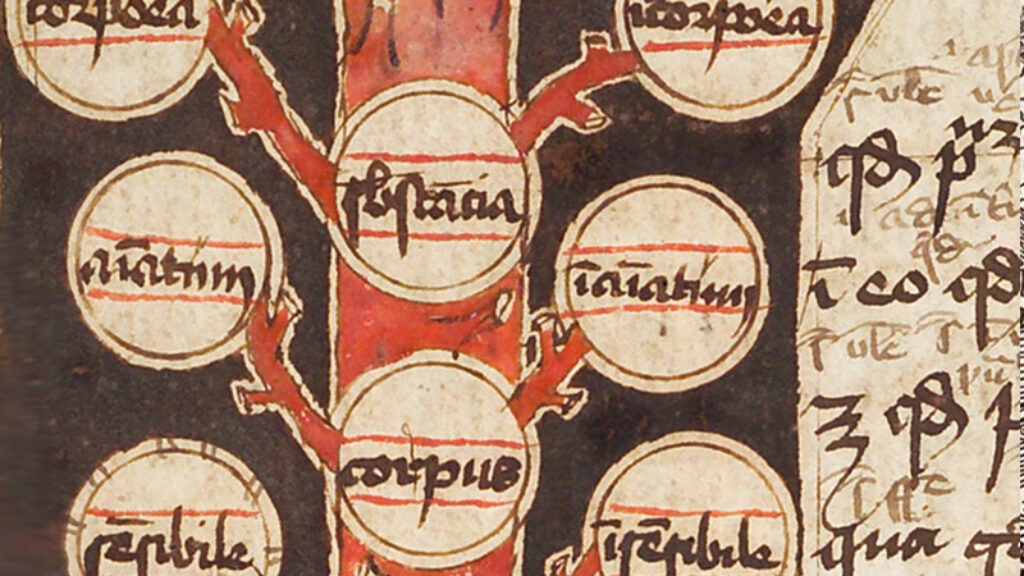

Roots in Heaven, Branches on Earth

Nothing sounds more idolatrous than drawing God. But that is just what a diverse bunch of medieval Jewish visionaries and scribblers set out to do.

National Socialism, World Jewry, and the History of Being: Heidegger’s Black Notebooks

The thinking reflected in Heidegger's recently published notebooks from the 1930s is alarmingly crude. It is also much more difficult to separate from his philosophy than many would like to think.

dee-kaye

There's nothing in Gans's writing to suggest he believes Israel must get out of the West Bank without an agreement. To insinuate otherwise, as the reviewer does, is misleading.

It's also inaccurate to say that Gans "doesn’t go into great detail about the practical ramifications of his proposal." Both in the current work, and his earlier Just Zionism, there is extensive discussion of practical issues.

Ariram

It is important to keep in mind that all the founders of the Zionist movement were secular Jews, motivated by nationalism not by religion. Their aim was the reestablishment of the nation-state of the Jewish people in the land of its origin. Not because God gave it to the Jews but because the Jews became a people there some 3500 y ago.

The Zionist movement was one of the most successful movements of national liberation in the 20th century. In all of written history there is no precedent of a people, who lost its territorial base for more than 1900 years, was dispersed all over the world, had no common language. In spite of all that it did not disappear from the world stage It was able to preserve its historical memory, its religion and its strong emotional attachment to the land of its origin. And then was able to reestablish its nation-state. If one adds to that the revival of the Hebrew language, dead for many centuries, and now a living vibrant tongue, used in all ways of life, one can understand the success of Zionism.

The founders who immigrated to Palestine during the Ottoman rule or during the British Mandate had a very strong emotional attachment to the land but it had nothing to do with religion and everything to do with nationalism.

Israel is ruled by a democratically elected parliament and not by a religious body. I hope that Novak’s goal to theologize the State of Israel foundations will never be realized.

Gans should be reminded that Eretz Israel (the Land of Istrael) was part of many empires but it was the an independent state of only one people - the Jews. The Zionist movement accepted the UN partition plan in 1947. That means that the Zionists agreed that two peoples live in Mandatory Palestine and that both have the right to self determination and independence.

Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people. Like many other nation-states, Israel has minorities. And just like in many other states there is discrimination against those minorities. Ask the Muslim communities in France and the UK, the Scandinavian countries and more. However, in Israel, one can explain some of that discrimination by the state of war in which Israel has found itself since its founding. In spite of that, from the beginning, Israel has strived to have equality for all, as written in its Declaration of Independence. Arabic is an official language in Israel. Israel acknowledged the collective rights of Arabs in the realm of education. Israeli Arabs thus have the right to educate their children is a separate framework, according to their own culture and language.

Contrary to Gans’ opinion many democratic nation-states do not believe that they have to shed their national ethnic identities in order to respect the civil, property and other basic human rights of their minority citizens. It is not antidemocratic for Israel to protect its status as a Jewish state in ways similar to those used by the French, Swiss, British, Germans, Italians, Lithuanians, Japanese and others to protect the status of their countries as national homelands. Israel should remain the nation-state of the Jewish people and should not became a bi-national state as proposed by Gans.

And Zionism was not a colonial movement. Not a single colonial movement,

European or otherwise, had any historical connection to the land it colonized. The English did not became a people in India or the French in Algeria. But, it is an undeniable historical fact that the Jews became a people in what later became known as Palestine, some 3500 y ago. And every colonial movement had a “mother country” behind it. There was no such entity behind the Jewish settlement in Palestine.

During the centuries there was always a Jewish presence in Palestine. Neither the Jews who came to Jerusalem in 1200, or the Jews who came to Safed in 1500, or the Jews who came in the 19th and 20th centuries are colonialists.