In and Out of Time

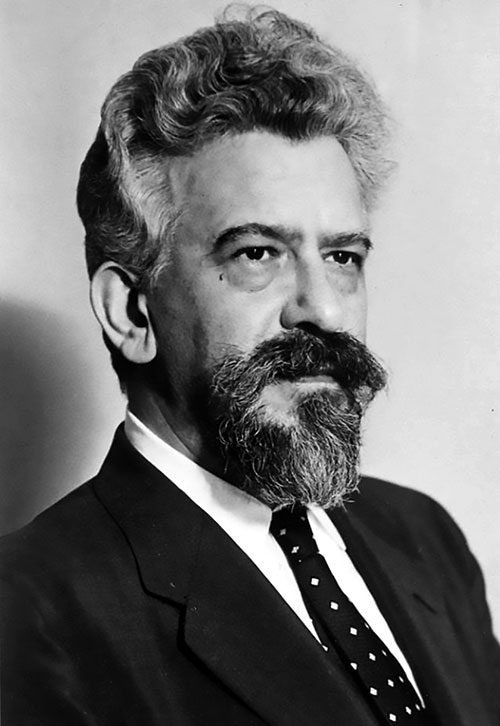

The day after his lecture at the opening in London of the Institute for Jewish Learning, which he had just founded, Abraham Joshua Heschel sent a letter to Julian Morgenstern, the president of the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. It was the end of January 1940. Six months had passed since Heschel had made it to London from Poland, where he had lived since late 1938 when the Nazis forcibly repatriated him. Although he had already received a formal invitation to join the faculty of Hebrew Union College, Heschel could not travel to the United States without the appropriate visa, so he had come to England. He left Poland just a few weeks before the Nazi invasion. Had he waited just a little longer, Heschel might have never seen America, and America might never have known Heschel.

On January 30 he gave the London lecture, the text of which is included In This Hour, an excellent new collection of Heschel’s writings from this period. The lecture challenged his audience to think through with him whether there was a distinctively “Jewish idea of education” and whether it could still be implemented in a modern world now dominated by barbarism. “The duty of Judaism,” he told a somewhat uncomprehending audience, “is to educate Jews to be bearers of that which has been passed down. Being educated means to be bearers of the Spirit.” The following day he penned, in a still-tentative English, the letter to Morgenstern. It began: “I have just obtained the non-quota visa on the strength of my appointment by you. I am very much delighted at the prospect of being soon in Cincinnati. I will lose no time in arranging my journey.” Six weeks later, he was in the United States, a 33-year-old refugee scholar.

As Helen Plotkin comments in her introduction to In This Hour, there is much to be learned from the fact that the moment he arrived in London, which he never intended to be more than a waystation in his flight from Europe, he founded the Institute for Jewish Learning. Heschel did not allow the fact of war or his own uncertain circumstances to get in the way of his commitment to teaching and learning. He lost no time.

Heschel’s life and work can be read through the prism of time or, to use the expression he coined for the title of his monumental work on rabbinic literature, through the aspaklaria, or prism,of the generations. Heschel’s concern with time covers eternity, history, memory, the rhythm of the calendar, the drama of the moment. “Time is the presence of God in the world of space,” he would later write in The Sabbath, “and it is within time that we are able to sense the unity of all beings.”

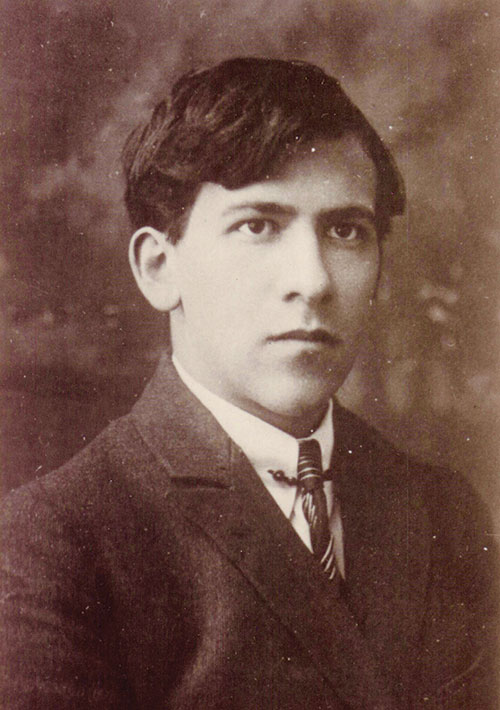

This new collection of writings plucked from obscurity and presented with clarity to English readers adds to our understanding of the centrality of time in Heschel’s worldview. It covers a short and dramatic period in his life. As the book’s introduction explains, Heschel had come to Berlin in 1927 as a young man of 20 who “was always reading either a Hasidic text or a work of philosophy.” Within a decade he had become known as a Jewish teacher and thinker of extraordinary range. While some of the pieces in this work are not dated, they all belong to the period between 1936 and 1941. Up until now, readers of Heschel have known relatively little about these years of uncertainty and upheaval in his life. Now, thanks to the efforts of Susannah Heschel (in whose graceful introduction we learn that Heschel helped his older friend Martin Buber work on his conversational Hebrew before he departed Germany for Jerusalem), Helen Plotkin, and the translators, a new door has been opened.

In This Hour does not, of course, include all of Heschel’s output from his German years. Such a volume would incorporate his Yiddish poetry, his doctoral dissertation on prophecy, a biography of Maimonides, academic articles on medieval philosophy and the meaning of prayer, a speech delivered at a Quaker gathering, a review of a new concordance, and more. Rather, it brings to the attention of the contemporary reader of English some of the least attainable yet most accessible of what Heschel wrote in that period of his life. It is a slight volume, and, as is often the case with Heschel, one must occasionally read between the lines, but it still packs a punch.

In a rare explicit moment, in an essay published before Rosh Hashanah 1936 in the Berlin Jewish community newspaper, the Gemeindeblatt, Heschel rebukes his German Jewish audience.

Some people . . . believed they saw in the year 1933 an awakening to God and the Jewish people, and hoped Jews would be heralds of repentance. Yet we failed, those who stayed here as much as those who emigrated. The enforced Jewishness still sits so loosely in many of us that a new wave of desertions could occur at any moment. The apostasy of the past is matched by the superficiality of today.

Heschel was a philosophically sophisticated modern thinker, but he was unafraid to interpret Hitler’s rise to power as a prompt to teshuvah, a catalyst of repentance. Like the biblical prophets and the rabbinic sages, he read the unfolding of world history as a question posed to the Jewish people. In the 1950s, Heschel was to quote the rabbinic tradition according to which every day a voice issues from Horeb calling us to repent. His sense that Jews failed to awaken in the 1930s was to stay with him into the 1960s, when he saw an opportunity to attempt a more appropriate response. While the conditions in 1960s America were very far removed from Berlin in the 1930s, in both circumstances Heschel strained to hear the call of the hour.

Much of Heschel’s musing on the interplay between the present day and the past is written in coded language. Against the backdrop of Nazi rule, Heschel writes “between the lines.” Take, for example, his eight biographical essays about the early rabbis who also had to cope with tyrannical overlords. They had to choose whether to take the route of unromantic rationalism embodied by Shimon ben Gamliel or resist like Akiva, to unite the people behind a program of reform like Judah ha-Nasi or give in to existential despair like Elisha ben Abuya. These vignettes are not exercises in historiography or hagiography; they echo some of the main subjects of debate among German Jews in the 1930s and constitute what the editor appropriately describes as “spiritual resistance.”

In the 1960s, Heschel was to write his extraordinary Torah min-hashamayim be-aspaklaria ha-dorot (later translated as Heavenly Torah as Refracted through the Generations), which organized and interpreted rabbinic literature using Rabbis Ishmael and Akiva as its two poles. These two sages are presented in that work as embodiments of the tension between the mystical and the rationalistic, other-worldly speculation and this-worldly amelioration, intellectual acrobatics and plausible interpretation. Heschel makes clear that while these two rabbis exemplify that tension, they did not invent it. It predates them, harking back to the biblical period and perhaps embedded in all human endeavor. None of the 1936 essays are devoted to Rabbi Ishmael, but one can see the kernel of that later idea in these early essays, particularly in the portrait of Shimon ben Gamliel. Tellingly, there is already a cautionary aspect to Heschel’s presentation of Rabbi Akiva here: Such genius can be taken to destructive extremes.

In a particularly telling paragraph in his portrait of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, Heschel links that sage with the tradition of the prophets—and takes a swipe at messianic hotheads:

Rabbi Johanan’s attitude and behavior remind us of the great prophetic figures. Like a prophet, he understood how to recognize divine providence in the maze of events. Like Jeremiah in an earlier time, at the last moment, he urged mutual understanding. But—like the orgiastic suggestions of the false prophets in Jeremiah’s time—the national ardor of the Jewish Zealots and the messianic enthusiasts found its way into the hearts of the Jews more easily than Rabbi Johanan’s austere faith. Absolute devotion was easier and more acceptable than insightful acceptance.

It has always been difficult to recognize divine providence in the maze of events, but, Heschel tells us, intellectual moderation and uncompromising morality can at least help to distill the call of the timeless from the rush of actuality.

In the last of the rabbinic portraits, Heschel offers a description of Rabbi Hiyya, in some ways an outlier compared to the other figures profiled. It is hard not to see the link between ancient struggles and contemporary anxieties in these words from the opening paragraph:

The Jews in Palestine—ordinary people as well as scholars—lived in fear that the Torah could be lost to them. They lost their land, their leaders had been killed, and all security was taken from them. Most of them were refugees, emigrants, and martyrs. Their children could not be schooled, and it was almost impossible to maintain the colleges for judges and teachers. Misery hung over them. . . . “The Torah would almost have been forgotten—had Rabbi Hiyya not appeared!”

His readers may have found solace in the notion of a rebuilding of Jewish life after destruction, or they may have noted Hiyya’s strategy of immigration to the Land of Israel as a source of hope. Certainly, these essays represent an act of consolation through history, contemporary comment through deflection, and an affirmation of the Jewish propensity for recovery.

Heschel’s 1937 monograph on the great 15th-century rabbi and diplomat Isaac Abravanel can be read in a similar light. Heschel argues that “[i]n Abravanel a historical view was awakened. He was Judaism’s first humanist” and, even more remarkably, “the true founder of Wissenschaft des Judentums,” the modern, scientific study of Judaism usually associated with the 19th century. But, of course, he was also a leader during perhaps the greatest Jewish crisis before the one through which Heschel and his readers were living, the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews.

When the ancient faith came under . . . heavy attack, disappointment broke the backbone of the faithful. Their disillusionment approached despair. In that hour of crisis, Abravanel wielded his authority, his scholarship, and his faith.

At the very end of the essay, Heschel offers a consoling message so clear that it could hardly have been lost on his readers, facing repatriation, exile, and worse. He notes that the Jews of Spain were expelled from their homeland despite their positions of influence. Had they remained, he notes, they would probably have participated in the acts of the conquistadores, resulting in the decimation of the population of Haiti, among other atrocities. “The desperate Jews of 1492 could not know that a favor had been done them.” Reading these words 80 years after they were penned, it is difficult to see the consolation in this imperfect historical parallel but easy to identify the ethical and pastoral impulses behind it.

It is interesting to note that at the same time as Heschel’s portrait appeared, a book on Abravanel was published by an American Conservative rabbi, Joseph Sarachek. Like Heschel, he wrote the work to mark the 500th anniversary of Abravanel’s birth. Sarachek had no constraint in drawing a direct parallel between the political realities of Abravanel’s day and the current situation. He explicitly wrote what Heschel was obliged to leave implicit.

The claim of a very early settlement in Spain by the Abravanels . . . was frequently made in defense of their right to live in the realm against the acts of persecution and expulsion by their foes. In a similar vein, the German Jews of today dwell upon their one-thousand-year-old residence in their country as a rejoinder to the Nazi pretenses.

As Heschel himself was to discover in America, the art of writing is transformed in the absence of persecution (to borrow the language of Leo Strauss), but he never lost the habit of hinting, offering insights designed to be appreciated by different readers on different levels.

Heschel’s London lecture on Jewish education was written at a moment of considerable uncertainty and at a relatively young age, but, though he would return to the theme toward the end of his life, this may be his most important, inspiring discussion of the topic. “For us, Jewish literature is not a dead past but the immediate present,” Heschel told his audience.

There is something in us that answers when we are seized by the words of our literature. To the Jew, it sometimes seems as if a memory is being awakened in him. The voice of the Spirit speaks from those whose thoughts grow out of a shared memory of Judaism, and our historical experiences are at work in their decisions. . . . Participation in the Jewish spirit is accomplished as recollection.

This is Heschel’s answer as to how one acts in the spirit of Jeremiah and Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai: One must enter into the tradition of Judaism and act and think from its shared memories. This is the task of Jewish education: book-learning that conjures the Spirit and enables collective memory. As Heschel would later often say, adapting a Hasidic thought, “To believe is to remember.”

Heschel’s London audience was not well disposed to his uncompromising insistence that “without a living tradition, as Jews we would go under,” or to his consequent portrayal of Jewish learning as an overtly spiritual act. “My opening lecture, ‘The Idea of Jewish Education’ (which I, myself, think is good!) aroused indignation,” he wrote to Martin Buber, “because I put forth a uniquely Jewish idea of spiritual education.”

Those on the “left” found it “reactionary.” The ignorance and blindness of the people strikes me as the wonder of the century. . . . Others understood its implications.

Heschel’s approach was rooted in tradition, but it wasn’t paralyzed by it. He was a spiritual radical, convinced that only an heir can be a pioneer.

As is inevitable with any work which aims to be both accessible and scholarly, there are some debatable editorial and translation decisions. The endnotes of the Abravanel essay, for example, have been folded into the editor’s comments rather than translated, and some interesting points have been lost. A note appended to the statement that “nothing eternal exists except God” quotes supporting opinions from Saadia Gaon amongst his Jewish predecessors as well as Empedocles and Plato. In the original essay, Heschel goes on to mention the views of Maimonides, Gersonides, and Hermann Cohen. Heschel did not cite contemporary thinkers often, so it is interesting to see him placing Cohen shoulder to shoulder with the greatest philosophers of the Middle Ages.

With regard to translation, I lack both the German and the chutzpahto take systematic issue with translators of the caliber of Stephen Lehmann and Marion Faber; still, there are places where one may quibble. In his biography of Abravanel, Heschel describes his subject’s weakness for messianic speculation, or “calculation of the end.” He then goes on to make a more general comment:

When “the end” is calculated, it isn’t the immediate experience of God, but rather a number, a formula that governs the thinking. What results is not revelation but myth, not direct understanding of God but arid interpretation of Scripture and history.

This is an early example of Heschel’s typological thinking, opposing revelation to myth and direct understanding to arid interpretation. But in the original German, the term for “the immediate experience of God” is das unmittelbare Pathos Gottes. Pathos had already become a central term in his theological vocabulary. The capacity of the prophet to show sympathy for the divine pathos was crucial to Heschel’s understanding of the phenomenon of biblical prophecy, from his German dissertation to his late English work The Prophets. Grasping the pathos of God was never, for Heschel, a purely intellectual act; it was human sympathy with what his interpreter Fritz Rothschild called “the Most Moved Mover.”

Does a book that sheds so much light on Heschel’s life and thought in dark times foreshadow in any way the Heschel who would emerge in later decades? Any expectation that the young Heschel in Nazi Germany would resemble the mature Heschel marching with Dr. King in Alabama is anachronistic. Nonetheless, it strengthens the idea that Heschel’s politico-spiritual action of the 1960s is best understood in the context of these stirrings of spiritual resistance in the 1930s. While the “Never Again!” of many contemporary Jews has become a watchword for vigilant opposition to anti-Semitism, Heschel’s call, no less passionate, was rather never again to leave a space for apathy and disengagement, never again to give in to resignation. As he writes in one of the closing pieces: “Let us not be alone—in this realm of danger, in this time of calamity.”

A remarkable and rare excursion into the realm of fiction pulls the various themes of time—metaphysical, cyclical, spiritual, and immediate—together. In a short piece published in late 1937, Heschel imagines three Jews on a large ocean liner.

They had been thinking about this and that, about what had been and what would be. They were going far away in order to begin a new life. They were going to a country unknown to them. Earlier, in school, they would never have been able to remember the name of this country’s capital.

It is the first night of Hanukkah. The oldest one is more literate in Jewish tradition than his two friends. In the final scene, they light the candles, as “long forgotten days rose from the sea of forgetfulness.” The oldest recites the Shehecheyanu, the “blessing thanking God for letting them live until this time.”

Once long ago, a light burned for eight days when it was supposed to last for only one. Eight days? In eight days we’ll be at our destination, the three of them were thinking. At our destination? We’re only at the beginning.

And then they sang Rock of Ages.

Heschel’s life and work offer constant reflections on the significance of time—the time we sanctify each week in the Sabbath, the times which demand our considered and passionate response, and the time it takes to escape from despair and approach a new destination. We read him now not as an oracle but as part of a living tradition. To recall Heschel in times of exaltation and times of need is to participate in the Jewish spirit.

Suggested Reading

Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

A new batch of Israeli fantasy books may not contain Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

The Wandering Reporter

Read 86 years after it was originally published, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived can be seen as a chilling and prophetic piece of historical reportage.

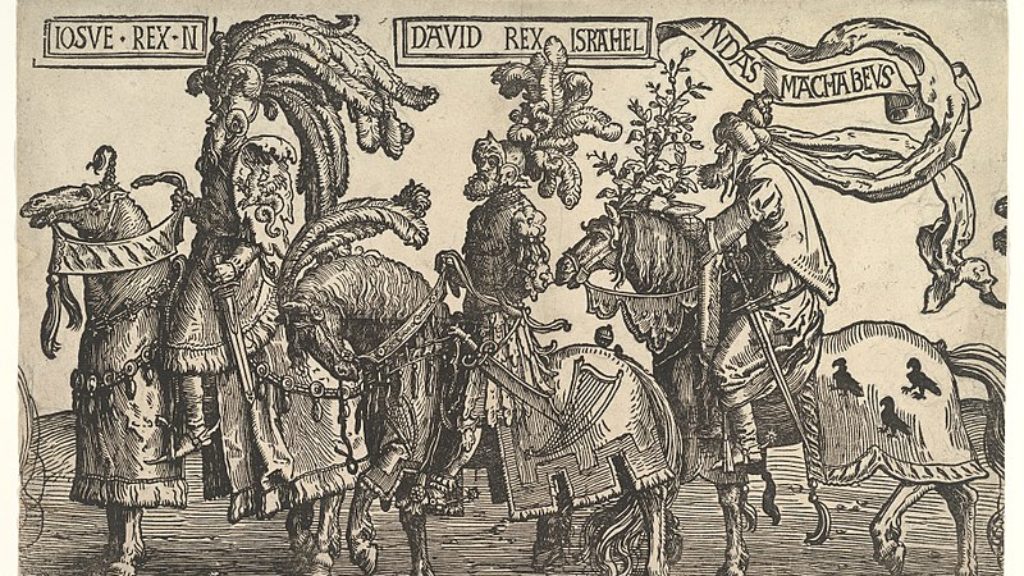

In Memory of Judah Maccabee

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. And were the Maccabees actually underdogs?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In