What’s Love Got to Do with It?

At five o’clock in the afternoon, in James Joyce’s Ulysses, Leopold Bloom finds himself in a Dublin pub, arguing over the meaning of life with a band of incredulous Christians. In an impromptu speech decrying “‘force, hatred, history and all that,’” Joyce’s wandering Jew blurts out his philosophy: “‘Love,’ says Bloom, ‘I mean the opposite of hatred.’”

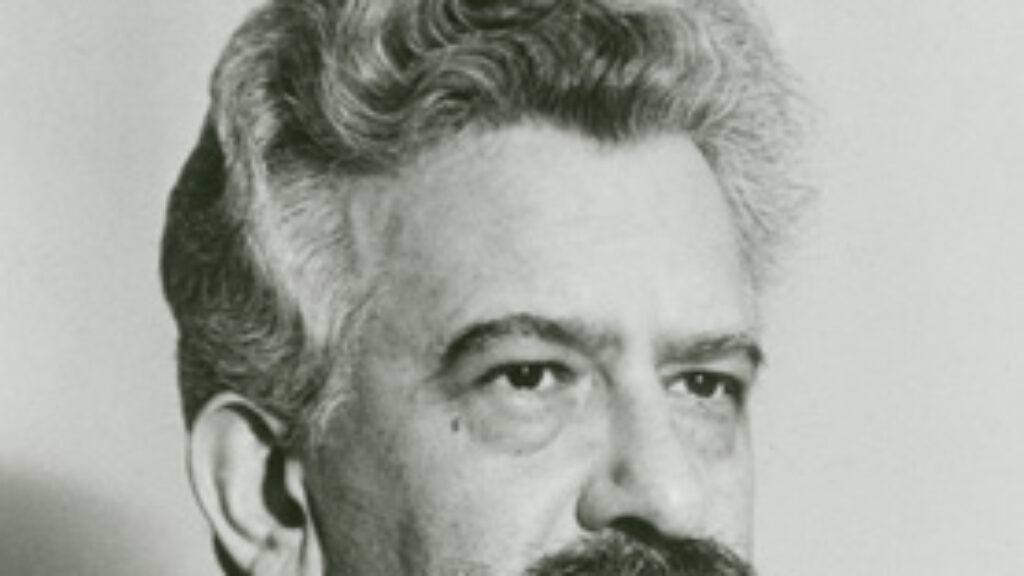

Shai Held’s new book, Judaism Is about Love: Recovering the Heart of Jewish Life, is not a stammered tautology but an elaborate treatise, blending polemic and apologetics with theological insight and moral exhortation. But, at heart, it makes the same argument. Held measures up the sprawling mass of Jewish tradition and claims, against incredulous Christians stretching back to Saint Paul, that love has a great deal to do with it.

Held understands the many levels on which this claim seems counterintuitive. “All this talk about divine love,” he writes, “may strike some readers as . . . well, unJewish.” Primary culpability for this misconception lies with “centuries of Christian anti-Judaism,” starting with the evangelists’ depiction of Jesus matching wits with two-dimensional pharisees and Paul’s later articulation of love versus law as the thumbnail of Christian-Jewish difference. But Held seems even more concerned by its internalization among his fellow Jews, which he regards as both tragic and unnecessary. For his part, he describes a Judaism devoted to “a God of love who summons us to lead lives of love.”

Drawing on biblical text and classical midrash, rabbinic sources from the Talmud through Hasidism to the modern period, and a daunting array of contemporary moral philosophers, Held leads the reader through the many implications of his argument. Some are commonplace, as when he cites the talmudic teaching that one who “‘destroys a single life, Scripture charges him as though he had destroyed an entire world,’” to suggest that “we matter, but so too does everybody else—without exception.” Others penetrate deeper, as when Held suggests moral indignation is a manifestation of love, invoking a tale from Genesis Rabbah about Abraham witnessing a “palace in flames.” He writes:

This refusal to hide or look away is, I think, a manifestation of deep love. Faced with a world afire, Abraham will not grow calloused or indifferent. He continues to care, even when it hurts. And so he cries out.

In a 2011 speech, Held described cultivating such moral engagement in his students at Mechon Hadar, the egalitarian yeshiva he cofounded and helps lead: “We teach a Torat Hesed, a Torah of love and kindness, a Torah that reminds us that every step we take towards God is a step towards—not away from—the world.”

Held distinguishes this approach from the purported universalism of Christianity and defends a loving Jewish particularism:

Since Jews have traditionally understood themselves as members of an extended family, we have seen ourselves as having more intense obligations to our fellow Jews than to others . . . [but] having a more demanding set of obligations to our family emphatically doesn’t mean that we have no obligations to others.

Elsewhere, he writes more specifically about the Jewish family itself, offering a vision for moral renewal while critiquing some of its current values: “Let students be given the unequivocal message: how kind you are and how much chesed you do are far more important than which colleges do and don’t accept you.”

Held’s first book was an excellent critical study of Abraham Joshua Heschel, and he remains deeply influenced by the old master. In that earlier work he discussed the theological import of Heschel’s high-flown literary style:

Heschel communicates as he does because he wants to galvanize the heart as well as the mind . . . the goal of theology is not, ultimately, to know something about God, but to know God, and this demands passion, not just cognition.

Held does not aspire to Heschel’s verbal incandescence, but his work is also an effort to root cognition in passion—to predicate knowledge about what God wants on a presumed encounter with the divine presence.

Heschel’s emphasis on passion was linked to his critique of what he called “pan-Halakhism,” the idea that living within the “four cubits of the law,” as defined by rabbinic tradition, was all that Judaism required. As Heschel well knew, Judaism actually has a rich tradition of moral and theological attempts to galvanize Jewish hearts, from Bahya ibn Pakuda’s medieval work Hovot Ha-Levavot (Duties of the Heart) to Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s early modern Mesillat Yesharim (Path of the Upright) and beyond. These were all efforts to articulate an ethical religious passion that precedes and infuses the legal fulfillment of the commandments. But both Heschel and Held differ from their forebears in deemphasizing the necessity of inserting this galvanized heart back into the halakhic body. Without rejecting traditional religious practice, each defines the Jewish heart’s primary burden as engagement in the struggles of contemporary life and society—crying out when the world is aflame—rather than fulfillment of the mitzvot, per se. Heschel famously described this approach as one of “moral grandeur and spiritual audacity”; Held, more modestly, speaks of Judaism as requiring “a step towards—not away from—the world.”

Though Heschel’s impact on Held is evident, differences emerge in the details. Each argues in terms of a passionate relationship between humans and God that mandates moral engagement with the world rather than spiritual withdrawal. But where Held speaks of a nurturing love—ahavah—Heschel champions wonder. As Held has himself noted, Heschel’s wonder corresponds to the rabbinic word yirah, more frequently translated as “awe” or “fear,” as when the pious are described as possessing yirat shamayim, a fear or awe of heaven. “Wonder, for Heschel,” wrote Held, “forces us to recognize that we are not the only source and judge of value in the world. . . . A world without wonder is a world devoid of self-transcendence, and thus a world closed off to the presence of God.” Heschel’s wonder is ultimately experienced as an inspiring religious sensation, but it retains the moral stringency of traditional yirat shamayim; it arrests the metastasizing human ego in apprehension of the unfathomable Divine.

Held’s focus on God’s ahavah is comparatively warm and fuzzy. It is also more tentative. In his introduction he writes:

When I talk about a God who loves and cares about the dignity of every human being, I am aware that there are readers who will wonder how on earth can anyone still believe that? I am aware not least because I too hear those voices, both in my heart and in my head. In this day and age, I think, a theologian has to be able to imagine secularity from the inside.

This is a disarming confession. It also raises at least two significant questions: what kind of claims are really being made by a theologian who can “imagine secularity from the inside”? And who is he really speaking to?

One might contrast Held’s appealing hesitancy with Heschel’s excoriation of those who fail to experience the Bible as revelation. “No sadder proof can be given by a man of his own spiritual opacity than his insensitiveness to the Bible,” Heschel wrote in God in Search of Man. In his study of Heschel, Held at first generously suggested this caustic admonition might be just hyperbole, meant to “jolt [the reader] into considering possibilities that modernity has ruled out of hand.” But, he concluded, “Heschel’s statements may inspire some readers, but they likely alienate many others.”

Like Heschel, Held is a biblical theologian, deriving his vision of religious life from the textual legacy of the God of Abraham rather than abstract philosophizing. But a tension, if not a contradiction, in his project lies in the impression that he is trying to articulate a doctrinal Judaism of relevance to the nonbeliever—a theology that can function, on some level, whether or not its god actually exists. The high drama of Heschel’s oeuvre, by contrast, is the drama of faith. Heschel’s God, however implausible it may seem, really is in search of man.

Although Held speaks frequently of God, his ultimate subject is Judaism. His argument hinges more directly on the love embedded within the religion than the reality of the God who reposes beyond it. The end result—and this is no small thing—is a compelling Jewish devotional framework, aimed as much (if not more) toward potential “as if” practitioners as true believers.

But, God aside, how persuasive is Held’s argument that Judaism is fundamentally about love? With characteristic intellectual candor, Held admits that, like any theology, his loving version of Judaism is based in a certain amount of selectivity:

To inherit a tradition is to make decisions, whether conscious or not, about which texts and ideas to place at the center, and which to treat as more marginal. If someone wanted to, they could presumably write a book entitled Judaism Is About Hate, and marshal an abundance of sources to bolster their case.

Held’s Judaism of ahavah is certainly not a wholesale invention, and his emphasis often provides truly refreshing readings of familiar sources. To study biblical and rabbinic texts with Held is often to see them persuasively recontextualized as elements in a distinctive Jewish pathway of profound meaning and solace. The inspiring Judaism that comes into view differs markedly from Christianity but is no less imbued with love.

Yet, there are moments when his argument wears thin. One might ask if the effort to center Judaism around love isn’t itself an internalization of Christian prejudice, as if the minority must seek validation by squeezing itself into the majority’s hegemonic categories. For all the beauty in Held’s theology, it also runs the risk of leaving those who don’t emblazon their Jewishness with the banner of love—from secular-culturalists to haredi Jews—even further open to denigration.

Beyond that is the terrible question of whether love, as a theological watchword, really speaks to the full reality of the world we now inhabit. Held himself hedges on this one. At the end of a discussion of whether we must extend chesed even to our enemies, he writes:

If human beings—even awful murderous ones—are created in God’s image, then perhaps we are forbidden—for religious reasons—from hating them. If we love God, we cannot hate what God has made. Is this right? Again, I am not at all certain.

It is another honest uncertainty, of a kind Held occasionally offers up when his argument is stretched to its outer limits. At such times, he seems almost like a medieval cartographer who has printed “here be dragons” on the abyss at the edges of the known world.

Or, if you will, it’s as if he has brought us back around to Barney Kiernan’s public house, in the late afternoon, where Joyce’s Bloom is pleading his case against the looming adversary. Only it isn’t exactly Gentile or Jew but those darker powers, which, despite his abjuration, still threaten to obscure the sputtering love-light. You know, “force, hatred, history and all that.”

Suggested Reading

The Audacity of Faith

The career and life of Yehuda Amital—unconventional, unpredictable, and free of clichés.

Hardware, Software—or Love?

Maimonides’s Abraham was a natural philosopher who discovered God through reason, but the biblical Abraham did nothing at all to earn God’s election.

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Who Is David?

Scholars and lay readers remain fascinated by the biblical stories of David and the history behind them, as a new batch of books shows.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In