What . . . Him Worry?

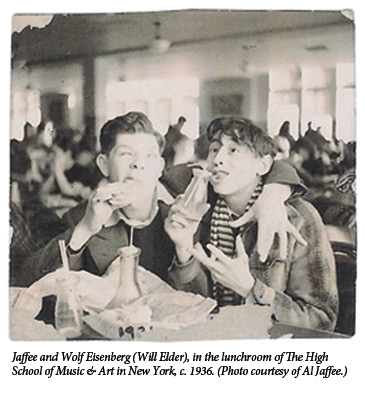

In 1936, Abraham Jaffee, a rambunctious, clever student at Herman Ridder Junior High School in the Bronx, was told to report to the art room. When he and fifty other children were told to draw something, he began a detailed rendering of the village square in Zarasai, Lithuania, where he had lived from ages 6 to 12. Wolf William Eisenberg, the skinny, freckle-faced boy sitting in front of Abraham, drew a portrait of a peasant. When the assignment was over, Abraham and Wolf were both sent to the principal’s office. Abraham was frightened until Wolf—who would later be known as the cartoonist Will Elder—leaned over and, in his thick Bronx accent, intoned, “I tink dere gunna send us to art school.”

In Al Jaffee’s Mad Life, Mary-Lou Weisman tells the story of how this young Abraham, raised in the shtetl of Zarasai, became one of MAD magazine’s most prolific and recognizable cartoonists. The recurring features that Al Jaffee has created for MAD, such as “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” and especially the ingenious back-page “MAD Fold-In,” are as closely associated with MAD as are “Spy Vs. Spy” or the magazine’s “What . . . Me Worry?” mascot, Alfred E. Neuman. (Elder would also become one of MAD‘s star cartoonists, during its formative years in the 1950s.) Weisman received Jaffee’s full cooperation and the book features several dozen autobiographical illustrations by Jaffee himself, still active at age 89.

In Al Jaffee’s Mad Life, Mary-Lou Weisman tells the story of how this young Abraham, raised in the shtetl of Zarasai, became one of MAD magazine’s most prolific and recognizable cartoonists. The recurring features that Al Jaffee has created for MAD, such as “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” and especially the ingenious back-page “MAD Fold-In,” are as closely associated with MAD as are “Spy Vs. Spy” or the magazine’s “What . . . Me Worry?” mascot, Alfred E. Neuman. (Elder would also become one of MAD‘s star cartoonists, during its formative years in the 1950s.) Weisman received Jaffee’s full cooperation and the book features several dozen autobiographical illustrations by Jaffee himself, still active at age 89.

It isn’t hard to see why a gifted boy like Abraham Jaffee would be obsessed with the notion of cobbling together something out of nothing. Born in Savannah, Georgia, Jaffee experienced a taste of the modernity and luxury of America, before being thrust into a comparatively rustic corner of Lithuania. Weisman conveys the panic that Jaffee felt when his mother Mildred, or Michlia, took him and his three brothers back to Zarasai, leaving his father Morris behind. Mildred, already a psychologically fragile woman, was horrified that her husband was obliged to work on the Sabbath in his job at Blumenthal’s department store, by the difficulty of keeping kosher, and by America more generally. Morris, on the other hand, was, as Jaffee recalls “a dandy” who “felt like a million bucks” in America, “and was very, very eager to join the twentieth century.”

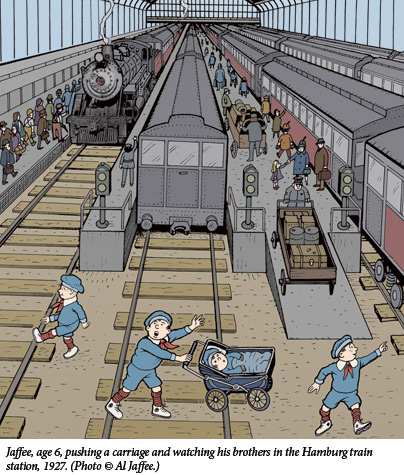

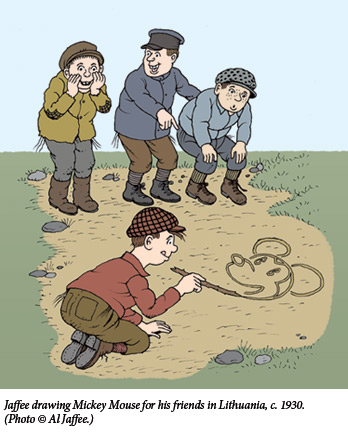

During his childhood years in Zarasai, Jaffee’s father kept in touch with his children by mailing cardboard tubes stuffed with newspaper comic strips, which Jaffee would read to his brothers and try to copy. However, as time wore on and Morris’ work situation became dire, these comic-strip care packages became less and less frequent. Adding to Jaffee’s misery was the fact that his mother was rarely around, and as the first-born child in the family, it often fell on him to take care of his three siblings. On the way to Lithuania, in the Hamburg train station, he had had an epiphany while trying to take care of his younger brothers after his mother had wandered off: “I realized that she was irresponsible. That I knew better than she did. I knew I could not put my life in her hands. I knew I was on my own.” When Jaffee finally returned to America, his mother stayed behind, and was almost certainly murdered when the Nazis liquidated the town a few years later.

|

|

Curiously, in late-life, Jaffee, who calls himself a “lapsed Jew,” has contributed several cartoons to the Lubavitcher children’s magazine The Moshiach Times. He does it, he says, because he retains a fondness for “the kind and gentle souls of the people of Orthodoxy . . . or maybe I’m doing penance for my mother.”

What effect did all this have on Jaffee’s eventual career? Jaffee is best known for the artistic ingenuity displayed in his famous “fold-ins,” in which the back-page illustration is transformed into a second image that wittily comments upon the first when the page is folded into thirds. Several generations of MAD readers remember their astonishment at the transformation when one simply folded the tabs “so ‘A’ meets ‘B.'” Weisman traces the origins of Jaffee’s comic inventiveness (“The Automated Ferris Wheel Rapid Parking Facility!”) to his difficult childhood years in Lithuania, where he and his brother were forced to invent their own toys. As Weisman notes, “This childhood pleasure of making things from virtually nothing would turn Al into a lifelong scavenger and inventor who prefers homemade to store-bought.”

There is also, of course, the familiar biographical irony of a miserable childhood leading to a career in comedy. Weisman sees Jaffee’s “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions,” in which put-upon wiseacres respond to inane queries, as “Al’s way of getting back at everyone who had ever put him down, beaten him, starved him, neglected him, [or] abandoned him.” This is probably true, though it is questionable whether it gets to the manic source of Jaffee and MAD‘s perpetual adolescent brio.

It is precisely here that Al Jaffee’s Mad Life falls a little short. The bulk of the book concentrates on Jaffee’s early years. Once Weisman reaches the point where Jaffee becomes a success at MAD—and goes on to draw cartoons for Harvey Kurtzman, Hugh Hefner, and others—the book is almost over.

The reader comes to understand the personal demons that drove Jaffee’s “mad life” (when he grew up, Jaffee himself became a self-admittedly indifferent parent), but not quite how they led to the antics of MAD. Nonetheless, one does get a vivid picture of Abraham Jaffee, the kid who tinkered with intricate inventions because, like a well-made joke, they were the part of life one could control: fold the page over left and then back “so ‘A’ meets ‘B.'”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Adventure Story

The story of Hebrew is a great story because there is nothing inevitable about it. Whether it was the period of the Bible or the Mishnah or Maimonides, there was always a danger, often the likelihood, that Hebrew would be lost in the break-up of great communities and subsequent migrations.

Do You Want to Know a Secret?

“Who’s this guy,” asked one of my sister’s friends, “who writes about secret truths? I can’t remember his name.”

Our Exodus

How did a high-school dropout named Leon Uris pen one of the most influential novels of all time?

No Simple Return

“I stepped into the air.” Hilde Domin wrote, “and it carried me.”

Robert S. April MD MA

Another example of Holocaust art -- created by a witness. The mystical combination of innate talent and the realistic stresses of a childhood from Hell, transformed into an expressive form that connects with the inner feelings and needs of the reader-- why worry about the Devil's messengers when you can reconfigure them to the madcap figures that Al Jaffee created for all of us. And the Phoenix shall arise out of the ashes of the dead.

Keep going, Al, till 120.......at least.