Great Jews in Robes

Once ubiquitous, books celebrating the Jews’ attainments in one field or another have in recent decades lost their place in American Jewish culture. This is no doubt a consequence of the normalization of Jewish accomplishment (except in sports, which is the reason why the market for books about Jewish athletes is still strong). Among major institutions of American life, the NFL may be the only one in which Jews can still be considered pathbreakers.

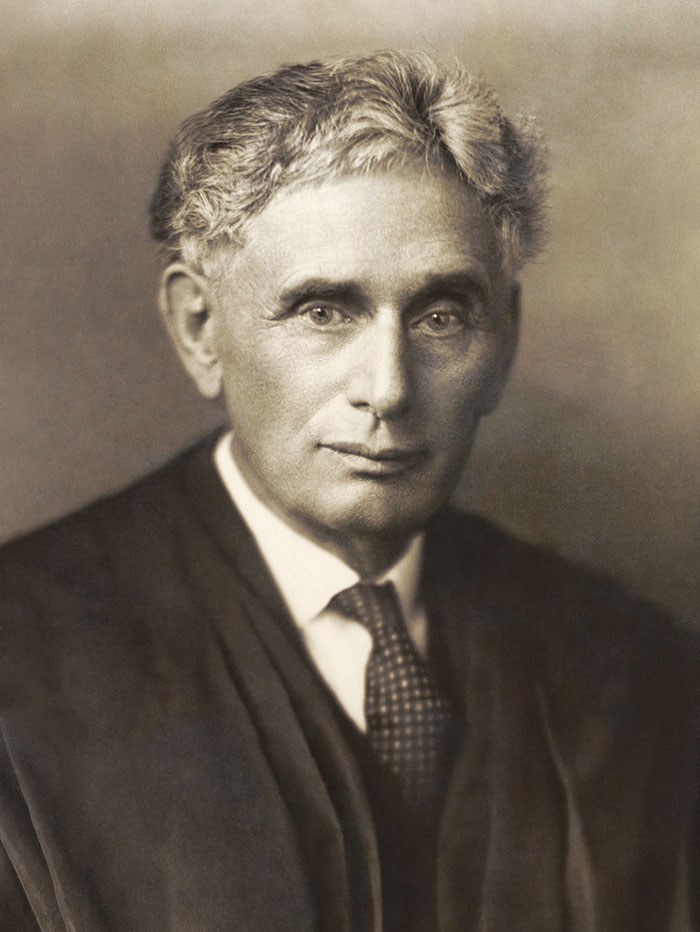

David Dalin’s Jewish Justices of the Supreme Court is thus something of a latecomer to the library of communal success, but it is nevertheless a very revealing study of the elevation of Jews to the pinnacles of American society as matters have unfolded on the United States’s highest judicial body. Just more than a century after Louis Dembitz Brandeis took his seat in 1916, defying vociferous and sometimes anti-Semitic opposition, hardly anyone finds it strange that the nine members of the court include three Jews. This means that Jews now enjoy a representation more than 15 times greater than their presence in the general population. If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court. Yet, as Dalin notes with astonishment, “for most of the country, [Garland’s] religious identity was utterly beside the point.”

How did this amazing state of affairs come about? One explanation is that Jews have a special affinity for the legal profession. Early in the book, Dalin quotes Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s version of this argument. In an introduction she wrote to a previous volume about Jewish justices, Ginsburg contends that:

There is an age-old connection between Judaism and law. For centuries, Jewish rabbis and scholars have studied, restudied and ceaselessly interpreted the Talmud, the body of Jewish law and tradition developed from the scriptures. . . . Jews prized the scholarship of judges and lawyers in their own tradition, and when anti-Semitic occupational restrictions were lifted, they were drawn to the learned professions of those countries in which they lived. Law figured prominently among those professions. . . . And, as it evolved in the United States, law also became a bulwark against the kind of oppression Jews had endured throughout history. So Jews in large numbers became lawyers in the United States, and some eventually became judges.

It is fair to say that Ginsburg is articulating perennial themes of the Jewish success literature rather than expressing a wholly original thought. Among the reasons that the argument recurs so frequently is that it allows Jews with only attenuated connections to traditional Judaism to sustain a sense of piety. The association of Judaism with law suggests that it doesn’t matter if Jews are ignorant of sacred texts or important rituals; so long as they’re experts in mens rea or Chevron deference, they can see themselves as successors of great rabbis. The elision of the distinction between divine and secular law helps Jews who cherish the idea of cultural continuity but have no interest in traditional learning to rationalize their indifference to religion.

This explanation for Jewish success in law is attractive, then, partly because it flatters secular Jews’ understanding of themselves. But that is not the only sort of vanity to which it appeals. It is also flattering to Jews’ conception of themselves as Americans. The story of Jewish lawyers and judges using their power and influence to fight oppression fits a broader narrative, in which American society moves ever closer to realizing justice for all its citizens. In this respect, Jews do not only get to present themselves as scions of an ancient lineage. At the same time, they can claim a position in the vanguard of social progress and thus see themselves as pioneers of the future.

Dalin praises Ginsburg’s explanation for Jews’ disproportionate role in American law as “aptly put.” But he also points out that Jews’ ascent from “rags to robes” was not so smooth as she suggests. “Jewish attorneys faced deeply entrenched antisemitism” as late as the 1950s, he notes, and even when they established their own successful practices, Jews were rarely admitted to the highest echelons of the profession. Dalin quotes the claim of the prominent attorney and Jewish communal leader Louis Marshall, who was considered for a Supreme Court vacancy by President Taft, that “it was only in exceptional cases that men of my faith were appointed to committees of the [New York City Bar] organization.”

Marshall’s description of discrimination against “men of my faith” is complicated by the fact that, at least at the highest levels, many of these men—and later women—had little faith of any kind. Dalin reports that four of the eight Jews who have sat on the Supreme Court grew up in Orthodox households and the rest had, with the exception of Brandeis, at least some Jewish education. But

Dalin finds that only one, Elena Kagan, the “product of a serious Jewish religious education who was raised in a religiously Conservative Jewish home” and “still considers herself a Conservative Jew,” has been observant during her time on the bench. Benjamin Cardozo apparently kept kosher but was not otherwise religiously active. And several other justices, including Ginsburg, Arthur Goldberg, and Brandeis himself, played significant roles in Jewish life without claiming any strong personal belief. For most of the Jews on the court, Jewishness has been more of an ethnic than a religious identity.

In this respect, the Jewish justices are similar to a majority of American Jews. That observation, however, raises questions about the price and consequences of Jewish success. Dalin points out that several justices developed a stronger Jewish identity after they took their places on the court, partly out of a sense of responsibility to the community. This did not prevent many of their families, however, from merging into the non-Jewish establishment. One of Brandeis’s daughters married the son of the social gospel theologian Walter Rauschenbusch, whom Brandeis himself welcomed, as Dalin notes, as “a ‘rare find’ and a welcome addition to his family.” Felix Frankfurter married the daughter of a Congregational minister, a union that produced no children. Stephen Breyer is married to an Anglican and has a daughter who is an Episcopal priest.

My intention is not to censure others’ domestic lives. Rather, it is to point out the way the curriculum vitae of Jewish Supreme Court justices mirrors the broader trajectory of American Jewry. The process begins with the rejection of strictures that seem antiquated or oppressive in a new country. It continues on to the stage of extraordinary accomplishment, as flexible attitudes toward tradition and relatively weak patterns of anti-Semitic discrimination allow individual Jews to make the most of their talents. The result is the anointment of symbolic Jewish leaders who are, in many ways, not very Jewish. Finally, the descendants of these leaders, recognizing that they are not different in any substantial way from the rest of the American elite, merge seamlessly into it.

If this pattern is typically presented as a success story, it can also be depicted as a crisis. The central problem of American Jews today is not oppression, but voluntary elimination through assimilation and intermarriage. There is something tragic as well as inspiring, then, about the biographies and social history that Dalin sketches. By attaching Jewish identity to professional accomplishment, highly successful Jews can inadvertently promote its disappearance.

The tension between achievements of individual American Jews and the communal future of Jews in America is one reason to regard this book as a somewhat equivocal contribution to the success literature. Another is the light Dalin shines on the causes of Jews’ elevation to the Supreme Court—and their conduct once they arrive there. The conventional narrative attributes this outcome to their undoubted talents and commitment to justice as they saw it. But Dalin also reminds readers that appointment to the court is a political process. Jews have received their appointments because they have been useful to the presidents who selected them.

It is not just a matter of filling what used to be considered the court’s “Jewish seat.” Before joining the court, Frankfurter, Goldberg, and Abe Fortas were noted as party operatives and presidential intimates as well as for their legal abilities. This is not inherently a criticism; it is only recently that experience on the federal bench or at least in the Justice Department has become a prerequisite for appointment. But it is worth remembering that the careers of many Jewish justices were based not only on juridical skill, but also on political loyalty and talent for cultivating relationships with the powerful. Abe Fortas, for instance, earned Lyndon Johnson’s total confidence by devising the legal strategy that helped Johnson fend off Coke Stevenson’s challenge to his pivotal but highly questionable 87-vote victory in the Democratic primary in the 1948 Texas Senate race. A decade later, when “George Parr, the notoriously corrupt Democratic political boss of Duval County, Texas, who had helped ‘produce’ Johnson’s extra votes to secure his Senate victory, was later convicted of mail fraud, Johnson engaged Fortas on Parr’s behalf.” Johnson was clearly fearful that Parr would be tempted to spill the beans about what happened in 1948. “Fortas, a master legal technician, took Parr’s appeal, pro bono, to the Supreme Court, where he won a reversal of the conviction on a technicality.”

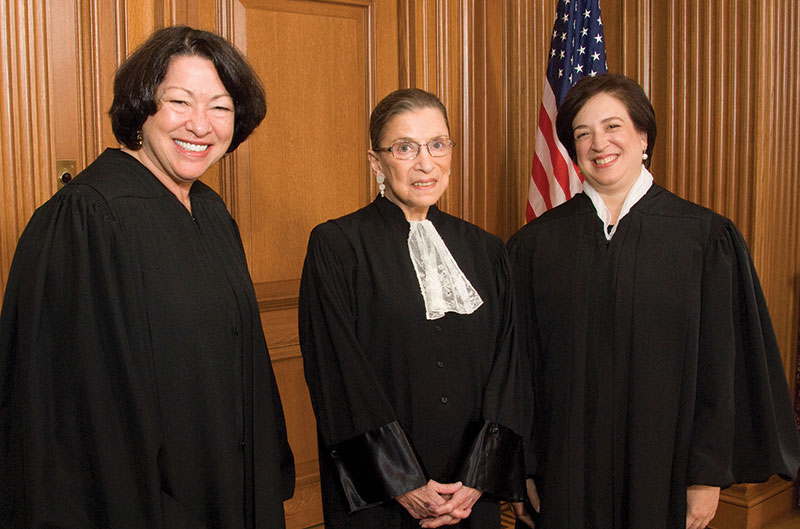

Kagan’s investiture ceremony. (Photo by Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.)

Even Brandeis, whose pioneering role on the court and leadership of the American Zionist movement has given him a reputation as a kind of Jewish saint, appears here in a less flattering light. Although he points out that “Brandeis was continuing a Supreme Court tradition of justices engaging in extrajudicial political activity stretching back to the republic’s beginning,” Dalin acknowledges that Brandeis’s role as an advisor to Wilson and Roosevelt on questions of policy went beyond even the more flexible boundaries of the time. In perhaps the most egregious example, Brandeis met secretly in 1935 with the New Deal insiders and Frankfurter protégés Benjamin Cohen and Thomas Corcoran after the court’s decision in Schechter Poultry Company, which effectively rendered the National Recovery Administration (NRA) unconstitutional. He then encouraged Cohen and Corcoran to tell Frankfurter to advise Roosevelt to find a new strategy for the New Deal. This was not entirely an act of fealty to the administration: Brandeis had joined Cardozo and all the other justices in rejecting the NRA’s regulation of the poultry business, which unintentionally complicated the sale of kosher chickens. Nevertheless, he colluded with the administration and future colleague on the court to find a way around his own ruling.

The problem was not Brandeis’s personal honesty, but his conception of the law as a tool for the achievement of political and social goals. It is not unreasonable to fear that this instrumental attitude to jurisprudence really does threaten to replace the rule of law with the rule of judges. The same risk is implicit in Brandeis’s greatest innovation, the so-called Brandeis Brief, the prototype of which he submitted to the Supreme Court as a litigator when he was arguing Muller v. Oregon, which considered the constitutionality of laws restricting working hours for women. Prepared by Brandeis’s sister-in-law Josephine Clara Goldmark, the brief combined legal analysis with the findings of social science. The point was that judges had to consider the real-world consequences of their decisions as well as traditional considerations such as the statutory text and existing precedents:

While devoting only two pages of his brief to the legal precedents for regulating women’s work hours, Brandeis spent a full 110 pages on social science data and analysis in support of his legal argument. The approach worked: the majority of the court, while hostile to labor legislation generally, upheld the Oregon law and specifically credited Brandeis and his sociological approach in rendering its decision.

Admirers of this approach might point beyond its impact here to the court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education as a demonstration of its value. It would be well to remember, however, that ostensibly scientific arguments were also used to justify the court’s endorsement of compulsory sterilization in Buck v. Bell. Brandeis not only joined the decision, but described it as showing how states could legitimately “meet modern conditions by regulations which a century ago, or even half a century ago, probably would have been rejected as arbitrary and oppressive,” as quoted in David E. Bernstein’s Rehabilitating Lochner. There is no reason to think deference to science—particularly the unavoidably ambiguous social sciences—provides a more reliable path toward securing the promises of the Constitution than does the text of the Constitution or the interpretive traditions that appeal to it. Brandeis’s critics were not wrong to worry about his influence on American jurisprudence.

Jewish Justices of the Supreme Court is a narrative history rather than a critical analysis. Its accessible style, abundance of illuminating anecdotes, and helpful synthesis of an extensive scholarly literature will make it valuable to historians of the American Jewish experience. Yet I wonder whether the book’s emphasis on its subjects as Jews is anachronistic. It concludes, after all, with the paradoxical proposition, in which “it would seem unimaginable to many, within the Jewish community and without, that there could be a Supreme Court without a Jewish justice,” yet the justices’ Jewishness is simply not very important. In many respects, this is an achievement worth celebrating. But it raises the question of whether it will be possible to write a similar volume in another century.

Suggested Reading

A Dashing Medievalist

Ernst Katorowicz had great courage and old-world personal charm—his Berkeley students were mesmerized by him.

Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

A new batch of Israeli fantasy books may not contain Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

How Jews Were Modern

What’s a nice Jewish boy doing making bronze statues of tsars? And does it count as Jewish culture? Ahad Ha’am wanted to know and the Posen Foundation’s ambitious new survey raises the question afresh.

A Stone for His Slingshot

In 1948 screenwriter Ben Hecht lectured “a thousand bookies, ex-prize fighters, gamblers, jockeys, touts,” and gangsters on the burdens and responsibilities of Jewish history. The night at Slapsy Maxie’s was a big success, but the speech was lost, until now.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In