What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

The heart wants what it wants. Or so we moderns—from Emily Dickinson to Selena Gomez—think. For most of us living in the Western world, Jews and non-Jews alike, it would be unthinkable to have our marriage partners chosen for us by our families. True, in haredi communities, as among educated Indian families, arranged marriage persists as a practice. But even in those circles it is rare for young people today not to be allowed to meet each other and exercise a veto before the deal is done. The era when it was only under the chuppah that the groom and the bride glimpsed each other for the first (or perhaps second) time belongs to the benighted past. But that past, it turns out, was not very long ago. For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

What is truly stunning is how little time it took for this millennia-old practice to collapse. With the advent of the Enlightenment and emancipation—in Western Europe in the 18th century and a hundred years later in the East—it became self-evident almost overnight that young Jewish people should wed out of romantic feeling and shared values, and that their union should, at least ideally, be a companionship based on love. To create such a union, it would be wrong, even perverse, for boys or girls to be forced to marry before their individual characters had taken shape and they had the capacity to choose. As with many cultural changes, this shift in marriage practices, which evolved gradually in European society over the course of centuries, took place among the Jews in less than a generation or two. If you were born in the latter part of the 19th century in Eastern Europe, it is likely that your parents’ marriage was entered into as an agreement between two families, while you insisted upon choosing your spouse for yourself. And all the more so if you emigrated to America.

Naomi Seidman’s learned, insightful, and witty new book The Marriage Plot: Or, How Jews Fell in Love with Love, and with Literature tells this story, but with a twist. Although she amply documents the vertiginous swing away from traditional marriage, she goes on to demonstrate that there was nothing smooth or total about the adoption of the new ideal of romantic love. Behind the public triumph of the new order, Seidman argues, just those components of the ancien régime that had been most vilified —family interest, pedigree, the separation of the sexes, matchmakers—ended up making a surprising reappearance. It was not that they had simply managed to survive the revolution; rather, as Seidman shows, it was a subtler and more interesting process: the emergence from within the space of secularity of new ideas and practices that drew from energy and wisdom of the old system. Literature—Hebrew, Yiddish, and American Jewish literature—is Seidman’s primary terrain. As the subtitle of her study indicates, Jews fell in love not only with love itself but also with literature. The attitudes and expectations about how life should be lived on the part of modernizing Jews were shaped by their avid devotion to the new secular scripture: the novel. Seidman operates adroitly in the territory between literature’s role in representing the realities of Jewish society and its role in forming the ideals and sentiments through which a new generation of that society would seek to live their lives.

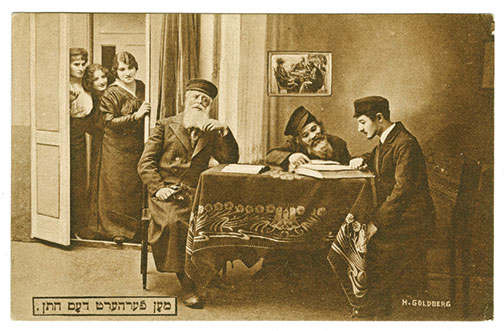

But before showing us how things were turned upside down and then put right-side up (at least partially), Seidman revises our received conceptions about the old marriage system. The glory of traditional Ashkenazi Jewish society, argued the great social historian Jacob Katz, was the wedding of commerce to learning. Wealthy families sought out young Talmud prodigies for their daughters. Through such a match, a boy from a modest background with scholarly talent could hope to raise his fortunes, just as the mercantile family hoped to raise its prestige. Typically, the marriage would take place around the onset of puberty, although the match might have been made, with the help of a shadchan, long before then. The juvenile bride and groom would likely come from different towns and would never have met or seen each other. In a practice called kest, the young couple, hardly teenagers, would board with the bride’s family while the young bride began to bear children and the groom studied in the beit midrash. The dowry money would be invested with a close relative, and at the end of the kest period, which lasted several years—the greater wealth the longer the time—the funds would be used to set up the young man in business or to purchase a rabbinical post.

Relying on the recent research of Hebrew University historian Shaul Stampfer, Seidman urges us to realize that this idealization of the Jewish marriage system fitted only the top one percenters of the day, the lomdim class, the scholarly elite, and their mercantile counterparts. The children of the great majority of Jews tended to marry later and locally—so the bride and groom were likely to have known each other—without the services of a shadchan. And those exceptional Talmud students who made brilliant matches in the late 18th and 19th centuries had tales to tell about the emotional costs of their success. In a stream of autobiographies written by Salomon Maimon, Moshe Leib Lilienblum, Mordecai Aaron Günzburg, and others, former prodigies bitterly describe how it felt to be merchandised by the fathers, ripped from their homes, placed under the thumb of shrewish mothers-in-law, and then, while barely past puberty, expected to perform sexually.

College of Charleston Libraries.)

The old marriage system, it turns out, was felled by a book. This is an exaggeration, of course, but Seidman is not far wrong in pointing to Abraham Mapu’s 1853 historical novel The Love of Zion (Ahavat Tzion) as one of those extraordinary moments in which a literary text served as a flashpoint for a far-ranging shift in social attitudes. Set against the Assyrian threat to the Kingdom of Judah in the 8th century B.C.E., The Love of Zion tells the story of the attraction of the high-born Tamar for a valiant shepherd named Amnon. The lush biblical cadences of Mapu’s Hebrew prose, redolent of the Song of Songs, and the romantically evoked geography of the Holy Land made The Love of Zion an instant best-seller that went through more than 40 editions in a dozen languages. What was revolutionary in the book, in Seidman’s telling, is its showcasing of sexual attraction and romantic yearning as a natural basis for marriage rather than as a transgression against social and religious norms. For young men trapped in early arranged marriages or for even younger men over whom that fate loomed, Mapu’s novel was an exhilarating discovery. “The ethnographer and playwright S. An-sky,” Seidman tells us, left “his hometown of Vitebsk in 1881 in search of enlightenment with four books in his satchel, one on them Mapu’s romance (Lilienblum’s autobiography was another). In 1895, at the age of 14, the future poet and literary critic Ya’akov Fichman ran away from home with just a change of clothes, some food, and his copy of The Love of Zion.”

In the Hebrew and Yiddish novels that followed later in the 19th century, a new conception of marriage emerged. It held that young people themselves, not their parents, should decide about their suitability for each other, and that decision should be based on mutual attraction and a shared outlook on life, not yichus (family descent). Because the decision-making was now up to the young couple, a space of acquaintanceship before marriage opened up for the first time and ushered in unprecedented rituals of courtship. And women, instead of being merely homemakers and mothers, were now seen as bearers of culture and finer sentments capable of taming their husbands’ masculinity. Or so we thought.

It is just here that Seidman’s brilliant contrariness makes its mark. The Jewish adoption of the enlightened, European model of companionate marriage, she argues, was always “partial and ambivalent.”

In the twentieth century, for reasons both literary and sociological, Jewish literature came to embrace what writers saw as traditional Jewish attitudes toward love and marriage, viewing tradition . . . as a source of erotic power. What began as a process of Jewish modernization and Europeanization was transformed into the literary discovery of “authentic” Jewish Eros.

Seidman’s argument has two parts. First, she submits that there are components of the old system that were retained because they express sources of Jewish wisdom about human behavior. Dissatisfied with the overly domesticated nature of the modern European model, Jewish writers were attracted to these submerged survivals of tradition. Her second point is far more ambitious. The 20th-century Jewish writers who were alienated from Judaism found sources of real erotic energy within the tradition, and this discovery had the effect of doing nothing less than Judaizing world literature. The writers she has in mind are Sigmund Freud, Bernard Malamud, Grace Paley, Lenny Bruce, Erica Jong, Philip Roth, and Tony Kushner. These authors, she writes, “contributed to the formation of a modern sexual counter-narrative to the Christian-chivalric models of love.”

The second of the claims, that it was the Jews who helped Western literature get back its moxie, is a wonderfully grandiose speculation that Seidman has time to float but not fully substantiate. The weight of her interpretive ingenuity is spent on fleshing out the first argument, which she accomplishes by revisiting some of the classic works of the Hebrew-Yiddish canon and demonstrating the persistence of elements of the old marriage tradition amidst the ostensible embrace of modernity. Even in The Love of Zion, that font of rebellion, Seidman discerns behind the evils of arranged marriage the operation of a higher principle of fatedness in which the bride and the groom are destined for each other from birth. (It also helps that Amnon turns out to be a high-born shepherd and thus is not without yichus.) Although Amnon and Tamar may be ignorant of this plan and be drawn to each other by mutual attraction alone, ultimately their union is bashert. This principle is also at work in An-sky’s foundational masterpiece, The Dybbuk. The reason Khonen haunts Leah is because the two of them were promised to each other before their births when their fathers were yeshiva students together. “These arranged marriages are in fact love matches, even if the love is between two fathers,” Seidman writes. She takes particular delight in showing how the intense male-to-male bond echoes the passion of the heterosexual lovers:

By setting the marriage arrangements among just-married young men and infusing the oath with mutual friendship as well as erotic attraction, An-sky recasts the generational opposition as a suppressed parallelism, in which fathers and their children are, quite literally, kindred spirits, expressing the same loving impulses in only apparently dissimilar ways.

Also making a surprising return to the stage is the reviled, comic figure of the matchmaker, the embodiment of marriage as a commercial transaction. Yona Toyber, a matchmaker in S. Y. Agnon’s novel A Simple Story, is a figure much beloved in the town of Szybusz on the part of both parents and young people. He differs from his grotesque predecessors because of his intuitive psychological subtlety and the near-invisibility of his actions. Young people fall in love with each other and marry without suspecting that Yona has a role in choreographing their attraction to one another. The fact is that they have fallen in love with each other and would be scandalized by any suggestion to the contrary. Nevertheless, a hidden hand has guided them to make an attachment that will be good for the community as well as for them.

Seidman discovers more varieties of the persistence of tradition in new guises in the works of Moshe Leib Lilienblum, Yehuda Leib Gordon, Sholem Yanken Abramovitsh (Mendele Mokher Seforim), and many others before she proceeds to 20th-century American Jewish writers and her argument about the Jewish influence on world literature. The provocative ambitions of Seidman’s project might lead one to suspect a critical mind given to rash and tendentious generalizations. But the opposite is the case. Seidman is a nimble, curious, omnivorous reader, with whom it is a pleasure to spend time. She moves freely among Hebrew and Yiddish texts and is well-versed in social history. We are prepared to extend credit to her big ideas because we trust the quality of her exegesis of small examples. She uses critical theory rather than being used by it, and she always writes with a clarity that signals a genuine desire to communicate with her readers. She is, moreover, among the small number of scholars who are happy to acknowledge that their original insights have been built upon the research of others.

The Marriage Plot joins a growing number of literary, historical, and philosophical investigations of our post-secular age. It is, in many senses, the story of all of us. We have come of age in a time when traditional religion has long been discredited by the Enlightenment and modernity, yet we construct our lives out of materials repurposed and reinterpreted from that banished tradition.

Suggested Reading

The Jewish Preview of Books—August 2018

So many books, so little time. A quick look at Jewish books being published this month.

History of a Passé Future

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

Letter from Neukölln, Berlin

"Although the warning to hide invoked memories from Berlin in its darkest days, we refused to be afraid of who we are."

The World is Round

The heckler’s guide to beating an antisemite.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In