Letters, Fall 2013

Superpowered Thinking

As always, Mr. Laqueur’s considerable erudition is very welcome. (“From Russia with Complications,” Summer 2013) I fear that the phenomenon he points to—of Russian immigrants’ bringing a “superpower” mentality to bear on the small country where they now live—might mesh all too well with a parallel Israeli tendency on both the Right and the (increasingly eclipsed) Left. I speak of the mindset that Israeli actions alone can determine the future of the country. On the Right, this means the idea that the settlers can behave however they want, in complete defiance of U.S. and world opinion; on the Left, this means a belief that a “land for peace” deal is the only thing holding back a utopian peace.

Martin Berman-Gorvine via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Kant’s Dignity

Alan Mittleman’s review of the books by Michael Rosen and George Kateb on the topic of dignity (“Two or Three Concepts of Dignity,” Summer 2013) effectively distills the historical and speculative aspects of their respective approaches to the topic in ways that make clear the limits of each work, not only individually and in comparison with each other, but also vis-à-vis the interests of the philosophically attuned Jewish thinker.

Mittleman’s attempt, however, to suggest some-thing of the Kantian character of Rosen’s “argument for respecting the dignity of the remains of deceased persons” badly misfires. He points out that according to Rosen “one would injure one’s own dignity by acting in ways that fail to express respect” for the dead. This is “reminiscent,” opines Mittleman, “of Kant’s infamous view that it is impermissible to tell a lie, even if it would save someone’s life.” True enough, when it comes to human dignity Kant holds no brief for mendacity: “By a lie,” declares Kant in “The Doctrine of Virtue” (1797), “a human being throws away and, as it were, annihilates his dignity as a human being.” However, about the time of the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Georg Ludwig Collins, an auditor in Kant’s course on moral philosophy, recorded the following: “If everyone were well disposed, it would not only be a duty not to lie, but nobody would need to do it . . . however, since men are malicious, it is true that we often court danger by punctilious observance of the truth, and hence has arisen the concept of the necessary lie . . . So far as I am constrained, by force used against me, . . . and I am unable to save myself by silence, the lie is a weapon of defense.” Relative to Mittleman’s remark that a “corpse as such no longer has dignity,” a properly Kantian gloss would be that treating human remains with respect is a duty not to the dead, but with regard to the dead. Kant would classify this as an “indirect” duty to oneself, the fulfillment of which contributes to preserving the dignity of humanity in one’s person.

Phillip Stambovsky, New Haven, CT

Alan Mittleman Responds:

I thank Phillip Stambovsky for his comment on my review. I was not aware of the reminiscence of Collins that he cites. I find it rather shocking in light of Kant’s mature and well-known opinion about lying. When I referred to Kant’s difficult view that lying is under all circumstances impermissible I had in mind his article “On the Supposed Right to Lie from Benevolent Motives.” Kant argues there for an extremely rigorous, exceptionless duty of truth telling. He does not base his argument on another person’s right to the truth but rather on an unconditional duty as an end in itself. (He does, somewhat inconsistently however, invoke the consequences of lying, however well intended or exigent under the circumstances. For him, the consequences are a weakening of what we would today call social trust. He foresees the destruction of the whole moral and judicial underpinning of society.) Kant suggests another reason for the ban on lying, however. He says that while no one has a right to the truth—he thinks that is a meaningless claim—each of us has a “right to his own truthfulness (veracitas).” I took that to imply that we disfigure ourselves when we lie; being untrue to others means being untrue to ourselves. We diminish ourselves thereby. That seemed to me close to Rosen’s view that we would impair our own dignity by the malign treatment of a corpse, even if the cadaver’s “rights” (or the cadaver) suffer no harm.

Proust’s Jewish Melodies

I was enriched by Adam Kirsch’s “Proust Between Halakha and Aggada” (Summer 2013). In the course of his essay, Kirsch quotes a particularly resonant passage of Swann’s Way: “[W]henever I formed a strong attachment to any one of my friends and brought him home . . . my grandfather seldom failed to start humming the ‘O, God of our fathers’ from La Juive, or else ‘Israel, break thy chains,’ . . . I used to be afraid that my friend would recognise it.”

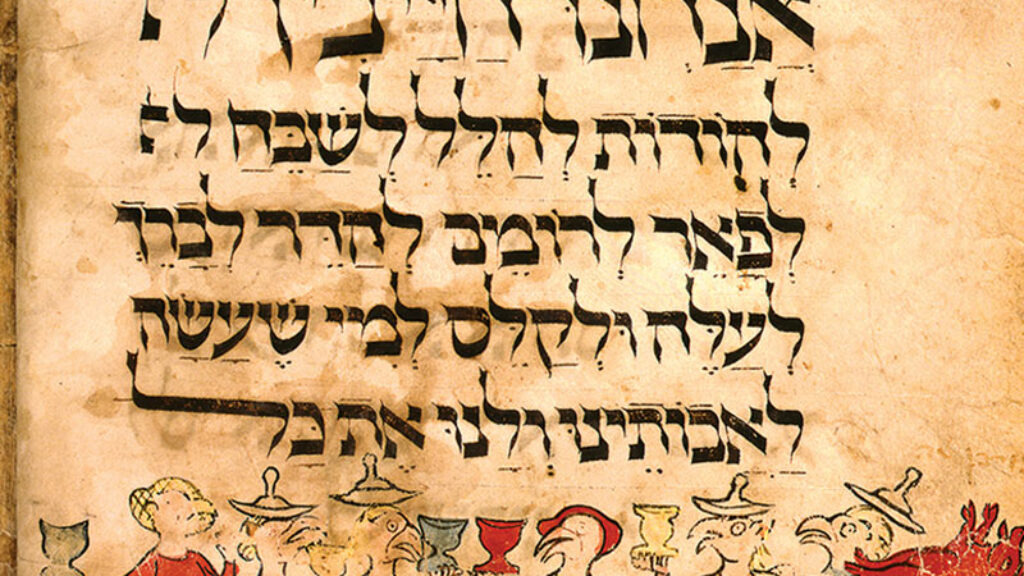

In trying to understand the world of 19th-century Jewry, a great deal is lost in not knowing how mu-sic expressed the interior being of both Jews faith-ful to tradition and those who wished to distance themselves from it. Halévy’s opera La Juive (The Jewess), for instance, was part of the standard repertoire from its inception in the 1830s until the 1930s, when its subject matter became too uncomfortably relevant. When the central character, Eleazar, sings “O Dieu, Dieu de nos peres” (O, God of our fathers) in the Seder scene, the text paraphrases “Shefoch chamatcha el ha-goyim” (Pour out Your wrath upon the nations . . . who have devoured Jacob,” from the haggadah), while seated next to his daughter is a Christian suitor pretending to be a Jew who later becomes justification for a horrible death sentence for his Jewish hosts.

For Jews who left the ghetto to enjoy the bourgeois world outside, opera was a place of fantasy realized. It gave voice to rebellion against oppression. As it happens, in his classic “Culture and Education in the Diaspora,” reprinted in the same issue, Hayim Greenberg writes of the Jew who “cannot carry a part in that choir that gives voice, consciously or not, to what I have called the Jewish melody.” That, I submit, is what the grandfather in Swann’s Way is trying to discover: a response to a melody not “drained of those powers that build a Jewish personality.”

Larry W. Josefovitz, Beachwood, OH

Hayim Greenberg’s Legacy

Back in the late 1970s I spent a year and a half studying at Machon Greenberg, which was then located in the Baka neighborhood of Jerusalem (“Culture and Education in the Diaspora,” Summer, 2013). The school was as a training center for North and South Americans to learn about Jewish history and study Hebrew in order to become teachers either in Israel or in other countries. A fitting salute to the man, I think.

Andrew Tallis via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Suggested Reading

(Almost) People

What does it mean to say that books have lives?

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

Common Clay

Virtually nothing of Babylonian Jewry of the talmudic period, from the 3rd to the 6th century C.E., has survived beyond the Babylonian Talmud itself to help contextualize or confirm the many things the text tells its readers.

Fleishman Is a Series

Fleishman's real problem is not an acrimonious divorce, but an uninspired adaptation.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In