On the Importance of Booing Mayne Yiddishe Mame

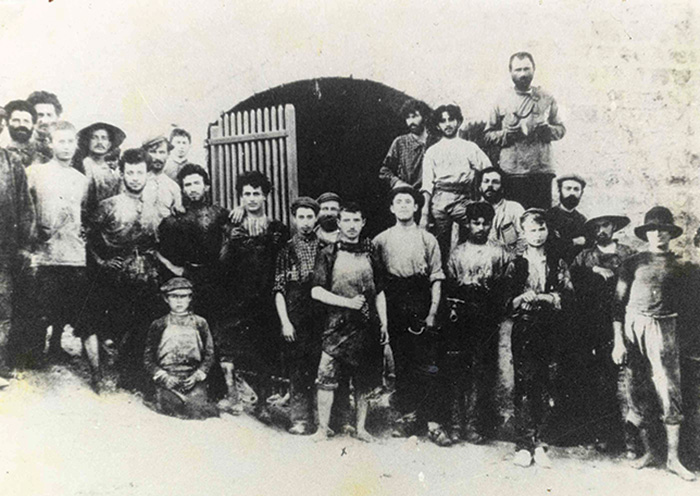

The cover of Gur Alroey’s An Unpromising Land: Jewish Migration to Palestine in the Early Twentieth Century features an iconic photograph of a group of Second Aliyah laborers assembled in front of a winery in the agricultural colony of Rishon Lezion, in 1906 or 1907. A twenty-something David Ben-Gurion, his hair still dark, fairly plentiful, and conventionally coiffed, stands almost unrecognizably in the center of it. The future prime minister, however, scarcely makes an appearance in Alroey’s book, and his fellow pioneers (halutzim) who came to the Land of Israel both “to build and to be built” into Hebrew-speaking tillers of the land are also all but absent. For An Unpromising Land is about the typical Jewish immigrants to Palestine in the early 20th century. They were for the most part, according to Alroey, not ardent participants in the “conquest of labor” but “‘ordinary’ people who left Europe in the hope of finding a better future,” and, for one reason or another, happened to end up in Palestine instead of New York or Buenos Aires. Only after they had arrived in the Holy Land did the small idealistic elite, represented by Ben-Gurion and friends, gradually reshape most of these people into Zionists.

To readers raised on what has long been the standard Zionist narrative and still loyal to it, this may sound suspiciously like an attempt to undermine it, not by villainizing the men and women of the Second Aliyah, the way anti-Zionists do, but by normalizing them. Seen in this light, their struggles in the decade before World War I may seem humdrum, uninspiring, anything but a crucial phase of the “adventure story” retold, for instance, by Anita Shapira in her recent history of Israel. I will here express some doubts about the significance of the evidence Alroey presents to make his case. But the more I consider what he has to say, the more it seems to me that even if it is accurate it doesn’t debunk the old story as much as it renders it, as he himself ultimately acknowledges, more wondrous.

To those who have kept up with the scholarship of the last several decades, it is no secret that the legendary halutzim constituted only a small minority of the Jews who immigrated to Palestine during the decade prior to World War I. More than 30 years ago, the great Hebrew University historian Jonathan Frankel stressed this fact in his Prophecy and Politics. The majority of the Second Aliyah olim were, he wrote, “older people driven by traditional religious motives to come to the Holy Land,” while the true pioneers numbered only in the low thousands.

(Courtesy of the Museum of Rishon Lezion via the PikiWiki project/Wikimedia Commons.)

Alroey’s focus, however, is on neither the pioneers nor the deeply pious but rather on Jews for whom Palestine represented one among several havens from poverty and oppression in Eastern Europe—and not necessarily the most desirable one. They gravitated toward the country’s cities and towns, where they continued to pursue their old professions or something like them. Alroey’s main source with regard to these people’s reasons for engaging in aliyah consists of letters sent to the information bureaus established by the Lovers of Zion (Hovevei Zion) and the World Zionist Organization to educate prospective immigrants to Palestine about the conditions they would face there. Examining 989 letters of inquiry sent by tailors, builders, shoemakers, dentists, students, and others, Alroey concludes that “it seems that the Zionist idea was not a major motivation in the decision to emigrate, and only a few of the applications have a definite ideological coloring.” Indeed, only “10 percent specifically declared their support for the Zionist idea,” although, he acknowledges, in many letters the distinction between ideological and economic motivations is blurry. “However, it is absolutely clear from the content of the letters and from the formulation of the questions that Zionist ideology was not a central concern in reaching the decision to emigrate.”

A few pages later, after quoting several of the letters, Alroey reiterates this conclusion more strongly: “it appears that the role of Zionist ideology as a factor in reaching the decision to emigrate was extremely limited.” Finally, at the end of his book, Alroey goes so far as to say without qualification that “the mass of immigrants who reached the Jaffa Port in the years 1904–1914” were people “who were not motivated by the idea of return to the land of Israel and were not part of the Zionist project.”

It is hard to see how the correspondence he has examined warrants Alroey’s conclusion, in its mild, stronger, or strongest version. The letters are, first of all, the work of people who were contemplating aliyah, not those who actually undertook it, whose motives may have been somewhat different. Furthermore, the letter writers were not seeking clarity about some of the fine points of Zionist ideology but help in figuring out whether they could make ends meet in Palestine. Even the diehard Zionists among them had little reason to do anything other than talk tachlis when they contacted the bureaus.

When Alroey does turn, in the final chapters of his book, to the people who actually settled in Palestine during the Second Aliyah period, his concern is not with their motivation for having done so but with their daily life. He tells us a lot of interesting things about the first candy-making factory in Palestine, which initially had trouble acquiring machinery but which within a couple of years was producing sweets that were reputed to be as good as those from abroad; the early history of the hotel and restaurant businesses in Jaffa; the apartments in which new immigrants lived (the ones in Jaffa were better lit and ventilated than those in the towns of the Pale or, for that matter, the Lower East Side); and other such matters. With respect to the ideology, or lack thereof, of these non-pioneers, however, he has remarkably little to say.

Alroey devotes some attention to the professional associations established by the new immigrants, noting that in general they “had no party affiliation, and their members did not have a concrete ideal of the Yishuv that they sought to put into practice.” The Merkaz Ba’alei Melakha (Artisans’ Center), in particular, had no ideological stance. Although it bore a Hebrew name, it was not pro-Hebrew in principle, and not all of its members were Zionists. But when they came to realize that the struggle for avoda ivrit, i.e., Jewish labor, was in their own self-interest, they drew close to the Ha-po’el Ha-tza’ir party. Economic self-interest soon generated “an ideological connection, and the center, which had been a purely professional association, became an entity with ideological objectives and a sense of national responsibility.”

Perhaps this development, which Alroey appears to regard as paradigmatic, explains the presence of Ben-Gurion and his fellow pioneers on the cover of An Unpromising Land. These people may have been only a small minority, but they were nonetheless destined to place their stamp on things. Alroey is no doubt correct in stressing the transformative role of the nationalist elites in the Jewish community in pre-World War I Palestine. Unfortunately, however, he has left the impression that this vanguard consisted entirely of socialist pioneers. For a much fuller and subtler picture of the way in which the “Zionist nationalizing elites” shaped the culture of the Yishuv in the first period of the Second Aliyah readers should turn to Arieh Bruce Saposnik’s Becoming Hebrew: The Creation of a Jewish National Culture in Ottoman Palestine (2008). Saposnik makes it clear that the process of nationalization involved people besides purposeful elites and impressionable masses. There was “a comparatively broad base of grassroots activists”—individuals “who might not be members of the nationalizing ‘elite’ . . . but who undertook willingly and often participated actively in the project of becoming national—becoming Hebrews.”

In Becoming Hebrew, Saposnik recognizes the importance of Alroey’s Immigrantim (2004), the earlier Hebrew book on which An Unpromising Land is largely based. He described it, however, as a valuable contribution to the study of those Jewish immigrants to early-20th-century Palestine “who were the less enthusiastic subjects of nationalization.” Saposnik’s cautious characterization of some refugees from Eastern Europe seems more apt to me than Alroey’s description of the mass of them as people to whom Zionism was an alien ideology. But I don’t want to leap to conclusions. Perhaps there are stones that have yet to be turned over—diaries, memoirs, old newspaper stories—that future historians might use to shed more light on the rank and file immigrants of the Second Aliyah period.

In her Babel in Zion, Liora Halperin describes how similar immigrants to Palestine during the Mandate era persisted in their diasporic ways. Despite the Zionist movement’s commitment to Hebrew, the newcomers seem to have continued to do most of their reading in other languages. Of the books on the shelves of Tel Aviv’s public libraries, Halperin notes, “59 percent were in languages other than Hebrew in 1934.” This could happen because, despite the Zionist “norm of Hebrew monolingualism,” there was more tolerance for “foreign-language reading in private spaces” than there was for more public linguistic disloyalty. When Yiddish movies first hit the market, for instance, the Zionist educator Yosef Luria tried to discourage the theater managers from showing them, warning that it would certainly “play into the hands of the faithless sons of the nation, the enemies of her revival.” On September 27, 1930, members of the Battalion of the Defenders of the Hebrew Language protested the screening of Mayne yiddishe mame at the Mograbi Theater in Tel Aviv. When they failed to prevent it, they infiltrated the theater, then booed and hurled foul-smelling objects at the screen when the talking began:

As crowds gathered to protest the first screening, Mayor Dizengoff issued an order to the police to prevent the second screening. Eventually, a compromise was reached: all the talking and singing parts of the film would be excised, and the show would go on.

The word of mouth on this movie, in Palestine at least, must have been less than favorable.

It was easier to keep Yiddish off the screens than off the streets, which were often crowded with peddlers hawking alte zakhen and street food in their native tongue. The arrival in the mid-1930s of masses of German-speaking immigrants generated a different sort of threat. In 1937, for instance, Weller’s Syrup and Jam alerted customers to a decrease in redemption for glass jam jars in an advertisement written in six languages: English, Hebrew, French, German, Russian, and Polish. A private citizen complained to the Tel Aviv municipality that this was “a sad reminder of the lawlessness [hefkerut] that has taken root in our city.” Mayor Israel Rokach quickly wrote to the Union of Industrial Owners about this “insult to the public.” The head of the union expressed his regrets and “promised that the union would engage in ‘personal propaganda’ to appeal to its members to change their advertising.”

More threatening to Hebrew than the languages of the countries from which the Jewish immigrants had come was the language of the colonial power governing Palestine: English. It was an uphill struggle to get the British administration to live up to its promise to treat Hebrew as one of the official languages of Palestine. “Over the course of thirty years of British rule, English had emerged as not only the language of administration, but also an arbiter of social power more broadly, the linguistic gateway toward individual and collective success, even within a society deeply committed to the principle of Hebrew exclusivity.”

Halperin does not suggest that people’s recourse for one reason or another to languages other than Hebrew was a defection from Zionism. It would be wrong, she says, to imagine “a rhetorical divide between pro-Hebrew, Zionist Jews and apathetic, foreign-language-using, non-Zionist Jews.” Some immigrants were just being practical, relaxing in the language that came easiest to them, or acquiescing to the limits of their own linguistic abilities. In doing so they contributed to the flourishing “of linguistic diversity in a society officially committed to the promotion of a single tongue.”

Neither Alroey nor Halperin inspire the reader with a tale of how the heroic Zionists pursued their shared goals in unity. Both of them highlight the degree to which the Zionist leaders’ struggle to create a new national identity had to be carried on with the aid of a rank and file whose ideals did not match their own. Alroey may overstate the extent to which Jewish immigrants during the Second Aliyah period were remote from the national project, but if he does so it is with the knowledge that this only magnifies the achievement of their leaders. “Paradoxically,” he writes in his conclusion, his book

ascribes much greater power and significance to the pioneers and Zionists than previous historians who have represented immigration to Palestine as something unique and unparalleled in history. The pioneers were a minority that formed the consciousness of the majority and thus succeeded in harnessing it to the national enterprise.

Halperin, for her part, makes no proud claim on behalf of the battlers for Hebrew monolingualism in pre-state Palestine. But her book’s vivid depiction of the challenges Hebrew faced between 1920 and 1948 suggests that its success was not inevitable. One is left with an even deeper appreciation for the fierce figures that enabled it to prevail.

Suggested Reading

Redesecration and Solidarity in Greece

“Even if they vandalize the monuments one hundred times we will repair them one hundred and ten times,” pledged Yiannis Boutaris, the mayor of Thessaloniki, after the latest act of anti-Semitic destruction in the city.

Another Round with Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer had the gift of enlivening everything he touched. And he touched almost everything, from politics to Hollywood to Sports. But his Jewish novel stayed in the drawer.

What’s Love Got to Do with It?

Shai Held measures up the sprawling mass of Jewish tradition and claims, against incredulous critics going back to Saint Paul, that love has a great deal to do with it.

Brave New Golems

As monsters go, golems are pretty boring. Mute, crudely fashioned household servants and protectors, in essence they’re not much different from the brooms in the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” story.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In