Kidnapping History

In January 2018, the Israeli press reported the dramatic reunification of Varda Fuchs with her biological sister Ofra Mazor. A DNA test confirmed their relationship, and more than one newspaper proclaimed this to be the smoking gun that proved the truth of the longstanding accusations that thousands of Yemenite and Mizrahi babies had been taken from their homes and transferred to childless Ashkenazi families like the Fuchs family in the early 1950s.

In February 2019, the New York Times published a long article by Malin Fezehai called “The Disappeared Children of Israel,” which highlighted the story of Varda Fuchs in its account of the Yemenite Children Affair. According to the article, Varda’s biological mother, Yochevet, who is now deceased, was able to breastfeed her baby only once after giving birth to her in an Israeli hospital in 1950. Soon afterward, the nurses told her that her newborn daughter had died. “Ms. Mazor’s mother did not believe them and had her husband demand their child back. He was never given the child.”

It was a moving—and damning—story, and the Times did not hesitate to draw the conclusion that the Zionist project of immigrant absorption was fatally flawed by Ashkenazi elitism and outright racism. The article quoted Naama Katiee as comparing the Yemenite case to the forcible removal of Aboriginal children from their homes in Australia and Indigenous children in Canada around the same time. Katiee and other activists allege a deliberate, or at least de facto, government policy of cultural theft in the most literal sense: kidnapping.

In 2016, two years before Varda Fuchs’s DNA test, the Israeli government, responding to public pressure, declassified almost all the material collected by different commissions of inquiry about the Yemenite Children Affair over a period of decades, a total of more than four hundred thousand documents from the State Archives. Since everything was scanned and uploaded to the Internet, independent researchers, bloggers, and academics have been able to scrutinize in detail the cases of children who had disappeared, including Varda Fuchs. The blogger Nona Dulberg (a pseudonym) posted her discoveries on Facebook, and they made their way into the Israeli media, but not the Times.

Among other things, Dulberg discovered that Fuchs’s biological mother, Yochevet, was seventeen years old and unmarried when she became pregnant. When she went into labor, she was admitted to the hospital under the false name of Esther Arazi. Two days after giving birth, Yochevet fled the hospital, leaving her daughter behind. Five days later, an article about her flight in the local newspaper Haboker urged the mother to return to her baby. More than six months after that, the Department of Social Work in the Tel Aviv municipality published an ad in three newspapers declaring that if Esther Arazi did not reclaim her baby, she would be put up for adoption within thirty days. When a month had passed, the baby was turned over to the Fuchses, a childless couple of German Jewish origin.

Later, Yochevet and her boyfriend, Shalom Hayun, married. They told their four subsequent children that they had another sister, but they never complained to any of the state commission inquiries that she had been kidnapped by hospital workers. Varda Fuchs’s story was tragic, but it was not the smoking gun of the Yemenite Children Affair for which activists have been searching for more than half a century.

The New York Times had thirteen months to get its facts straight but instead chose “alternative facts.” This type of inaccurate reporting about the case of the supposedly stolen Yemenite children has become the norm in most Israeli media and for some Israeli academics driven by social justice activism. And yet, the facts are largely available. It is, in fact, one of the most investigated episodes in Israeli history. There have been four independent commissions that examined the accusations of child theft.

While the Times article pegged the tally of missing babies and toddlers at 1,000, some activists have alleged that the number was as high as 2,050 or even 4,500. The source of these latter two figures is Nathan Shifris, whose book Yaldi halach le-an? Parshat yaldei teiman: ha-chatifah ve-ha-hachchashah (Where Has My Child Gone? The Kidnapped Yemenite Babies Affair: The Abduction and Its Denial) theorized that the Yemenite babies were stolen by the medical crews under the orders of the political establishment, especially during the years 1949–1954. Shifris is not the first to come up with these accusations, but his role in spreading them has been outsized, for he is not merely a scholar of the subject but one of the major players in the controversy since the early 1990s. His more recent collection of academic studies on the subject, Yeladim shel ha-lev: hebetim chadashim be-cheker parshat yaldei Teiman (Children of the Heart: New Aspects of Research on the Yemenite Children Affair), which he edited with Bar-Ilan anthropologist Tova Gamliel, pursues these allegations, though, as we shall see, some of its chapters also present evidence that undermines them.

Is the Yemenite Children Affair the result of difficult circumstances, bureaucratic inefficiency, and human frailty, or—as Shifris has spent an extraordinarily complicated and problematic career alleging—was there a terrible government conspiracy at work?

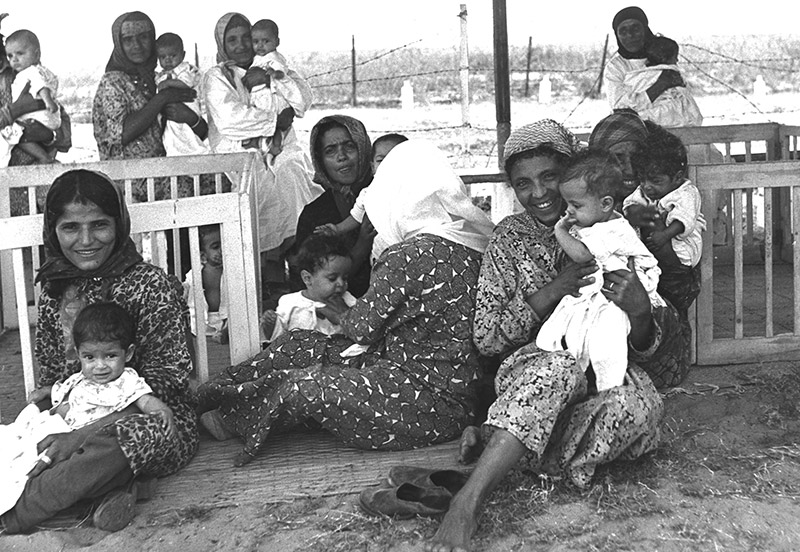

Between June 1949 and September 1950, almost the entire Yemenite Jewish community arrived in Israel, rescued from local marauders, starvation, and disease in what was called “Operation Magic Carpet.” About fifty thousand people came,

including around five thousand babies and toddlers. Needless to say, they were part of an extraordinary wave of immigrants to Israel in those early years of the state. Between 1948 and 1954, Israel absorbed 687,000 immigrants: Holocaust survivors from displaced persons camps in Europe and Jews from Romania and Iraq in addition to those from Yemen. However, the Yemenites were unique in some respects. They spoke neither modern Hebrew nor any European language, had little experience with modern government and medicine, and had been culturally isolated in other ways. They also arrived in very poor health: polio, tuberculosis, and typhoid were rampant among them. Consequently, they were housed in deserted British military camps and tents and kept apart from other immigrants.

Of the sixteen essays in Children of the Heart, only three are directly about the affair itself. The rest are on its cultural, sociological, and political context and consequences. Most of the contributors take at face value some version of the claim that large-scale institutional kidnapping took place and condemn the alleged Israeli racism toward the Yemenites, which underwrote the crime. Nonetheless, some of their articles paint a more complex picture.

For instance, Esther Meir-Glitzenstein of Ben-Gurion University describes how the first phase in the Yemenites’ absorption centered on their physical rehabilitation. They needed food rich with protein to overcome hunger and malnutrition and expert medical care to treat malaria, tropical ulcers, and eye diseases, among many other ailments. Although the new state had suffered from a series of financial crises and there was a shortage of produce, the Yemenite immigrants actually received better food than most other Israelis because of their serious health conditions. On the other hand, 1950 was one of the hardest winters in Israeli history, and the Yemenite immigrants had to endure it in tent camps. According to Haim Zadok, a Jewish Agency employee cited by Meir-Glitzenstein, “The death toll was high in the early weeks, and we had the horrible experience of discovering dead people in their tents.”

Earlier that fall, on September 20, 1949, Moshe Shapira, Minister of Health, had already lamented that there were three thousand babies and toddlers in serious condition. In an effort to alleviate their health problems and to protect these babies from the harsh conditions in the camps, the state opened infant infirmaries, or Babies’ Homes (Batei Tinokot), for them. Their mothers were able to visit the babies there and to breastfeed them. However, in a morally and politically disastrous decision, babies in need of immediate hospitalization were taken to nearby hospitals without the parents receiving any notification. Even more unforgivably, if the baby died, he or she was immediately buried without the parents’ participation.

Inevitably, this aroused the suspicions of the immigrants and led many parents to hide their children and refuse to transfer them to Batei Tinokot. The thoughtless exclusion of the parents from their children’s burials is unacceptable and haunts Israeli society until today. No parent comes to terms with the death of a child, certainly not one taken away and buried anonymously.This would later nourish conspiracy theories that the babies had not really died at all and had been turned over to others. And yet, to be fair, one must remember Israel’s limited resources and the staggering logistical burdens it faced in those years, as it absorbed about seven hundred thousand immigrants. The immigrants had been saved from a perilous situation in Yemen, and the state was doing its imperfect best to integrate them into the country.

Bar-Ilan historian Dov Levitan, who pioneered the academic study of the Yemenite Children Affair, states in his contribution that in Yemen itself, the mortality rate for newborns among the general population was above 50 percent. Consequently, the immigrant parents were initially prepared to believe the medical crews that reported the deaths of their babies. In any case, the parents had limited ability to visit their hospitalized children; they did not know how to travel in the new land, and even if they did, they did not have the money to pay for buses. Also, in many cases, the children’s names were incorrectly transcribed at the hospitals, and the medical crews often had difficulty finding a child’s parents, who might have moved to a different camp during long periods of hospitalization. Levitan concludes that the shock of the transition to the modern world immobilized the parents.

Levitan also demonstrates that already in 1950, the Israeli police had learned of the disappearance of some Yemenite children and were investigating at least twenty-eight cases. Some of these cases were covered in the newspapers and discussed in the Knesset. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Health and the Jewish Agency showed no interest in this painful issue, and it was left to fester for almost two decades.

Why was there no investigation in the 1950s when the complaints were still fresh? Perhaps it was because at that time, as Levitan notes, the immigrants had little political influence. Besides, in 1949 and 1950, after Yemenite children had been assigned to secular schools, the Orthodox parties virulently objected to their forced secularization, producing a commission of inquiry and ultimately leading to the fall of Israel’s first government. The authorities, Levitan concludes, did not want to risk yet another political land mine.

The first national commission to investigate allegations of government-sponsored kidnapping was established only in 1967, after several families had the deeply unsettling experience of receiving army conscription orders addressed to their dead children. This led to desperate suspicions that perhaps their children had never died. The Bahalul-Minkovsky Commission was created and examined 342 cases. The commission concluded that 316 babies had died, and four other babies were found to have lived in foster homes or been adopted. But the fate of twenty-two of the children remained unclear due to missing documents. This appeared to put the matter to rest—but not for long.

Thirteen years later, in 1980, Moshe Schonfeld, a haredi anti-Zionist journalist, published Genocide in the Holy Land, in which he accused the State of Israel of having conducted a physical and spiritual program of genocide against the Yemenite children. Rabbi Meir Kahane, head of the Jewish Defense League in the United States and head of the Anti-Arab Kach movement in Israel, picked up this theme, and in 1986, Kach published a book based on Schonfeld’s work. Kahane, who was a Knesset member at that time, cited this account at the Knesset’s podium and called for the establishment of a new commission of inquiry.

These accusations eventually led to the creation of the Shalgi Commission in 1988 and to a new round of allegations from Yemenite families. The committee investigated 505 cases, 301 of which had not been investigated by the previous commission. Of the new cases, the commission concluded in 1994 that 236 children had died and the fate of 65 others could not be determined. The committee also examined about ten thousand adoption cases from the establishment of the state until 1993 to look for any illegal or suspicious adoptions of Yemenite babies. It uncovered no new information.

In the early 1990s, however, Rabbi Uzi Meshulam, a mystical fantasist who believed, among other things, that the Yemenites were the purest Jews of all and that the Ashkenazim were mere European fakers, began preaching that the Yemenite children had been abducted and sold to Ashkenazi couples. By exposing the conspiracy, Meshulam believed, he could hasten the coming of the messiah (and that he was a good candidate for the role). Meshulam attracted a group of about one hundred followers. One of them was a young Nathan Shifris, who had just finished his military service as a low-ranking intelligence officer in the IDF. In 1994, Shifris helped Meshulam write an open letter to the Knesset claiming that he held evidence that 4,500 kidnapped Yemenite children had been sold not only to Ashkenazi families in Israel and the US but to Christian monasteries—and for use in medical experiments. Unsurprisingly, this letter was largely ignored.

Shortly afterward, Meshulam fell into a dispute with his neighbor in the town of Yahud over a sewage repair, which quickly deteriorated into an armed confrontation. When the police arrived, Meshulam and his followers barricaded themselves in his house and demanded that the State of Israel establish an independent State Commission of Inquiry into the Yemenite Children Affair. After a forty-seven-day siege, the police finally tricked Meshulam into leaving the building and arrested him. Meshulam’s followers in the compound were asked to put down their arms, but one of them started shooting at a police helicopter and was killed by a sniper. Although Meshulam threatened mass suicide, the episode did not end like the siege of the Branch Davidians two years earlier in Waco, Texas, as many had feared. Meshulam was eventually sentenced to eight years in prison. Nathan Shifris was sentenced to four years.

Despite his unhinged claims and evident delusions of grandeur, Meshulam’s accusation that all previous inquiries had whitewashed the true story led in 1995 to the establishment by the State of Israel of a new, open-doors State Commission of Inquiry to study the Yemenite Children Affair, chaired by Supreme Court judge Yehuda Cohen and, later, Supreme Court judge Yaacov Kedmi. The new commission invited Meshulam to testify, but he refused to do so unless his testimony was aired on live TV, and he did not end up testifying.

The Kedmi-Cohen Commission examined more than eight hundred cases, in 733 of which it determined that the children had actually died. It left 56 cases entirely unresolved and acknowledged that it was possible that these children were handed over for adoption by individual local social workers, though not as part of an official policy. Nevertheless, it did not find any evidence of a single such adoption, and none has been found since. The commission unequivocally rejected claims of a government plot to take children away from Yemenite immigrants.

During the 2010s, the Yemenite Children Affair returned to Israeli public discourse with the formation of two advocacy groups, Amram and Forum Achai, both of whom demanded a new investigation and compensation for Yemenite families. In 2016, Prime Minister Netanyahu tasked minister Tzachi Hanegbi, a Likud member of Yemenite origin, with reassessing all the evidence. Hanegbi was unconvinced by the previous studies and quickly told Israeli TV, “They took the children and gave them away. I don’t know where,” saying that hundreds had been kidnapped.

The Netanyahu government decided to declassify all the documents relating to the affair from the State Archives, and the Knesset ordered a new investigation headed by Nurit Koren, a Likud member who, like Netanyahu and Hanegbi, had no sympathy for the Labor Party–led establishment of the early 1950s. Koren made it unmistakable that she believed that the alleged kidnappings had indeed occurred, and she partnered with DNA testing company MyHeritage to offer 1200 free tests. The tests did not uncover any kidnapped Yemenite children who had grown up with Ashkenazi families.

Koren’s investigation never issued a final report, but all the commissions of inquiry came to similar conclusions on the basis of the 1,053 total cases that they examined. Most of the babies died, and the proof of their deaths included death certificates signed by doctors, burial records, ambulance records, and more. In about 70 cases, the evidence is missing, but the most reasonable assumption is that, tragically, these babies died as well.

In the years after being released from prison, Nathan Shifris completed his PhD in Jewish history with a dissertation on the Jewish Enlightenment in nineteenth-century Galicia; however, his true career has been pursuing and justifying the conspiracy theory of his erstwhile mentor Uzi Meshulam. In Where Has My Child Gone? Shifris simply ignores the mountain of documents accumulated by the different investigations because, since for him, all the official records from the time should be treated as prima facie suspicious. Indeed, he regards the death certificates as clear evidence not of the tragic deaths of malnourished, sickly babies but of a massive government plot. Instead, he chooses to base his theory solely on the testimonies of family members given to the Kedmi-Cohen Commission in 1995, more than four decades after the events in question. According to Shifris, the testimony of hundreds of parents was eerily similar: “Children were described as healthy or having minor issues” when taken from their parents to the Beit Tinokot. According to Shifris, these Babies’ Homes did not serve a medical purpose. Instead, they created a barrier between parents and their children; the second step was to send the babies to hospitals, not because of their health, but to complete the disconnection. For Shifris, hospitalization was just another link in the chain of the plot to steal Yemenite babies.

According to Shifris, after a long period in the hospitals, if the babies were not claimed, they were shipped to American Zionist institutions operating in Israel, such as the WIZO and Hadassah, and from there were adopted. “The end testifies to the beginning . . . this was the purpose of this whole route,” he concludes. And yet, in this massive book of more than eight hundred pages, Shifris does not provide evidence of a single Yemenite who was kidnapped, although today simple DNA tests can trace members of biological families, and if thousands of babies were stolen, one would expect at least some cases to surface.

So far, there have been three published rebuttals to Shifris’s theory, each of them persuasive, though none has so far put the apparently baseless allegations to rest. Yechiel Bar-Ilan, from Tel Aviv University’s School of Medicine, notes that Shifris dismisses not only the medical records of the time but the evidence of serious diseases among the Yemenite immigrant population. Once one takes this into account, it was entirely reasonable to remove babies with seemingly commonplace symptoms like fever, diarrhea, stomachaches, and eye infections from the tent camps and take them to the sterile conditions of the Batei Tinokot or the hospitals. The judgments were medically sound, even if they were not explained to the parents or humanely implemented.

Avshalom Ben-Zvi and Avi Picard have attacked Shifris’s historical methods, which, despite his training, consist of relying only on verbal testimony given long after the events in question, while disregarding contemporary documents. Shifris simply refuses to acknowledge that memory is slippery, and yet, Ben-Zvi and Picard demonstrate how the testimonies of the very same people changed over the years as they testified before two or three different commissions.

Finally, writing in Tablet, Yaakov Lozowick, head of Israel’s State Archives, noted that in addition to there being “no documents that tell or even hint at a governmental policy of kidnapping children,” the charge is almost self-refuting:

Had there been such a practice, there would by necessity be hundreds or thousands of elderly dark-skinned Israelis who grew up in light-skinned families in the 1950s and ’60s. These people don’t exist. So, the activists claim, the babies were exported and sold to rich and childless Jewish families in America, or perhaps elsewhere. The archives contain not a shred of evidence for this claim, either.

Lozowick speculates that the reason authorities decided to bury the babies without their parents’ knowledge or consent is that autopsies had been conducted on the bodies. The body of an infant after an autopsy has been performed is not something one wishes to show grieving parents, certainly not religious parents from an undeveloped country who did not speak modern Hebrew or understand medical science—and, it must be noted, never gave their permission for their children to be hospitalized, let alone for their corpses to be autopsied.

Tova Gamliel, the coeditor of Children of the Heart, like many other scholar-activists nonetheless believes in the kidnapping narrative and called upon the State of Israel to offer justice, acknowledgment, and healing. In February 2021, the State of Israel decided to compensate all the families who had testified before the different inquiry committees. The compensation decision, which was made only a few days before the 2021 elections, in what was at least in part an attempt to sway votes, did not admit that the state had kidnapped Yemenite children. Rather, the payments were made to compensate for the pain that the families endured when their babies died and were buried without them, a truly terrible thing. Activists urged the families not to accept the payments, which amounted to about $45,000, while also claiming that the offer validated the kidnapping narrative.

Scholar-activists, including many in the volume edited by Shifris and Gamliel, and others want to make the kidnapping narrative a test case for the soul of the State of Israel. The Yemenite Children Affair has become another way to attack Israel’s founders and portray the state as a criminal enterprise. It is a tempting story of original sin that taps into current ideas about race, class, and neocolonialism, but it has no historical basis. With all the data that is available today, it has instead become a test case for the soul of the academics, journalists, and activists who dismiss a mountain of evidence in favor of conspiracy theories.

Suggested Reading

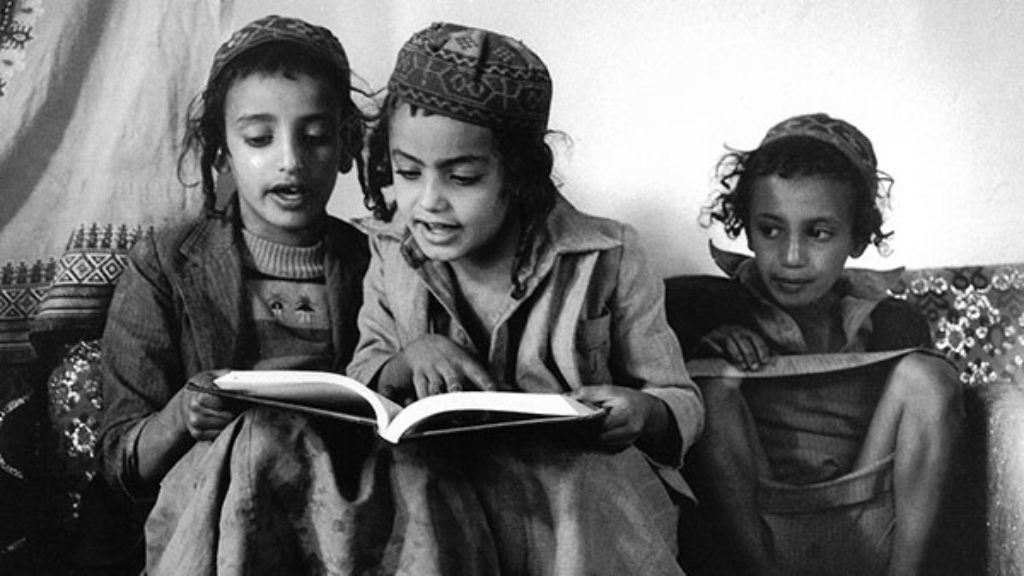

Available Light: Pictures from Yemen

Yihye Haybi, a Jewish medical assistant to an Italian doctor in Sana'a, found himself in possession of a camera. Self-taught and working under difficult circumstances, he captured the waning days of Yemen's ancient Jewish community.

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

The War on History

"People have often asked me if something like the revisionist Israeli historiography to which I contributed in the late 1980s exists on the Palestinian side."

Ireland and the Promised Land

Why isn’t Israel more like America, Jews from that country wonder. In his ambitious new book, Alexander Kaye instructively raises the question of why Israel isn’t even less like the United States.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In