Pittsburgh Jews, Squirrel Hill, and the Tree of Life

For weeks after October 27, 2018, the spotlight was on Pittsburgh and its Jewish community. The murder of Joyce Fienberg, Richard Gottfried, Rose Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Cecil Rosenthal, David Rosenthal, Bernice Simon, Sylvan Simon, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax, and Irving Younger during Shabbat morning services at the Tree of Life synagogue by a deranged anti-Semitic gunman was described in horrific detail, and the outpouring of sympathy and solidarity was widely recorded. For many of us who live in Squirrel Hill, have connections to Tree of Life, or know either a victim or their family, our shock and grief in the midst of this frenzy of media attention has been all but overwhelming. But the fact that the deadliest anti-Semitic massacre in American history took place in our city, often rated the “most livable” in the United States, in the heart of its friendliest neighborhood, and in a synagogue historically committed to Christian-Jewish understanding, has made it even harder to absorb the bitter reality. From the impromptu mass vigil organized by local high school students that Saturday night in the heart of Squirrel Hill, at the corner of Forbes and Murray, through the many funerals and memorial services, we have been trying to come to terms with what has happened. One way—perhaps a distinctively Jewish way—of doing so is to tell the thoroughly American story of Jewish Pittsburgh and the Tree of Life to which my friend Joyce Fienberg and the others were so attached.

The first Jews to settle in Pittsburgh came in the 1840s. Most, like William Frank, were itinerant peddlers who had come to America from southern Germany and eventually ended up in Pittsburgh selling dry goods. In 1848, they established the first local synagogue, Shaare Shamayim (Gates of Heaven). Within just a few years, however, there were schisms between the reformers, most of whom were German Jews, and the traditionalists, most of whom were “Polanders.” What had been one synagogue soon became three: a languishing Shaare Shamayim, the Orthodox Beth Israel, and the newly chartered Rodef Shalom (Pursuer of Peace), named, Frank wrote, because they wanted to have peace, which didn’t happen. (As Jonathan Sarna has noted, the proliferation of synagogues putting “Shalom” in their names during this period may have been precisely because there was so little peace within their walls.)

When the leading American Reform rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise visited the community in 1857, he wrote, “As much praise as can be spoken of the social position of our brethren of Pittsburgh, as little can be said of their congregational affairs. . . . The Germans and Poles cannot agree. . . . They meet every Sabbath to read a set of prayers, eat kosher meat and quarrel. That’s all.” Shortly after he returned to Pittsburgh six years later, the majority of German members at Rodef Shalom voted to change the prayer book to his controversial Minhag America, which integrated English readings while eliminating messianic language and the hopes of a restored Temple in Jerusalem. That was the last straw for the traditionalists. In 1864, Gustav Grafner led 15 men to establish a new synagogue they called Ez Hayim, Tree of Life. The name emphasized their commitment to the Torah, to which tradition applies the verse, “It is a tree of life to those who grasp it” (Proverbs 3:18). That fall they hired Isaac Wolf to be the shul’s one all-purpose employee: chazzan, ba’al koreh, shochet, and shamas. In addition to listing leading services, slaughtering animals, collecting money, stoking fires in the stove, and delivering invitations to meetings, the contract stipulated that Wolf was responsible for conducting weddings, arranging for burials, and organizing for the baking and distribution of Passover matza. (Not surprisingly, he left within six months.)

Tree of Life’s first High Holiday service was held in Lafayette Hall at the corner of Fourth and Wood Street, in the same building in which the National Republican Party had first been organized. By the time Rodef Shalom hosted the “Pittsburgh Platform” meetings of the Reform movement two decades later, declaring that that Jewish laws regulating “diet, priestly purity and dress” were now “altogether foreign to our present mental and spiritual state,” Tree of Life had established itself as the spiritual home of moderate traditionalists. When the Jewish Theological Seminary was established shortly thereafter, Tree of Life affiliated with it immediately.

The Civil War had an enormous impact on Pittsburgh. Among the thousands who signed up from Allegheny County, the tiny Pittsburgh Jewish community sent at least 10 young men. When Captain Jacob Brunn was killed at the battle of Williamsburg in 1862, his coffin was draped in an American flag and taken from his father-in-law’s home on Third Avenue to the Jewish cemetery on Troy Hill by a cortege of the city’s “leading citizens without regard to creed or nationality” together with a military escort. The eulogy was described as “at once tender, eloquent, patriotic and just.”

The Civil War also changed Pittsburgh’s economy. Suddenly uniforms, ammunition, cannons, rails, locomotives, and all manner of heavy machinery were needed. Two Jewish firms were tapped by the federal government to help clothe the Union army. By the end of the war, Pittsburgh’s blast furnaces were producing two-fifths of the nation’s iron, and Andrew Carnegie’s name was synonymous with the city’s reputation as an industrial powerhouse. Jews were not a part of Carnegie or anyone else’s industrial conglomerate, nor were they involved with Thomas Mellon’s newly established banking empire. However, by the end of the century almost 90 percent of the clothing manufacturing industry in town was owned by Jews, and, just a few years later, four out of the five department stores in downtown Pittsburgh were Jewish owned.

By the turn of the century, the story of Pittsburgh Jewry was a tale of two cities. The German Jewish elite—the merchants, liquor dealers, and professionals—lived in Allegheny City, which was soon to be incorporated into Pittsburgh as its north shore. Meanwhile, Eastern European Jews from the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Romania were pouring into an area known as the Hill, along with communities of Irish, German, Scotch, Italian, Greek, Armenian, Syrian, Lebanese, and Chinese immigrants, and African Americans. It was a veritable “human cauldron,” a crowded ghetto of dilapidated buildings adjacent to downtown.

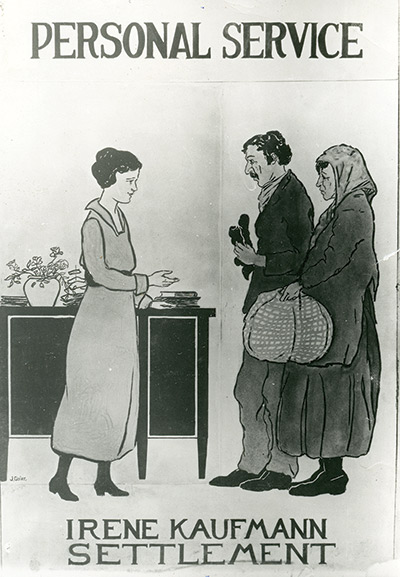

The two Jewish communities were separated not just by distance but by culture, class, and religious and social ideologies. However, despite—or because of—the chasm between them, established German Jews, especially the women, were engaged in efforts to better the lives of the poor immigrants. The Irene Kaufmann Settlement House, heavily financed by Henry Kaufmann, was founded to help the newimmigrants. Kaufmann was one of the brothers who built the famous Kaufmann’s department store in downtown Pittsburgh, which had a replica of the Statue of Liberty perched on top of it, with its torch visible throughout the city.

Frank & Seder, whose owners had come from Russia and who were also leading local philanthropists and members of the Tree of Life congregation, was across the street. When Isaac Seder died in 1924, he left money to Tree of Life, several other Jewish institutions, the Frank & Seder Employees Mutual Benefit Association, and the Home for Colored Children.

The famous muckraker Lincoln Steffens wrote of Pittsburgh in this period that it was not just “Hell with the lid off”—describing the city’s industrial smog and grit—but “Hell with the lid on” because of its graft and corruption. In 1907, the Russell Sage Foundation issued a blistering report, scolding the city’s steel barons for their ruthless business practices and the unconscionable living and working conditions of the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who poured into the city to work in the city’s mills and mines.

Among the leading social reformers responding to these conditions were several Pittsburgh Jews. A. Leo Weil, the head of the Voters League, attacked city corruption; Tree of Life’s Rabbi Rudolph Coffee was nominated by the mayor of Pittsburgh to sit on the Morals Efficiency Commission to combat vice. He was known to go out into the city with local crusader Adolph Edlis and rabbinic colleagues to try to persuade prostitutes to get off the street, often threatening Jewish pimps with excommunication. Bertha Rauh, president of the Pittsburgh chapter of the Council of Jewish Women, served on dozens of boards devoted to improving social conditions. She later became director of public charities, one of the first women to hold office in a mayoral cabinet.

Yet while Jewish leaders such as A. Leo Weil, Rabbi Coffee, Bertha Rauh, and others worked to make local government more responsive to the common ills of society, they remained aware of the anti-Semitism around them. Jews were excluded from the city’s leading social clubs and corporations. And while the upwardly mobile German Jews faced this genteel bigotry, Eastern European Jews felt the more physical kind in their neighborhoods and schools. Ziggy Kahn, the popular athletic director of the Irene Kaufmann Settlement House said that, “The Italian kids were our friends, but the Irish kids on the Hill would accuse the Jews of putting blood in the matzos and we had to fight.”

Nonetheless, in Pittsburgh as elsewhere in America, Jews were integrating and succeeding. Beginning around 1910, Eastern European Jews began to join their more established German Jewish brethren in the nicer East End neighborhoods of Oakland, East Liberty, Bloomfield, and even Squirrel Hill, the most prestigious of them all, with its elegant houses and tree-lined streets. Not that it was easy—when Herman Kamin, a real estate developer, decided to move to Squirrel Hill in 1916, he tried to buy a vacant lot on Darlington near Murray Avenue, but when he approached the agent, he was told that Jews couldn’t buy property in that neighborhood. Kamin ignored the agent, bought the lot under a false name, built himself a house, and then began to buy more property in the area to develop. Squirrel Hill soon became the center of Pittsburgh Jewish life, though Tree of Life would not move from its building in the more modest Oakland neighborhood to its present location in Squirrel Hill until after World War II.

In the 1930s, Pittsburgh, like many cities, had a chapter of the German American Bund spewing its hate direct from Nazi Germany (the head of the Bund actually lived in Squirrel Hill), but the Jewish community and its allies among local Christian leaders fought back. In March 1933, Rabbi Dr. Herman Hailperin of Tree of Life, who had written his doctoral thesis on the use of Rashi’s commentary by medieval Christian scholars, joined his Christian colleagues at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Music Hall to protest the book burnings in Germany. The two thousand participants recited the names of authors whose books had been destroyed in Germany. At the end of the meeting, one hundred local Jewish college students filed past a large table on the platform, each placing on it an English translation of a book destroyed in Hitler’s bonfires.

Around the same time, Ziggy Kahn was organizing an unsuccessful effort to have America boycott the 1936 Olympics games in Berlin. In these years, Rabbi Solomon Freehof of Rodef Shalom, a distinguished rabbinic scholar, was a prime mover in getting Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to bring over as many Jewish refugee scholars as possible, among them the great Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Rabbi Hailperin, who led Tree of Life from 1922 until 1968, was part of the more liberal wing of the Conservative rabbinate. Among the changes he made was to introduce organ music into services (for many years the organist was Ilse Karp, who had arrived from Germany with her husband Richard, a violinist in the Pittsburgh Symphony and later the director of the Pittsburgh Opera). This, together with the elimination of the observance of the second days of Jewish holidays, brought Tree of Life somewhat closer to its erstwhile rival Rodef Shalom, both of which, like American Jewry more generally, thrived in the postwar era.

In 1948, Tree of Life broke ground for its current building in Squirrel Hill, but with the founding of the State of Israel, Rabbi Hailperin called for a stop to the fundraising so the congregation could focus on helping Jews in Israel. The cornerstone of the building, which opened four years later, was hewn from Jerusalem limestone. These were boom years for Tree of Life. In 1959, the synagogue broke ground again to build a new, 1,400-seat sanctuary. A local artist, Nicholas Parrendo, was commissioned to create the massive modernist stained-glass windows which flank its bimah and pews, depicting creation, the acceptance of the Torah, and the Jewish ethos.

Both Tree of Life and the Squirrel Hill community continued to thrive through the 1960s and 1970s. With the collapse of the steel industry in the 1980s, Pittsburgh’s population shrank drastically, with several hundred thousand people leaving town to find work elsewhere. In the process, Pittsburgh became a smaller city, but over time, perhaps, a kinder, gentler one, as well. Industrial jobs had gone, but so too had some of the radical disparities between the haves and have-nots and the mammoth battles between management and workers that punctuated Pittsburgh history. The newer, smaller Pittsburgh was more cohesive, and the Jewish community was a fully integrated part of that new social cohesion.

In 1988, when Mayor Richard Caliguiri suddenly died, City Council President Sophie Masloff became mayor. One year later she ran and won on her own, becoming both the first woman and the first Jew to be elected mayor of Pittsburgh. As the daughter of poor Romanian immigrants who grew up on the Hill, her career and victory marked the acceptance of Jews at all levels of society. One could make a similar claim about Masloff’s contemporary, Myron Cope (Kopelman), who was the color commentator for the Pittsburgh Steelers for 35 years. Both of them had distinctively local, instantly recognizable voices. Cope created the “terrible towel” that continues to be waved enthusiastically by Pittsburgh fans not only for the Steelers games but at Pirates and Penguins games, as well. The extraordinary devotion of Pittsburgh fans to its sports teams is part of the unifying glue of our civic culture.

Although Pittsburgh and its Jewish community have flourished in recent decades, time has been somewhat less kind to Tree of Life. It has been widely remarked that the victims of the shooting ranged in age from 54 to 97. Over the last generation, the demographic of both the synagogue and the Conservative movement has aged and synagogue membership rolls have shrunk. In 2010, Tree of Life merged with Congregation Or L’Simcha. Shortly thereafter Dor Hadash, a Reconstructionist synagogue, began renting space in the building. In 2017, New Light, another Conservative synagogue, sold its building and also began renting space from Tree of Life. Of course, one worries for the continued health of these congregations. On the other hand, their peaceful coexistence is precisely what William Frank and his fellow Pittsburgh Jewish pioneers were aiming for when they named the city’s second synagogue Rodef Shalom.

Unlike Jews of other cities that are, in one way or another, comparable (say, Philadelphia, Chicago, or Cleveland), Pittsburgh’s Jews never moved en masse to the suburbs, and the fact that the community remains centered in Squirrel Hill may have helped with their complete integration into the city’s life. That sense of belonging was clearly in evidence in the hard days that followed. “Stronger Than Hate” signs went up all over town; millions of dollars poured in from young and old, from Christians and Muslims, as well as Jews. The Pittsburgh Steelers came to the funeral of the brothers Cecil and David Rosenthal, who were two of the 11 victims. At their game against the Cleveland Browns, they unveiled a version of the iconic “steelmark” helmet logo of three diamond-shaped stars, replacing the top one with a six-pointed Jewish star. It had been created by local designer Tom Hindes, who lives near the synagogue, on the day of the shooting.

On Tuesday night, November 27, a month after the massacre, I attended the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra’s “Concert for Peace and Unity,” which was organized to honor the Tree of Life synagogue victims and raise money for the six injured Pittsburgh police officers. The incomparable violinist Itzhak Perlman was there, playing themes from Schindler’s List. My husband and I sat next to Officer Dan Mead, who was one of the first responders to arrive on the scene from the local police station. He told us that he had joined the police force in midlife after working as a carpenter (his father had been a policeman), and he insisted he was not a hero; he had been shot while doing his job. When Jeffrey Myers, the dynamic rabbi-cantor of Tree of Life, came up to speak, he showed his civic pride, wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates kippa. The concert ended with the ringing of 11 mournful notes, one for each victim. Our great conductor Manfred Honeck held the silence, his hands raised in the hushed quiet of a packed Heinz Hall.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jewish Pittsburgh in Pictures

There is more to discuss in the coming weeks and months, but today instead of words we offer images.

Digital Anti-Semitism: From Irony to Ideology

From tweeting trolls to digital incitement, a contemporary history.

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

The Devil You Know

Alvin H. Rosenfeld in 2013: “How aggressive this new antisemitism is likely to get and, ultimately, how destructive it will be if it proceeds unchecked are open questions.”

Murray Tucker

You mention Myron Cope, but the first and log time Steelers announcer was Joe Tucker. Joe was a Russian Jew. The owner of the Baseball team's son in law, Bill Benswanger, a German Jew, continually opposed Joe as Pirate's announcer because of his ethnicity. Joe also could not join the German Jewish club in Oakland. Meanwhile, Joe was a close friend of Art Rooney, an Irish Catholic, owner-founder of the Steelers, as well as John H. Harris, another Irish Catholic who owned the local hockey team, the Hornets.

Alan Steinberg

Murray, I remember your father very well. He was an outstanding pro football announcer and used to have a warm up show in 1956 before Pirate games. My grandfather, Archie Steinberg, was the leading kosher butcher for many years, and I believe your father was a customer.

Alan Steinberg

I am now a columnist for InsiderNJ, New Jersey’s leading political website. The following is a link to a column I wrote the night of the tragedy, “My Roots are in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh - And I Can’t Stop Crying.”

https://www.insidernj.com/roots-squirrel-hill-pittsburgh-cant-stop-crying/

It always struck me how linked Squirrel Hill and the Pittsburgh Jewish community was to the world of sports and show business. My grandmother, Rose Steinberg went to eight grade school on the Hill before moving to Squirrel Hill and was a classmate of Oscar Levant. My uncle Alter Steinberg was a graduate of Taylor Allderdice High School and was a close friend of Mort Halpern, who later became famous to viewers of the Ed Sullivan show as Marty Allen of the comedy team, Allen and Rossi. My aunt, Sylka Steinberg Singer learned dancing in preparation for the Kremess. show at Beth Shalom Synagogue from Gene Kelly! My Squirrel Hill memories are with me every day of my life.