Torah U’Madda

Only 3 percent of American Jews are Modern Orthodox, but it’s still an umbrella term. As Zev Eleff notes in the preface to his fascinating documentary history, Modern Orthodox Judaism, those now looking for matches on Modern Orthodox dating sites have the option of identifying as “‘modern Orthodox-liberal’ or ‘modern Orthodox-machmir’ (stringent).” I know from first-hand experience that these distinctions are real, even though I still have difficulty figuring out where the lines are drawn and where I belong. Some daters even identify themselves as “modern yeshivish” (a sort of hybrid between Modern Orthodox and yeshivish), others as “Carlebachian” (anyone’s guess, but musical), and others as simply “shomer mitzvot” (observant).

Turning from dating sites to sociologists (and ideologues), the crucial dividing line seems to be between the “centrist Orthodox” and the “Open Orthodox” camps, though religious lives and affiliations are often more complicated than such bright-line drawing suggests. Nonetheless, there is much variation in belief and practice (especially around women’s roles in the synagogue and communal life) within Modern Orthodoxy.

Have things always been this way? Eleff’s thick anthology is an excellent place to look for the answer. His book tells the story of Modern Orthodoxy in America—from the early 19th century up until the present—through a series of significant speeches, essays, article excerpts, and responsa from many of the key figures and shapers of the movement. He takes us on an all-encompassing, whirlwind tour of Orthodoxy in America, from its embryonic stages—it first emerged in 1825 in Charleston, according to Eleff, as a reaction to the local Jews who broke away from traditional Judaism to found the Reformed Society of Israelites—to its early struggles to differentiate and dissociate itself from Conservative Judaism, to its maturation as a movement, to the present day.

The history of self-consciously “modern” Orthodoxy is inseparable from the history of Yeshiva University, which is a product of the early 20th century. Eleff covers Yeshiva University’s birth, development, and evolution, and provides a chronicle of reactions to it from both its conservative and liberal Orthodox critics. As an alumnus of both Yeshiva University and Yeshiva University High School for Boys, I emerged from this book with a much greater appreciation for Bernard Revel, the founder of both institutions. Without his vision of a unique educational institution that manifested a “harmonious union of culture and spirituality” and trained “the Jewish heart and will as well as the mind,” my learning and my life as well as the lives of tens of thousands of other Orthodox Jews who have aspired to live up to Yeshiva University’s motto of Torah U’Madda (Torah and [secular] knowledge)—would not have been possible.

Of course, the definitions of both Torah and madda have been contested. In April 1966, Yeshiva College’s student newspaper interviewed the school’s popular professor of Jewish history Rabbi Dr. Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, who thought that Orthodoxy was losing ground because it was dodging “the challenge of contemporary civilization.” Orthodoxy, he argued, had to update itself by coming to terms with, among other things, modern biblical scholarship and by developing “a new value system and corresponding new halachot about sex.” In response, another young faculty member, Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein, published an open letter to Greenberg, in which he admonished Greenberg to “ponder the wisdom of Fulton Sheen’s remarks that ‘he who marries his own age will find himself a widower in the next.’” Greenberg would, of course, become a leader of the left wing of Modern Orthodoxy, while Lichtenstein would go on to become the rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Etzion, Israel’s leading centrist Modern Orthodox yeshiva.

The debate that began with the Greenberg–Lichtenstein exchange has now been raging for more than half a century. It continues throughout this volume, from Rabbi Shlomo Riskin’s “Modern Orthodoxy Goes to Grossinger’s” (1976), in which he asks whether “it is any wonder that with all of our yeshivos, American Orthodoxy has produced so few genuine Talmidei Chachemim,” to David Singer’s “A Modern Orthodox Utopia Turned to Ashes” (1982), in which he laments that “our children—my children—will grow up in an Orthodox world in which talk about ‘synthesis’ will seem totally alien.” The anthology’s last chapter brings things up to the present, with Dov Linzer and Avi Weiss’s “Open Orthodox Judaism” (2003), which makes the case for “an Orthodoxy that is open intellectually and expansive and inclusive in practice,” and Asher Lopatin’s “Taking Back Modern Orthodox Judaism” (2014), which calls for retrieving a better “appreciation for what an engagement with modernity could do to make us better Jews and scholars of Torah.” Eleff briefly touches upon the opposition that Open Orthodoxy and its rabbinical school Yeshivat Chovevei Torah have encountered on the right but does not include any documents rebutting Open Orthodoxy (of which the Modern Orthodox world has not been lacking in the past two decades). One thinks, for instance, of Avrohom Gordimer of the Orthodox Union, who has been pillorying Open Orthodoxy since 2013 in the Cross-Currents blog, describing it as “the rebirth of Conservative Judaism.”

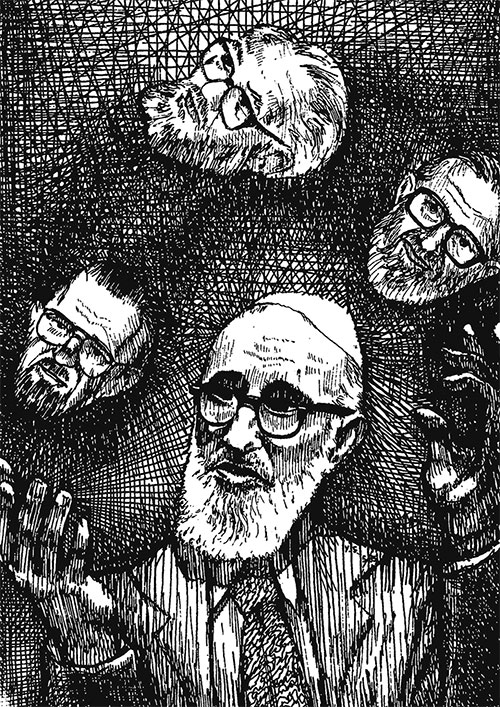

Of course, the book also contains several key statements from Modern Orthodoxy’s most outstanding spokesmen: the great halakhist and thinker Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Rabbi Norman Lamm, who served as the president of Yeshiva University from 1976 to 2003. A distinguished congregational rabbi, Lamm, unlike Soloveitchik, clearly, albeit hesitantly, identified himself as Modern Orthodox, as a 1969 essay in this volume demonstrates. His 1990 book, Torah Umadda, articulated his vision of a Maimonidean Judaism that is fully committed to the observance of Jewish law while being open to science, the humanities, and secular culture more generally. According to Lamm, such a synthesis could together accomplish what neither Torah nor madda could achieve separately.

Although Rabbi Lamm has been a central figure of inestimable importance in Modern Orthodoxy for nearly seven decades, graduates of Yeshiva University, and anyone even tangentially connected to the institution, are well aware of the fact that it has not been Rabbi Lamm but rather Yeshiva University’s roshei yeshiva—authoritative halakhists and brilliant talmudists such as Hershel Schachter, Mordechai Willig, Meir Goldwicht, Mayer Twersky, and Zvi Sobolofsky—who have, arguably, had a more direct impact upon the lives of thousands upon thousands of American Modern Orthodox Jews. It is surprising, then, that a volume that features so many texts related to Yeshiva University all but completely excludes the figures who can be said to have been the university’s most influential rabbis.

Despite Rabbi Lamm’s eloquent and intellectually sophisticated elucidations of the Modern Orthodox world view, Modern Orthodoxy has failed to attract as many adherents as ultra-Orthodoxy—the American ultra-Orthodox population is currently twice as large as (and growing faster than) the Modern Orthodox population—a challenge to the movement that Eleff does not ignore. The ideology of Modern Orthodoxy, undergirded by Rabbi Soloveitchik’s distinctive blend of existentialism and neo-Kantianism, is a difficult one to grasp. Most people prefer clear lines and black-and-white differentiations to living with complexity, and it doesn’t help matters that even many of those rabbinic leaders who understand Soloveitchik’s philosophy and embody its values, such as Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, do not identify themselves as Modern Orthodox. This, combined with growing pressure from its right and left flanks, the prohibitive cost of the Modern Orthodox life (the “tuition crisis” is consistently cited as the greatest problem of religious life by Modern Orthodox Jews), widespread theological uncertainty (the 2017 Nishma survey found that only 64 percent of Modern Orthodox Jews believe that the Torah was given at Sinai), and a continuous “brain drain” in which many of the most committed American Modern Orthodox Jews leave for Israel—Modern Orthodox Jews have the highest rates of aliyah among all American Jews—means that the movement’s future will likely be as ambiguous and complicated as its complex, tension-filled philosophy.

According to demographic projections, within two generations the majority of American Jews will be Orthodox, for the first time in nearly 150 years. How large a part of that community will be “modern”? And in what sense? In charting Modern Orthodoxy’s past and present, Eleff has given us tools that may help us foresee its future.

Suggested Reading

“The One You Love”? A Case of Divine Disappointment

Which son did Abraham favor? Reading "the binding of Isaac" with fresh eyes.

What’s Love Got to Do with It?

Shai Held measures up the sprawling mass of Jewish tradition and claims, against incredulous critics going back to Saint Paul, that love has a great deal to do with it.

The Good, The Bad, and The Unending

Have (more or less) real historians ever been as central to a Hollywood blockbuster as they are to George Clooney’s The Monuments Men? Our reviewer, Gavriel D. Rosenfeld has something to say about the history. Also Cate Blanchett.

Halakha and State: An Exchange

In our Winter 2016 issue, Elli Fischer explained why he defies the Israeli Chief Rabbinate and argued for radical reform. Four responses and his rejoinder.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In