Black Fire on White Fire

What is a Torah, exactly? If you were trying to explain it to a visitor from Mars, the easiest way might be to lead him to a synagogue, open the ark, and point: This scroll of parchment covered with ink is what Jews call a Torah. But of course such a response would not come close to exhausting the meaning of Torah for Judaism. After all, the ancient rabbis believed that it preexisted the created world, which obviously cannot be true of any physical object. Unlike every other book, which comes into existence only in the act of writing, the text of the Torah is prior to its script. When the Talmud says that the Torah given to Moses was written “in black fire on white fire,” it again emphasizes the distinction between the language of the Torah, which exists eternally (or, as we now say, virtually), and its physical medium.

It is a kind of paradox then that the Torah scroll is the most changeless of Jewish objects. If the original Torah was made of fire, why should it matter whether we read it as a parchment scroll or a printed codex, or for that matter on an iPhone screen? Why do Jews reading Torah in a synagogue today use exactly the same technology as their ancestors two thousand years ago? In the first chapter of The Jewish Bible: A Material History, his brilliant and fascinating new book, David Stern makes the point with a pair of images. One illustration depicts the oldest surviving complete Torah scroll, a product of Babylonia in the 12th century; the other shows a Torah scroll written in the United States in the 20th century (actually, a Torah in use at Harvard Hillel). Both are open to the same passage, the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15, which is written in a distinctive pattern known as “a small brick atop a full brick.” The text and its layout are identical in both scrolls; the passage of eight hundred years has changed the physical appearance of the Torah not at all.

As Stern points out, the highly conservative nature of the Torah scroll makes it difficult to study its history as an object. “Because these scrolls cannot contain any extratextual notes or features, it is very difficult to date or localize Torah scrolls with certainty or to trace their histories,” he writes. Yet in the last half-century, the scholarly turn toward “the history of the book”—to study books as the material objects that actual readers encountered rather than disembodied texts—has affected Jewish studies no less than other fields in the humanities. In The Jewish Bible, Stern masterfully synthesizes this scholarship, offering a chronological history of Jewish sacred books from Qumran to the JPS Tanakh. For if the Sefer Torah itself hasn’t changed, other ways Jews encounter their scripture definitely have. Indeed, as Stern shows, the Jewish book serves as a lens through which we can study central themes of Jewish history and thought.

The book itself—that is, the codex, whose pages are folded in half and bound with a cover—came relatively late to Judaism. Rabbinic tradition fixed the form of the Sefer Torah as a scroll; in tractate Bava Batra, the rabbis specify that the scroll’s height should ideally be equal to its circumference (though they acknowledge that in practice an exact ratio is very difficult to achieve). Thus, the scroll, which was originally a secular technology, became closely associated with Judaism at a time when Christians were adopting the codex for their holy books. Indeed, Stern writes, “Early Christians . . . may initially have seized upon the codex precisely to distinguish their scriptural texts from the rabbis’ Sefer Torah.”

Before long, Torah scrolls became cult objects—even, Stern argues, embodiments of the divine. To this day, they are decorated with crowns and kissed by worshippers. In the Middle Ages, folk tradition attributed magical powers to the Torah scroll: German Jews would bring one into a room where a woman was giving birth, while North African Jews would leave the ark open after prayers ended so that women “could approach it and address the Torah scrolls with special petitions and prayers for healing, fertility, livelihood, matchmaking, and the like.” Perhaps it is no coincidence that these traditions involved Jewish women, who were excluded from the reading of the Torah. If they could not use it as a text, at least they could interact with it as an object.

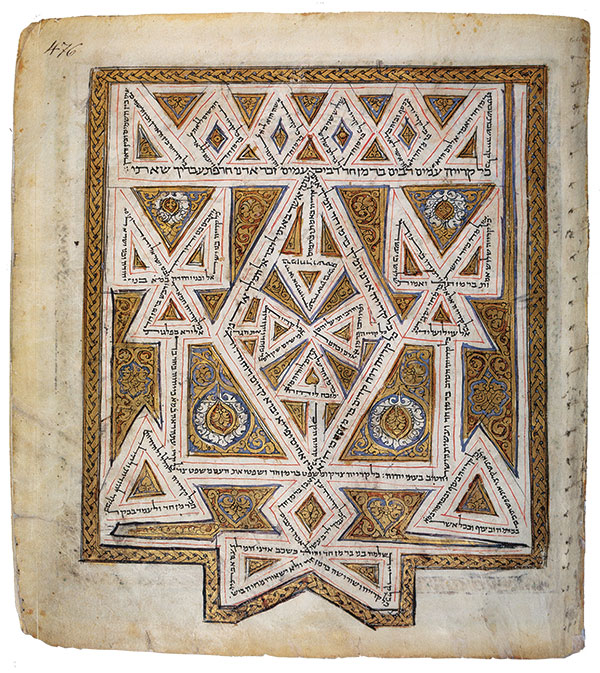

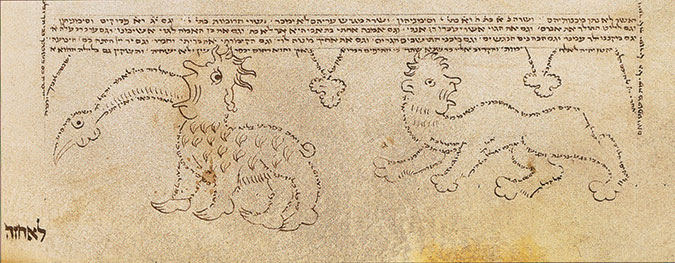

When the manuscript codex was finally adopted by Judaism—the earliest surviving examples date from around the year 1000—it brought with it a new kind of freedom. A Torah scroll could be written only one way, but a Bible—which Jews referred to not by that Greek word, but as mikra, “that which is read aloud,” or “the twenty-four books”—could be annotated, illustrated, and combined with translation or commentary. It was not that Jewish books used unique techniques of production or design. On the contrary, one of Stern’s central arguments is that the Jewish book always reflected the conventions of the Gentile culture in which Jews lived, whether Christian or Islamic. He compares, for instance, the famous Leningrad Codex—the oldest complete Hebrew Bible, produced in Muslim Cairo in 1008—with a Bible produced some two centuries later in Christian Berlin. The former is decorated with “carpet pages,” whose intricate pattern of lines and shapes (and complete lack of representative images) resembles those found in contemporary Qur’ans. The latter, by contrast, features illustrated capitals and marginal drawings of fantastic beasts, of the kind found in Christian illuminated manuscripts.

Yet in both cases, the style is given a decisively Jewish twist through the incorporation of micrography. Look closely at the dragon swallowing a snake in the Berlin Bible, and you will see that the lines are made up of tiny Hebrew letters, as are the lines delineating squares and circles in the Cairo Bible. In both cases, this comprises the text of the Masorah, the annotations developed by Jewish grammarians between the 7th and 11th centuries, which indicate the way the words should be pronounced and chanted—and thereby help to determine the text’s actual meaning.

As Stern shows in a concise introduction to the subject, the Masorah also functioned as an index or concordance, a record of unusual words, and a fence against scribal errors. In standard form, this material was incorporated in the top, bottom, and side margins of the biblical text. But in time, Jewish scribes began to use the text of the Masorah as a design element in and of itself. This transformation of word into image is one of the ways a book could be marked as distinctively Jewish: “Masoretic micrography came to play a prominent role . . . giving expression to that Jewishness.”

When the Jewish Bible entered the age of print, a host of new possibilities emerged. It was difficult for a manuscript to incorporate commentaries, since the scribe would have to estimate in advance the correct proportion of text and annotation on a page. Print technology did away with this obstacle, and the result was the creation in 1517 of the Mikraot gedolot, “the Large Scripture,” also known as the rabbinic Bible. It was followed by an improved edition in 1524, which became the standard Jewish text of the Bible for the next four centuries. Published in Venice by the Christian printer Daniel Bomberg, who recruited converted Jews as editors, each page of the rabbinic Bible featured the original Hebrew, the Aramaic translation or Targum, the Masorah, the commentary of Rashi, and further commentary by Ibn Ezra and others.

Appelbaum, courtesy of the Gross Family Collection.)

It was in this book that the archetypal Jewish page of print—later to be adopted by and associated with the Talmud—first made its appearance. Where early Christian editions of the Bible featured translations running down the page in parallel columns, the Jewish page created a kind of hypertext, with each biblical word keyed to a host of other sources. So influential was this layout that Moses Mendelssohn adopted it for his own translation of the Bible into German, Sefer netivot ha-shalom: Stern reproduces the first page of this book, in which the Targum has been replaced by Mendelssohn’s elegant German (written in Hebrew characters) and the traditional commentaries by Mendelssohn’s own. By contrast, when Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig wanted to produce an ultramodern, 20th-century German Bible, they made their intentions clear by abolishing the crowded traditional page, instead printing the German text in columns that look like free verse.

The big question that looms over the conclusion of The Jewish Bible is whether we are on the verge of another paradigm shift in the way we interact with the sacred text. The changes from scroll to codex and from manuscript to print each changed the way Jews read and thought about the Bible; surely the shift from print to digital will do the same? Surprisingly, however, Stern tends to downplay the significance of the post-Gutenberg age. While the Internet has drastically expanded the reach of scholarship, putting many far-flung editions and texts at the researcher’s fingertips, Stern does not believe it will fundamentally change what we know as the Bible. “[T]he most dramatic transformations that the new technology can effect will,” he argues, “likely be in the study of the Bible rather than in the text itself.”

Stern foresees Jews continuing to read from parchment scrolls, as they surely will. More important, he implies that we will continue to think of the Bible as a book, sequentially divided into chapters and verses. But if a hundred or a thousand years from now books themselves no longer exist except in museums, why would the Bible be an exception? More likely, we can’t even guess at the form that the Bible will take in the consciousness of the future. Maybe Torah will return to its origin as something virtual, text without script—black fire on white fire.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Lost Voices of Salonica

Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s prodigious research, a true labor of love, gives voice to the long-silenced Salonican Jews.

A View from Reservoir Hill

A shul that never left the Old Jewish Neighborhood lives, volunteers, and prays through the recent crisis in Baltimore.

A Failure of Reimagination?

We once worried about the faith of young American Jews; now we worry about their politics. It’s part of a long historical development we should resist because Judaism-as-politics isn’t enough.

Beauty within Beauty: How Lag BaOmer Stopped a Plague

“One cannot, says Hasidism, have to do essentially with God if one does not have to do essentially with men.”

tbrodersen

I think the caption on the illustration of the Berlin Bible is incorrect. According to the text the Berlin Bible is a Jewish Bible produced in Christian Berlin.

ben.donovan

The codex was well suited to the uses of early Christianity because, unlike in a scroll, the reader can stick his finger in the book at one place, quickly compare it to another section, and then flick back. For example, when reading what Jesus has to say about something in the New Testament, you can have a quick glance at Moses' take on the same in the Old, and compare. Hard with a scroll (or several).

gershonhepner

SCROLLS, BOOKS AND HOOKS

In ancient times the holy Torah was a manuscript that Jews would write upon a parchment scroll.

Once printing was invented they divided all its verses and its chapters in an annotated book,

but always their interpretation of the words made their imagination play a greater role

that the printed or handwritten text on which they hung own ideas like an imaginary hook.

[email protected]