Wonder and Indignation: Abraham’s Uneasy Faith

The book of Genesis never tells us why God fell in love with Abram. Jewish tradition has often tried to fill in the blanks, to tell us something about the patriarch that would explain God’s embrace of him and his descendants. Surely, at least some of the rabbinic sages seem to have thought, Abram must have done something to earn God’s affection? The most famous answer is that Abram fearlessly destroyed his father’s idols, exposing the theological bankruptcy of idolatry. So celebrated and widespread is this story that many Jews are shocked to learn that it is not found in the Bible itself.

But there is another, less well-known rabbinic story of covenantal beginnings that is worth reading closely. As it has often been translated, the midrash reads as follows:

The Lord said to Abram, “Go forth from your land” (Gen. 12:1) . . . R. Isaac said: To what may this be compared? To a man who was traveling from place to place when he saw a palace full of light (doleket). He wondered, “Is it possible that this palace has no one who looks after it?” The owner of the building looked out at him and said, “I am the owner of the palace.” Similarly, because Abraham our father wondered, “Is it possible that that this world has no one who looks after it?” the Blessed Holy One looked at him and said, “I am the owner of the world.”

According to this story, Abram intuits or infers a divine creator from the fact that the universe is “lit up.” One imagines Abram at this moment as thunderstruck by the sheer beauty of creation, perhaps even sensing a pervasive meaningfulness in the cosmos. In God in Search of Man, Abraham Joshua Heschel reads this story as suggesting that religion begins with “what man does with his ultimate wonder, with the moments of awe, with the sense of mystery.” Louis Jacobs interprets it as an early form of what philosophers would later call “the teleological argument” for the existence of God, or “the argument from design.” Heschel and Jacobs have precedent for their interpretations. A commentary attributed to the great medieval sage Rashi explains that Abram “saw heaven and earth—he saw the sun by day and the moon by night, and stars shining. He thought, ‘Is it possible that such a great thing could be without its having a guide?’ Whereupon God looked out at him and announced, ‘I am the owner of the world.'”

But beautiful as these interpretations undeniably are, they are beset by a major linguistic difficulty: in rabbinic Hebrew, mueret would have been the word to use to describe the world as “lit up” or “full of light,” whereas the word actually used in the midrash, doleket, means “in flames.” This seemingly small philological point yields a dramatic theological difference:

The Lord said to Abram, “Go forth from your land” (Gen. 12:1) . . . R. Isaac said: To what may this be compared? To a man who was traveling from place to place when he saw a palace in flames (doleket). He wondered, “Is it possible that this palace has no one who looks after it?” The owner of the building looked out at him and said, “I am the owner of the palace.”

It is one thing to behold order, beauty, or meaning and be led to an awareness of God. But to behold a “palace in flames” and thereby be led to God? What are we to make of this bold and disturbing story? Heschel, who knew his rabbinic Hebrew, considered this reading as well:

There are those who sense the ultimate questions in moments of wonder, in moments of joy; there are those who sense the ultimate question in moments of horror, in moments of despair. It is both the grandeur and the misery of living that makes man sensitive to the ultimate question . . . The world is in flames, consumed by evil. Is it possible that there is no one who cares?

So far from wonder, Abram here discovers God from the very midst of moral and existential anguish. Here, too, Heschel has precedent. Reading our story, the 18th-century scholar Rabbi David Luria explains that “when Abraham saw that the wicked were setting the world on fire, he began to doubt in his heart: perhaps there is no one who looks after this world. Immediately, God appeared to him and said, ‘I am the owner of the world.'”

Abram’s question does not arise from contemplation or wonder. It is more like an exclamation of horror: “Is this really what the world is like?!” As soon as he asks that question, God appears to him and says—perhaps reassuringly, perhaps just matter-of-factly-“I am the owner of the world.”

But why? What happens here, exactly-for Abram, for God, and between Abram and God? This text does not tell us most Bof what we want to know. And yet perhaps that is part of its richness—it asks us to do the work of imagining Abram in his moment of consternation and bewilderment, and to speculate about how that very state led him to God. It forces us to question, too, what it is about Abram’s state of agitation that elicits God’s self-revelation.

Perhaps the first basis of Abram’s greatness is precisely his refusal to look away. But there is more. Not only does Abram refuse to turn away, he cares: “Is it possible that this world has no one who looks after it?!” Whatever faith this Abram finds, it will not be easy: it will be the faith of a man who has considered the very real possibility that chaos and bloodshed are simply all there is.

According to this tradition, the founding father of the Jewish people is a man who will not avert his eyes from the reality of human suffering. But something else may be going on here as well. It may be counter-intuitive to some, but I imagine something extremely powerful bubbling just under the surface of Abram’s outrage. In the fervor of his question, an answer is already implicit—or maybe not an answer, precisely, but at least an intimation of profound faith.

If Abram’s question is, at heart, really a protest, then that very protest itself can be said to reveal—again, quite possibly unconsciously—a deep and abiding sense that things are meant to be otherwise. The insistence that the word is not yet the world as it must be, as it is in some ultimate way intended to be, is itself a manifestation of faith. When God peers at Abram and announces that “I am the owner of the world,” then God is only making explicit what is already implicit in Abram’s anguished cry.

In a similar vein, the Christian theologian Miroslav Volf writes of his urge to protest in the face of natural disasters:

Why are we disturbed about the brute and blind force of tsunamis that snuff out people’s lives? . . . If the world is all there is, and the world with moving tectonic plates is a world in which we happen to live, what’s there to complain about? We can mourn—we’ve lost something terribly dear. But we can’t really complain, and we certainly can’t legitimately protest. The expectation that the world should be a hospitable place . . . is tied to the belief that the world ought to be constituted in a certain way. And that belief—as distinct from the belief that the world just is what it is—is itself tied to the notion of a creator.

What Volf says about natural disasters can be extended to humanly inflicted devastation as well. The overwhelming certainty that this—a world of crushing poverty, degrading oppression, and murderous hatred—is not how things are meant to be testifies to the possibility of something different, and perhaps also to the Source of Life, who, Jewish theology insists, wants something different and summons us to help build it.

Our midrash is so terse as to elude any definitive interpretation, and even more radical readings are possible. In a brilliant article, Paul Mandel has suggested that the God who responds that he is the owner of the building is, in fact, trapped in the fire. But it does seem clear that the passage is not attempting to express an argument for God’s existence. Instead, it evokes a primal religious experience. Volf articulates this well: “God is both the ground of the protest and its target . . . I protest, and therefore I believe.”

What does God expect from Abram? Not surprisingly, given what Abram has intuited about God and the world, he and his descendants are called to embody a different way of being in the world, to present a living alternative to the horrors of the world as it is: “For I have singled him out,” God says, “that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is just and right” (Gen. 18:19).

Jonathan Sacks takes this midrashic story and the moral protest that underlies it as the very starting point of Jewish faith. Judaism, he insists, “begins not in wonder that the world is, but in protest that that the world is not as it ought to be. It is in that cry, that sacred discontent, that Abraham’s journey begins.”

Yes, I think, and no. Even if it does not motivate this midrash, wonder at the beauty of the universe and gratitude to its creator is the other pole of Jewish faith. Zev Wolf Einhorn, a 19th-century commentator, expresses this well. Abram, he writes, is like a person who sees a beautiful building and realizes that it must have had both a wise architect and a devoted owner. But since it is being left to burn he imagines it to have been abandoned. Here, Abram senses order and confronts chaos at the very same time. Like many of us, he discerns powerful reasons to believe and powerful reasons not to. And it is precisely this honesty that leads God to embrace him as a covenantal partner.

“The faith of Abraham,” Sacks writes, “begins in the refusal to accept either answer, for both contain a truth, and between them there is a contradiction . . . The first says that if evil exists, God does not exist. The second says that if God exists, evil does not exist. But supposing both exist? Supposing there are both the palace and the flames?” There is a magnificent palace, and yet it is in flames. Abram, the paradigmatic Jew, is simultaneously grateful and indignant.

To have a sense of wonder, Heschel argues, is to know that “something is asked of us.” The Catholic essayist G.K. Chesterton made this point eloquently:

What we need is not the cold acceptance of the world as a compromise, but some way in which we can heartily hate and heartily love it. We do not want joy and anger to neutralize each other . . . We have to feel the universe at once to be an ogre’s castle, to be stormed, and yet as our own cottage, to which we can return at evening.

It is Abram’s achievement to have stormed the castle and made it home. In responding to the world in both wonder and indignation, he became Abraham—party to the covenant, father of a nation, and paragon of mature faith.

Suggested Reading

Reader Review Competition

Review a book for us and perhaps win a book in return!

All-American, Post-Everything

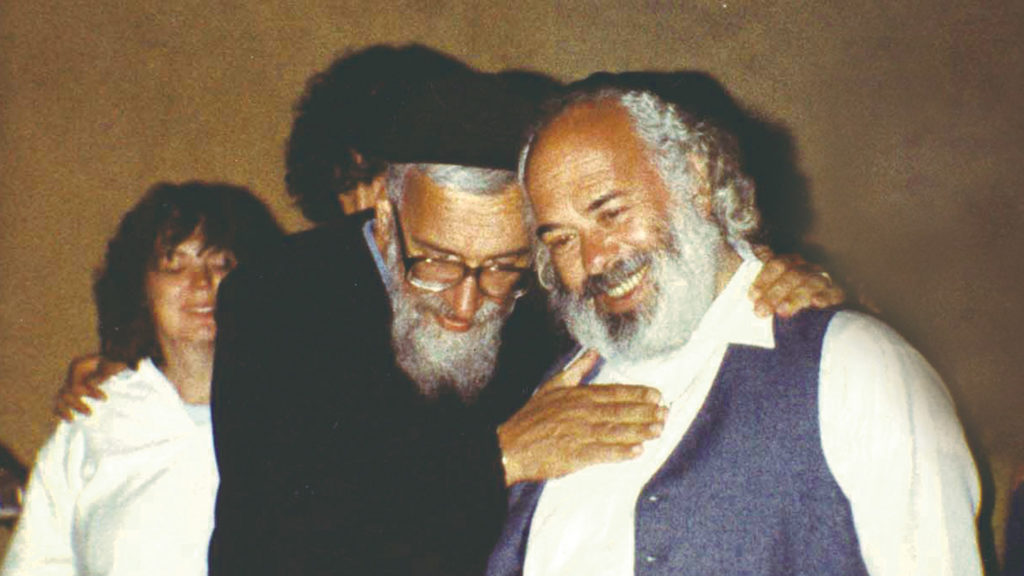

Shaul Magid argues that Zalman Schachter-Shalomi is the Rebbe for post-ethnic America. But is cosmotheism a good idea?

The Sephardic Mystique

In the late 18th century, an ardor for ancient Greek art and literature swept through German letters. German Jews were not immune, yet during the same period, they also devoted themselves to recovering the linguistic, artistic, and literary heritage of medieval Sephardic Jewry.

The Future Past Perfect

Treasure and tragedy in the letters of Stefan and Lotte Zweig, one of the most famous literary couples of the early 20th century.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In