A Life with Consequences

In 1986, when I first met Yitzhak Rabin, he was the defense minister in Israel’s national unity government and I was a member of President Reagan’s National Security Council staff. In the ensuing years, during the Bush and Clinton administrations, I met and talked to him often, especially when I held senior positions, including that of the lead American negotiator on the Arab–Israeli peace process. Whenever I read another book about him, I naturally do so with a curiosity informed by my own set of intense experiences with the man who was one of Israel’s greatest leaders.

I have to admit that in approaching a new biography of Rabin, I did not expect to gain a great deal of new insight into the man and the country he served. And yet, much to my surprise, I did so in reading Itamar Rabinovich’s Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, Leader, Statesman. Rabinovich is a distinguished historian of the Middle East, but he, too, brings his personal history with Rabin to the biographical task. In 1993, Rabin appointed him to be Israel’s ambassador to Washington, during which time he also served as Rabin’s negotiator with the Syrians. His book tells a very revealing story that ties the arc of Rabin’s life to the course of Israel’s history from the pre-State period to the 1990s.

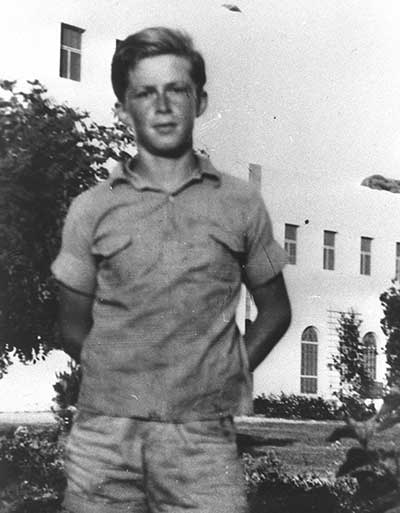

In the chapter Rabinovich devotes to Rabin’s early years in Mandate Palestine, we meet a shy 15-year-old who attempts to explain himself to a friend in his youth group: “I may have a sense of inferiority because I do not have the confidence that the members are interested in me.” A few years later, after he graduated from the Kadoorie Agricultural School, the shy youth’s loyalty to his peers and their cause outweighed any careerist inclinations. He passed on the chance to study water engineering in California and enlisted in the Palmach. Soon establishing himself as an expert military planner, tactician, and operator, the 26-year-old Rabin commanded the Harel Brigade in the fight for Jerusalem during Israel’s War of Independence. This experience left him profoundly convinced of, among other things, the need for military preparedness. “I was bothered by the question,” he later wrote in his memoirs, “why has this war caught us so ill prepared? Was it necessary?” From the armistice talks in Rhodes in 1949, in which he was a participant, he learned from Israel’s surrender of its leverage in negotiations with Egypt that it should never deal with the Arabs in a collective setting but only bilaterally.

Rabin’s complicated relationship with David Ben-Gurion and his problems with Moshe Dayan prevented him from rising through the ranks of the IDF as rapidly as his military performance might otherwise have led an outside observer to expect. Although Ben-Gurion had promised to name Rabin chief of staff, it was his successor, Levi Eshkol, who finally did so, in 1963. The two worked well together until the trying weeks in May of 1967 before the Six-Day War—when Rabin found himself caught in an impossible position between a divided Israeli cabinet led by a hesitant Eshkol and a highly combustible general staff. Driven to exhaustion, and even put—briefly—out of commission, Rabin quickly rallied and implemented the spectacularly successful war plan for which he was largely responsible.

Justly celebrated as a hero, Rabin decided to leave the military and enter politics, but not directly. Feeling that he needed a period of transition, he asked Eshkol to appoint him to be Israel’s ambassador to the United States. Serving in that position during the last year of the Johnson administration, he did not get on very well with President Johnson or those in Dean Rusk’s State Department, who were pushing for complete Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai and not requiring from Egypt a peace treaty in return. In a tart memo written on November 15, 1968, which Rabinovich quotes, National Security Advisor Walt Rostow wrote, “Rabin feels we’ve changed our position and undermined Israel’s bargaining position. The fact is that this has been our consistent position for over a year, but the Israelis have turned off their hearing aids on us. As for undermining their position, we can’t afford to go along with their bazaar haggling if we’re going to have any chance of peace.” The advent of the Nixon administration turned things around.

Rabin forged a close relationship with Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, and the two together regularly circumvented both the State Department and Israel’s foreign minister, Abba Eban. Eshkol’s successor as prime minister, Golda Meir, both saw Rabin’s value and at times felt he exceeded his authority, acting as if he were already a minister. She felt he got out in front of what she was ready to do, especially with respect to an interim pull-back from the Suez Canal in response to Anwar Sadat. Rabin, for his part, was often frustrated by the inability of the Meir government to explain what it was ready to put on the table in order to achieve peace. By the end of his tenure in Washington, their relationship had soured, with Rabin believing that the prime minister had not fulfilled a promise to make him a minister. He returned to Israel in March 1973 ready to run for the Knesset elections on the Labor Party list.

The 1973 war was traumatic for Israel. The surprise attack, the Arabs’ use of oil as a weapon, the terribly high casualties, and the widespread sense of vulnerability after the conflict—so different from the exultation after 1967—all combined to darken the mood and shake the faith of the Israeli public. When the Agranat Commission issued its report on Israel’s intelligence failings at the beginning of the war, Golda Meir was not called on to resign, but massive demonstrations against the government spearheaded by reserve soldiers forced her to do so 10 days later. Rabin bore no stigma from the war, having been outside the government at the time; what’s more, his high standing after 1967 made him an attractive leader for the Labor Party. Since that party then dominated the Knesset, it was able to pick a successor to Meir without a country-wide election. Though Rabin had not established a political network within the central party machinery, Pinhas Sapir was a major power broker within Labor and his backing made it possible for Rabin to defeat Shimon Peres in a contest for the party leadership. On June 3, 1974, he became the prime minister of Israel.

One of the fascinating features of Rabinovich’s book is his discussion of the problems Rabin faced during his first term as prime minister and the degree to which these problems were bound up with his bitter rivalry with Peres. The tension and clashes between the two leaders limited the effectiveness of the Rabin government and contributed to the general sense that the Labor establishment had been in power for much too long—factors that would contribute to the Likud victory in 1977.

Rabinovich also highlights Rabin’s inability to stand up to the settler movement—even though he publicly called the settlers “a cancer in the social and democratic tissue of the state of Israel, a group that takes the law into its own hands.” This failure can be attributed to the weakness of Rabin’s government, and the fact that Peres and others within Labor supported the settlers at this time. Kissinger and King Hussein would have liked a limited disengagement on the West Bank to parallel the ones that had been implemented with both Egypt and Syria, and Rabin saw that such an arrangement could help Jordan replace the PLO as the representative of the Palestinians, but he still judged his domestic position to be too weak to pull off such a plan. Rabinovich repeatedly depicts Rabin as having foregone opportunities to effectively counteract the settler movement as well as the PLO.

It is not that Rabin was wholly ineffective during his first stint as prime minister; he concluded the second interim agreement that set the stage for peace with Egypt and also gained deep strategic commitments from the United States. Moreover, the spectacular Entebbe rescue operation was vintage Rabin—he did not rush to judgment and consistently challenged the military to come back to him with a plan that could be expected to work. (Though this operation restored a great deal of confidence in Israel’s military daring and effectiveness, it, too, was followed by skirmishes between Rabin and Peres over who should get credit for it.)

But Rabin was not skillful at handling the press, the coalition, or his party. On the brink of the 1977 elections he resigned after the revelation of his wife Leah’s (then illegal) overseas bank account—which seemed to fit into a narrative which included far more egregious instances of corruption among the Ashkenazi Labor elite and connected this to their distance from Mizrahi voters, those Jews of Middle Eastern origin who felt neglected, disadvantaged, and treated as outsiders by the Israeli establishment. In 1977, these voters turned to Likud and have rarely paid heed to Labor since, except when its leaders have had unimpeachable security credentials.

Rabin, of course, did have them. Following the Begin-Sharon debacle in Lebanon—which Rabin had warned against—Labor regained enough of its strength to participate in national unity governments, and Rabin served as defense minister from 1984 until 1990. His image, authority, and credibility were restored. When Peres brought down the national unity government in 1990 in response to Yitzhak Shamir’s opposition to an American formula for Palestinian representation at an Israeli–Palestinian dialogue, and then failed to create a Labor-led government, Rabin was displeased. Always the pragmatist, he believed that it was still possible to work with Shamir, and that it was, in any case, better to be in the government than outside of it. Yet he himself was the ultimate beneficiary of Peres’s move, since he soon regained control of the Labor Party and then led it to an electoral victory over Likud in the 1992 elections.

Rabinovich’s discussion of Rabin’s second term as prime minister is written from an insider’s perspective and makes for especially interesting reading. Determined to learn from his mistakes back in the 1970s, Rabin believed that the First Gulf War had brought about a unique moment in the Middle East, and focused his efforts on making peace with the inner circle of Israel’s neighbors in order to better position Israel for the threats he expected to arise from Iran and Iraq.

This discussion of Rabin’s peace policy reminds me of the adage that where you stand depends on where you sit. Rabinovich feels the Clinton administration was let down when Rabin decided to go with the Oslo breakthrough, concentrate on the Palestinians, and put the Syrian track on the back burner. The Americans were dismayed, he writes, that Rabin did this after putting in their pocket a statement of his readiness to withdraw fully from the Golan Heights if Israel’s needs were met.

From my vantage point, as the State Department’s special Middle East coordinator, things looked rather different.

When Secretary of State Warren Christopher presented Rabin’s position to the Syrian president more as a commitment than a hypothetical possibility, Assad’s response was not to treat it as a historic breakthrough but as a reason to begin to bargain over Israel’s needs. As far as Rabin was concerned, Christopher had gone too far. “He felt,” Rabinovich writes, as if “the rug had been pulled out from under him.” Assad had pocketed what had been conveyed without giving anything back. Rabinovich is certainly correct when he says that Christopher (and I) believed that Assad had in fact responded favorably. But that was because we expected him to begin to negotiate and try to grind the process out—Assad was never one to move in leaps. We were not, however, disappointed by the Oslo breakthrough—only surprised because Rabin had consistently downplayed it with us, even during the meeting in which Rabin made what we understood to be a historic move with respect to Syria.

In August 1993, I went with Christopher to meet Peres and Norwegian foreign minister Johan Holst at the Point Mugu naval air station in California to hear about the breakthrough with the PLO. In asking Christopher to meet them, Rabin again conveyed some skepticism about the breakthrough and wanted to know what we thought of it—perhaps because he had kept us in the dark about it. Rabin- ovich, who was also at Point Mugu, is also right to say that Peres was clearly nervous about what our response would be. But there was no holding back on our part. We understood that an existential conflict between Israelis and Palestinians was crossing a historic threshold—even if, as I would tell Christopher at the time, the Declaration of Principles were more aspirational than tangible, and the hard work would await all of us.

True, we wanted to preserve the Syrian track, but, in reality, so did Rabin. Part of his pattern was to use each track as leverage against the other, which was perhaps a reflection of what Rabinovich describes as the lesson that Rabin learned from the unhappy experience of negotiating with the Arabs as a collective in 1949. This is a larger point that Rabinovich makes in this very readable and important book: Rabin was a realist who saw peacemaking not as the source of security but as a further development that needed to be based upon security. He understood that demographics argued for separation from the Palestinians. In 1994, he told me that he would build a separation fence. Even though he preferred to negotiate an agreement, he could not count on reaching one with the Palestinians and, one way or another, there would be a partition of the land.

In his book’s prologue, Rabinovich writes:

Most deaths are simply the end of a life. A political assassination, however, is unlike any other form of death. It is a death that acquires its own significance; a death with consequences. An assassination is not only the terminal point of a person’s life but also the starting point for a new reality the death itself has created.

In his epilogue, Rabinovich discusses the new reality created by Israeli extremist Yigal Amir’s assassination of Rabin. He writes with characteristic sobriety of the peace that might have been, but he does so with a sense of possibility, not certainty—much like Rabin, in this respect. Rabinovich is wistful only insofar as he seems to say that the landscape of the Israel Rabin tried to save may be changing now as a coalition heavily influenced by religious nationalists and settlers is governing the country.

One thing is certain: Rabin could not have made peace by himself. It takes two sides to conclude a genuine peace agreement, and I am dubious that the Palestinians are up to the task. But I am also confident that Rabin would not have let Israel become a binational state. Whether Israel will have the political leadership to prevent that outcome is something that only time will tell.

Suggested Reading

Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Remembering Herman Wouk's "gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans."

Freedom Riders

There is nothing subtle about the theme that runs throughout Philadelphia's National Museum of American Jewish History.

Who Is Man?

Two new books on sin and temptation.

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In