No Simple Return

Hildegard Dina Löwenstein was born twice by her own account—first in Cologne in 1909 and then again in 1951, after her mother died and she began writing poems.

A new birth meant a new name. Someone told her to name herself after an island, so Löwenstein took the nom de plume Domin to honor the country that had saved her when she was forced to flee Nazi Europe in 1939: Santo Domingo, now the Dominican Republic. It was a country facing its own internal political crisis as a brutal dictator, Rafael Trujillo, began accepting refugees from Europe in an attempt to deflect attention from his recent massacre of tens of thousands of Creole-speaking Haitians and to make his own country more white. In retrospect, Domin reflected, “One couldn’t be grateful to the dictator and one couldn’t not be grateful; he was a terrible savior.”

If there was a third birth, it was when Domin returned to Germany in 1954, after more than twenty-two years in exile. There, she found her poetic voice and became a national figure in less than five years. Her first collection of poems, Only a Rose for Support, established her as a leading lyric poet. In a celebratory piece written near the occasion of her eighty-fifth birthday, her friend, the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, a leading student of Martin Heidegger and founder of the influential Philosophische Rundschau, wrote that Domin wasn’t a poet of exile but rather “the poet of return.” This was a crowning moment. Domin was a German poet for the German people, taught in schools, awarded accolades. Colleagues, including Paul Celan, were jealous of her spectacular triumph. But the competition was never a deterrence as she navigated the male world of German poetry, eventually receiving almost every major cultural award, including the Nelly Sachs Prize, the Friedrich-Hölderlin-Preis, and the Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, to name a few.

But Domin remains largely unknown to English-speaking audiences. When she died on February 22, 2006, in Heidelberg at age 96, her work had still not traveled across the Atlantic Ocean. It is only now, nearly twenty years after her death, that her work is appearing for the first time in English translation—in two simultaneously published bilingual editions.

It’s difficult to say why Domin has not gained an international reputation yet. Perhaps it is because she returned to Germany after the war. Perhaps female German poets have yet to be celebrated like their male counterparts, or perhaps it is because her work has simply not found its time yet. The critic Walter Jens said Domin’s work achieved “perfection in plainness.” That could be another reason. There is an air of earnestness and sincerity about her poems—they don’t perform linguistic tricks (they are not, as we say today, “shareable”). They are highly specific, idiosyncratic, and beautifully ordinary. Reading her, one is filled with a sense of natural wonder, and I think by plainness understood as humanness—the kind of humanness that wrestles with trying to find one’s place in the world.

Domin was a complicated figure, and the titles of the first two collections of her work to be translated into English reflect different sides of her personality: Sarah Kafatou’s With My Shadow and Mark S. Burrows’s The Wandering Radiance. Their respective titles—both taken from Domin’s poems but seemingly at odds with one another—reflect the translators’ distinct approaches to portraying Domin’s life and work.

Kafatou, whose translations hit more on an emotional register, is unable to liberate Domin from her shadows, for better and for worse. Burrows, whose volume is benefited by a foreword written by Domin’s biographer, Marion Tauschwitz; a critical introduction; and an essay by Domin on exile, is committed to a political vision of Domin’s poetry that wants to see it shine on the dark landscape of our world today.

The word at the center of their dispute is dennoch, which in German means “nevertheless.” Kafatou writes, “Her poetry is sorrowful, steeped in insecurity and loss, yet her favorite, and the most hard-won, of all her key words was dennoch, ‘nevertheless.’” Whereas Tauschwitz, who Burrows follows, reads this dennoch as a sign of Domin’s resilience and courage in the face of shadows:

Poems became a solace, becoming what she called “songs of encouragement,’’ because she refused to remain in pain and countered melancholy and lament with a defiant “nevertheless’’ (dennoch) that had the capacity of wresting consolation even from misery.

Domin’s poems draw from the tradition of German romantic poetry and are informed by the principles of the Enlightenment. It can be tempting to claim Domin only as a Holocaust poet who gave voice to the suffering of many who were forced to flee their homelands, but the particularity of her experiences as a Jewish German woman also gives voice to a more universal condition of feeling adrift in the world, surrounded by things, trying to create an aesthetic to live in, only to realize that all beauty is ephemeral.

In her introduction, Kafatou writes that “Hilde understood her own Jewishness not as a religious, cultural, or ethnic identity but in terms of inclusion in a Schicksalsgemeinschaft, a community of people exposed, not through their own choice, to particular consequences. In this way she both understated and universalized it.” Schicksalsgemeinschaft means “common destiny”—for Domin, this refers to the more universal condition of wandering and longing for Geborgenheit, an untranslatable word that means “being sheltered,” “held tenderly,” and “saved.”

Kafatou, who knew Domin, has sympathetically rendered a work as tender as it is beautiful, trying as it is controlling. There is a quiet intensity that stalks her translations—for example, in the poem “About Us”:

In later times they will read about us.

I never wanted to inspire pity

in schoolchildren in later times.

Never to appear like that

in a schoolbook.

Compare this with Burrows’s translation:

One will read about us in times to come.

I never wanted to arouse the sympathy

of schoolchildren in later times.

Never wanted to be mentioned

in a school lesson like this.

Sitting next to Kafatou’s work, you sense the distance, remove, and almost sternness of Burrows’s translations, which insist on portraying Domin as a woman without vulnerability. Kafatou’s translations allow one to sense both Domin’s self-

possession and her insecurity. In this example, Kafatou begins with a preposition, which invites you in. There is an immediate sense of intimacy for the reader. She ends the first line with “us,” while Burrows’s opening word, “One,” creates a sense of distance. The “us” in his translation falls in the middle of the first line and transforms it into an imperative statement as opposed to a reflection. Kafatou keeps the repetition of “in later times” from the original German, which Burrows avoids. And the final line, “in a school book,” cracks open the outer shell of the poem with its hard -ck sound, as opposed to the implacable indifference of Burrows’s “this.”

In the title poem of Only a Rose for Support, Domin meditates on the absence of security while trying to make a home in exile:

But I lie in bird-feathers, cradled high in the void.

I’m dizzy. I don’t fall asleep.

My hand

reaches for a firm hold and finds

only a rose for support.

Here in Burrows’s translation, it’s almost as if Domin is cradled in a nest, high up in a tree, and dizzy from the height, unable to sleep. Her hands reach out for something to hold and find only a fragile, thorny rose. Perhaps there’s a shock of consolation in its beauty, upon discovering what one is holding. In Kafatou’s translation, the poet is lying in a bed of feathers, high above the world, reaching her hand out for something to put her weight on and finding only a rose. Both translations are beautiful, though Kafatou’s strays a bit more from the original.

Hands reappear in Domin’s poems. Hands, fingers, fingertips, fingernails, and palms return. In one poem she writes, “Farewell, / my hand. / You were a loving / link / between me and the world.” Hands are signs of human connection for Domin, who reminds her readers that grasping is an evolutionary mechanism. Reaching out to hold on to something allows us to connect to others and the world around us. It is not surprising that she meditated on the part of the body that physically binds us to others in her search for stability and home. It is the hand that writes and touches.

Beyond the political reality of exile, Domin’s private life was one of separation and struggle, trapped in a marriage to a man who punished her for her talent. Domin’s husband, Erwin Palm, was resentful of her poetic gift. In her introduction Kafatou writes, “In her distress, Hilde had begun to write poems. Erwin, who claimed the role of poet for himself, resented her efforts and tried to discourage and even to forbid them.” In one poem, “Mower,” we are met with the iciness of their tortured intimacy:

Restless brilliance, blade

swung in a wide arc,

sickle of sun.I lie there like the meadow

and feel your knife,

mower,

irresistible and cold,

moving closer.And all the flowers

panic

in my heart.

Reading Domin’s poems one feels held by the elements of the natural world: sky, clouds, flowers, trees, grass, fields, meadows, feathers, bark, gulls, wind, dust, roses, and light appear again and again, capturing the experience of feeling at home for a moment, only to remember that it can be taken away:

I sit on a mountaintop

and have everything:

roof, walls,

bed, table

hot rainwater for my bath.

In another poem she counsels:

Don’t grow accustomed.

Don’t grow used to it.

A rose is a rose.

But a home

is not a home.

The possibility of exile, violence, insecurity, the loss of everything except one’s language, one’s mind—Domin’s poems reveal the inner need to establish security. When she and her husband made the decision to return to Germany after the war, they were not sure what they would find. The childhood house where Domin had grown up in Cologne appeared the same from the outside, with the same blossoming trees, but had been radically renovated on the inside. What was familiar was now foreign. In the newness of her old home she found she had forever lost a sense of belonging. There were only the things she carried, such as a wooden dove kept above her bed, and the work of writing. She called exile the experience of “portable wandering” and wrote, “I seek refuge in the smallest thing / the eternity of moss”:

Exile is never lost

you carry it with you

you slip inside

a folded labyrinth

a desert

it fits in your pocket.

Kafatou ends her collection with Domin’s most political poem, “Abel steh auf.” It feels as though there is an arc to her volume that builds toward a moment of rupture. In Burrows’s volume, the premise is the rupture, and the hope is that Domin will speak to the political violence of our world today.

Here is Kafatou’s translation:

Abel stand up

it must be replayed

it must be replayed every day

every day the answer must still be there before us

for the answer must be there

if you don’t stand up Abel

how will the answer

the only important answer

ever change . . .Abel stand up

for it to begin differently

between us allThe fires that are burning

the fire that burns on earth

will be the fire of Abeland what will trail the rockets

will be the fires of Abel.

It is tempting to read this poem literally: Abel, murdered by Cain, becomes the victim who must rise up. Or Abel, who is the victim, must rise up as a brother among men and show compassion for his brother Cain. Burrows writes in his introduction, “Through the anguish of loss and the bitterness of betrayal she came to see that only when we live responsibly, when we are here for each other—‘This Yes, I am here / I / your brother’—can we discover together what it means to be human.”

But there’s something too easy about Burrows’s interpretation. Domin is not offering a universal moral imperative for reckoning with the injustices of the world today caused by human hands, or how to be our brother’s keeper. One could read it as a Holocaust poem—the children of Abel as the Jewish people, daily afraid of German torment. But I think both readings are too safe for Domin. Too optimistic. Domin is not asking Abel to rise up today; she is returning to the scene of the crime and begging him to get up off the ground and to confront his brother. Because then, and only then in that moment, could there have been a different beginning. One where homesickness, longing, and the desire for return and flight were not the condition of human existence. And standing there, as if at the site of the slaying, Domin declares: I am a daughter of Abel.

The question is not just one of ending cycles of violence; it is a question about whether we would have ever been at home in the world at all—from the moment Cain was sentenced to a life of wandering. If Abel had risen, would he have forgiven his brother? Would he have struck him back? Would Abel have taken a match and burned Cain’s fields to the ground, or would he have embraced him?

Domin’s plea for Abel to stand up is a melancholy order. Since Cain was cast out, there has been no return. “I’m homesick for a country / where I’ve never been,” she writes. And eighteen years after Domin wrote the poem, she said, “Everything for me depends on this always-possible new beginning: the second chance. Which is provided for every person. That is the point of the poem ‘Abel Get Up’: a poem that is my ultimate word, and not only today.”

Gadamer’s naming Domin as the poet of return is a bit misleading. He meant that the poet is one who is always returning in language. But it is no simple return. Domin had literally returned to the country of her birth, but there she was always caught in the act of returning. What Domin knew from the time she started writing poems—perhaps the reason she began—was that while you might be able to go back physically, you can never go back all the way. From the moment she picked up her pen, she lived her life in flight, “among acrobats and birds.”

If exile is the human condition, then home is a place we can return to only in the mind. One gets the sense from Domin’s poems that to return finally is the same thing as to be buried. “You may have one spoon, / one rose, / maybe one heart / and, maybe, / one grave,” she writes.

Time might be made by men, but it is kept by nature, and Domin’s return, her second birth as a poet, began another clock, one for which she looked to the natural world to keep time. Or, as she put it, “I stepped into the air, / and it carried me.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Orpheus on the Lower East Side

Hart Crane’s name will forever be linked to Samuel Greenberg’s by a brilliant act of plagiarism, for the story of Greenberg’s posthumous manuscripts is almost as remarkable as the poetry itself.

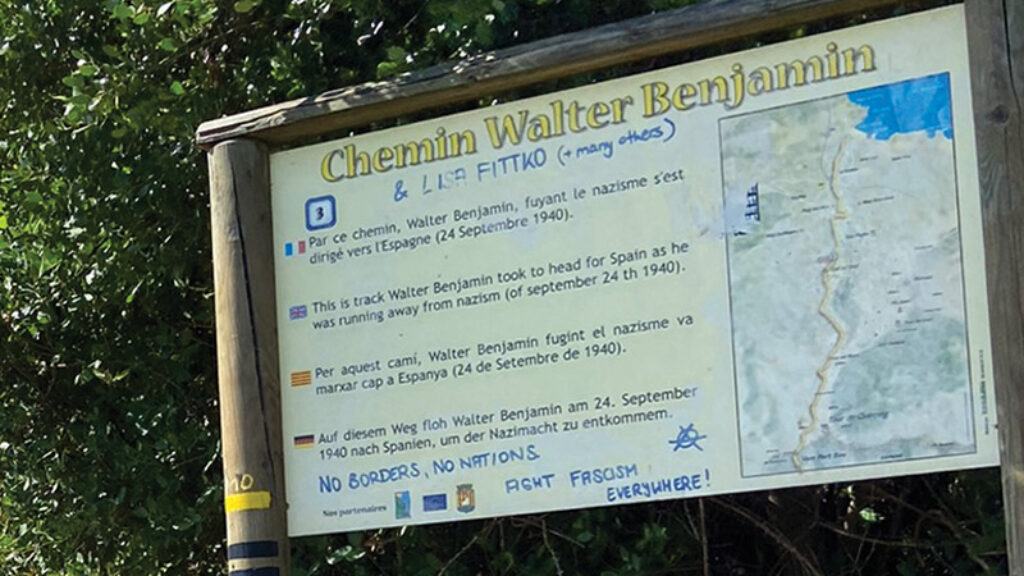

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

Intense Listening: The Poetry of Harvey Shapiro

Harvey Shapiro, who grew up in an observant Jewish family, was a connoisseur of distances and silences.

Moshkeleh the Thief

“The holiday is also sweet and dear because poor and dejected Jews toil hard, alas, and struggle, and just barely, in the nick of time, amid great trouble, angst and tribulations, bring in the holy holiday. Now, finally, they can rest and relax for eight days in a row.” A new translation of Sholem Aleichem by Curt Leviant.

LK

A fascinating article - I was unaware of Hilde Domin, and will look up her poetry, in German and in English. I particularly appreciated the sensitivity to translation, a current hobby horse of mine, so I also particularly regret that you did not (could not?) include the original German for some of the poems, especially the one that I assume is entitled "Über Uns," so that the reader could form an independent judgment of the relative merits of the contending translations.

Brad R

I thought that, based on the two Introductions, and the quality of the English translations as stand-alone poems without the German, it is possible to form a preference. But I, too, like publications where you can see poems side-by-side in translation and the native language.

BK

I'm so heartened and happy to learn of Hilde Domin from this article. In her own way and on so many levels, it comes across to this reader that Hilde Domin stood up. A path has been lit for others and a bridge provided to that history always to be remembered. Others will assuredly be greatly inspired to follow her out of the darkest places in making the world a better place, also on many levels.