A Dashing Medievalist

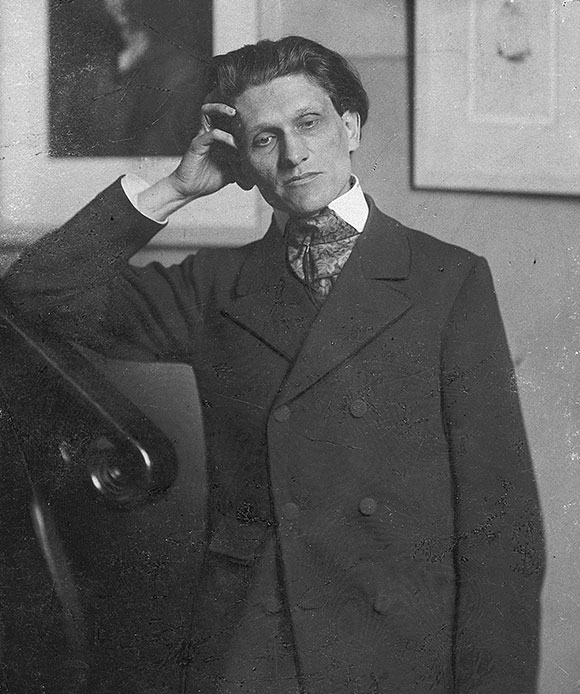

In 1922, the Hartwig Kantorowicz firm ran an animated advertisement of “two men having an argument until a bottle of liqueur miraculously appears, golden liquid then flows down their throats: they smile and make up; then a caption appears: ‘Kantorowicz: Famed throughout the world.’” While this has long ceased to be the case, the most accomplished scion of the Jewish family that launched the company, the historian Ernst Kantorowicz, has retained more than a shadow of what was once a towering scholarly reputation. His 1957 classic The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology, which can be described as a fantastically erudite commentary on the saying “the king is dead, long live the king,” is still in print and on the reading lists (if not the bedside tables) of aspiring medievalists. Now, thanks to the appearance of Robert E. Lerner’s massive, deeply researched, and fascinating biography, EKa—as Kantorowicz was known to his friends and is identified throughout the book—is more famous than he has been since his death in 1963. Or at least since Norman Cantor’s cartoonish portrait of him as the ideological “twin” of his friend and fellow medievalist Percy Ernst Schramm, who joined the Nazi Party and spent World War II as the official staff historian of the German High Command.

Lerner begins his book with an account of EKa’s early life in the city of Poznan, at the time located in Germany. (It became part of Poland after World War II.) His family was wealthy, and his friends and acquaintances included many aristocrats. At home, the thoroughly assimilated Kantorowiczes celebrated Christmas but not Hanukkah, Easter but not Passover. In World War I, EKa fought in the German army first on the Western Front, later in Turkey. He received several medals (including the Iron Cross) for showing extraordinary bravery and after the war joined the paramilitary Freikorps, fighting mainly against Polish intruders as well as communists. These units were in various ways precursors of the Nazis, and the presence of a Jew in their ranks was highly unusual, to say no more.

After leaving the Freikorps, EKa studied at Heidelberg, which was at the time still the university with the greatest reputation in German literature and history. Through one of his teachers, Friedrich Gundolf, a major figure in German literary life at the time, he became acquainted with the charismatic poet Stefan George. EKa soon became a member of George’s inner circle. These young intellectuals subordinated themselves to “The Master” and considered themselves members of the “Secret Germany” that would one day become ascendant. As I noted long ago in a book that discussed this odd, important cultural phenomenon, George wrote “about the need for a new nobility . . . about the Führer with his völkische banner who will lead his followers to the future Reich through storm and grisly portents, and so forth.” Despite the genuinely ominous ring of these words, neither George nor his acolytes were typical German nationalist extremists. In a famous short poem describing his followers, George depicted them as a small elite group, apart from the crowd, making its own way under the banner of Hellas.

As is widely known, the George circle attracted many Jewish artists and intellectuals (Gundolf, originally Gundelfinger, was himself Jewish), but it is not easy to explain this attraction, even in retrospect. Even Lerner in this wide-ranging and learned biography does not quite manage to solve the riddle. How could a man of such great historical knowledge and such wide life experience as EKa be so grievously mistaken in his political judgment?

I belong to a considerably younger generation than George and his circle, but among my friends and acquaintances were some who had been close to them. For instance, my academic colleague Klaus Mehnert’s older brother Frank had been Stefan George’s secretary and valet. I remember a long conversation with Klaus as we walked the streets of Moscow. He had just returned from China and was trying to convince me that Mao had come close to changing human nature in his country. When I expressed grave doubts, he said, “Walter, I also doubted it, but believe me, I have seen it, and chances are that he will succeed.” The poetry of this circle was frequently exquisite, but their political judgment was not.

Eka became an instant celebrity in 1927 with the publication of his massive popular biography of Frederick II, the famous 13th-century emperor of Germany and Italy. The book idealized the Hohenstaufen (the German imperial family) and Frederick II in particular, who Kantorowicz described as “the fiery lord of the beginning, the seducer, beguiler, the radiant, merry. The ever-young, the severely powerful judge, the scholar and wise man, the helmeted warrior leading the round-dance of the muses.” The Neue Freie Presse of Vienna said of Kantorowicz’s book that “One reads it as if it were the most suspenseful novel. The brilliant, artful-hot-blooded style of the author identifies him as a member of the circle of Stefan George and Gundolf. . . . Breath-taking.” As Lerner notes, it was also a celebration of authoritarianism and a call to the German people to again make itself worthy of such a leader and “redeem” Frederick. Göring is said to have presented the book to Mussolini, and Percy Schramm said that Hitler read it twice, though Lerner quite plausibly doubts the claim.

But the book was also a genuine marvel of deep scholarship and creative synthesis, and on its merit the 31-year-old author soon leapfrogged into an honorary position as a history professor at the new University of Frankfurt. The position came without a salary—but he didn’t need one, not at first. Things changed, however, in 1931, when his family’s firm collapsed. Shorn of his inherited wealth, reliant solely on his significant but limited royalties from the biography, EKa might have found himself in real trouble, but “fortune smiled when a well-paid full-professional position became available at Frankfurt” in February 1932.

A year later, Hitler came to power. In April, the Nazis took control of Frankfurt University, and the University Senate quickly suggested that Kantorowicz take an immediate leave of absence for the sake of “avoiding disruptions of his classes.” He drafted a bold response, which Lerner describes:

Instead of asking for a leave, he astonishingly requested suspension of his professorship for the indefinite future, albeit with continuing pay. The grounds were not that he agreed his classes were likely to be disrupted, for he considered his “national” orientation to be well known. But he maintained that the recent anti-Semitic actions made it impossible for him to demonstrate his national commitment without seeming to curry favor by continuing to teach.

“What are we to say?” Lerner asks. “If we replace the term ‘national’ with ‘patriotic,’ his statement becomes somewhat more palatable. But nothing can rescue the fact that the letter refers positively to the ‘again nationally oriented Germany’ . . . and then goes so far as to maintain that the author’s ‘fundamentally positive view toward a nationally governed Reich’” had not been “shaken” by the latest Nazi actions. On the other hand, the draft, which Kantorowicz preserved in his papers, and the subsequent letter go on to indict recent anti-Semitic measures of the Nazis and state that “so long as the fact of having Jewish blood in one’s veins presumes a defect in one’s beliefs . . . I consider it inappropriate to hold a public office.” And yet, on the same day, he also sent a letter not only describing but apparently exaggerating his activity with the ultra-nationalist Freikorps after World War I. The upshot was that he asked for and was granted a leave of absence for the summer, from which he never returned. Nevertheless, he continued to receive his pension for many years, thanks to the emeritus status (which he found comical) that went with his forced retirement.

In his surprisingly popular 1991 work on 20th-century medievalists, Inventing the Middle Ages, the aforementioned Norman Cantor alleged much worse than this. For him, “Kantorowicz’s Nazi credentials were impeccable on every count except his race,” and he made much of the nationalist rhetoric in EKa’s letters to the university. But this was merely the customary style, reflecting the spirit of the times. Any deviation from it would have been considered almost hostile and certainly ineffective. Cantor also charged that Kantorowicz actually stayed on in Germany after 1933 under the protection of “Nazi bigshots” he hoped would eventually help him return to his position at Frankfurt. Cantor suggested that Kantorowicz thought “militant anti-Semitism [was] just a vulgar intermediary instrument for the Nazis [that] would burn away; then he would get his suitable reward and eminence in the Hitlerian regime.” This attack, which came in a chapter titled “The Nazi Twins,” created a medium-sized intellectual scandal when it was published, with letters to the New York Review of Books and so on. His accusations, as Lerner patiently shows, were almost entirely unwarranted.

In 1934, EKa visited Oxford, where he met the distinguished classicist Sir Maurice Bowra who, according to Lerner, became his sometime lover and his best friend for life (Kantorowicz had relationships with both men and women). If they were so close, it is a little difficult to understand why Bowra, one of the most influential figures in Oxford and eventually a vice chancellor of the university, did not find it possible to help him to stay in England, instead of returning to Germany after a year and a half. In the absence of any such opportunity in England, EKa focused his efforts on America and was lucky enough to find, in the nick of time, a temporary position at the University of California, Berkeley, where he began teaching in the winter of 1939.

In addition to his intellectual brilliance, EKa had great courage and old-world personal charm—his Berkeley students were almost as mesmerized by him as he had been by Stefan George—but these qualities sometimes led him astray. He seems to have realized in later years that his glorification of Frederick II went too far. He is reported to have said of his Frederick biography after World War II that, “The man who wrote that book has died long ago,” and he did not permit it to be reprinted in his lifetime. But the person who had allegedly died seems very close to the EKa who survived, and one looks more or less in vain among his writings for notice of this earlier self’s death.

Some, including Lerner, have seen his conduct at the end of a decade of highly successful teaching at Berkeley as evidence of a basic change in his political stance. Faced with the demand to sign an oath of loyalty swearing that he had never been a communist, he relinquished his position as a tenured professor at the University of California. In fact, as he remarked to a colleague, he had shot communists in the Freikorps, but he found the oath stupid and demeaning. At a public university meeting at which the oath was debated, Kantorowicz said:

History shows that it never pays to yield to the impact of the momentary hysteria . . . It is a typical expedient of demagogues to bring the most loyal citizens, and only the loyal ones, into a conflict of conscience by branding non conformists as un-Athenian, un-English, un-German . . . It is a shameful and undignified action, it is an affront and a violation of both human sovereignty and professional dignity that the Regents of this University have dared to bully the bearer of this gown into a situation in which . . . he is compelled to give up either his tenure, together with his freedom of judgment, his human dignity and his responsible sovereignty as a scholar.

In the end, he gave up his tenure. This was an act of principle, but it was also to some extent an expression of EKa’s vanity. He was a courageous man, but he also liked his courage to be noted. It is possible that there had been a fundamental change in his political attitudes, but this we cannot know. If there was such a change, was it caused when he first heard about the death of his mother and his sister after their deportation from Germany to Theresienstadt or earlier? Again, we do not know. His correspondence is strikingly silent with regard to these matters.

Expelled from Berkeley, EKa had no trouble landing on his feet at the recently established Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, whose founder was one of his admirers. It was there, in the 1950s, that he completed The King’s Two Bodies. It was also there, in 1961, that Robert Lerner, then a 21-year-old graduate student, briefly met his future biographical subject at a faculty cocktail party, nattily dressed with a presence that “announced ‘great man’.”

Not being a medievalist, my long-time interest in this strange and fascinating character arose not from his path-breaking studies, but much more from an interest in the strange ideological contortions of a German intellectual of Jewish origin trying hard (not always unsuccessfully) to escape his background and his past. In this context, it must be said that EKa never made a complete break with his Jewishness. He seems to have realized that it would be undignified and even cowardly to escape from what became in the Nazi era an attacked, beleaguered community. He did not really want to remain a member, but he was not a deserter. This kind of attitude did exist among certain groups of German Jewry up to and including the early Hitler years.

Lerner’s biography is worthy of great praise, and it is very unlikely that it will ever be superseded. He has evidently read all of the available material and interviewed many of EKa’s contemporaries at Berkeley and Princeton. If it does not quite offer answers to all of our questions about EKa, it is not really Lerner’s fault. Kantorowicz was a charming man of immense talent, but he also took care to conceal much of his inner life. He was brave and brilliant but at the same time, a very slippery customer.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Apples, Honey, and Articles

A compilation of 10 favorites from the JRB archives that follow the arc of the fall holidays, from Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, to Sukkot and Simchat Torah.

Doron Rabinovici and the Crisis of European Jewish Identity

To live in Vienna as a Jew is also to be reminded that those who perpetrated the Shoah were defeated yet, unlike the victims, were able to resume their lives afterwards.

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

Animal Foible

The author of Life of Pi trivializes the Holocaust.

gwhepner

MAKING A TABULA RASA OF ONE'S LIFE WITH DISTORTED IMAGINATION

“The man who wrote that book died very long ago,”

Ernst Kantorowicz declared regarding his great book on Frederic the Second,

the grandson of Frederic Barbarossa,

trying to make a tabula rasa

of his own life, which, with a distorted imagination that was fecund

brought him to Berkeley, where such people often go.

[email protected]