Poets of the Tribe

Alan Mintz has written a wonderful work of scholarship on a little-known subject: the large amount of serious and now-forgotten Hebrew poetry written in 20th-century America.

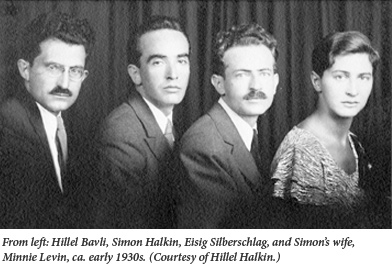

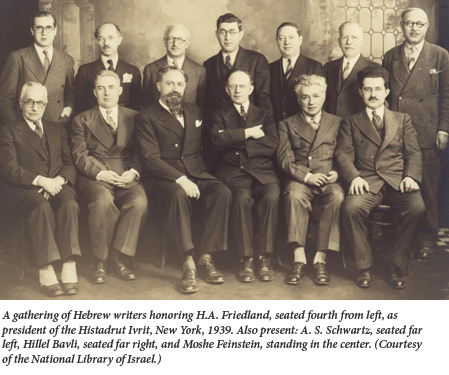

That, though, is a careless way of putting it. “Now-forgotten” means “once-paid-attention-to.” This was never the case with Hebrew poetry in America. The names of its leading practitioners—poets such as Benjamin Silkiner, A.S. Schwartz, Eisig Silberschlag, Ephraim Lisitzky, Israel Efros, Hillel Bavli, Shimon Ginzburg, Abraham Regelson, Simon Halkin, Moshe Feinstein, H.A. Friedland, and Gabriel Preil, to each of whom Mintz devotes a separate chapter of his book—were, by and large, no more recognized by their literate contemporaries than they are today. Known to a smattering of Hebrew readers in the United States and an even smaller number elsewhere, most of these men might as well have been writing in solitary confinement.

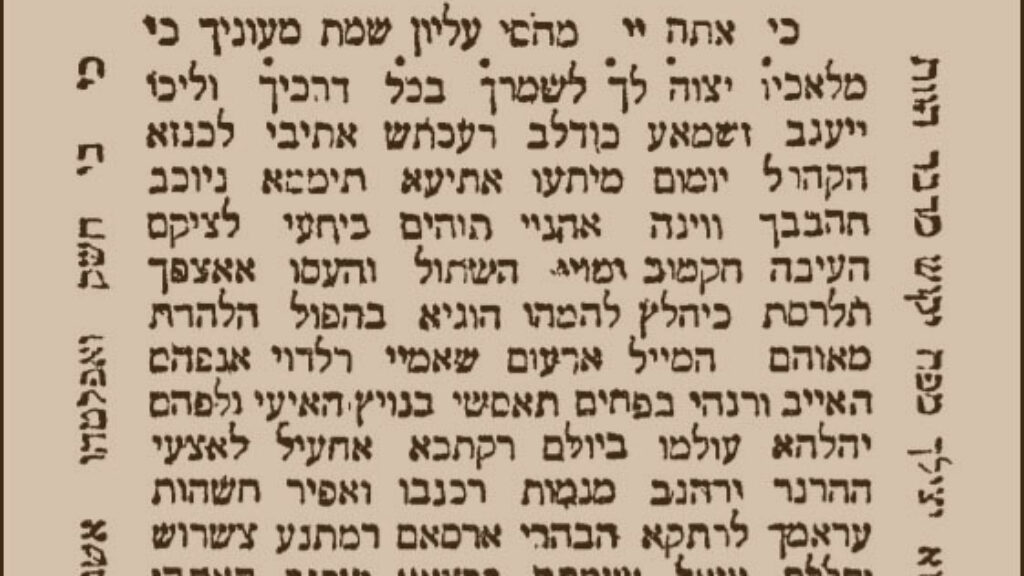

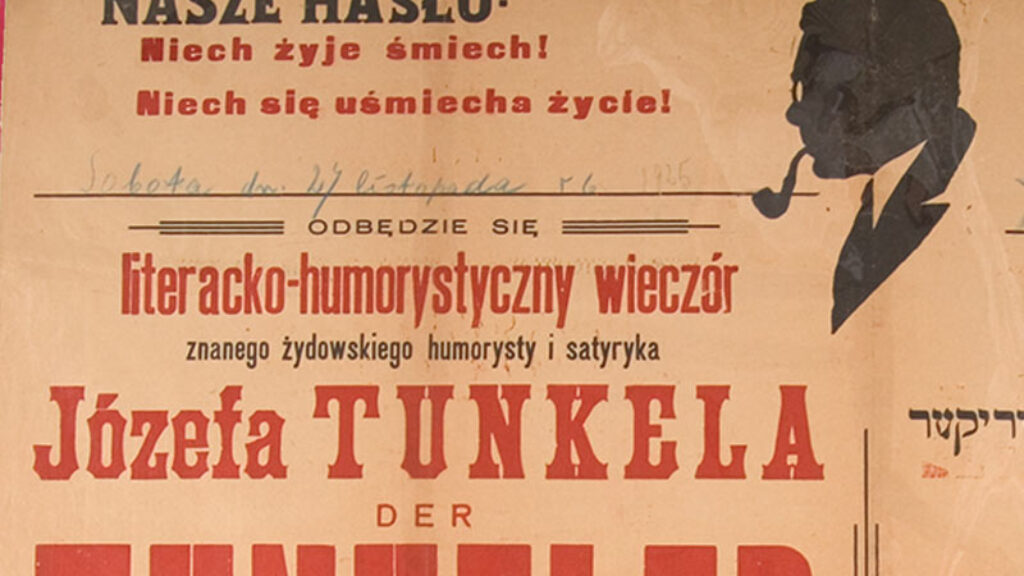

In his overall survey of American Hebrew poetry that forms the first section of Sanctuary in the Wilderness: A Critical Introduction to American Hebrew Poetry, Mintz, professor of Hebrew literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary, does an excellent job of explaining why these twelve poets and others like them insisted on writing in a language that few American Jews, let alone non-Jews, could read. The twelve shared much in common. All were born to traditionally religious parents in Eastern Europe, in the lands of the Tsarist empire, in the last years of the 19th century and first years of the 20th century. All received rigorous cheder educations that gave them an early knowledge of Hebrew and its classical biblical and rabbinic texts. Not a few had fathers or close relatives who were rabbinic scholars themselves and/or devoted readers of Hebrew literature. Some left Europe old enough to have studied in yeshivas and even to have published their first Hebrew efforts. All were products of the same elite cultural mold from which came a Berdyczewski, a Bialik, an Agnon, a Schneour, and practically every important modern Eastern European Hebrew writer. All turned to writing Hebrew the way their ancestors had, naturally, as the language that was, as Mintz puts it, “no more and no less than the very map of the [Jewish] nation’s being”—a language to which the only challenger at the time, anti-elitist and spoken by the Jewish masses, was Yiddish. (And practically every major late 19th-century and early 20th-century Yiddish writer, it must be said, started out in Hebrew, too.)

Most of Mintz’s twelve poets left for America with their families when they were in their teens. (Regelson alone was younger.) A few came later on their own, in their twenties. This age bracket, though Mintz does not dwell on it, is significant. Immigrants younger than ten or eleven rarely retain their foreign childhoods as a key component of identity; those much over thirty seldom incorporate the experience of their adopted country into their selves’ deepest levels. The early teens are a linguistic cut-off point, too; later than that, few immigrants learn to speak a new language without at least traces of a foreign accent. And by our early or mid-twenties, we have usually formed our basic opinions about the world and our relationship to it. Afterwards, even when these change, they change in terms of what they were.

Mintz’s poets were thus young enough upon arriving in America to Americanize more than superficially and old enough not to lose the Eastern European substrata of their personalities. How much their enterprise represented something indigenous to American Jewish life, then, and how much it was simply a spillover from Eastern Europe that ran strongly for a while in a deep but narrow channel and trickled out without leaving its mark, is a fair question. Mintz makes a cogent case for its essential American-ness. I am only partially convinced. But then, too, I am only partially convinced that it matters. Poetry is poetry before being anything else, and Mintz has performed an enormous service by introducing us to an unusual body of it (not all, to be sure, of equal quality) that now, because of his fine book, stands a better chance of being remembered.

Take, for example, Shimon Ginzburg, born in the Ukraine in 1890, who immigrated to the United States in 1910. Sometime in the 1930s, Ginzburg wrote a poem called “In Praise of the Hebraists in America.” Mintz’s translation of it, like all his translations in Sanctuary in the Wilderness (many of which—another great service!—appear together with the Hebrew text), is fluent and accurate without aspiring to be poetry itself. It begins:

Like a sparse string of lights, scattered but connected,

belonging to a strange and darkly snowy train station

that suddenly pops up among the winter fields,

forgotten somewhere between New York and Cleveland,

I have imagined you, Hebraists in the expanses of America.

No one knows who planted your seed, a holy seed, here in this land

or who is the lost father and the lost mother who left you

on your own here in this winter night of snow and stars.

. . .

the Potomac River will give heed to you and the Mississippi will look on astonished:

For passing before them is something surpassingly handsome

and sad and exalted,

which has no match and will remain unique forever.

The snowy fields of Pennsylvania or Ohio; the train cutting a trail through the white night; the little lit-up station appearing and vanishing in a vast land planted with the “holy seed” of Hebrew; the bardic invocation, in biblical inflections, of American cities and rivers—Ginzburg’s far-flung Hebraists (he was on his way to Cleveland on the invitation of H.A. Friedland, who had established a Hebrew teachers’ institute there) are cast as authentic American pioneers, the westward-bound sowers of a sacred, three-thousand-year-old tongue in the soil of the prairie.

But the poem soon reverses itself. Somewhere in the “expanse of America,” the poet imagines as he stares out the train window into the darkness, is a “Yankee shopkeeper” named John, smoking his pipe while listening to the news on the radio, which briefly broadcasts the “bark of Hitler” from a speech of the Fuehrer. John listens dreamily to a language he cannot understand while calmly puffing smoke at the ceiling, and the poet continues:

But you, alike men of action and princes of dreams,

John’s complacency is not for you,

and not for you either is the frozen majesty of these fields

or the Lord of the Forest’s great wintry tranquility.

Every day and every night, whether at work or leisure,

The horrid curse of Exile and the cry of your brethren from the corners of the earth mortally wound you.

Suddenly all has changed. No longer a latter-day American frontiersman, the Hebrew poet, carrying with him the anguish of European Jewry and the “horrid curse” of Jewish homelessness, is now a foreigner in an immense continent with whose natives he has nothing in common. This shift of consciousness has not been forced on him from without. The pipe-smoking shopkeeper has risen spontaneously from his own habitual patterns of thought.

As poetry, “In Praise of the Hebraists in America” starts out better than it ends, and Ginzburg, as Mintz observes, had a “righteous disdain” for American life that was not necessarily shared by other American Hebrew poets. Yet in the same paragraph, Mintz acknowledges that while “most [of these poets] found [in America] something to love, or at least be fascinated by,” the fact remains that “none of the American Hebrew poets ever felt truly at home in America.”

And how, really, could they have? They spoke an English that betrayed their foreign origins. They had chosen to be incomprehensible to their fellow countrymen, even to their fellow immigrants. The Hebrew literature they belonged to had its creative centers far away, in Odessa and Berlin, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. (All of the twelve were Zionists, in part because the future of Hebrew and Hebrew literature was closely linked to the future of the Hebrew-speaking Palestinian Yishuv.) The jobs of Hebrew teachers and educators that most of them worked at produced frustratingly disappointing results and did not bring them into daily contact with ordinary Americans. When they opened a newspaper, their eyes sought out the news from Europe and Palestine, not from New York or Washington. And as this news grew progressively grimmer in the years leading up to World War II, they felt, like Ginzburg, increasingly remote from an American public that yawned and turned to the sports pages.

And yet, as Mintz argues, they also were American. They went to American high schools, received their degrees from American colleges and universities, were immersed in English and American literature, traveled widely in the United States, knew it better than did most American Jews who were concentrated in the large cities of the East Coast. (Not only Friedland left for the hinterland. Lisitzky was a Hebrew educator in New Orleans. Efros taught for many years in Buffalo. So did Bavli, who then found work in small-town Connecticut. Ginzburg crisscrossed America, raising money for Hebrew cultural institutions in Palestine. Regelson joined Friedland for several years in Cleveland. Halkin had his wanderjahren that took him as far as California. Silberschlag spent his later years at the University of Texas. Preil lived for a while in rural Maine.) And they were, in their poetry, intensely engaged with America: curious about it, excited by it, desirous of embracing it, eager to connect with its history. One of the most extraordinary things about them, the subject of yet another long section in Sanctuary in the Wilderness, was their use of Hebrew as a medium for exploring and retelling New World myths and sagas.

Consider: Silkiner, in 1910, publishes a 1,500-line narrative called “Facing the Tents of Temurah” about the tragic encounter between an Indian tribe and Spanish conquistadors. In 1924 appears Bavli’s “Mrs. Woods,” a verse monologue by a 92-year-old, blue-blooded American farming woman. Efros, in 1933, comes out with “Silent Wigwams,” a lengthy poem telling the tale of a 17th-century American Indian woman belonging to the Nanticokes, a tribe living on Chesapeake Bay, and the runaway from an English colony who becomes her lover. That same year sees Lisitzky’s “Dying Campfires,” its 320 double-columned pages a chronicle of two tribes, the Children of the Serpent and the Children of the Viper, with a cast of characters including Nanpiwati, the Serpent chief’s son, Namissah the Star Maiden, their daughter Genetaskah, and the Viper chief’s son Midaingah. In 1942, Efros is back with “Gold,” a multi-chaptered story about the beautiful Lola Logan and the proudly ambitious Ezra Lunt, who meet in the Gold Rush. And in 1953, Lisitzky returns with “In the Tents of Cush,” a medley of re-invented black spirituals, folk songs, and fiery church sermons.

All in Hebrew! Mintz gives several good explanations of this rather startling phenomenon. (No Hebrew poet in Eastern Europe, certainly, ever wrote a heroic account of the long struggle between Poland-Lithuania and the Teutonic Knights, or set a love story in an epic about Kievan Rus and its devastation by the Mongols.) There was the great influence of Longfellow, still highly popular in the American Hebrew poets’ youth, with his epics like Evangeline, The Song of Hiawatha, and The Courtship of Miles Standish, all set in America’s early years. There were the biblically-minded Pilgrim fathers and the new Canaan they sought to found, highly appealing to writers raised on the Hebrew Bible since infancy—and highly flattering, too, for if America was a biblical enterprise, was it not also in some sense a Jewish one? There was, conversely, an identification with the American Indian, dispossessed of his land as the Jews had been dispossessed of theirs. There was the desire to write a distinctly American Hebrew poetry, different from all other Hebrew verse, thereby demonstrating to the world of Hebrew letters what uniquely grand vistas the American Hebrew poet could unveil. And there was the desire to possess America (intimately, knowledgeably, from within) by means of its own stories about itself—and to do so in Hebrew.

It’s fascinating stuff. But is it good poetry? Here Mintz forces me to disagree with him. Though aware of its faults, he finds much of it on a high level. I don’t. Here, for instance, are some of the liveliest lines from the first chapter of Efros’ “Gold,” which Mintz takes to be “one of the masterworks of American Hebrew literature.”

Huddled together they [Lola and Ezra] sat,

While from deep in their souls rose the days

Of wilderness, prairies, and mines,

Each day a world in itself,

Each with its sorrow and anguish,

Each now revealed to have been but the merest of foreshows,

Humbly aware it was needed,

Passing before them and fading.

“Catch me, Ezra!” Away over the mountains

She flew in widening circles with him on her heels,

Until in a valley she vanished,

Leaving him standing there, baffled.

“Catch me, Ezra!” Lunt saw her and sprang,

Flying after her in great circles,

Arms held out. Each time he thought they would touch

Her wild hair, she slipped away sideways

Into another ravine until, unespied,

She landed right in his arms.

The problem is not the translation, which is mine and does aspire to be poetic. It’s the rhetorical nature of the original. Mintz is good at expounding on the stylistics of his poets. Brought up on the Hebrew classics and cut off, for the most part, from the great changes taking place in the Hebrew of Palestinian speech, the Americans tended to write a Hebrew that was rich, dense, and grammatically intricate, but also conservative and sometimes even archaic—a tendency less damaging in the internal speech of the short lyric than in long narrative verse, with its mimesis of human dialogue and action. Efros is far from the worst offender in this respect, being one of the American Hebrew poets who tried most to modernize and simplify his language. Yet the language of “Gold” is on the whole closer to the Eastern European Hebrew of a 19th-century narrative poet like Y.L. Gordon than, say, to the Hebrew narratives that Natan Alterman was writing in Palestine in the 1940s.

And even weaker than the language is the visualization of the scene—the false visualization, since no woman has ever been chased by a man as Ezra chases Lola, over hill and dale, since the days of Daphne and Apollo. Efros fails in “Gold” to think himself imaginatively into his characters and their world—and this is the case, as far as I can judge, with the entire genre that Silkiner launched. It doesn’t ring true. It’s off-tune. (That one could be on-tune in a historical narrative about America written in a Jewish language is demonstrated by I.J. Schwartz’s highly readable Yiddish verse novel Kentucky.) It represents Hebrew’s attempt to go native by shortcut, to take America by force, to domesticate itself in an American landscape on which it was, inescapably, an intruder. Ginzburg’s “In Praise of the Hebraists in America” is more genuine precisely because it acknowledges this intrusion. Its Hebrew poet strikes a grand Whitmanesque pose—and recoils from its bravado.

The best American Hebrew poetry written about America, I think, always has this double perspective. An excellent example in Mintz’s book is Gabriel Preil’s “Small Wreathe of Poems for Abijah,” a sequence written, as Preil stated in a footnote to it, “in a house built in 1824 in Putnam Valley in New York State by a pious Christian and lover of the Bible, Abijah Lee.” Its opening stanza (in my translation) goes:

Here the years appear not to have passed.

As ever, the lark sings between valley and mountain.

When Lincoln was a long-legged boy, tingling with a fine sadness,

And stars like sky-grown apples shone on the apple pickers,

You built a house . . .

Now—you still walk in it,

You, named for a king of Judah, his dark eyes whispering coals,

You, a New Englander, your blue eyes fitly set.

As Mintz—who misses next to nothing in the many poems he comments on—points out, the Hebrew for “fitly set,” yoshvot al mileyt, comes from the Song of Songs, reinforcing the biblical analogy. The poet feels comfortable in this house, to whose first occupant he can say, “You watered your flocks every morning, reaped and garnered each day Scripture’s fields’ trusty crop.” Gradually, however, in the course of the poem, the bridge built between the 19th-century New York farmer and the 20th-century Lithuanian-born Jewish poet collapses, and Preil’s last lines, reminiscent of Ginzburg’s in “In Praise of the Hebraists of America,” are:

You came so close to my people’s bubbling fount,

Knelt to slake your thirst at its lips.

But your kinfolk have smashed, in my day, every jug,

Sown scorched wastes, icy-hearted.

Simon Halkin, another of the best poets among Mintz’s twelve, wrote a sonnet sequence, “On Michigan’s Dunes,” that pivots on a similar dual consciousness, which keeps dragging the poet back from the pristine beauty of the shores of Lake Michigan to the fate of Europe’s Jews. His “Scenes from Nova Scotia” works similarly; so do other American Hebrew poems. And Halkin has a poem called “To the Negress,” its contents even more politically incorrect today than its title, in which eyes like Abijah Lee’s stand for all that is alien to the Hebrew poet in America. Describing a fleshy and erotically arousing black woman he is sitting next to on a New York bus or subway, smelling of perfume and wearing a tight-fitting, department-store dress that cramps her ample body, the poet rhapsodizes: “Up, jungle woman, off with your corseting silks! Animal-muscled, let your brawny thigh gleam / And strike with its ebony sheen turbid, blue northern eyes blind.” Like the woman, he, too, the Hebrew poet, with his “ancient patrimony” of “smoldering desert heat,” is a prisoner in a land of frost, a “blue-eyed Not-mine.” The two of them, he proposes, should get drunk and “dance the town mad” until they bring its skyscrapers crashing down on the “hard, cold, blue-eyed ones / Who have carried you off and carried me off just like you / Until, captive, we forgot all we knew beneath the bright eye of the sun.”

Here, the double movement of consciousness expresses the sense of strangeness in America through an identification with something uniquely (and to the Eastern European immigrant, exotically) American-the dark-skinned descendants of African slaves, fantasized as primitively passionate and awkwardly out of place in a stiff and repressed white society. Blacks were sometimes cast in this role by Yiddish poetry too, as they were by American Jewish literature in English. But though “To the Negress” has no more to do with outer reality than does “Gold” or “Facing the Tents of Temurah” (Halkin, a timid man, would, fortunately, never have dared approach a real black woman with such talk), it is truer on a fantasy level than they are. The Hebrew poet was out-of-place in America. Cut off from both his patrician base in Eastern Europe and the Hebrew-speaking streets of Palestine, he had little to connect to or to nurture him. As Zalman Shazar, Israel’s third president, sensitively wrote in a 1949 introduction to the collected poems of A.S. Schwartz, quoted by Mintz, there was in the American Hebrew poets “something of the self-gratification that proud artists allow themselves, something of the feeling of superiority enjoyed by monks offering obeisance to a Hebrew princess and serving her with no expectation of reward either in this world or in the world to come, either in the Diaspora or in the Land of Israel.”

Simon Halkin was my uncle. A.S. Schwartz was the grandfather of Jonathan Schwartz, a second cousin and my best friend in my elementary school years. Moshe Feinstein founded the Herzliah Hebrew Academy in New York, of which he was the principal; after leaving a Jewish day school for a public high school, I took classes there for a while and played stickball in the street outside the building. Hillel Bavli was a friend and academic colleague of my father’s and was often in our home with his small son and tall, thin, dreamy wife Rahela, an ex-shepherdess from Palestine who continued, so it seemed, to miss her sheep. The Efroses, Israel and Mildred, were occasional visitors, too. “Millie” Efros was a former southern belle and still had the lilt and charm of one. I liked both women.

Although I simply took it all for granted as a child, I grew up at the epicenter of the world of American Hebrew culture that Mintz portrays. I was sent to a New York kindergarten named Bet ha-Yeled, “The Children’s House,” where I learned to say “gamarti,” “I’m finished,” when I was done with my morning snack. For six years, I went to a Hebrew-speaking summer camp called Massad where we played baseball, fought color wars, and spoke to our counselors (though not, if we could help it, to each other) in Hebrew. Some of my parents’ friends raised their children in Hebrew; once-I don’t remember exactly how old I was-my father and I decided to speak it at home too, but my mother and sister refused to go along and the experiment failed. Every week Ha-doar, the literary and cultural journal of American Hebraists, arrived in the mail. I read my first Hebrew novel, a translation of a popular Yugoslavian children’s story about a world-cup-winning soccer team composed of eleven brothers, well before my bar mitzvah.

This was the environment in which I grew up, but it took Sanctuary in the Wilderness to place it in full context for me and make me realize the scope of the project of which it was part. Mintz’s book, besides being a superb study of individual American Hebrew poets, offers a valuable history of the American Hebrew cultural movement as a whole. From it I learned how, spreading out across the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, men like Friedland, Lisitzky, and Efros, backed by others like Silkiner and Feinstein in New York and Silberschlag in Boston, created a network of Hebrew afternoon and evening schools, Hebrew teachers’ colleges, Hebrew periodicals, and Hebrew literary and discussion groups that were participated in by tens of thousands of American Jews. Much of this took place in the American interior-especially the Midwest, in cities such as Cleveland, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Detroit-and went hand-in-hand with vigorous Zionist activity. Indeed, as Mintz explains, precisely their being Jewish backwaters made such places promising locations for capable Hebrew educators, not all of them poets and writers, who took advantage of the Jewish cultural vacuum they found there to fill it with Hebrew content.

Looking back on all this today, it seems impressive, even heroic. And yet one wonders to what extent Jewish education in America was ever really, as Mintz puts it, “captured by the Hebraists,” and how much actual influence, even in their heyday in the years before, during, and right after World War II, the Hebraists had. Certainly, when one compares the Hebrew movement in America with its counterpart in Eastern Europe in the same period, its successes were minimal. In Poland, in the years between the two world wars, hundreds of thousands of pupils passed through the ivrit be-ivrit schools of the Tarbut system, in which they studied all subjects in Hebrew and came out speaking it fluently. Nothing similar ever existed in America, where, in a pre-Jewish-day-school era, Hebrew education was strictly supplementary, taking place after public school had ended for the day. The Midwest may have been a bastion of it, but the boys at Massad whom we Easterners called by names like “Kansas City,” “Des Moines,” and “Omaha” after their singular places of origin knew even less Hebrew than most of us did-which was, on the whole, not much.

You can’t compare America to Poland, you say. No, you can’t. Large numbers of Polish Jews needed Hebrew, not just to express something important in themselves, and not just because they didn’t feel part of Poland, a country in which they knew they had no future, but also because they looked forward to a life in Jewish Palestine and were preparing for it. American Jews did not need Hebrew, or at least never thought that they did. They were Americans whose future was in English. They were willing to pay the tuition to send their children to Hebrew school for a few hours a week, especially if the school was a good one without worthy competitors, but what was learned there was of no great consequence to most of them or most of their children. Perhaps, for a while in the United States, the figures-number of children enrolled, percentage of hours devoted to Hebrew, etc.-looked good. But figures don’t read poetry. After attending such schools, American-born Jews were incapable of understanding a Hebrew far simpler than that of the American Hebrew poets. The poets knew that. They had taught those Jews themselves.

Cynthia Ozick, too, had an uncle, Abraham Regelson, who is one of Mintz’s twelve poets. In a review of Sanctuary in the Wilderness in The New Republic, she writes about him and his relationship with my uncle. The two met as boys at Morris High School in the Bronx, became close friends, “conversed in Hebrew, and fell into passionate discussions of poetry and philosophy,” read and admired each other’s Hebrew poetry, and went on to study together at City College. Later, in the 1930s, each also attempted to settle in Palestine (each returned to America and re-settled in Israel after the establishment of the state); yet long before this, the two had “a bitter falling out.” Ozick writes that she was told by her cousin, Regelson’s daughter, that “the break erupted out of a volcanic charge of literary theft: Halkin accusing Regelson of plagiarism, Regelson accusing Halkin of plagiarism, each once again the double of the other. Mutual recrimination, smoldering, became mutual contempt.”

What was thought to have been plagiarized, Regelson’s daughter didn’t say. I don’t remember my Uncle Simon, whom I knew well, ever talking about it. Still, I’m willing to guess. It couldn’t have been a specific poem. The two men’s poetic styles were too different for a poem by one of them to have been mistaken for a poem by the other. It must have been an idea; in all likelihood, a big idea. And such an idea is easily identifiable. It is an idea about God. It is one that Halkin and Regelson often wove into their poems-the idea of God as a primordial unity dismembered into infinite fragments in the material world, each tormented by its apartness from the others, each crying out for the others, each yearning to be re-united with the others, each striving to be recognized by human consciousness, which alone can bring about the reunion. Halkin and Regelson’s God is a suffering one, though not in the Christian sense, who needs mankind’s compassion and understanding more than mankind can hope for His.

If I’m right, both men were innocent. It’s possible, even probable, that they talked about these things in the days when they were friends; Halkin said this, Regelson said that; in the end, each accused the other of stealing his thoughts. But neither need have stolen anything. Both were drawing, as Mintz writes in his discussions of them, on imagery in Lurianic Kabbalah and Chabad Hasidism that was available to any Jew familiar with these traditions. Halkin put his stamp on them, Regelson his. Both men were non-practicing Jews phenomenally steeped in Jewish sources. Both knew their Blake and their Shelley, their Whitehead and their Bergson, as well as their Kitvei ha-Ari and their Tanya. Both were non-believers with a deep craving for religious belief.

Both were carrying on the Eastern European Jewish heritage. The psychological and spiritual crisis caused by the loss of religious faith in adolescence or early adulthood (written about by Mintz in an earlier book, Banished from Their Father’s Table) is a major motif-the major motif, one might say-of late 19th-and early 20th-century Eastern European Hebrew literature. In Hebrew author after author-Lilienblum, Feierberg, Bialik, Berdyczewski, Gnessin, Brenner, and others-it played a role that it seldom did in the Yiddish and American literature of the age. (To find something akin to it in English, one has to turn to Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.) It characterized an entire Hebrew-writing elite who, brought up on the templates of rabbinic Judaism, saw these smashed by modern critical and scientific thought, and longed for their vanished wholeness and harmony.

To one degree or another, most of Mintz’s other poets-Lisitzky, Schwartz, Efros, Bavli, Feinstein, Silberschlag, Preil-shared this longing, too. They brought it with them to America’s shores. It shaped their experience of America. They loved America in their way, but what they loved most in it was not its freedom, or its democratic society, or its human optimism, or its technological innovativeness, but its natural grandeur-“that great ungraspable kingdom,” as Preil called it, “[that is] all divine signification, all untouchable golden mystery”-the vast physical spaces of the American continent with their secret glades and valleys, their lonely lakes and silent forests, that would have been the perfect places for God to hide if God were still hiding anywhere. If only America could have spoken Hebrew back to them when they spoke Hebrew to it! Then it might have told them where to look.

“Will more Hebrew literature be written in the United States?” Mintz asks in a meditative Afterword on the future of Hebrew in America. “Will new writers arise to continue the tradition described in this volume? It does not seem likely, but no possibility should be foreclosed.” No, it does not seem likely. What came to an end with the end of Hebrew poetry in America, formally datable to the death of Gabriel Preil in 1993, was not just a literary movement. It was a long history of Hebrew as the international language of the Jewish people, of which American Hebrew poetry was part of the last, expiring wave. Today, when there are more Hebrew speakers in Israel than there were in the days of the Bible, Israeli and American Jews speak to each other in English. So do Jews from everywhere. English has become the language of Jewish global communication, of Jewish organizational life, of Jewish conferences, of Jewish scholarship and literature outside of Israel. It is the language of Sanctuary in the Wilderness. It is what America answered its Hebrew poets in.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Rov in a Time of Cholera

From limiting minyan sizes to magical amulets, a look at how one rabbi faced waves of cholera epidemics over his long 19th-century career.

Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

What are the conditions for a Jewish intellectual renaissance? Disagreement is one, inconsistency might be another; look at the early Zionists.

Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

“Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos” and decided to try to make it in Warsaw. A Yiddish satire, translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

“Repent, Repent”

In his new book, How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture, David A. Lambert argues that repentance, as we understand it today, is absent from the Hebrew Bible.

marcus moseley

The Hebrew poetry cannot stand up to the contemporary Yiddish poetry of the period, by and large.

But some of the prose: Lissitzk's Elleh toldot adam; the publicistic word Ravidowitz; literary criticism in particular--Shimon Halkin's 'ad masher, Grodzensky, Bavli---etc...was amazing.

My own favorite is Shimon Halkin's "Yaa'kov Rabinovitz beYarmut"--riveting, so funny, so true--I adore this poem.

mm