Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

Like many of their readers, American Jewish magazines changed their names: The periodical known as Jewish Currents, for example, first came into the world in the 1940s as Jewish Life. Styling itself a “progressive” magazine, often a byword in postwar America for an avowedly communist enterprise, it shared its innocuous-seeming title for a spell with the house publication of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, confounding subsequent generations of historians.

Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Jewish Life published detailed and impassioned articles about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, whose fighting spirit inspired its own, and the “Negro question” in the United States, often linking the two. In an ongoing effort to deepen its readers’ understanding of the dire conditions of African American life and to inspire them to make common cause with the African American community, the magazine’s editors repeatedly invited Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois to contribute to its pages.

“We are anxious to include an article on the relationship between the struggle against anti-Semitism and all forms of anti-Negroism,” Samuel Barron, the magazine’s managing editor, wrote to the prominent African American leader and elder statesman in November 1947, hoping he would accept the assignment. Du Bois declined, citing too many demands on his time.

Two years later, Louis Harap, Barron’s successor as managing editor, tried again to persuade Du Bois to write for the magazine. “You are no doubt acquainted with Jewish Life and the work it is doing on the oppression of Negroes and national groups in the United States in addition to the Jewish question. However, we feel that we have not yet done enough, either on the Negro problem or on Negro-Jewish relations. I know you are probably deluged with requests of this kind,” Harap continued, “but I hope very much that you will respond favorably to this one in view of the need for closer liaison between the Negro and Jewish movements.” Once again, Du Bois declined.

Two years later, Louis Harap, Barron’s successor as managing editor, tried again to persuade Du Bois to write for the magazine. “You are no doubt acquainted with Jewish Life and the work it is doing on the oppression of Negroes and national groups in the United States in addition to the Jewish question. However, we feel that we have not yet done enough, either on the Negro problem or on Negro-Jewish relations. I know you are probably deluged with requests of this kind,” Harap continued, “but I hope very much that you will respond favorably to this one in view of the need for closer liaison between the Negro and Jewish movements.” Once again, Du Bois declined.

Jewish Life persisted. Having learned of a trip Du Bois had taken to Warsaw in the aftermath of World War II, the magazine’s editorial board thought he might offer a deeply informed and personal perspective on the contemporary relevance of the Warsaw Ghetto. In February 1952, it invited the African American civil rights crusader to participate in a “Tribute to the Warsaw Ghetto fighters,” which was scheduled for April 16, on the ninth anniversary of the uprising, at Manhattan’s Hotel Diplomat on West 43rd Street. “We should be honored if you would consent to speak – perhaps for fifteen minutes – on the significance of the ghetto fight for the Negro people in the United States today in relation to cooperation with their allies, the Jewish people and the common people of America,” read the invitation, somewhat lumberingly.

Jewish Life was right to think that Du Bois would have what to say. In a letter to his friend and patron, Anita McCormick Blaine, penned shortly after returning to the States, he gave voice to both despair and hope at what he had encountered in postwar Poland. “I never thought it possible that human beings could do to each other in modern days what the Germans did to Warsaw,” Du Bois wrote in September 1949, adding, “In some cases, there was nothing but dust left.” He was equally taken with its residents’ commitment to renewal, observing that the “city is rising again and anew and the spirit of the people is extraordinary.”

This time around, in 1952, the right occasion and the right subject neatly came together, prompting Du Bois to accept the magazine’s invitation. “He asks me to say that if he can speak plainly with his new teeth, he will talk 15 minutes for your organization on April 16,” responded Lillian Hyman, his secretary, on behalf of her boss.

And so he did, taking his place on the stage of the Hotel Diplomat’s ballroom alongside the Edith Segal Mitlschul Dance Group and the Jewish Young Folk Singers, a brand new, interracial chorus whose “youthful verve” and “delightful joyousness of spirit” enlivened the proceedings. Du Bois’s remarks, which were subsequently published in the May 1952 issue of Jewish Life under the title “The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto,” deepened them.

At once a personal account and a history lesson, his presentation built on the impressions he had committed to paper several years earlier, enlarging their circumference.

I have seen something of human upheaval in this world: the scream and shots of a race riot in Atlanta; the marching of the Ku Klux Klan; the threat of courts and police; the neglect and destruction of human habitation; but nothing in my wildest imagination was equal to what I saw in Warsaw in 1949. I would have said before seeing it that it was impossible for a civilized nation with deep religious convictions and outstanding religious institutions; with literature and art; to treat fellow human beings as Warsaw had been treated. There had been complete, planned and utter destruction.

“[O]ne afternoon,” Du Bois told his audience, “I was taken out to the former ghetto. I knew all too little of its story although I had visited ghettos in parts of Europe, particularly in Frankfurt, Germany. Here there was not much to see. There was complete and total waste and a monument. And the monument brought back again the problem of race and religion, which so long had been my own particular and separate problem.” (Du Bois had in mind Nathan Rapoport’s then recently dedicated sculptural salute to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, which, in James Young’s words, stood amidst and drew its power from the adjacent “landscape of debris,” its “moonscape of rubble, piled sixteen feet high.”)

“Gradually, from looking and reading,” Du Bois continued, “I rebuilt the story of this extraordinary resistance to oppression and wrong . . . a resistance which involved death and destruction for hundreds and hundreds of human beings; a deliberate sacrifice in life for a great ideal in the face of the fact that the sacrifice might be completely in vain.”

The result of his visits, he ringingly concluded, “was not so much clearer understanding of the Jewish problem in the world as it was a real and more complete understanding of the Negro problem . . . the ghetto of Warsaw helped me to emerge from a certain social provincialism into a broader conception of what the fight against race segregation, religious discrimination and the oppression by wealth had to become if civilization was going to triumph and broaden in the world.”

In the years that followed, the editors of Jewish Life continued to keep in touch with Dr. Du Bois, inviting him to participate in a 1953 “mass rally” and 10th anniversary commemoration of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in New York, proposing he write for the magazine on “Negro-Jewish relations” and on school segregation, and sending him a telegram on his 85th birthday: “We do you most honor by continued common struggle with Negro people and all progressives and equality.”

In every instance, Jewish Life initiated these exchanges. But in 1954, Du Bois himself began a conversation by turning to Harap for guidance. He tells him about a character in a novel that he is writing—a German rabbi who survived the “Hitler massacre”—who, by chance, encounters an African American college president whom he had met years before. The survivor would like to pronounce a Hebrew blessing on his long-lost friend. “What would he say?” asks Du Bois of his dyed-in-the-wool-left-wing-secularist colleague at the helm of Jewish Life. “Please give me a quotation.”

Harap was eager to oblige but didn’t know how, so he turned to Joshua Bloch, the distinguished bibliographer, longtime head of the New York Public Library’s Jewish Division, and an ordained rabbi, for a liturgical assist. On Christmas Eve 1954, in a letter preserved in the W. E. B. Du Bois collection at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Harap furnished Du Bois with the text of the traditional priestly benediction—in both English and in Hebrew transliteration.

Du Bois would go on to make use of the blessing in the concluding pages of Worlds of Color, the last volume of his Black Flame trilogy. At once a sweeping work of historical fiction and a rueful self-portrait, it follows the life and times of Manual Mansart, the president of a historically black college in Georgia.

In the 1961 novel’s last dramatic set piece, an aging Mansart is unceremoniously expelled from a conference of “Negro leadership in Africa and America” for his radicalism. “Black Brothers, let us never sell our high heritage for a mess of such White Folks’ pottage!,” he tells the assembly, among them a Jewish clergyman named Rabbi Blumenschweig, who turns out to be the character Du Bois had first mentioned to Harap. In the novel, the rabbi met Mansart in Nazi Berlin in 1936 and, years later, encouraged him to attend this international gathering. The two men exit together. Just as the ailing Mansart is about to get into a cab, the clergyman, “his head uncovered and his white hair blowing in the frosty night,” places his hands on his old friend’s shoulders and blesses him:

Yevorechecho Adonoi veyishmerecho;

Yoer Adonoi ponov eilecho vichuneko;

Yiso Adonoi ponov eilecho veyosem lecho sholom.

Mansart dies several pages later, his legacy—and that of his creator—hallowed by an age-old Jewish prayer.

Permission to publish correspondence was granted by Jewish Currents, The David Graham Du Bois Trust, and the W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Suggested Reading

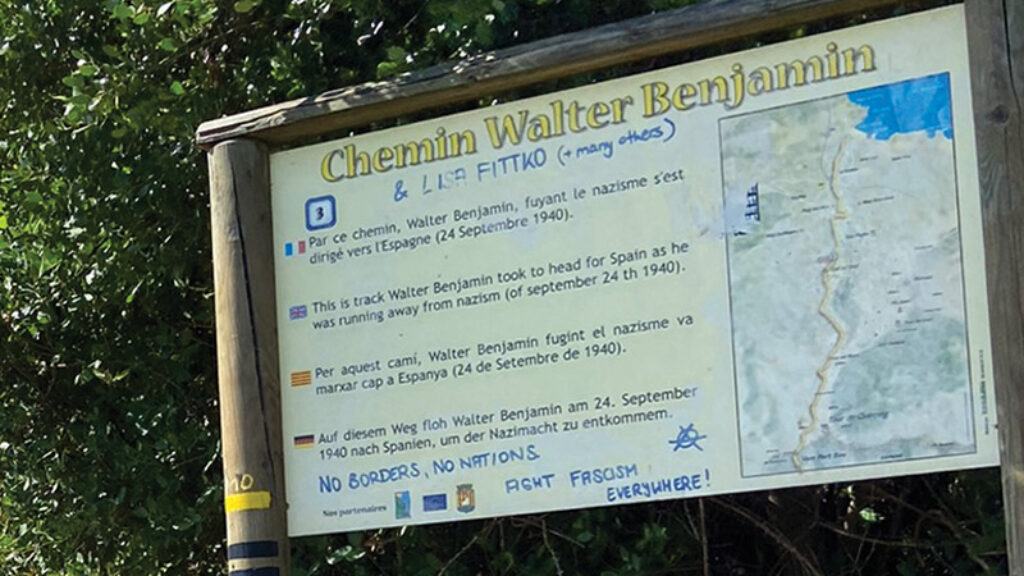

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

Eco’s Elders of Zion

Umberto Eco's new novel highlights—or exemplifies—the real history of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, intertwined as it is with bad fiction.

Wink-Wink, Win-Win?

The question of conversion has plagued Israeli public discourse since at least 1957, when the National Religious Party protested that roughly 10 percent of immigrants from Russia and Poland were not Jewish under strict halakhic standards.

Zion and Party Politics, 1944

In the summer of 1944 support for Zionism was transformed from a low-risk political gesture to a bona fide election issue. FDR was not pleased.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In