The Adjectival Liberal and The Kingship of God

History didn’t end after the fall of the Soviet Union, but liberal democracy did emerge triumphant. Whether borne by Bill Clinton’s “third-way” neoliberalism, George W. Bush’s neoconservative internationalism, or Barack Obama’s hopeful pragmatism, liberalism was the West’s permanent governing philosophy. Or so it seemed. Liberalism is everywhere under siege now. Its critics claim that it deprives us of real community and meaning; it isolates and deracinates us; it turns us into lonely, nihilistic consumers who think we are emancipated but are really just gratifying our own base desires, or the ones

created for us by the neoliberal economy. Alternative political theories—often centered on ethno-nationalism, religious fundamentalism, or both—seem newly plausible. How should liberals respond?

Michael Walzer’s proposal in his thought-provoking and beautifully written new book is to defend liberalism not as an “ism” but as an “adjective,” a way of being. Liberalism, he writes, is often thought of as an “encompassing ideology,” founded in a theory of natural rights, the social contract, or utilitarianism. As such, it implies certain ideas about how humans flourish: as rights-bearing individuals in a pluralist society. This “ism” liberalism seems to demand that we adopt a particular way of thinking, or set of goals, or identity. Walzer’s adjectival liberalism, by contrast, “determines not who we are but how we are who we are—how we enact our ideological commitments.”

Being a liberal, in other words, is about the means of politics, not, for the most part, its ends. Of course, the liberal adjective can’t modify every political orientation; there can’t be liberal racists, or fascists, or theocrats, since the ends they aim at would undermine liberal democracy, but there should be no liberal catechism. Adjectival liberals, Walzer emphasizes, can have strong, even radical commitments, but they refuse to actualize those commitments on the backs of prostrate foes. Or as he puts it more pointedly: “There have been too many murdered bodies.” We can disagree, even vehemently, about what we want and believe; we can, and indeed should, push to make real changes in the world; yet we can still treat one another as human beings possessing dignity and worthy of respect. Politics is permanent. It can also be “better”: a competition between partisan rivals, not a civil war between enemies and friends.

This is a deeply decent, humane, and hopeful vision. It also fits squarely with what we have come to expect from Walzer, who is one of the towering political theorists of the past century. During his seven decades of public writing, he has strongly influenced not only debates but entire fields, among them the history of European political thought, just war theory, democratic theory, and Jewish political thought. As the longtime editor of Dissent, he also helped shape leftist discourse with moral clarity and humility, supporting its intramural critics and refusing to follow its fashions—from Stalinist apologetics to uniform opposition to the Iraq War—even at the risk of facing intellectual vituperation.

He has also been willing to admit to being wrong. At one point in The Struggle for a Decent Politics, Walzer describes the attitude that academics should nurture in students: “Join the argument; don’t try to repress it.” This could be a motto for Walzer’s entire remarkable career.

The adjective “liberal” can qualify both institutions and people, but Walzer’s argument is strongest when applied to institutions. Take democracy. Classically, this meant “rule of the people.” The ability to speak for the people is claimed by the majority, but majority rule is clearly insufficient for democracy. We also have to ask: Who is included in “the people”? Who gets to determine the majority? In ancient Athens, it was a small cadre of citizens who ruled over a much larger number of women, foreigners, and slaves. In America, workers, Blacks, ethnic and religious minorities, and new immigrants were all once excluded from “the people.” To earn the adjective “liberal,” a democracy has to include all classes of people. And that’s not all. Genuinely liberal democracies set limits on what laws any government can make, often by codifying them in a written constitution or binding legal precedent. Such limits can be changed—constitutions can be amended, precedents overturned. But these changes must be pursued slowly and with broad consensus. No simple majority can do away with civil and minority rights, eliminate competitive elections, or neuter the courts. As Walzer concisely summarizes the point: “A liberal democratic state is designed to prevent state officials from violating the rights of individuals in the name of majority rule.”

Liberal democracies are also pluralistic. This means, to begin with, that politics is an arena of multiple and competing parties. Contra Marxists and fascists, there is not—nor will there ever be—a single unifying identity that can organize a polity (the proletariat, the volk). Human interests and values are manifold, not monistic. And that’s a good thing. Walzer is at his most lyrical when describing the “wonderfully lively civil society, densely and diversely populated,” not only with political parties and pressure groups but social and religious movements, schools, mutual aid societies, charities, sports teams, and more. We find our friends and partners in these places. They make us who we are.

The adjective “liberal” underwrites pluralism in two ways. First, it makes membership voluntary. No one is born into a bowling league. More important, the right to leave extends even to memberships one was born into, like religious faith. Liberalism’s permission to shed our inherited selves if we choose has been a frequent target for critics—from philosophers like Michael Sandel to current right-nationalists and religious “integralists”—who blame it for the alienation of modern society. In practice, though, most people end up living and praying like their parents. Regardless, we should be careful not to ask too much of liberalism. “What the adjective ‘liberal’ most importantly guarantees,” Walzer writes, “is the freedom, the openness, of civil society.” It does not promise us meaning.

Where we do find meaning is in our associations. And here things get trickier for Walzer. Liberals value skepticism, irony, and pluralism. Yet humanity’s very diversity means that people are going to believe and practice things that challenge this ethos—and they may do so entirely unironically, with very little patience for other points of view. Consider national identity. One might frame it as an either-or prop-osition: prioritize your fellow citizens, as nationalists argue, or value all human beings equally, as cosmopolitans (and often liberals) do. Walzer, with characteristic moral nuance, rejects this dichotomy. We need to meet people where they are: “some people mean more to me, require more of me, than others. . . . Collectives, like nation-states, can also be obligated to some people more than to others.” We should also push people to be better: “Liberals would add . . . universal obligations to their particular obligations. It is the combination that justifies the adjective.”

Or take gender inequality. As a feminist, Walzer is highly critical of traditional religions, which are often led by men, exclude women from the clergy, and mandate gendered forms of religious expression. One increasingly common response among political philosophers is to press for state intervention. Such groups should, perhaps, be allowed to exist. But they should be actively discouraged—publicly chastised, denied tax credits, refused special treatment—until they repent and change their ways. Admirably, Walzer rejects this heavy-handed approach. Adjectival liberals should support pluralism even when it’s hard, and they should also respect the agency of religious women themselves: “Only illiberal feminists would argue that there is only one way. The state should certainly not be enlisted as a defender of singularity.”

The basic contours of this dilemma have actually been with liberalism since its inception, when the antagonists were not feminists and traditionalists but Catholics and Protestants. If people are going to be free, they should be able to have deeply held commitments, religious and otherwise. But people who think they’re right usually want others to think so too. And to convert them, they’ve often been willing to do whatever it takes, from coercion to terror to holy war. Liberalism’s ingenious solution was to compartmentalize human life—to divide society into different spheres and erect walls between them. As John Locke wrote in his Letter Concerning Toleration, “I esteem it above all things necessary to distinguish exactly the Business of Civil Government from that of Religion.”

Such distinctions have enabled liberal freedom and civil society. I don’t need the DMV clerk to believe in my God; he just has to renew my license. My neighbor and I don’t ask each other how we voted, but we do borrow sugar from each other and keep an eye on each other’s kids. “How do we know what lies deep within?” Walzer asks rhetorically. “Liberals don’t go looking.” This is not to say that liberalism rejects activism or community, as its critics often charge. It’s that, as Alexis de Tocqueville so brilliantly illustrated in Democracy in America, liberals find solidarity mostly in voluntary associations.

We are free because we can choose to live out large portions of our lives as we see fit. We might join groups that toe the liberal line. But we might also affiliate with those that are questionably liberal, ornonliberal, or actually illiberal. The woman standing behind me at the checkout spent her Sunday at a traditional Latin mass; the man in front of me spent his intercepting whaleboats for Greenpeace. We’re all waiting in the same line. How should we treat each other? Now the question isn’t how a state, or a political party, or an association earns the adjective; it’s how you or I do. To which the liberal answers: respect and tolerate one another, affirm shared political principles of free and equal citizenship, and stand nicely on life’s lines. If we do all that, how and with whom we choose to affiliate on our own time is up to us. Liberal freedom requires something more than indifference but something less than zealotry. We can have strong beliefs and act on them, but we should also respect society’s roles and divisions. Insofar as we do, we can be adjectival liberals.

Or that is what I expected Walzer to conclude when he opened the book this way:

Today, I think, liberals like us are best described in moral rather than political or cultural terms: we are, or we aspire to be, open-minded, generous, and tolerant. We are able to live with ambiguity; we are ready for arguments that we don’t feel we have to win. Whatever our ideology, whatever our religion, we are not dogmatic; we are not fanatics.

This sounds like a broad “we,” which can shelter all sorts. “Let there be many communities!” Walzer declares with emphasis. “I can be, all at once, a Jew, a socialist, a Dissent-nik, an academic political theorist, a New Yorker, an active (but part-time) citizen of the American republic.” But on closer inspection, Walzer’s version of the liberal ethos turns out to be considerably more restrictive. Some of this follows logically. Liberals, plainly, can’t abide those who want to abolish liberal politics, from the left or the right; toleration can’t extend to self-destruction. The issue is that Walzer doesn’t stop at our political beliefs and practices. He wants to know how we spend our off-hours. And if we want to earn the adjective, it turns out, there are certain things we can’t do or think.

The things with which Walzer is most concerned in this regard are religious. He passionately affirms that we can all still be radicals in our political commitments—with one conspicuous exception:

Democrats are radically opposed to all tyrannical, hierarchical, and oligarchic regimes. . . . Socialists are radically opposed to capitalism. . . . Nationalists are radically opposed to imperialism. . . . Communitarians are radically critical of a society of self-regarding individuals. . . . Feminists are radically critical of the subordination of women.

Religious groups, however, occupy their own special category: for them, the adjective liberal often does mean “not radical.”

Walzer offers several reasons for excluding at least some committed religionists from the ranks of those who can pursue their ideals wholeheartedly, even radically, while still being considered liberal. Religions, to begin with, are often “greedy”: they ask a lot of us in terms of time and belief. They make “radical and exclusive claims on their members’ emotions and on their everyday commitments.” They might make us be somewhere on weekends—or every day, or several times a day. They might demand that we only eat certain things. They might tell us to marry our own. They might mandate different roles for men and women. They might require that we think certain things, or at least publicly affirm a certain creed. Most damningly, they usually insist that they are right—and by extension, that those of other faiths, or differently practicing coreligionists, are wrong. Yet this is precisely how billions of people experience religious life. It’s the norm, not the exception. Walzer’s arguments would leave whole continents of humanity outside the liberal tent.

Walzer’s stance here poses a special challenge for Orthodox Jews, particularly those who are citizens, as I am, of the State of Israel. Many Orthodox Israelis, to be sure, wish to have as little to do as possible with a society governed by liberal principles, but many others wish to find their place in it. The considerable number who are now protesting Israel’s judicial revolution with signs reading “Religious. Zionists. Democrats.” are all members of “greedy” associations (though some probably have hobbies too). “Religious dogmatists, whatever the dogma, probably can’t be liberal,” Walzer writes, denying them the precious adjective. Must that be so? Although these Orthodox protesters likely agree with Walzer that there are “different ways of being . . . a Jew,” they probably define those ways in terms of Jewish law. They oppose persecuting heretics, but they might well think that attaining the “world to come” requires true beliefs. They probably reject the violent messianism of the settler fringe, but they pray three times a day for the restoration of the Temple, the Davidic monarchy, and divine rule. Not all Orthodox Jews are dogmatists, but many are, and among their number are some of those who have assembled every motzaei Shabbat for many months to fight for Israel’s democratic future. In their public lives, they epitomize liberal citizenship. In fact, I’d wager that their national solidarity matches or exceeds that of the frummest American civil religionists. And whatever nonliberal practices they have, they keep them voluntary and private, as Locke and other classical liberal theorists demanded. Haven’t they done enough to earn the adjective?

Walzer seems to suggest that religious liberals—unlike democratic, socialist, feminist, nationalist, and communitarian ones—have to be like early Christianity’s Laodiceans: “neither cold nor hot.” Although they might do or think certain things, they should maintain a kind of ironic distance from their beliefs and practices. They shouldn’t allow faith to root itself too deeply into their selves. And they should never claim exclusive possession of the Truth (though they should reject the self-certainty of doctrinal believers). His caution is understandable. Religion can make for truly dangerous politics, as Walzer, whose first book was a study of Puritan zealotry, knows better than most. But excluding the most committed religious people from the brother- and sisterhood of adjectival liberals upends the very purpose of Walzer’s noble project. It is an ultimately indefensible exclusion—this time based on an adjective instead of an ism.

Perhaps there is an alternative. Instead of thinning out and ironizing their religious commitments, believers might instead reinterpret them, as the philosopher John Rawls once proposed. They can try to find the core values of liberalism within their traditions. Walzer, who has performed a tremendous service by editing the multivolume The Jewish Political Tradition, gestures in this direction when discussing the project’s findings in the present book. The rabbis, he says, might be described as liberal pluralists of a sort, but really “all possible political positions are represented” in the tradition. It seems to me that one can be less diffident. In fact, I think the most urgent task of Jewish political theory today is to show how liberalism is compatible with classical Judaism, democracy with the kingship of God. Walzer is a self-described secular Jew who believes “that the ur-language of zealotry is religious,” so this will never quite be his project, but I think that he would recognize it as a liberal one.

Toward the beginning of The Struggle for a Decent Politics, Walzer says that this may be his last book. For the sake of both liberal democracy and Judaism, let us hope not.

Suggested Reading

Thinking About Revolution and Democracy in the Middle East: A Symposium

Since January of this year, revolution has spread across North Africa and the Middle East with such velocity that predicting exactly what will happen next is probably a fool's errand. In this issue, we have asked seven writers to return to their bookshelves and tell us what books, authors, and arguments they find helpful in thinking through the causes and implications of these surprising events.

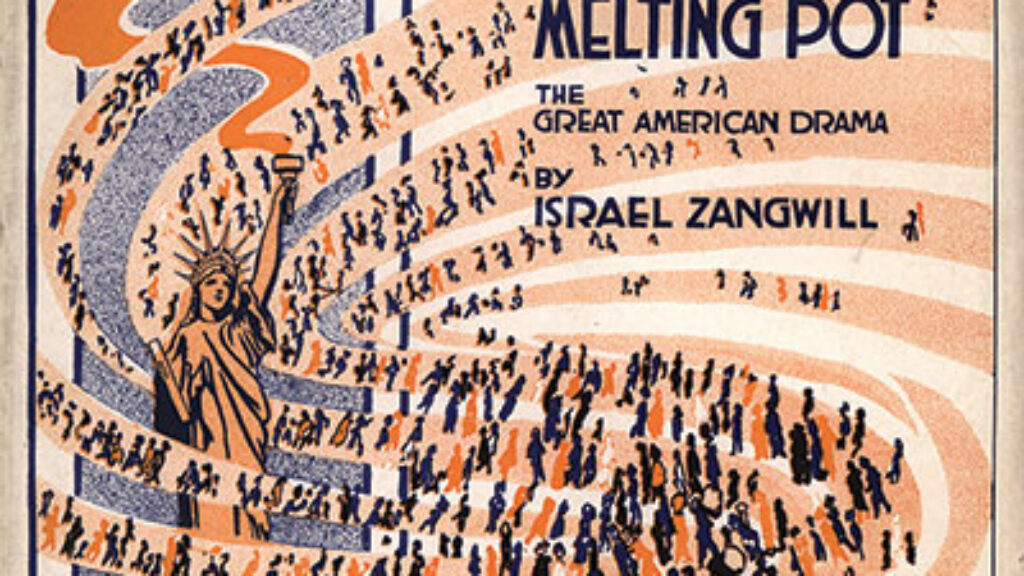

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29

At the age of 29, David Ben-Gurion was speaking to empty halls across America for the Zionist movement and Leo Strauss was finding the “theological-political predicament” insoluble. As for Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, he was in Berlin worrying about epistemology and halakha. Three portraits of Jewish excellence in the making.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In